| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 538 miembros del Colegio Electoral [a] 270 votos electorales necesarios para ganar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apagar | 51,2% [1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

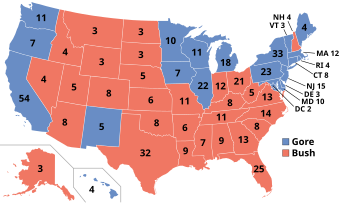

Mapa de resultados de las elecciones presidenciales. El rojo indica los estados ganados por Bush / Cheney y el azul indica los ganados por Gore / Lieberman. Uno de los tres electores de DC se abstuvo de emitir un voto para presidente o vicepresidente. Los números indican los votos electorales emitidos por cada estado y el Distrito de Columbia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

La elección presidencial de 2000 en Estados Unidos fue la 54ª elección presidencial cuadrienal , celebrada el martes 7 de noviembre de 2000. El candidato republicano George W. Bush , gobernador de Texas e hijo mayor del 41º presidente, George HW Bush , ganó la disputada elección. derrotando al candidato demócrata Al Gore , el actual vicepresidente . Fue la cuarta de las cinco elecciones presidenciales estadounidenses, y la primera en 112 años, en la que el candidato ganador perdió el voto popular y es considerada una de las elecciones más reñidas en la historia de Estados Unidos. [2] [3][4] [5]

El titular Bill Clinton no era elegible para un tercer mandato, y Gore se aseguró la nominación demócrata con relativa facilidad, derrotando un desafío del ex senador Bill Bradley . Bush fue visto como el primer favorito para la nominación republicana y, a pesar de una polémica batalla primaria con el senador John McCain y otros, aseguró la nominación para el supermartes . Bush eligió al exsecretario de Defensa Dick Cheney como su compañero de fórmula, mientras que Gore eligió al senador Joe Lieberman .

Los dos candidatos de los principales partidos se centraron principalmente en cuestiones internas, como el presupuesto, la desgravación fiscal y las reformas de los programas federales de seguridad social, aunque la política exterior no fue ignorada. Debido al presidente Bill Clinton 's escándalo sexual con Monica Lewinsky y la posterior destitución , Gore evita hacer campaña con Clinton. Los republicanos denunciaron las indiscreciones de Clinton, mientras que Gore criticó la falta de experiencia de Bush. La noche de las elecciones, no estaba claro quién había ganado, con los votos electorales del estado de Florida aún indecisos. Los resultados mostraron que Bush había ganado Florida por un margen tan estrecho que la ley estatal requería un recuento.. Una serie de un mes de duración de las batallas legales dirigidos a la muy controvertida 5-4 Tribunal Supremo la decisión de Bush v. Gore , que terminó el recuento.

Terminado el recuento, Bush ganó Florida por 537 votos, un margen del 0,009%. El recuento de Florida y el litigio posterior resultaron en una gran controversia postelectoral, y con un análisis especulativo que sugiere que los recuentos limitados basados en el condado probablemente habrían confirmado una victoria de Bush, mientras que un recuento en todo el estado probablemente le habría dado el estado a Gore. [6] [7] En última instancia, Bush ganó 271 votos electorales, un voto más que la mayoría de 270 votos a favor, a pesar de que Gore recibió 543,895 votos más (un margen del 0,52% de todos los votos emitidos). [8] Bush ganó 11 estados que habían votado por los demócratas en las elecciones de 1996 : Arkansas , Arizona , Florida , Kentucky ,Luisiana , Misuri , Nevada , Nueva Hampshire , Ohio , Tennessee y Virginia Occidental .

Antecedentes [ editar ]

El artículo dos de la Constitución de los Estados Unidos dicta que el presidente y el vicepresidente de los Estados Unidos deben ser ciudadanos nativos de los Estados Unidos, tener al menos 35 años de edad y ser residentes de los Estados Unidos por un período de al menos 14 años. Los candidatos a la presidencia generalmente buscan la nominación de uno de los partidos políticos, en cuyo caso cada partido diseña un método (como una elección primaria ) para elegir al candidato que el partido considere más adecuado para postularse para el puesto. Tradicionalmente, las elecciones primarias son elecciones indirectas.donde los votantes votan por una lista de delegados de partido comprometidos con un candidato en particular. Los delegados del partido luego nominan oficialmente a un candidato para que se postule en nombre del partido. Las elecciones generales de noviembre también son elecciones indirectas, en las que los votantes emiten sus votos por una lista de miembros del Colegio Electoral ; estos electores, a su vez, eligen directamente al presidente y al vicepresidente.

El presidente Bill Clinton , demócrata y exgobernador de Arkansas , no era elegible para buscar la reelección para un tercer mandato debido a la Vigésima Segunda Enmienda y, de acuerdo con la Sección 1 de la Vigésima Enmienda , su mandato expiró al mediodía, hora del Este, el 20 de enero. , 2001.

Nominación del Partido Republicano [ editar ]

Esta sección necesita citas adicionales para su verificación . ( mayo de 2020 ) ( Obtenga información sobre cómo y cuándo eliminar este mensaje de plantilla ) |

Boleto del Partido Republicano 2000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| George W. Bush | Dick Cheney | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| para presidente | para vicepresidente | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 46º gobernador de Texas (1995-2000) | XVII Secretario de Defensa de los Estados Unidos (1989-1993) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaña | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Candidatos retirados

| Los candidatos de esta sección se clasifican por voto popular de las primarias. | ||||||

| John McCain | Alan Keyes | Steve Forbes | Gary Bauer | Orrin Hatch | Elizabeth Dole | Pat Buchanan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senador de los Estados Unidos por Arizona (1987-2018) | Asistente Secretario de Estado (1985-1987) | Empresario | Subsecretario de Educación de EE. UU. (1985-1987) | Senador de Estados Unidos por Utah (1977-2019) | Secretario de Trabajo de Estados Unidos (1989-1990) | Director de Comunicaciones de la Casa Blanca (1985-1987) |

| Campaña | Campaña | Campaña | Campaña | Campaña | Campaña | Campaña |

| W: 9 de marzo 6,457,696 votos | W: 25 de julio 1,009,232 votos | W: 10 de febrero151,362 votos | M: 4 de febrero 65,128 votos | W: 26 de enero 20,408 votos | Mi: 20 de octubre 231 votos | Mi: 25 de octubre 0 votos |

Primarias [ editar ]

Bush se convirtió en uno de los primeros candidatos, adquiriendo fondos sin precedentes y una amplia base de apoyo de liderazgo basado en su gobernación de Texas y el reconocimiento del nombre de la familia Bush y sus conexiones en la política estadounidense. El ex miembro del gabinete George Shultz jugó un importante papel temprano en asegurar el apoyo de los republicanos establecidos para Bush. En abril de 1998, invitó a Bush a discutir cuestiones de política con expertos como Michael Boskin , John Taylor y Condoleezza Rice , quien más tarde se convirtió en su secretaria de Estado . El grupo, que estaba "buscando un candidato para el 2000 con buenos instintos políticos, alguien con quien poder trabajar", quedó impresionado y Shultz lo animó a entrar en la contienda. [9]

Varios aspirantes se retiraron ante el Caucus de Iowa porque no obtuvieron fondos y respaldo suficientes para seguir siendo competitivos con Bush. Estos incluyeron a Elizabeth Dole , Dan Quayle , Lamar Alexander y Bob Smith . Pat Buchanan se retiró para postularse para la nominación del Partido Reformista. Eso dejó a Bush, John McCain , Alan Keyes , Steve Forbes , Gary Bauer y Orrin Hatch como los únicos candidatos todavía en la contienda.

El 24 de enero, Bush ganó el caucus de Iowa con el 41% de los votos. Forbes quedó en segundo lugar con el 30% de los votos. Keyes recibió 14%, Bauer 9%, McCain 5% y Hatch 1%. Dos días después, Hatch se retiró y apoyó a Bush. Los medios nacionales retrataron a Bush como el candidato del establishment. McCain, con el apoyo de muchos republicanos e independientes moderados, se presentó como un insurgente cruzado que se centró en la reforma de campaña .

El 1 de febrero, McCain obtuvo una victoria de 49 a 30% sobre Bush en las primarias de New Hampshire . Posteriormente, Bauer se retiró, seguido de Forbes, que quedó tercero en las primarias de Delaware. Esto dejó a tres candidatos. En las primarias de Carolina del Sur , Bush derrotó rotundamente a McCain. Algunos partidarios de McCain acusaron a la campaña de Bush de engaños y trucos sucios, como las encuestas urgentes que implicaban que la hija adoptiva de McCain, nacida en Bangladesh, era una niña afroamericana que engendró fuera del matrimonio. [10] La derrota de McCain en Carolina del Sur dañó su campaña, pero ganó Michigan y su estado natal de Arizona el 22 de febrero.

(Las elecciones primarias de ese año también afectaron a la Casa del Estado de Carolina del Sur , cuando una controversia sobre la bandera confederada que ondeaba sobre la cúpula del capitolio llevó a la legislatura estatal a mover la bandera a una posición menos prominente en un monumento de la Guerra Civil en los terrenos del capitolio . candidatos republicanos dijeron que la cuestión debería dejarse a los votantes de Carolina del Sur, pero McCain se retractó posteriormente y dijo que la bandera debe ser eliminado. [11] )

El 24 de febrero, McCain criticó a Bush por aceptar el respaldo de la Universidad Bob Jones a pesar de su política que prohíbe las citas interraciales . El 28 de febrero, McCain también se refirió a Jerry Falwell y al televangelista Pat Robertson como "agentes de la intolerancia", un término del que se distanció durante su candidatura de 2008 . Perdió Virginia ante Bush el 29 de febrero. El supermartes 7 de marzo, Bush ganó Nueva York, Ohio, Georgia, Missouri, California, Maryland y Maine. McCain ganó Rhode Island, Vermont, Connecticut y Massachusetts, pero se retiró de la carrera. McCain se convirtió en el candidato presidencial republicano 8 años después , pero perdió las elecciones generales anteBarack Obama . El 10 de marzo, Keyes obtuvo el 21% de los votos en Utah. Bush se llevó la mayoría de las contiendas restantes y ganó la nominación republicana el 14 de marzo, ganando su estado natal de Texas y el estado natal de Florida de su hermano Jeb , entre otros. En la Convención Nacional Republicana en Filadelfia, Bush aceptó la nominación.

Bush le pidió al exsecretario de Defensa Dick Cheney que encabezara un equipo para ayudarlo a seleccionar un compañero de fórmula para él, pero finalmente eligió al propio Cheney como candidato a vicepresidente. Si bien la Constitución de los Estados Unidos no prohíbe específicamente a un presidente y un vicepresidente del mismo estado, sí prohíbe a los electores emitir sus votos por personas de su propio estado. En consecuencia, Cheney, que había sido residente de Texas durante casi 10 años, cambió su registro de votante a Wyoming. Si Cheney no hubiera hecho esto, él o Bush habrían perdido sus votos electorales de Texas.

- Totales de delegados

- Gobernador George W. Bush 1526

- Senador John McCain 275

- Embajador Dr. Alan Keyes 23

- El empresario Steve Forbes 10

- Gary Bauer 2

- Ninguno de los nombres mostrados 2

- No comprometido 1

Nominación del Partido Demócrata [ editar ]

Boleto del Partido Demócrata 2000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Al Gore | Joe Lieberman | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| para presidente | para vicepresidente | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 45º Vicepresidente de los Estados Unidos (1993-2001) | Senador estadounidense de Connecticut (1989-2013) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaña | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Candidatos retirados [ editar ]

| Bill Bradley |

|---|

| Senador de Estados Unidos por Nueva Jersey (1979-1997) |

| Campaña |

| W: 9 de marzo 3,027,912 votos |

Principal [ editar ]

Al Gore de Tennessee fue uno de los principales candidatos para la nominación. Otros demócratas prominentes mencionados como posibles contendientes fueron Bob Kerrey , [12] el representante de Missouri Dick Gephardt , el senador de Minnesota Paul Wellstone y el actor y director Warren Beatty . [13] De estos, solo Wellstone formó un comité exploratorio . [14]

Dirigiendo una campaña de insurgencia, Bradley se posicionó como la alternativa a Gore, quien fue miembro fundador del centrista Consejo de Liderazgo Democrático . Mientras que la ex estrella del baloncesto Michael Jordan hizo campaña a su favor en los primeros estados de las primarias, Bradley anunció su intención de hacer campaña "de una manera diferente" realizando una campaña positiva de "grandes ideas". El enfoque de su campaña fue un plan para gastar el superávit presupuestario récord en una variedad de programas de bienestar social para ayudar a los pobres y la clase media, junto con la reforma del financiamiento de campañas y el control de armas .

Gore derrotó fácilmente a Bradley en las primarias, en gran parte debido al apoyo del establecimiento del Partido Demócrata y la mala actuación de Bradley en el caucus de Iowa, donde Gore pintó con éxito a Bradley como distante e indiferente a la difícil situación de los agricultores. Lo más cerca que estuvo Bradley de una victoria fue su derrota por 50-46 ante Gore en las primarias de New Hampshire. El 14 de marzo, Gore consiguió la nominación demócrata.

Ninguno de los delegados de Bradley pudo votar por él, por lo que Gore ganó la nominación por unanimidad en la Convención Nacional Demócrata . El senador de Connecticut , Joe Lieberman, fue nominado para vicepresidente por voto de voz. Lieberman se convirtió en el primer judío estadounidense en ser elegido para este puesto por un partido importante. Gore eligió a Lieberman sobre otros cinco finalistas: los senadores Evan Bayh , John Edwards y John Kerry , el líder de la minoría de la Cámara, Dick Gephardt , y la gobernadora de New Hampshire, Jeanne Shaheen . [15]

Totales de delegados:

- Vicepresidente Albert Gore Jr. 4328

- Abstenciones 9

Otras nominaciones [ editar ]

Nominación del Partido Reformista [ editar ]

| Boleto del Partido de la Reforma 2000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pat Buchanan | Ezola Foster | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| para presidente | para vicepresidente | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Director de Comunicaciones de la Casa Blanca (1985-1987) | Activista político conservador | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaña | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Candidatos del Partido Reformista

- Pat Buchanan de Virginia , ex redactor de discursos y asesor principal del presidente Richard Nixon

- John Hagelin de Iowa , Ph.D., candidato anterior y actual del Partido de la Ley Natural

- Donald Trump de Nueva York , había abandonado el Partido Republicano en 1999 [16] [17] debido a ideas contradictorias sobre temas clave

La nominación fue para Pat Buchanan [18] y su compañera de fórmula Ezola Foster de California a pesar de las objeciones del fundador del partido Ross Perot ya pesar de una nominación de John Hagelin a la convención por parte de la facción Perot. Al final, la Comisión Federal de Elecciones se puso del lado de Buchanan, y ese boleto apareció en 49 de las 51 boletas posibles.

Nominación de la Asociación de Partidos Verdes del Estado [ editar ]

Entrada 2000 de la Asociación de Partidos Verdes del Estado | |

|---|---|

| Ralph Nader | Winona LaDuke |

| para presidente | para vicepresidente |

| Fundador de Public Citizen | Activista de Minnesota |

| Campaña | |

- Candidatos del Partido Verde : [19]

- Ralph Nader de Connecticut - 295

- Jello Biafra de California - 10

- Stephen Gaskin de Tennessee - 11

- Joel Kovel de Nueva York - 3

- Abstenerse - 1

Los Verdes / Partido Verde de EE . UU. , La organización del partido nacional entonces reconocida, más tarde respaldó a Nader para presidente y apareció en las boletas de 43 estados y DC .

Nominación del Partido Libertario [ editar ]

Escritor Harry Browne

de Tennessee

( campaña )Art Olivier

Mayor (1998-1999) de Bellflower, California

( campaña )

- Candidatos del Partido Libertario delegados totales: [20]

- Harry Browne de Tennessee - 493

- Don Gorman de New Hampshire - 166

- Jacob Hornberger de Virginia - 120

- Barry Hess de Arizona - 53

- Ninguno de los anteriores - 23

- otras escrituras - 15

- David Hollist de California - 8

El partido libertario 's Convención Nacional de nominaciones nominada Harry Browne de Tennessee y Arte Olivier desde California para presidente y vicepresidente. Browne fue nominado en la primera votación y Olivier recibió la nominación a vicepresidente en la segunda votación. [21] Browne apareció en todas las votaciones estatales excepto en la de Arizona, debido a una disputa entre el Partido Libertario de Arizona (que en su lugar nominó a L. Neil Smith ) y el Partido Libertario nacional .

Nominación del Partido de la Constitución [ editar ]

- Candidatos del Partido de la Constitución :

- Howard Phillips

- Hierba Titus

- Mathew Zupan

- Bob Smith Senador de los Estados Unidos por New Hampshire (1990-2003)

Miembro de la Cámara de Representantes de los Estados Unidos por el NH-01 (1985-1990) Retiro: 17 de agosto de 1999

El Partido de la Constitución nominó a Howard Phillips de Virginia por tercera vez y a Curtis Frazier de Missouri . Estaba en la boleta electoral en 41 estados. [22]

Nominación del Partido de la Ley Natural [ editar ]

- John Hagelin de Iowa y Nat Goldhaber de California

El Partido de la Ley Natural celebró su convención nacional en Arlington, Virginia , del 31 de agosto al 2 de septiembre, nominando por unanimidad una candidatura de Hagelin / Goldhaber sin votación nominal. [23] El partido estaba en 38 de las 51 votaciones a nivel nacional. [22]

Independientes [ editar ]

- Bob Smith Senador de los Estados Unidos por New Hampshire (1990-2003)

Miembro de la Cámara de Representantes de los Estados Unidos por el NH-01 (1985-1990) Retiro: 28 de octubre de 1999

Campaña de elecciones generales [ editar ]

Aunque la campaña se centró principalmente en cuestiones internas, como el superávit presupuestario proyectado, las reformas propuestas de la Seguridad Social y Medicare , la atención médica y los planes en competencia para la desgravación fiscal, la política exterior fue a menudo un problema.

Bush criticó las políticas de la administración Clinton en Somalia , donde 18 estadounidenses murieron en 1993 tratando de resolver las facciones en guerra, y en los Balcanes, donde las tropas de mantenimiento de la paz de Estados Unidos desempeñan una variedad de funciones. "No creo que nuestras tropas deban usarse para lo que se llama construcción nacional ", dijo Bush en el segundo debate presidencial . [24] Bush también se comprometió a cerrar las brechas partidistas, afirmando que la atmósfera en Washington se interponía en el camino del progreso de las reformas necesarias. [25] Mientras tanto, Gore cuestionó la idoneidad de Bush para el puesto, señalando los errores cometidos por Bush en entrevistas y discursos y sugiriendo que carecía de la experiencia necesaria para ser presidente.

El juicio político de Bill Clinton y el escándalo sexual que lo condujo arrojaron una sombra sobre la campaña. Los republicanos denunciaron enérgicamente los escándalos de Clinton y Bush prometió restaurar el "honor y la dignidad" de la Casa Blanca como pieza central de su campaña. Gore evitó cuidadosamente los escándalos de Clinton, al igual que Lieberman, a pesar de que Lieberman había sido el primer senador demócrata en denunciar la mala conducta de Clinton. Algunos observadores teorizaron que Gore eligió a Lieberman en un intento de separarse de las fechorías pasadas de Clinton y ayudar a mitigar los intentos del Partido Republicano de vincularlo con su jefe. [26] Otros señalaron el beso apasionado que Gore le dio a su esposa durante la Convención Demócrata.como señal de que, a pesar de las acusaciones contra Clinton, el propio Gore era un marido fiel. [27] Gore evitó aparecer con Clinton, quien fue desviado a apariciones de poca visibilidad en áreas donde era popular. Los expertos han argumentado que esto podría haber costado los votos de Gore a algunos de los principales partidarios de Clinton. [28] [29]

Ralph Nader fue el más exitoso de los candidatos de terceros. Su campaña estuvo marcada por una gira itinerante de grandes "súper rallyes" que se llevaron a cabo en estadios deportivos como el Madison Square Garden , con el presentador retirado de programas de entrevistas Phil Donahue como maestro de ceremonias. [30] Después de ignorar inicialmente a Nader, la campaña de Gore hizo un lanzamiento a los posibles partidarios de Nader en las últimas semanas de la campaña, [31] minimizando sus diferencias con Nader en los temas y argumentando que las ideas de Gore eran más similares a las de Nader que las de Bush y que Gore tenía más posibilidades de ganar que Nader. [32] Por otro lado, el Consejo de Liderazgo Republicanopublicó anuncios pro-Nader en algunos estados en un esfuerzo por dividir el voto liberal. [33] Nader dijo que el objetivo de su campaña era pasar el umbral del 5 por ciento para que su Partido Verde fuera elegible para fondos de contrapartida en futuras carreras. [34]

Los candidatos a la vicepresidencia, Cheney y Lieberman, hicieron una campaña agresiva. Ambos campamentos hicieron numerosas paradas de campaña en todo el país, a menudo simplemente perdiéndose entre sí, como cuando Cheney, Hadassah Lieberman y Tipper Gore asistieron al Taste of Polonia de Chicago durante el fin de semana del Día del Trabajo . [35]

Debates presidenciales [ editar ]

| No. | Fecha | Anfitrión | Ciudad | Moderador | Participantes | Audiencia (millones) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Martes, 3 de octubre de 2000 | Universidad de Massachusetts Boston | Boston, Massachusetts | Jim Lehrer | Gobernador George W. Bush Vicepresidente Al Gore | 46,6 [36] |

| Vicepresidente | Jueves, 5 de octubre de 2000 | Centro universitario | Danville, Kentucky | Bernard Shaw | Secretario Dick Cheney Senador Joe Lieberman | 28,5 [36] |

| P2 | Miércoles, 11 de octubre de 2000 | Universidad Wake Forest | Winston-Salem, Carolina del Norte | Jim Lehrer | Gobernador George W. Bush Vicepresidente Al Gore | 37,5 [36] |

| P3 | Martes 17 de octubre de 2000 | Universidad de Washington en St. Louis | San Luis, Misuri | Jim Lehrer | Gobernador George W. Bush Vicepresidente Al Gore | 37,7 [36] |

Boston, MA

Danville, KY

St. Louis, MO

Winston-Salem, Carolina del Norte

Después de las elecciones presidenciales de 1996 , la Comisión de Debates Presidenciales estableció nuevos criterios de selección de candidatos. [41] Los nuevos criterios requerían que los candidatos de terceros partidos votaran al menos el 15% de los votos en las encuestas nacionales para poder participar en los debates presidenciales patrocinados por el CPD. [41] A Nader se le impidió asistir a una proyección de circuito cerrado del primer debate a pesar de tener un boleto, [42] y se le prohibió asistir a una entrevista cerca del sitio del tercer debate ( Universidad de Washington en St. Louis ) a pesar de tener un " paso perimetral ". [43]Más tarde, Nader demandó al CPD por su papel en el incidente anterior. Se llegó a un acuerdo que incluía una disculpa. [44]

Expresiones y frases notables [ editar ]

- Fondo Lockbox / Rainy Day: descripción de Gore de lo que haría con el superávit del presupuesto federal.

- Matemáticas difusas : término utilizado por Bush para descartar las cifras utilizadas por Gore. Otros luego volvieron el término en contra de Bush. [45] [46]

- Al Gore inventó Internet : una interpretación de Gore que dijo que "tomó la iniciativa en la creación de Internet", lo que significa que estaba en el comité que financió la investigación que condujo a la formación de Internet.

- " Strategery ": una frase pronunciada por Saturday Night Live ' carácter s Bush (interpretado por Will Ferrell ), que Bush escogió empleados en broma hasta describir sus operaciones.

Resultados [ editar ]

Esta sección no cita ninguna fuente . ( Junio de 2020 ) ( Obtenga información sobre cómo y cuándo eliminar este mensaje de plantilla ) |

Con las excepciones de Florida y Tennessee , el estado natal de Gore , Bush llevó a los estados del sur por márgenes cómodos (incluido el estado natal de Clinton de Arkansas) y también ganó Ohio , Indiana , la mayoría de los estados agrícolas rurales del Medio Oeste , la mayoría de los estados de las Montañas Rocosas, y Alaska. Gore equilibró a Bush barriendo el noreste de Estados Unidos (con la excepción de New Hampshire , que Bush ganó por un estrecho margen), los estados de la costa del Pacífico, Hawai , Nuevo México y la mayor parte del Medio Oeste Superior .

A medida que avanzaba la noche, los resultados en un puñado de estados pequeños a medianos, incluidos Wisconsin , Iowa , Oregón y Nuevo México (Gore por 355 votos) fueron extremadamente cercanos, pero la elección se redujo a Florida. Cuando se contabilizaron los resultados nacionales finales a la mañana siguiente, Bush claramente había ganado 246 votos electorales y Gore 250, con 270 necesarios para ganar. Dos estados más pequeños, Wisconsin (11 votos electorales) y Oregón (7), estaban todavía demasiado cerca para ser convocados, pero los 25 votos electorales de Florida serían decisivos independientemente de sus resultados. El resultado de la elección no se conoció durante más de un mes después de que finalizó la votación debido al tiempo requerido para contar y volver a contar las boletas de Florida.

Recuento de Florida [ editar ]

Entre las 7:50 pm y las 8:00 pm EST del 7 de noviembre, justo antes de que cerraran las urnas en el territorio mayoritariamente republicano de Florida, que se encuentra en la zona horaria central, todas las principales cadenas de noticias de televisión (CNN, NBC, FOX, CBS y ABC) declaró que Gore había ganado Florida. Basaron esta predicción sustancialmente en encuestas a boca de urna.. Pero en el recuento de votos, Bush comenzó a tomar una amplia ventaja a principios de Florida, y para las 10 pm EST, las cadenas se habían retractado de sus predicciones y habían vuelto a colocar a Florida en la columna de "indecisos". Aproximadamente a las 2:30 am del 8 de noviembre, con el 85% de los votos contados en Florida y Bush a la cabeza de Gore por más de 100.000 votos, las redes declararon que Bush había ganado Florida y por lo tanto había sido elegido presidente. Pero la mayoría de los votos restantes que se contarán en Florida fueron en tres condados fuertemente demócratas: Broward , Miami-Dade y Palm Beach.—Y cuando se informaron sus votos, Gore comenzó a ganarle a Bush. A las 4:30 am, después de que se contaron todos los votos, Gore había reducido el margen de Bush a menos de 2.000 votos, y las cadenas se retractaron de sus declaraciones de que Bush había ganado Florida y la presidencia. Gore, que había concedido en privado la elección a Bush, retiró su concesión . El resultado final en Florida fue lo suficientemente pequeño como para requerir un recuento obligatorio (por máquina) según la ley estatal; La ventaja de Bush se redujo a poco más de 300 votos cuando se completó el día después de las elecciones. El 8 de noviembre, el personal de la División de Elecciones de Florida preparó un comunicado de prensa para la Secretaria de Estado de Florida, Katherine Harris, que decía que las boletas de votación en el extranjero deben tener "matasellos o firma y fecha" antes del día de las elecciones. Nunca fue lanzado. [7]: 16 Un recuento de los votos en el extranjero aumentó posteriormente el margen de Bush a 930 votos. (Según un informe de The New York Times , 680 de las papeletas de votación aceptadas en el extranjero se recibieron después de la fecha límite legal, carecían de matasellos obligatorios o de la firma o dirección de un testigo, o estaban sin firmar o sin fecha, emitidas después del día de las elecciones, de votantes no registrados o de votantes no solicitar papeletas o contar dos veces. [47] )

La mayor parte de la controversia postelectoral giró en torno a la solicitud de Gore de contar a mano en cuatro condados (Broward, Miami-Dade, Palm Beach y Volusia ), según lo dispuesto en la ley estatal de Florida. Harris, quien también copresidió la campaña de Bush en Florida, anunció que rechazaría los totales revisados de esos condados si no se entregaban antes de las 5 pm del 14 de noviembre, la fecha límite legal para las declaraciones enmendadas. La Corte Suprema de Florida extendió el plazo hasta el 26 de noviembre, decisión que luego fue anulada por la Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos.. Miami-Dade finalmente detuvo su recuento y volvió a presentar su total original a la junta de escrutinio estatal, mientras que el condado de Palm Beach no cumplió con la fecha límite extendida, entregando sus resultados completos del recuento a las 7 pm, que Harris rechazó. El 26 de noviembre, la junta de escrutinio estatal certificó a Bush como el ganador de los electores de Florida por 537 votos. Gore impugnó formalmente los resultados certificados. Una decisión de un tribunal estatal que anulaba a Gore fue revocada por la Corte Suprema de Florida, que ordenó un recuento de más de 70,000 boletas previamente rechazadas como votos insuficientes por los contadores de máquinas. La Corte Suprema de Estados Unidos detuvo esa orden al día siguiente, y el juez Scalia emitió una opinión concurrente de que "el recuento de votos que son de legalidad cuestionable, en mi opinión, amenaza con un daño irreparable al peticionario" (Bush).[48]

El 12 de diciembre, la Corte Suprema dictaminó en una decisión per curiam (afirmada como un voto de 7 a 2) que la decisión de la Corte Suprema de Florida que requería un recuento de las boletas en todo el estado era inconstitucional por motivos de protección igual, y en un voto de 5 a 4 se revocó y devolvió el caso a la Corte Suprema de Florida para su modificación antes de la fecha límite opcional de "puerto seguro", que la Corte Suprema argumentó que la corte de Florida había dicho que el estado tenía la intención de cumplir. Con solo dos horas para la fecha límite del 12 de diciembre, la orden de la Corte Suprema puso fin al recuento y se mantuvo el total certificado previamente.

Incluso si la Corte Suprema había decidido de manera diferente en Bush v. Gore , la Legislatura de Florida se había estado reuniendo en Sesión Especial desde el 8 de diciembre con el propósito de seleccionar una lista de electores el 12 de diciembre en caso de que la disputa aún continuara. [49] [50] Si el recuento se hubiera adelantado, habría otorgado esos electores a Bush, basándose en el voto certificado por el estado, y el último recurso probable de Gore habría sido disputar a los electores en el Congreso de los Estados Unidos. Entonces, los electores habrían sido rechazados solo si ambas cámaras estuvieran de acuerdo en hacerlo. [51]

Resultados nacionales [ editar ]

Aunque Gore quedó en segundo lugar en la votación electoral, recibió 547.398 votos más populares que Bush, [52] convirtiéndolo en la primera persona desde Grover Cleveland en 1888 en ganar el voto popular pero perder en el Colegio Electoral. [53] Gore no logró ganar el voto popular en su estado natal, Tennessee , que tanto él como su padre habían representado en el Senado, convirtiéndolo en el primer candidato presidencial de un partido importante en perder su estado natal desde que George McGovern perdió Dakota del Sur. en 1972 . Además, Gore perdió West Virginia , un estado que había votado a los republicanos solo una vez en las seis elecciones presidenciales anteriores,[54] y Arkansas , que había votado dos veces antes para elegir vicepresidente de Gore. Una victoria en cualquiera de estos tres estados (o cualquier estado que ganó Bush) le habría dado a Gore suficientes votos electorales para ganar la presidencia.

Antes de la elección, se había advertido la posibilidad de que diferentes candidatos obtuvieran el voto popular y el Colegio Electoral, pero generalmente con la expectativa de que Gore ganara el Colegio Electoral y Bush el voto popular. [55] [56] [57] [58] [59] La idea de que Bush pudiera ganar el Colegio Electoral y Gore el voto popular no se consideró probable.

Esta fue la primera vez desde 1928 en la que un candidato republicano no titular ganó Virginia Occidental.

Los resultados del Colegio Electoral fueron los más cercanos desde 1876 . Los 266 votos electorales de Gore son los más altos para un candidato perdedor.

Bush fue el primer republicano en la historia de Estados Unidos en ganar la presidencia sin ganar Vermont o Illinois, el segundo republicano en ganar la presidencia sin ganar California ( James A. Garfield en 1880 fue el primero) o Pensilvania ( Richard Nixon en 1968 fue el primero) y el primer republicano ganador que no recibió ningún voto electoral de California (Garfield recibió un voto en 1880). Bush también perdió en Connecticut, el estado de su nacimiento. A partir de 2021, Bush es el último candidato republicano en ganar New Hampshire.

Esta fue la primera vez desde que Iowa ingresó a la unión en 1846 en la que el estado votó por un candidato presidencial demócrata en cuatro elecciones seguidas (1988, 1992, 1996 y 2000), y la última vez hasta 2020 que Iowa no votó. para el ganador general. Había dos condados en la nación que habían votado a los republicanos en 1996 y a los demócratas en 2000: el condado de Charles, Maryland y el condado de Orange, Florida , ambos condados que se diversifican rápidamente. Las elecciones de 2000 también fueron la última vez que un republicano ganó una serie de condados urbanos populosos que desde entonces se han convertido en bastiones demócratas. Estos incluyen el condado de Mecklenburg, Carolina del Norte (Charlotte); Condado de Marion, Indiana (Indianápolis),El condado de Fairfax, Virginia (suburbios de DC) y el condado de Travis, Texas (Austin). En 2016 , el republicano Donald Trump perdió Mecklenburg en un 30%, Marion en un 23%, Fairfax en un 36% y Travis en un 38%. Por el contrario, a partir de 2021, Gore es el último demócrata que ha ganado algún condado en Oklahoma. [60]

| Candidato presidencial | Fiesta | Estado natal | Voto popular | Voto electoral | Compañero de carrera | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contar | Porcentaje | Candidato a la vicepresidencia | Estado natal | Voto electoral | ||||

| George Walker Bush | Republicano | Texas | 50,456,002 | 47,86% | 271 | Richard Bruce Cheney | Wyoming | 271 |

| Albert Arnold Gore, Jr. | Democrático | Tennesse | 50,999,897 | 48,38% | 266 | Joseph Isadore Lieberman | Connecticut | 266 |

| Ralph Nader | Verde | Connecticut | 2,882,955 | 2,74% | 0 | Winona LaDuke | Minnesota | 0 |

| Pat Buchanan | Reforma | Virginia | 448,895 | 0,43% | 0 | Ezola B. Foster | California | 0 |

| Harry Browne | Libertario | Tennesse | 384,431 | 0,36% | 0 | Arte Olivier | California | 0 |

| Howard Phillips | Constitución | Virginia | 98,020 | 0,09% | 0 | Curtis Frazier | Misuri | 0 |

| John Hagelin | La Ley natural | Iowa | 83,714 | 0,08% | 0 | Nat Goldhaber | California | 0 |

| Otro | 51.186 | 0,05% | - | Otro | - | |||

| ( abstención ) [c] | - | - | - | - | 1 | (abstención) [c] | - | 1 |

| Total | 105,421,423 | 100% | 538 | 538 | ||||

| Necesitaba ganar | 270 | 270 | ||||||

- Fuente: "Voto Popular y Electoral Presidencial 2000" (Excel 4.0) . Comisión Federal de Elecciones.

Resultados por condado, sombreados según el porcentaje de votos del candidato ganador.

Participación de votos por condado para el candidato del Partido Verde Ralph Nader. Los tonos más oscuros indican un rendimiento verde más fuerte.

Resultados de las elecciones por condado.

Resultados de las elecciones por distrito del Congreso.

Resultados por estado [ editar ]

| Estados / distritos ganados por Gore / Lieberman | |

| Estados / distritos ganados por Bush / Cheney | |

| † | Resultados generales (para estados que dividen los votos electorales) |

Republicano de George W. Bush | Demócrata de Al Gore | Ralph Nader Verde | Reforma de Pat Buchanan | Harry Browne Libertario | Constitución de Howard Phillips | Ley natural de John Hagelin | Otros | Margen | Total del estado | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expresar | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | EV | # | % | # | |

| Alabama | 9 | 941,173 | 56,48% | 9 | 692,611 | 41,57% | - | 18,323 | 1,10% | - | 6.351 | 0,38% | - | 5.893 | 0,35% | - | 775 | 0,05% | - | 447 | 0,03% | - | 699 | 0,04% | - | 248,562 | 14,92% | 1,666,272 | Alabama |

| Alaska | 3 | 167,398 | 58,62% | 3 | 79,004 | 27,67% | - | 28,747 | 10,07% | - | 5.192 | 1,82% | - | 2.636 | 0,92% | - | 596 | 0,21% | - | 919 | 0,32% | - | 1.068 | 0,37% | - | 88,394 | 30,95% | 285,560 | Alaska |

| Arizona * | 8 | 781.652 | 51,02% | 8 | 685,341 | 44,73% | - | 45,645 | 2,98% | - | 12,373 | 0,81% | - | - | - | - | 110 | 0,01% | - | 1,120 | 0,07% | - | 5.775 | 0,38% | - | 96,311 | 6,29% | 1,532,016 | Arizona |

| Arkansas | 6 | 472,940 | 51,31% | 6 | 422,768 | 45,86% | - | 13,421 | 1,46% | - | 7.358 | 0,80% | - | 2,781 | 0,30% | - | 1.415 | 0,15% | - | 1.098 | 0,12% | - | - | - | - | 50,172 | 5,44% | 921,781 | Arkansas |

| California | 54 | 4,567,429 | 41,65% | - | 5.861.203 | 53,45% | 54 | 418,707 | 3,82% | - | 44,987 | 0,41% | - | 45.520 | 0,42% | - | 17.042 | 0,16% | - | 10,934 | 0,10% | - | 34 | 0,00% | - | −1,293,774 | −11,80% | 10,965,856 | California |

| Colorado | 8 | 883,748 | 50,75% | 8 | 738,227 | 42,39% | - | 91,434 | 5,25% | - | 10,465 | 0,60% | - | 12,799 | 0,73% | - | 1.319 | 0,08% | - | 2,240 | 0,13% | - | 1,136 | 0,07% | - | 145,521 | 8,36% | 1,741,368 | CO |

| Connecticut | 8 | 561,094 | 38,44% | - | 816.015 | 55,91% | 8 | 64,452 | 4,42% | - | 4.731 | 0,32% | - | 3,484 | 0,24% | - | 9,695 | 0,66% | - | 40 | 0,00% | - | 14 | 0,00% | - | −254,921 | −17,47% | 1,459,525 | Connecticut |

| Delaware | 3 | 137,288 | 41,90% | - | 180.068 | 54,96% | 3 | 8,307 | 2,54% | - | 777 | 0,24% | - | 774 | 0,24% | - | 208 | 0,06% | - | 107 | 0,03% | - | 93 | 0,03% | - | −42,780 | −13,06% | 327,622 | Delaware |

| corriente continua | 3 | 18.073 | 8,95% | - | 171,923 | 85,16% | 3 | 10,576 | 5,24% | - | - | - | - | 669 | 0,33% | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 653 | 0,32% | 1 | −153,850 | −76,20% | 201,894 | corriente continua |

| Florida | 25 | 2,912,790 | 48,85% | 25 | 2,912,253 | 48,84% | - | 97.488 | 1,63% | - | 17.484 | 0,29% | - | 16,415 | 0,28% | - | 1,371 | 0,02% | - | 2,281 | 0,04% | - | 3,028 | 0,05% | - | 537 | 0,01% | 5.963.110 | Florida |

| Georgia | 13 | 1.419.720 | 54,67% | 13 | 1,116,230 | 42,98% | - | 13,432 | 0,52% | - | 10,926 | 0,42% | - | 36,332 | 1,40% | - | 140 | 0,01% | - | - | - | - | 24 | 0,00% | - | 303,490 | 11,69% | 2.596.804 | Georgia |

| Hawai | 4 | 137,845 | 37,46% | - | 205,286 | 55,79% | 4 | 21,623 | 5,88% | - | 1.071 | 0,29% | - | 1,477 | 0,40% | - | 343 | 0,09% | - | 306 | 0,08% | - | - | - | - | −67,441 | −18,33% | 367,951 | HOLA |

| Idaho | 4 | 336,937 | 67,17% | 4 | 138.637 | 27,64% | - | 12,292 | 2,45% | - | 7.615 | 1,52% | - | 3.488 | 0,70% | - | 1,469 | 0,29% | - | 1,177 | 0,23% | - | 6 | 0,00% | - | 198.300 | 39,53% | 501,621 | IDENTIFICACIÓN |

| Illinois | 22 | 2,019,421 | 42,58% | - | 2.589.026 | 54,60% | 22 | 103,759 | 2,19% | - | 16,106 | 0,34% | - | 11,623 | 0,25% | - | 57 | 0,00% | - | 2.127 | 0,04% | - | 4 | 0,00% | - | −569,605 | −12,01% | 4.742.123 | ILLINOIS |

| Indiana | 12 | 1.245.836 | 56,65% | 12 | 901,980 | 41,01% | - | 18,531 | 0,84% | - | 16.959 | 0,77% | - | 15,530 | 0,71% | - | 200 | 0,01% | - | 167 | 0,01% | - | 99 | 0,00% | - | 343,856 | 15,63% | 2,199,302 | EN |

| Iowa | 7 | 634,373 | 48,22% | - | 638,517 | 48,54% | 7 | 29,374 | 2,23% | - | 5.731 | 0,44% | - | 3.209 | 0,24% | - | 613 | 0,05% | - | 2,281 | 0,17% | - | 1,465 | 0,11% | - | −4,144 | −0,31% | 1.315.563 | I A |

| Kansas | 6 | 622,332 | 58.04% | 6 | 399,276 | 37,24% | - | 36,086 | 3,37% | - | 7.370 | 0,69% | - | 4.525 | 0,42% | - | 1,254 | 0,12% | - | 1.375 | 0,13% | - | - | - | - | 223,056 | 20,80% | 1.072.218 | Kansas |

| Kentucky | 8 | 872,492 | 56,50% | 8 | 638,898 | 41,37% | - | 23.192 | 1,50% | - | 4.173 | 0,27% | - | 2.896 | 0,19% | - | 923 | 0,06% | - | 1,533 | 0,10% | - | 80 | 0,01% | - | 233,594 | 15,13% | 1,544,187 | Kentucky |

| Luisiana | 9 | 927,871 | 52,55% | 9 | 792,344 | 44,88% | - | 20,473 | 1,16% | - | 14.356 | 0,81% | - | 2.951 | 0,17% | - | 5.483 | 0,31% | - | 1.075 | 0,06% | - | 1,103 | 0,06% | - | 135,527 | 7,68% | 1,765,656 | LA |

| Maine † | 2 | 286,616 | 43,97% | - | 319,951 | 49,09% | 2 | 37,127 | 5,70% | - | 4.443 | 0,68% | - | 3,074 | 0,47% | - | 579 | 0,09% | - | - | - | - | 27 | 0,00% | - | −33,335 | −5,11% | 651,817 | ME |

| Maine-1 | 1 | 148,618 | 42,59% | - | 176,293 | 50,52% | 1 | 20,297 | 5,82% | - | 1,994 | 0,57% | - | 1,479 | 0,42% | - | 253 | 0,07% | - | - | - | - | 17 | 0,00% | - | –27,675 | –7,93% | 348,951 | ME1 |

| Maine-2 | 1 | 137.998 | 45,56% | - | 143.658 | 47,43% | 1 | 16.830 | 5,56% | - | 2,449 | 0,81% | - | 1,595 | 0,53% | - | 326 | 0,11% | - | - | - | - | 10 | 0,00% | - | –5,660 | –1,87% | 302,866 | ME2 |

| Maryland | 10 | 813,797 | 40,18% | - | 1,145,782 | 56,57% | 10 | 53,768 | 2,65% | - | 4.248 | 0,21% | - | 5.310 | 0,26% | - | 919 | 0,05% | - | 176 | 0,01% | - | 1,480 | 0,07% | - | −331,985 | −16,39% | 2,025,480 | Maryland |

| Massachusetts | 12 | 878,502 | 32,50% | - | 1,616,487 | 59,80% | 12 | 173.564 | 6,42% | - | 11,149 | 0,41% | - | 16,366 | 0,61% | - | - | - | - | 2,884 | 0,11% | - | 4.032 | 0,15% | - | −737,985 | −27,30% | 2.702.984 | MAMÁ |

| Michigan | 18 | 1,953,139 | 46,15% | - | 2,170,418 | 51,28% | 18 | 84,165 | 1,99% | - | 1.851 | 0,04% | - | 16.711 | 0,39% | - | 3,791 | 0,09% | - | 2,426 | 0,06% | - | - | - | - | −217,279 | −5,13% | 4.232.501 | MI |

| Minnesota | 10 | 1,109,659 | 45,50% | - | 1,168,266 | 47,91% | 10 | 126,696 | 5,20% | - | 22,166 | 0,91% | - | 5.282 | 0,22% | - | 3,272 | 0,13% | - | 2,294 | 0,09% | - | 1.050 | 0,04% | - | −58,607 | −2,40% | 2,438,685 | Minnesota |

| Misisipí | 7 | 572,844 | 57,62% | 7 | 404,614 | 40,70% | - | 8.122 | 0,82% | - | 2,265 | 0,23% | - | 2.009 | 0,20% | - | 3,267 | 0,33% | - | 450 | 0,05% | - | 613 | 0,06% | - | 168,230 | 16,92% | 994,184 | SRA |

| Misuri | 11 | 1,189,924 | 50,42% | 11 | 1,111,138 | 47,08% | - | 38,515 | 1,63% | - | 9,818 | 0,42% | - | 7.436 | 0,32% | - | 1.957 | 0,08% | - | 1,104 | 0,05% | - | - | - | - | 78,786 | 3,34% | 2,359,892 | mes |

| Montana | 3 | 240,178 | 58,44% | 3 | 137,126 | 33,36% | - | 24,437 | 5,95% | - | 5.697 | 1,39% | - | 1,718 | 0,42% | - | 1,155 | 0,28% | - | 675 | 0,16% | - | 11 | 0,00% | - | 103,052 | 25,07% | 410.997 | MONTE |

| Nebraska † | 5 | 433,862 | 62,25% | 5 | 231,780 | 33,25% | - | 24,540 | 3,52% | - | 3.646 | 0,52% | - | 2,245 | 0,32% | - | 468 | 0,07% | - | 478 | 0,07% | - | - | - | - | 202,082 | 28,99% | 697,019 | nordeste |

| Nebraska-1 | 1 | 142,562 | 58,90% | 1 | 86,946 | 35,92% | - | 10.085 | 4,17% | - | 1.324 | 0,55% | - | 754 | 0,31% | - | 167 | 0,07% | - | 185 | 0,08% | - | - | - | - | 55,616 | 22,98% | 242.023 | NE1 |

| Nebraska-2 | 1 | 131.485 | 56,92% | 1 | 88,975 | 38,52% | - | 8.495 | 3,68% | - | 845 | 0,37% | - | 925 | 0,40% | - | 146 | 0,06% | - | 141 | 0,06% | - | - | - | - | 42,510 | 18,40% | 231,012 | NE2 |

| Nebraska-3 | 1 | 159,815 | 71,35% | 1 | 55,859 | 24,94% | - | 5.960 | 2,66% | - | 1,477 | 0,66% | - | 566 | 0,25% | - | 155 | 0,07% | - | 152 | 0,07% | - | - | - | - | 103,956 | 46,41% | 223,984 | NE3 |

| Nevada | 4 | 301,575 | 49,52% | 4 | 279,978 | 45,98% | - | 15,008 | 2,46% | - | 4.747 | 0,78% | - | 3.311 | 0,54% | - | 621 | 0,10% | - | 415 | 0,07% | - | 3.315 | 0,54% | - | 21.597 | 3,55% | 608,970 | Nevada |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 273,559 | 48,07% | 4 | 266,348 | 46,80% | - | 22.198 | 3,90% | - | 2.615 | 0,46% | - | 2,757 | 0,48% | - | 328 | 0,06% | - | 55 | 0,01% | - | 1,221 | 0,21% | - | 7.211 | 1,27% | 569.081 | NUEVA HAMPSHIRE |

| New Jersey | 15 | 1,284,173 | 40,29% | - | 1,788,850 | 56,13% | 15 | 94,554 | 2,97% | - | 6,989 | 0,22% | - | 6.312 | 0,20% | - | 1.409 | 0,04% | - | 2,215 | 0,07% | - | 2,724 | 0,09% | - | −504,677 | −15,83% | 3,187,226 | Nueva Jersey |

| Nuevo Mexico | 5 | 286,417 | 47,85% | - | 286,783 | 47,91% | 5 | 21,251 | 3,55% | - | 1,392 | 0,23% | - | 2.058 | 0,34% | - | 343 | 0,06% | - | 361 | 0,06% | - | - | - | - | −366 | −0,06% | 598,605 | Nuevo Méjico |

| Nueva York | 33 | 2.403.374 | 35,23% | - | 4.107.697 | 60,21% | 33 | 244.030 | 3,58% | - | 31.599 | 0,46% | - | 7,649 | 0,11% | - | 1,498 | 0,02% | - | 24,361 | 0,36% | - | 1,791 | 0,03% | - | −1,704,323 | −24,98% | 6.821.999 | Nueva York |

| Carolina del Norte | 14 | 1,631,163 | 56.03% | 14 | 1,257,692 | 43.20% | – | – | – | – | 8,874 | 0.30% | – | 12,307 | 0.42% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1,226 | 0.04% | – | 373,471 | 12.83% | 2,911,262 | NC |

| North Dakota | 3 | 174,852 | 60.66% | 3 | 95,284 | 33.06% | – | 9,486 | 3.29% | – | 7,288 | 2.53% | – | 660 | 0.23% | – | 373 | 0.13% | – | 313 | 0.11% | – | – | – | – | 79,568 | 27.60% | 288,256 | ND |

| Ohio | 21 | 2,351,209 | 49.97% | 21 | 2,186,190 | 46.46% | – | 117,857 | 2.50% | – | 26,724 | 0.57% | – | 13,475 | 0.29% | – | 3,823 | 0.08% | – | 6,169 | 0.13% | – | 10 | 0.00% | – | 165,019 | 3.51% | 4,705,457 | OH |

| Oklahoma | 8 | 744,337 | 60.31% | 8 | 474,276 | 38.43% | – | – | – | – | 9,014 | 0.73% | – | 6,602 | 0.53% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 270,061 | 21.88% | 1,234,229 | OK |

| Oregon | 7 | 713,577 | 46.52% | – | 720,342 | 46.96% | 7 | 77,357 | 5.04% | – | 7,063 | 0.46% | – | 7,447 | 0.49% | – | 2,189 | 0.14% | – | 2,574 | 0.17% | – | 3,419 | 0.22% | – | −6,765 | −0.44% | 1,533,968 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 23 | 2,281,127 | 46.43% | – | 2,485,967 | 50.60% | 23 | 103,392 | 2.10% | – | 16,023 | 0.33% | – | 11,248 | 0.23% | – | 14,428 | 0.29% | – | – | – | – | 934 | 0.02% | – | −204,840 | −4.17% | 4,913,119 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 130,555 | 31.91% | – | 249,508 | 60.99% | 4 | 25,052 | 6.12% | – | 2,273 | 0.56% | – | 742 | 0.18% | – | 97 | 0.02% | – | 271 | 0.07% | – | 614 | 0.15% | – | −118,953 | −29.08% | 409,112 | RI |

| South Carolina | 8 | 785,937 | 56.84% | 8 | 565,561 | 40.90% | – | 20,200 | 1.46% | – | 3,519 | 0.25% | – | 4,876 | 0.35% | – | 1,682 | 0.12% | – | 942 | 0.07% | – | – | – | – | 220,376 | 15.94% | 1,382,717 | SC |

| South Dakota | 3 | 190,700 | 60.30% | 3 | 118,804 | 37.56% | – | – | – | – | 3,322 | 1.05% | – | 1,662 | 0.53% | – | 1,781 | 0.56% | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 71,896 | 22.73% | 316,269 | SD |

| Tennessee | 11 | 1,061,949 | 51.15% | 11 | 981,720 | 47.28% | – | 19,781 | 0.95% | – | 4,250 | 0.20% | – | 4,284 | 0.21% | – | 1,015 | 0.05% | – | 613 | 0.03% | – | 2,569 | 0.12% | – | 80,229 | 3.86% | 2,076,181 | TN |

| Texas | 32 | 3,799,639 | 59.30% | 32 | 2,433,746 | 37.98% | – | 137,994 | 2.15% | – | 12,394 | 0.19% | – | 23,160 | 0.36% | – | 567 | 0.01% | – | – | – | – | 137 | 0.00% | – | 1,365,893 | 21.32% | 6,407,637 | TX |

| Utah | 5 | 515,096 | 66.83% | 5 | 203,053 | 26.34% | – | 35,850 | 4.65% | – | 9,319 | 1.21% | – | 3,616 | 0.47% | – | 2,709 | 0.35% | – | 763 | 0.10% | – | 348 | 0.05% | – | 312,043 | 40.49% | 770,754 | UT |

| Vermont | 3 | 119,775 | 40.70% | – | 149,022 | 50.63% | 3 | 20,374 | 6.92% | – | 2,192 | 0.74% | – | 784 | 0.27% | – | 153 | 0.05% | – | 219 | 0.07% | – | 1,789 | 0.61% | – | −29,247 | −9.94% | 294,308 | VT |

| Virginia | 13 | 1,437,490 | 52.47% | 13 | 1,217,290 | 44.44% | – | 59,398 | 2.17% | – | 5,455 | 0.20% | – | 15,198 | 0.55% | – | 1,809 | 0.07% | – | 171 | 0.01% | – | 2,636 | 0.10% | – | 220,200 | 8.04% | 2,739,447 | VA |

| Washington | 11 | 1,108,864 | 44.58% | – | 1,247,652 | 50.16% | 11 | 103,002 | 4.14% | – | 7,171 | 0.29% | – | 13,135 | 0.53% | – | 1,989 | 0.08% | – | 2,927 | 0.12% | – | 2,693 | 0.11% | – | −138,788 | −5.58% | 2,487,433 | WA |

| West Virginia | 5 | 336,475 | 51.92% | 5 | 295,497 | 45.59% | – | 10,680 | 1.65% | – | 3,169 | 0.49% | – | 1,912 | 0.30% | – | 23 | 0.00% | – | 367 | 0.06% | – | 1 | 0.00% | – | 40,978 | 6.32% | 648,124 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 11 | 1,237,279 | 47.61% | – | 1,242,987 | 47.83% | 11 | 94,070 | 3.62% | – | 11,471 | 0.44% | – | 6,640 | 0.26% | – | 2,042 | 0.08% | – | 853 | 0.03% | – | 3,265 | 0.13% | – | −5,708 | −0.22% | 2,598,607 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | 147,947 | 67.76% | 3 | 60,481 | 27.70% | – | 4,625 | 2.12% | – | 2,724 | 1.25% | – | 1,443 | 0.66% | – | 720 | 0.33% | – | 411 | 0.19% | – | – | – | – | 87,466 | 40.06% | 218,351 | WY |

| Totals | 538 | 50,456,002 | 47.86% | 271 | 50,999,897 | 48.38% | 267 | 2,882,955 | 2.74% | – | 448,895 | 0.43% | – | 384,431* | 0.36%* | – | 98,020 | 0.09% | – | 83,714 | 0.08% | – | 51,186 | 0.05% | – | −543,895 | −0.52% | 105,405,100 | US |

Arizona results[edit]

*The Libertarian Party of Arizona had ballot access, but opted to supplant Browne with L. Neil Smith. Thus, in Arizona, Smith received 5,775 votes, constituting 0.38% of the Arizona vote. When adding Smith's 5,775 votes to Browne's 384,431 votes nationwide, that brings the total votes cast for president for the Libertarian Party in 2000 to 390,206, or 0.37% of the vote.

Maine and Nebraska district results[edit]

†Maine and Nebraska each allow for their electoral votes to be split between candidates. In both states, two electoral votes are awarded to the winner of the statewide race and one electoral vote is awarded to the winner of each congressional district.[62][63]

Close states[edit]

States where the margin of victory was less than 1% (55 electoral votes):[64]

- Florida, 0.009% (537 votes) (tipping point state)

- New Mexico, 0.061% (366 votes)

- Wisconsin, 0.22% (5,708 votes)

- Iowa, 0.31% (4,144 votes)

- Oregon, 0.44% (6,765 votes)

States where the margin of victory was more than 1% but less than 5% (84 electoral votes):

- New Hampshire, 1.27% (7,211 votes)

- Maine's 2nd Congressional District, 1.87% (5,660 votes)

- Minnesota, 2.40% (58,607 votes)

- Missouri, 3.34% (78,786 votes)

- Ohio, 3.51% (165,019 votes)

- Nevada, 3.55% (21,597 votes)

- Tennessee, 3.86% (80,229 votes)

- Pennsylvania, 4.17% (204,840 votes)

States where the margin of victory was more than 5% but less than 10% (84 electoral votes):

- Maine, 5.11% (33,335 votes)

- Michigan, 5.13% (217,279 votes)

- Arkansas, 5.44% (50,172 votes)

- Washington, 5.58% (138,788 votes)

- Arizona, 6.29% (96,311 votes)

- West Virginia, 6.32% (40,978 votes)

- Louisiana, 7.68% (135,527 votes)

- Maine's 1st Congressional District, 7.93% (27,675 votes)

- Virginia, 8.04% (220,200 votes)

- Colorado, 8.36% (145,518 votes)

- Vermont, 9.94% (29,247 votes)

Statistics[edit]

[65]

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Glasscock County, Texas 92.47%

- Ochiltree County, Texas 90.72%

- Hansford County, Texas 89.75%

- Harding County, South Dakota 88.92%

- Carter County, Montana 88.84%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Macon County, Alabama 86.80%

- Bronx County, New York 86.28%

- Shannon County, South Dakota 85.36%

- Washington, D.C. 85.16%

- City of Baltimore, Maryland 82.52%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Other)

- San Miguel County, Colorado 17.20%

- Missoula County, Montana 15.03%

- Grand County, Utah 14.94%

- Mendocino County, California 14.68%

- Hampshire County, Massachusetts 14.59%

Ballot access[edit]

| Presidential ticket | Party | Ballot access | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gore / Lieberman | Democratic | 50+DC | 50,999,897 |

| Bush / Cheney | Republican | 50+DC | 50,456,002 |

| Nader / LaDuke | Green | 43+DC | 2,882,955 |

| Buchanan / Foster | Reform | 49 | 448,895 |

| Browne / Olivier | Libertarian | 49+DC★ | 384,431★ |

| Phillips / Frazier | Constitution | 41 | 98,020 |

| Hagelin / Goldhaber | Natural Law | 38 | 83,714 |

★Although the Libertarian Party had ballot access in all fifty United States plus D.C., Browne's name only appeared on the ballot in forty-nine United States plus D.C. The Libertarian Party of Arizona opted to place L. Neil Smith on the ballot in Browne's place. When adding Smith's 5,775 Arizona votes to Browne's 384,431 votes nationwide, that brings the total presidential votes cast for the Libertarian Party in 2000 to 390,206.

Voter demographics[edit]

| Demographic subgroup | Gore | Bush | Other | % of total vote |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total vote | 48 | 48 | 4 | 100 |

| Ideology | ||||

| Liberals | 81 | 13 | 6 | 20 |

| Moderates | 53 | 45 | 2 | 50 |

| Conservatives | 17 | 82 | 1 | 29 |

| Party | ||||

| Democrats | 87 | 11 | 2 | 39 |

| Republicans | 8 | 91 | 1 | 35 |

| Independents | 46 | 48 | 6 | 26 |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | 43 | 54 | 3 | 48 |

| Women | 54 | 44 | 2 | 52 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 42 | 55 | 3 | 81 |

| Black | 90 | 9 | 1 | 10 |

| Asian | 55 | 41 | 4 | 2 |

| Hispanic | 62 | 35 | 3 | 7 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–24 years old | 47 | 47 | 6 | 9 |

| 25–29 years old | 49 | 46 | 5 | 8 |

| 30–49 years old | 48 | 50 | 2 | 45 |

| 50–64 years old | 50 | 48 | 2 | 24 |

| 65 and older | 51 | 47 | 2 | 14 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Gay, lesbian, or bisexual | 71 | 25 | 4 | 4 |

| Heterosexual | 47 | 50 | 3 | 96 |

| Family income | ||||

| Under $15,000 | 58 | 38 | 4 | 7 |

| $15,000–30,000 | 54 | 42 | 4 | 16 |

| $30,000–50,000 | 49 | 48 | 3 | 24 |

| $50,000–75,000 | 46 | 51 | 3 | 25 |

| $75,000–100,000 | 46 | 52 | 2 | 13 |

| Over $100,000 | 43 | 55 | 2 | 15 |

| Region | ||||

| East | 56 | 40 | 4 | 23 |

| Midwest | 48 | 49 | 3 | 26 |

| South | 43 | 56 | 1 | 31 |

| West | 49 | 47 | 4 | 20 |

| Union households | ||||

| Union | 59 | 37 | 4 | 26 |

| Non-union | 45 | 53 | 2 | 74 |

Source: Voter News Service exit poll from the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research (13,225 surveyed)[66]

Aftermath[edit]

After Florida was decided and Gore conceded, Texas Governor George W. Bush became the president-elect and began forming his transition committee.[67] In a speech on December 13, in the Texas House of Representatives chamber,[68] Bush stated he was reaching across party lines to bridge a divided America, saying, "the President of the United States is the President of every single American, of every race, and every background."[69]

Post recount[edit]

On January 6, 2001, a joint session of Congress met to certify the electoral vote. Twenty members of the House of Representatives, most of them members of the all-Democratic Congressional Black Caucus, rose one-by-one to file objections to the electoral votes of Florida. However, pursuant to the Electoral Count Act, any such objection had to be sponsored by both a representative and a senator. No senator would co-sponsor these objections, deferring to the Supreme Court's ruling. Therefore, Gore, who presided in his capacity as President of the Senate, ruled each of these objections out of order.[70] Subsequently, the joint session of Congress on January 7, 2001 certified the electoral votes from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.[71]

Bush took the oath of office on January 20, 2001. He would serve for the next eight years. Gore has not, as of 2021, considered another presidential run, endorsing Howard Dean's candidacy during the 2004 Democratic primary and remaining neutral in the Democratic primaries of 2008, 2016 and 2020.[72][73][74][75]

The first independent recount of undervotes was conducted by the Miami Herald and USA Today. The commission found that under most scenarios for completion of the initiated recounts, Bush would have won the election; however, Gore would have won using the most generous standards for undervotes.[76]

Ultimately, a media consortium — comprising The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Tribune Co. (parent of the Los Angeles Times), Associated Press, CNN, The Palm Beach Post and the St. Petersburg Times[77]—hired NORC at the University of Chicago[78] to examine 175,010 ballots that were collected from the entire state, not just the disputed counties that were recounted; these ballots contained undervotes (ballots with no machine-detected choice made for president) and overvotes (ballots with more than one choice marked). Their goal was to determine the reliability and accuracy of the systems used for the voting process. Based on the NORC review, the media group concluded that if the disputes over all the ballots in question had been resolved by applying statewide any of five standards that would have met Florida's legal standard for recounts, the electoral result would have been reversed and Gore would have won by 60 to 171 votes. (Any analysis of NORC data requires, for each punch ballot, at least two of the three ballot reviewers' codes to agree or instead, for all three to agree.) For all undervotes and overvotes statewide, these five standards are:[7][79][80]

- Prevailing standard – accepts at least one detached corner of a chad and all affirmative marks on optical scan ballots.

- County-by-county standard – applies each county's own standards independently.

- Two-corner standard – accepts at least two detached corners of a chad and all affirmative marks on optical scan ballots.

- Most restrictive standard – accepts only so-called perfect ballots that machines somehow missed and did not count, or ballots with unambiguous expressions of voter intent.

- Most inclusive standard – applies uniform criteria of "dimple or better" on punch marks and all affirmative marks on optical scan ballots.

Such a statewide review including all uncounted votes was a tangible possibility, as Leon County Circuit Court Judge Terry Lewis, whom the Florida Supreme Court had assigned to oversee the statewide recount, had scheduled a hearing for December 13 (mooted by the U.S. Supreme Court's final ruling on the 12th) to consider the question of including overvotes as well as undervotes. Subsequent statements by Judge Lewis and internal court documents support the likelihood of including overvotes in the recount.[81] Florida State University professor of public policy Lance deHaven-Smith observed that, even considering only undervotes, "under any of the five most reasonable interpretations of the Florida Supreme Court ruling, Gore does, in fact, more than make up the deficit".[7] Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting's analysis of the NORC study and media coverage of it supports these interpretations and criticizes the coverage of the study by media outlets such as The New York Times and the other media consortium members.[77]

Further, according to sociologists Christopher Uggen and Jeff Manza, the 2000 election might have gone to Gore if the disenfranchised population of Florida had voted. Florida law disenfranchises convicted felons, requiring individual applications to regain suffrage. In their 2002 American Sociological Review article, Uggen and Manza found that the released felon vote could have altered the outcome of seven senatorial races between 1978 and 2000, and the 2000 presidential election.[82] Matt Ford noted their study concluded "if the state's 827,000 disenfranchised felons had voted at the same rate as other Floridians, Democratic candidate Al Gore would have won Florida—and the presidency — by more than 80,000 votes."[83] The effect of Florida's law is such that in 2014, purportedly "[m]ore than one in ten Floridians – and nearly one in four African-American Floridians – are shut out of the polls because of felony convictions."[84]

Voting machines[edit]

Because the 2000 presidential election was so close in Florida, the United States government and state governments pushed for election reform to be prepared by the 2004 presidential election. Many of Florida's year 2000 election night problems stemmed from usability and ballot design factors with voting systems, including the potentially confusing "butterfly ballot". Many voters had difficulties with the paper-based punch card voting machines and were either unable to understand the required process for voting or unable to perform the process. This resulted in an unusual amount of overvote (voting for more candidates than is allowed) and undervotes (voting for fewer than the minimum candidates, including none at all). Many undervotes were caused by voter error, unmaintained punch card voting booths, or errors having to do merely with the characteristics of punch card ballots (resulting in hanging, dimpled, or pregnant chads).

A proposed solution to these problems was the installation of modern electronic voting machines. The United States presidential election of 2000 spurred the debate about election and voting reform, but it did not end it.

In the aftermath of the election, the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) was passed to help states upgrade their election technology in the hopes of preventing similar problems in future elections. Unfortunately, the electronic voting systems that many states purchased to comply with HAVA actually caused problems in the presidential election of 2004.[85]

Exit polling and declaration of vote winners[edit]

The Voter News Service's reputation was damaged by its treatment of Florida's presidential vote in 2000. Breaking its own guidelines,[citation needed] VNS called the state as a win for Gore 12 minutes before polls closed in the Florida panhandle. Although most of the state is in the Eastern Time Zone, counties in the Florida panhandle, located in the Central Time Zone, had not yet closed their polls. Discrepancies between the results of exit polls and the actual vote count caused the VNS to change its call twice, first from Gore to Bush and then to "too close to call". Due in part to this (and other polling inaccuracies)[citation needed] the VNS was disbanded in 2003.

According to Bush adviser Karl Rove, exit polls early in the afternoon on election day showed Gore winning by three percentage points, but when the networks called the state for Gore, Bush led by about 75,000 votes in raw tallies from the Florida Secretary of State.

Charges of media bias were leveled against the networks by Republicans, who claimed that the networks called states more quickly for Al Gore than for George W. Bush. Congress held hearings on this matter,[86] at which the networks claimed to have no intentional bias in their election night reporting. A study of the calls made on election night 2000 indicated that states carried by Gore were called more quickly than states won by Bush;[87] however, notable states carried by Bush, such as New Hampshire and Florida, were very close, and close states won by Gore, such as Iowa, Oregon, New Mexico and Wisconsin, were called late as well.[88]

The early call of Florida for Gore has been alleged to have cost Bush several close states, including Iowa, New Mexico, Oregon, and Wisconsin.[citation needed] In each of these states, Gore won by less than 10,000 votes, and the polls closed after the networks called Florida for Gore. Because the Florida call was widely seen as an indicator that Gore had won the election, it is possible that it depressed Republican turnout in these states during the final hours of voting, giving Gore the slim margin by which he carried each of them.[citation needed] The call may have also affected the outcome of the Senate election in Washington state, where incumbent Republican Slade Gorton was defeated by approximately 2,000 votes.[citation needed]

Ralph Nader spoiler controversy[edit]

Many Gore supporters claimed that third-party candidate Nader acted as a spoiler in the election, under the presumption that Nader voters would have voted for Gore had Nader not been in the race.[89] Nader received 2.74 percent of the popular vote nationwide, getting 97,000 votes in Florida (by comparison, there were 111,251 overvotes)[90][91] and 22,000 votes in New Hampshire, where Bush beat Gore by 7,000 votes. Winning either state would have won the general election for Gore. Defenders of Nader, including Dan Perkins, argued that the margin in Florida was small enough that Democrats could blame any number of third-party candidates for the defeat, including Workers World Party candidate Monica Moorehead, who received 1,500 votes.[92] But the controversy with Nader also drained energy from the Democratic Party as divisive debate went on in the months leading up to the election.

Nader's reputation was hurt by this perception, which may have hindered his goals as an activist. For example, Mother Jones wrote about the so-called "rank-and-file liberals" who saw Nader negatively after the election and pointed out that Public Citizen, the organization Nader founded in 1971, suffered a drop in contributions. Mother Jones also cited a Public Citizen letter sent out to people interested in Nader's relation with the organization at that time, with the disclaimer: "Although Ralph Nader was our founder, he has not held an official position in the organization since 1980 and does not serve on the board. Public Citizen—and the other groups that Mr. Nader founded—act independently."[93]

Democratic party strategist and Democratic Leadership Council (DLC) chair Al From expressed a different view. In the January 24, 2001, issue[94] of the DLC's Blueprint magazine,[95] he wrote, "I think they're wrong on all counts. The assertion that Nader's marginal vote hurt Gore is not borne out by polling data. When exit pollers asked voters how they would have voted in a two-way race, Bush actually won by a point. That was better than he did with Nader in the race."

In an online article published by Salon.com on Tuesday, November 28, 2000, Texan progressive activist Jim Hightower claimed that in Florida, a state Gore lost by only 537 votes, 24,000 Democrats voted for Nader, while another 308,000 Democrats voted for Bush. According to Hightower, 191,000 self-described liberals in Florida voted for Bush, while fewer than 34,000 voted for Nader.[96]

Press influence on race[edit]

In their 2007 book The Nightly News Nightmare: Network Television's Coverage of US Presidential Elections, 1988–2004, professors Stephen J. Farnsworth and S. Robert Lichter alleged most media outlets influenced the outcome of the election through the use of horse race journalism.[97] Some liberal supporters of Al Gore argued that the media had a bias against Gore and in favor of Bush. Peter Hart and Jim Naureckas, two commentators for Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), called the media "serial exaggerators" and alleged that several media outlets were constantly exaggerating criticism of Gore:[98] they alleged that the media falsely claimed Gore lied when he claimed he spoke in an overcrowded science class in Sarasota, Florida,[98] and also alleged the media gave Bush a pass on certain issues, such as Bush allegedly exaggerating how much money he signed into the annual Texas state budget to help the uninsured during his second debate with Gore in October 2000.[98] In the April 2000 issue of Washington Monthly, columnist Robert Parry also alleged that media outlets exaggerated Gore's supposed claim that he "discovered" the Love Canal neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York during a campaign speech in Concord, New Hampshire on November 30, 1999,[99] when he had only claimed he "found" it after it was already evacuated in 1978 because of chemical contamination.[99] Rolling Stone columnist Eric Boehlert also alleged media outlets exaggerated criticism of Gore as early as July 22, 1999,[100] when Gore, known for being an environmentalist, had a friend release 500 million gallons of water into a drought stricken river to help keep his boat afloat for a photo shoot;[100] Boehlert claimed that media outlets exaggerated the actual number of gallons that were released, as they claimed it was 4 billion.[100]

Color coding[edit]

This is the election that fixed red as a color for the Republican Party and blue for the Democrats. The New York Times used these colors on their full-color election maps. Senior graphics editor Archie Tse, decided that as Republican started with an R then red "was a more natural association". Prior to that color coding choices were inconsistent across the media. In 1976, in its first election map on air, NBC used bulbs that turned red for Carter-won states (Democratic), and blue for Ford (Republican). This original color scheme was based on the British political system, where blue is used to denote the centre-right Conservative Party and red for the centre-left Labour Party (gold or yellow is used for the 'third party' Liberal Democrats). However, the NBC format did not catch on long term, as the media did not follow suit. The unusually long 2000 election helped to cement red and blue as colors in the collective mind.[101]

Effects on future elections and Supreme Court[edit]

A number of subsequent articles have characterized the election in 2000, and the Supreme Court's decision in Bush v. Gore, as damaging the reputation of the Supreme Court, increasing the view of judges as partisan, and decreasing Americans' trust in the integrity of elections.[102][103][104][105][106][107] The number of lawsuits brought over election issues more than doubled following the 2000 election cycle, an increase Richard L. Hasen of UC Irvine School of Law attributes to the "Florida fiasco".[106]

See also[edit]

- 1824 United States presidential election

- 2000 United States gubernatorial elections

- 2000 United States House of Representatives elections

- 2000 United States Senate elections

- First inauguration of George W. Bush

- List of close election results

- Ralph Nader's presidential campaigns

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Electors were elected to all 538 apportioned positions; however, an elector from the District of Columbia pledged to the Gore/Lieberman ticket abstained from casting a vote for president or vice president, bringing the total number of electoral votes cast to 537.

- ^ 267 electors pledged to the Gore/Lieberman ticket were elected; however, an elector from the District of Columbia abstained from casting a vote for president or vice president, bringing the ticket's total number of electoral votes to 266.

- ^ a b One faithless elector from the District of Columbia, Barbara Lett-Simmons, abstained from voting in protest of the District's lack of voting representation in the United States Congress. (D.C. has a non-voting delegate to Congress.) She had been expected to vote for Gore/Lieberman.[61]

References[edit]

- ^ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". Presidency.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ Pruitt, Sarah. "7 Most Contentious U.S. Presidential Elections". HISTORY. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Haddad, Ken (November 7, 2016). "5 of the closest Presidential elections in US history". WDIV. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Fain, Thom. "5 of the closest presidential elections in U.S. history". fosters.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Wood, Richard (July 25, 2017). "Top 9 closest US presidential elections since 1945". Here Is The City. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2019.

- ^ Wolter, Kirk; Jergovic, Diana; Moore, Whitney; Murphy, Joe; O'Muircheartaigh, Colm (February 2003). "Statistical Practice: Reliability of the Uncertified Ballots in the 2000 Presidential Election in Florida" (PDF). The American Statistician. American Statistical Association. 57 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1198/0003130031144. JSTOR 3087271. S2CID 120778921. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 18, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c d deHaven-Smith, Lance, ed. (2005). The Battle for Florida: An Annotated Compendium of Materials from the 2000 Presidential Election. Gainesville, Florida, United States: University Press of Florida. pp. 8, 16, 37–41.

- ^ "Federal Elections 2000: 2000 Presidential Electoral and Popular Vote Table". Federal Election Commission. Archived from the original on July 9, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ Frontline. Boston. October 12, 2004. PBS. WGBH-TV. The Choice. CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ "Interview with John McCain". Dadmag.com. June 4, 2000. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ^ Holmes, Steven A. "After Campaigning on Candor, McCain Admits He Lacked It on Confederate Flag Issue Archived February 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times. April 20, 2000. Retrieved 2015-06-19.

- ^ "West Memphis Kerrey bows out of 2000 presidential race". CNN. December 13, 1998. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ York, Anthony (September 2, 1999) "Life of the Party?" Archived October 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Salon News.

- ^ Dessauer, Carin (April 8, 1998). "Wellstone Launches Presidential Exploratory Committee". CNN. Archived from the original on December 30, 2007. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ "Gore, Lieberman prepare for public debut of Democratic ticket". CNN. August 8, 2000. Archived from the original on November 5, 2008.

- ^ Confessore, Nicholas; Haberman, Maggie (August 9, 2015). "Donald Trump Remains Defiant on News Programs Amid G.O.P. Backlash". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 9, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

Mr. Trump's flirtations with presidential runs span decades—and parties. In 1999, he left the Republican Party to become a member of the Reform Party

- ^ "Trump officially joins Reform Party". CNN. October 25, 1999. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

Trump has not yet formally declared he would seek the Reform Party nomination, but he announced Sunday he was quitting the Republican Party

- ^ "Q&A with Socialist Party presidential candidate Brian Moore". Independent Weekly. October 8, 2008. Archived from the original on January 4, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ^ "Green Party Presidential Ticket – President: Ralph Nader, Vice President: Winona LaDuke". Thegreenpapers.com. Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Libertarian Party Presidential Ticket – President: Harry Browne, Vice President: Art Olivier". The Green Papers. July 3, 2000. Archived from the original on November 6, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Libertarian Party Presidential Ticket". The Green Papers. July 2, 2000. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ^ a b "Bob Bickford "2000 Presidential Status Summary (table)" Ballot Access News June 29, 2000". October 1, 2000. Archived from the original on September 17, 2002. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

- ^ Richard Winger""Natural Law Convention" Ballot Access News October 1, 2000, Volume 16, Number 7". Archived from the original on June 18, 2002. Retrieved June 18, 2002.

- ^ "The Second Gore-Bush Presidential Debate". 2000 Debate Transcript. Commission on Presidential Debates. 2004. Archived from the original on April 3, 2005. Retrieved October 21, 2005.

- ^ "Election 2000 Archive". CNN/AllPolitics.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ^ Rather, Dan. CBSNews.com. Out of the Shadows Archived February 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. August 9, 2000.

- ^ The New York Times. When a Kiss Isn't Just a Kiss Archived September 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. August 20, 2000.

- ^ "Gore's Defeat: Don't Blame Nader". Greens.org. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ Weisberg, Jacob (November 8, 2000). "Why Gore (Probably) Lost". Slate. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ "YouTube". Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ "Nader assails major parties: scoffs at charge he drains liberal vote". CBS. Associated Press. April 6, 2000. Archived from the original on April 10, 2002. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

There is a difference between Tweedledum and Tweedledee, but not that much.

- ^ "CNN Transcript - CNN NewsStand: Presidential Race Intensifies; Gore Campaign Worried Ralph Nader Could Swing Election to Bush - October 26, 2000". Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ "GOP Group To Air Pro-Nader TV Ads". Washingtonpost.com. October 27, 2000. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "Nader rejects concerns about role as spoiler - tribunedigital-baltimoresun". Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2016.

- ^ "The 2000 Campaign: Campaign Briefing Published". The New York Times. September 5, 2000. Archived from the original on May 8, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "CPD: 2000 Debates". www.debates.org. Archived from the original on January 8, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates". Debates.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- ^ "Commission on Presidential Debates". Debates.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2012.