Coordinates: 15°47′38″S 47°52′58″W / 15.79389°S 47.88278°W

| Brasília | |

|---|---|

| Região Administrativa de Brasília Administrative Region of Brasília | |

From the top, clockwise: Monumental Axis seen from the TV Tower; Metropolitan Cathedral at night; facade of the Alvorada Palace; Juscelino Kubitschek bridge in Paranoá Lake; buildings of the South Banking Sector and the National Congress building with the national mast in the Three Powers Plaza at the background. | |

| Nicknames: Capital Federal, BSB, Capital da Esperança | |

| Motto(s): "Venturis ventis"(Latin) "To the coming winds" | |

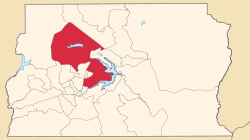

Location in the Federal District | |

| Coordinates: 15°47′38″S 47°52′58″W / 15.79389°S 47.88278°W | |

| Country | Brazil |

| Region | Central-West |

| District | Federal District |

| Founded | April 21, 1960 |

| Area | |

| • Federal capital | 5,802 km2 (2,240.164 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,172 m (3,845 ft) |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Density | 480.827/km2 (1,245.34/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,039,444[2][note 1] |

| • Metro | 4,291,577[1] (3rd) |

| population of the Federal District[citation needed] | |

| Demonym(s) | Brasiliense |

| GDP | |

| • Year | 2015 estimate |

| • Total | $65.338 billion (8th) |

| • Per capita | $21,779 (1st) |

| HDI | |

| • Year | 2014 |

| • Category | 0.839 very high (1st) |

| Time zone | UTC−03:00 (BRT) |

| Postal code | 70000-000 |

| Area code(s) | +55 61 |

| Website | www (in Portuguese) |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| Official name | Brasilia |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 445 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Brasília (/brəˈzɪliə/;[3][4] Portuguese: [bɾaˈziljɐ]) is the federal capital of Brazil and seat of government of the Federal District. The city is located at the top of the Brazilian highlands in the country's center-western region. It was founded by President Juscelino Kubitschek on April 21, 1960, to serve as the new national capital. Brasilia is estimated to be Brazil's third-most populous city.[1] Among major Latin American cities, it has the highest GDP per capita.[5]

Brasilia was a planned city developed by Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer and Joaquim Cardozo in 1956 in a scheme to move the capital from Rio de Janeiro to a more central location. The landscape architect was Roberto Burle Marx.[6][7] The city's design divides it into numbered blocks as well as sectors for specified activities, such as the Hotel Sector, the Banking Sector, and the Embassy Sector. Brasilia was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987 due to its modernist architecture and uniquely artistic urban planning.[8] It was named "City of Design" by UNESCO in October 2017 and has been part of the Creative Cities Network since then.[9]

All three branches of Brazil's federal government are centered in the city: executive, legislative and judiciary. Brasilia also hosts 124 foreign embassies.[10] The city's international airport connects it to all other major Brazilian cities and some international destinations, and it is the third-busiest airport in Brazil. It was one of the main host cities of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and hosted some of the football matches during the 2016 Summer Olympics; it also hosted the 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup.

The city has a unique status in Brazil, as it is an administrative division rather than a legal municipality like other cities in Brazil. Although Brasilia is used as a synonym for the Federal District through synecdoche, the Federal District is composed of 31 administrative regions, only one of which is the area of the originally planned city, also called Plano Piloto. The rest of the Federal District is considered by IBGE to make up Brasilia's metro area.[1]

History[edit]

Background[edit]

Brazil's first capital was Salvador; in 1763 Rio de Janeiro became Brazil's capital and remained so until 1960. During this period, resources tended to be centered in Brazil's southeastern region, and most of the country's population was concentrated near its Atlantic coast.[11] Brasilia's geographically central location fostered a more regionally neutral federal capital. An article of the country's first republican constitution, dated 1891, states that the capital should be moved from Rio de Janeiro to a place close to the country's center.

The plan was conceived in 1827 by José Bonifácio, an advisor to Emperor Pedro I. He presented a plan to the General Assembly of Brazil for a new city called Brasilia, with the idea of moving the capital westward from the heavily populated southeastern corridor. The bill was not enacted because Pedro I dissolved the Assembly.

According to the legend, Italian saint Don Bosco in 1883 had a dream in which he described a futuristic city that roughly fitted Brasilia's location.[12] In Brasilia today, many references to Bosco, who founded the Salesian order, are found throughout the city and one church parish in the city bears his name.[13]

Costa plan[edit]

Juscelino Kubitschek was elected President of Brazil in 1955. Upon taking office in January 1956, in fulfilment of his campaign pledge, he initiated the planning and construction of the new capital. The following year an international jury selected Lúcio Costa's plan to guide the construction of Brazil's new capital, Brasilia. Costa was a student of the famous modernist architect Le Corbusier, and some of modernism's architecture features can be found in his plan. Costa's plan was not as detailed as some of the plans presented by other architects and city planners. It did not include land use schedules, models, population charts or mechanical drawings; however, it was chosen by five out of six jurors because it had the features required to align the growth of a capital city.[14] Even though the initial plan was transformed over time, it oriented much of the construction and most of its features survived.

Brasilia's accession as the new capital and its designation for the development of an extensive interior region inspired the symbolism of the plan. Costa used a cross-axial design indicating the possession and conquest of this new place with a cross,[15] often likened to a dragonfly, an airplane or a bird.[14] Costa's plan included two principal components, the Monumental Axis (east to west) and the Residential Axis (north to south).

The Monumental Axis was assigned political and administrative activities, and is considered the body of the city with the style and simplicity of its buildings, oversized scales, and broad vistas and heights, producing the idea of Monumentality. This axis includes the various ministries, national congress, presidential palace, supreme court building and the television and radio tower.[15]

The Residential Axis was intended to contain areas with intimate character and is considered the most important achievement of the plan; it was designed for housing and associated functions such as local commerce, schooling, recreations and churches, constituted of 96 superblocks limited to six stories buildings and 12 additional superblocks limited to three stories buildings;[14] Costa's intention with superblocks was to have small self-contained and self-sufficient neighborhoods and uniform buildings with apartments of two or three different categories, where he envisioned the integration of upper and middle classes sharing the same residential area.[15] But at that time he did not foresee the growing population in the city. The capacity limit in his plan later caused the formation of many favelas, poorer, more densely populated satellite cities around Brasilia, peopled by migrants from other place in the country. [1]

The urban design of the communal apartment blocks was based on Le Corbusier's Ville Radieuse of 1935, and the superblocks on the North American Radburn layout from 1929.[16]/Visually, the blocks were intended to appear absorbed by the landscape because they were isolated by a belt of tall trees and lower vegetation. Costa attempted to introduce a Brazil that was more equitable, he also designed housing for the working classes that was separated from the upper- and middle-class housing and was visually different, with the intention of avoiding slums (favelas) in the urban periphery.[14][17] The superquadra has been accused of being a space where individuals are oppressed and alienated to a form of spatial segregation.[18]

One of the main objectives of the plan was to allow the free flow of automobile traffic, the plan included lanes of traffic in a north–south direction (seven for each direction) for the Monumental Axis and three arterials (the W3, the Eixo and the L2) for the residential Axis;[15] the cul-de-sac access roads of the superblocks were planned to be the end of the main flow of traffic. And the reason behind the heavy emphasis on automobile traffic is the architect's desire to establish the concept of modernity in every level.

Though automobiles were invented prior to the 20th century, mass production of vehicles in the early 20th made them widely available; thus, they became a symbol of modernity. The two small axes around the Monumental axis provide loops and exits for cars to enter small roads. Some argue that his emphasis of the plan on automobiles caused the lengthening of distances between centers and it attended only the necessities of a small segment of the population who owned cars.[14] But one can not ignore the bus transportation system in the city. The buses routes inside the city operate heavily on W3 and L2. Almost anywhere, including satellite cities, can be reached just by taking the bus and most of the Plano Piloto can be reached without transferring to other buses.

Later when overpopulation turned Brasilia into a dystopia, the transportation system also played an important role in mediating the relationship between the Pilot plan and the satellite cities. Because of overpopulation, the monument axis now has to have traffic lights on it, which violates the concept of modernity and advancement the architect first employed. Additionally, the metro system in Brasilia was mainly built for inhabitants of satellite cities. Though the overpopulation has made Brasilia no longer a pure utopia with incomparable modernity, the later development of traffic lights, buses routes to satellite cities, and the metro system all served as a remedy to the dystopia, enabling the citizens to enjoy the kind of modernity that was not carefully planned.

At the intersection of the Monumental and Residential Axis Costa planned the city center with the transportation center (Rodoviaria), the banking sector and the hotel sector,[15] near to the city center, he proposed an amusement center with theatres, cinemas and restaurants. Costa's Plan is seen as a plan with a sectoral tendency, segregating all the banks, the office buildings, and the amusement center.[14]

One of the main features of Costa's plan was that he presented a new city with its future shape and patterns evident from the beginning. This meant that the original plan included paving streets that were not immediately put into use; the advantage of this was that the original plan is hard to undo because he provided for an entire street network, but on the other hand, is difficult to adapt and mold to other circumstances in the future.[14] In addition, there has been controversy with the monumental aspect of Lúcio Costa's Plan, because it appeared to some as 19th century city planning, not modern 20th century in urbanism.[19]

An interesting analysis can be made of Brasilia within the context of Cold War politics and the association of Lúcio Costa's plan to the symbolism of aviation. From an architectural perspective, the airplane-shaped plan was certainly an homage to Le Corbusier and his enchantment with the aircraft as an architectural masterpiece. However, it is important to also note that Brasilia was constructed soon after the end of World War II. Despite Brazil's minor participation in the conflict, the airplane shape of the city was key in envisioning the country as part of the newly globalized world, together with the victorious Allies.[20] Furthermore, Brasilia is a unique example of modernism both as a guideline for architectural design but also as a principle for organizing society. Modernism in Brasilia is explored in James Holston's book, The Modernist City.[21]

Construction[edit]

Juscelino Kubitschek, president of Brazil from 1956 to 1961, ordered Brasilia's construction, fulfilling the promise of the Constitution and his own political campaign promise. Building Brasilia was part of Juscelino's "fifty years of prosperity in five" plan. Already in 1892, the astronomer Louis Cruls, in the service of the Brazilian government, had investigated the site for the future capital. Lúcio Costa won a contest and was the main urban planner[22] in 1957, with 5550 people competing. Oscar Niemeyer was the chief architect of most public buildings, Joaquim Cardozo was the structural engineer, and Roberto Burle Marx was the landscape designer. Brasilia was built in 41 months, from 1956 to April 21, 1960, when it was officially inaugurated.

Geography[edit]

The city is located at the top of the Brazilian highlands in the country's center-western region.

Paranoá Lake, a large artificial lake, was built to increase the amount of water available and to maintain the region's humidity. It has a marina, and hosts wakeboarders and windsurfers. Diving can also be practiced and one of the main attractions is Vila Amaury, an old village submerged in the lake. This is where the first construction workers of Brasilia used to live.[23]

Climate[edit]

Brasilia has a tropical savanna climate (Aw, according to the Köppen climate classification), milder due to the elevation and with two distinct seasons: the rainy season, from October to April, and the dry season, from May to September.[24] The average temperature is 21.0 °C (69.8 °F).[25] September, at the end of the dry season, has the highest average maximum temperature, 28.4 °C (83.1 °F), and July has major and minor lower maximum average temperature, of 25.1 °C (77.2 °F) and 12.9 °C (55.2 °F), respectively.[25] Average temperatures from September through March are a consistent 22 °C (72 °F).[25] With 241.5 mm (9.5 in), December is the month with the highest rainfall of the year, while June is the lowest, with only 4.9 mm (0.2 in).[25] During the dry season, the city can have very low relative humidity levels, often below 30%.[26]

According to Brazilian National Institute of Meteorology (INMET), the record low temperature was 1.6 °C (34.9 °F) on July 18, 1975, and the record high was 36.4 °C (97.5 °F) on October 18, 2015 [27] and October 8, 2020.[25][28] The highest accumulated rainfall in 24 hours was 132.8 mm (5.2 in) on November 15, 1963.[29]

| Climate data for Brasília (1981–2010, extremes 1961–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 32.6 (90.7) | 31.4 (88.5) | 32.1 (89.8) | 31.6 (88.9) | 31.6 (88.9) | 31.6 (88.9) | 30.8 (87.4) | 33.0 (91.4) | 34.9 (94.8) | 36.4 (97.5) | 33.3 (91.9) | 32.7 (90.9) | 36.4 (97.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26.5 (79.7) | 27.0 (80.6) | 26.7 (80.1) | 26.6 (79.9) | 25.9 (78.6) | 25.0 (77.0) | 25.3 (77.5) | 26.9 (80.4) | 28.4 (83.1) | 28.2 (82.8) | 26.7 (80.1) | 26.3 (79.3) | 26.6 (79.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.6 (70.9) | 21.7 (71.1) | 21.6 (70.9) | 21.3 (70.3) | 20.2 (68.4) | 19.0 (66.2) | 19.0 (66.2) | 20.6 (69.1) | 22.2 (72.0) | 22.4 (72.3) | 21.5 (70.7) | 21.4 (70.5) | 21.0 (69.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) | 18.0 (64.4) | 18.1 (64.6) | 17.5 (63.5) | 15.6 (60.1) | 13.9 (57.0) | 13.7 (56.7) | 15.2 (59.4) | 17.2 (63.0) | 18.1 (64.6) | 18.0 (64.4) | 18.1 (64.6) | 16.8 (62.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.2 (54.0) | 11.0 (51.8) | 14.5 (58.1) | 10.7 (51.3) | 3.2 (37.8) | 3.3 (37.9) | 1.6 (34.9) | 5.0 (41.0) | 9.0 (48.2) | 10.2 (50.4) | 11.4 (52.5) | 11.4 (52.5) | 1.6 (34.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 209.4 (8.24) | 183.0 (7.20) | 211.8 (8.34) | 133.4 (5.25) | 29.7 (1.17) | 4.9 (0.19) | 6.3 (0.25) | 24.1 (0.95) | 46.6 (1.83) | 159.8 (6.29) | 226.9 (8.93) | 241.5 (9.51) | 1,477.4 (58.17) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 17 | 14 | 14 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 17 | 19 | 112 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.2 | 74.7 | 76.8 | 72.2 | 66.2 | 58.7 | 52.7 | 46.8 | 50.3 | 62.8 | 74.5 | 78.0 | 65.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 150.9 | 158.9 | 166.5 | 204.6 | 239.5 | 254.3 | 268.9 | 264.4 | 210.5 | 183.1 | 139.9 | 126.8 | 2,368.3 |

| Source 1: Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia[25] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics[edit]

Ethnic groups[edit]

According to the 2010 IBGE Census, 2,469,489 people resided in Brasilia and its metropolitan area,[31] of whom 1,239,882 were Pardo (Multiracial) (48.2%), 1,084,418 White (42.2%), 198,072 Black (7.7%), 41,522 Asian (1.6%), and 6,128 Amerindian (0.2%).[32]

In 2010, Brasilia was ranked the fourth-most populous city in Brazil after São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Salvador.[33] In 2010, the city had 474,871 opposite-sex couples and 1,241 same-sex couples. The population of Brasilia was 52.2% female and 47.8% male.[32]

In the 1960 census there were almost 140,000 residents in the new Federal district. By 1970 this figure had grown to 537,000. By 2010 the population of the Federal District had surpassed 2,5 million. The city of Brasilia proper, the plano piloto was planned for about 500,000 inhabitants, a figure the plano piloto never surpassed, with a current population of only 214,529,[34] but its metropolitan area within the Federal District has grown past this figure.[35]

From the beginning, the growth of Brasilia was greater than original estimates. According to the original plans, Brasilia would be a city for government authorities and staff. However, during its construction, Brazilians from all over the country migrated to the satellite cities of Brasilia, seeking public and private employment.[36]

At the close of the 20th century, Brasilia was the largest city in the world which had not existed at the beginning of the century.[37] Brasilia has one of the highest population growth rates in Brazil, with annual growth of 2.82%, mostly due to internal migration.

Brasilia's inhabitants include a foreign population of mostly embassy workers as well as large numbers of Brazilian internal migrants. Today, the city has important communities of immigrants and refugees. The city's Human Development Index was 0.936 in 2000 (developed level), and the city's literacy rate was around 95.65%.

Religion[edit]

Christianity, in general, is by far the most prevalent religion in Brazil with Roman Catholicism being the largest denomination.

| Religion | Percentage | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Catholic | 56.62% | 1,455,134 |

| Protestant | 26.88% | 690,982 |

| No religion | 9.20% | 236,528 |

| Spiritist | 3.50% | 89,836 |

| Jewish | 0.04% | 1,103 |

| Muslim | 0.04% | 972 |

Source: IBGE 2010.[38]

Government[edit]

Brasilia does not have mayor and councillors, because the article 32 of the 1988 Brazilian Constitution expressly prohibits that the Federal District be divided in municipalities.

The Federal District is a legal entity of internal public law, which is part of the political-administrative structure of Brazil of a sui generis nature, because it is neither a state nor a municipality, but rather a special entity that accumulates the legislative powers reserved to the states and municipalities, as provided in Article 32, § 1º of the Constitution, which gives it a hybrid nature, both state and municipal.[39]

The executive power of the Federal District was represented by the mayor of the Federal District until 1969, when the position was transformed into governor of the Federal District.[40][41]

The legislative power of the Federal District is represented by the Legislative Chamber of the Federal District, whose nomenclature includes a mixture of legislative assembly (legislative power of the other units of the federation) and of municipal chamber (legislative of the municipalities). The Legislative Chamber is made up of 24 district deputies.[42]

The judicial power which serves the Federal District also serves federal territories as it is constituted, but Brazil does not have any territories. Therefore, the Court of Justice of the Federal District and of the Territories only serves the Federal District.

Part of the budget of the Federal District Government comes from the Constitutional Fund of the Federal District. In 2012, the fund totaled 9.6 billion reais.[43] By 2015, the forecast is 12.4 billion reais, of which more than half (6.4 billion) is spent on public security spending.[44]

International relations[edit]

- Twin towns and sister cities

Brasilia is twinned with:[45]

Abuja, Nigeria[45]

Abuja, Nigeria[45] Asunción, Paraguay[45]

Asunción, Paraguay[45] Brussels, Belgium[45]

Brussels, Belgium[45] Buenos Aires, Argentina (since 2002)[45]

Buenos Aires, Argentina (since 2002)[45] Gaza City, Palestine[45]

Gaza City, Palestine[45] Havana, Cuba[45]

Havana, Cuba[45] Khartoum, Sudan[45]

Khartoum, Sudan[45] Lisbon, Portugal[46]

Lisbon, Portugal[46] Luxor, Egypt[45]

Luxor, Egypt[45] Montevideo, Uruguay[45]

Montevideo, Uruguay[45] Pretoria, South Africa[45]

Pretoria, South Africa[45] Santiago, Chile[45]

Santiago, Chile[45] Tehran, Iran[45]

Tehran, Iran[45] Vienna, Austria[45]

Vienna, Austria[45] Washington, D.C., United States (since 2013)[47]

Washington, D.C., United States (since 2013)[47] Xi'an, China (since 1997)[45]

Xi'an, China (since 1997)[45]

Of these, Abuja and Washington, D.C. were likewise cities specifically planned as the seat of government of their respective countries.

Economy[edit]

The major roles of construction and of services (government, communications, banking and finance, food production, entertainment, and legal services) in Brasilia's economy reflect the city's status as a governmental rather than an industrial center. Industries connected with construction, food processing, and furnishings are important, as are those associated with publishing, printing, and computer software. The gross domestic product (GDP) is divided in Public Administration 54.8%, Services 28.7%, Industry 10.2%, Commerce 6.1%, Agrobusiness 0.2%.[48]

Besides being the political center, Brasilia is an important economic center. It has the highest GDP of cities in Brazil, 99.5 billion reais,[when?] representing 3.76% of the total Brazilian GDP. Most economic activity in the federal capital results from its administrative function. Its industrial planning is studied carefully by the Government of the Federal District. Being a city registered by UNESCO,[clarification needed] the government in Brasilia has opted to encourage the development of non-polluting industries such as software, film, video, and gemology among others, with emphasis on environmental preservation and maintaining ecological balance, preserving the city property.

According to Mercer's city rankings of cost of living for expatriate employees, Brasilia ranks 45th among the most expensive cities in the world in 2012, up from the 70th position in 2010, ranking behind São Paulo (12th) and Rio de Janeiro (13th).

Services[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (April 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

(91% of local GDP, according to the IBGE):

- Government – the public sector is by far the largest employer, accounting for around 40% of the city jobs. Government jobs include all levels, from the federal police to diplomacy, from the transportation bureau to the armed forces;

- Communications – the telephone system used to be a state monopoly, and Brasilia held the HQ of Telebrás, the central state company. One of the enterprises that resulted from the privatization of the system in the 1990s, Brasil Telecom, keeps its HQ in the city; the official Postal Service (Correios) HQ is located in the city as well; as it is the main place of Federal Government news, it is also notable the activities of TV stations, including the main offices of four public networks (TV Brasil/Agência Brasil, TV Câmara, TV Senado and TV Justiça), the regional offices of four major private television networks (Rede Globo, SBT, Rede Bandeirantes and Rede Record) and a main affiliate of RedeTV!;

- Banking and finance – headquarters of the Banco do Brasil and the Caixa Econômica Federal, both controlled by the Federal Government, and the Banco de Brasilia, controlled by the city local government; it is also the site of the headquarters of the Central Bank, the main government regulatory agency of the financial sector;

- Entertainment – the shopping malls Conjunto Nacional, ParkShopping, Pátio Brasil Shopping, Brasilia Shopping, Boulevard Shopping, Taguatinga Shopping, Terraço Shopping, Gilberto Salomão and Iguatemi Brasilia.

- Information technology (Politec, Poliedro, CTIS, among others), and legal services.

- Estructural dump, the main landfill (closed in January 2018)

Industries[edit]

Industries in the city include construction (Paulo Octavio, Via Construções, and Irmãos Gravia among others); food processing (Perdigão, Sadia); furniture making; recycling (Novo Rio, Rexam, Latasa and others); pharmaceuticals (União Química); and graphic industries. The main agricultural products produced in the city are coffee, guavas, strawberries, oranges, lemons, papayas, soybeans, and mangoes. It has over 110,000 cows and it exports wood products worldwide.

The Federal District, where Brasilia is located, has a GDP of R$133,4 billion (about US$64.1 billion), about the same as Belarus according to The Economist. Its share of the total Brazilian GDP is about 3.8%.[49] The Federal District has the largest GDP per capita income of Brazil US$25,062, slightly higher than Belarus.[49]

The city's planned design included specific areas for almost everything, including accommodation, Hotels Sectors North and South. New hotel facilities are being developed elsewhere, such as the hotels and tourism Sector North, located on the shores of Lake Paranoá. Brasilia has a range of tourist accommodation from inns, pensions and hostels to larger international chain hotels. The city's restaurants cater to a wide range of foods from local and regional Brazilian dishes to international cuisine.

Culture[edit]

As a venue for political events, music performances and movie festivals, Brasilia is a cosmopolitan city, with around 124 embassies, a wide range of restaurants and a complete infrastructure ready to host any kind of event. Not surprisingly, the city stands out as an important business/tourism destination, which is an important part of the local economy, with dozens of hotels spread around the federal capital. Traditional parties take place throughout the year.

In June, large festivals known as "festas juninas" are held celebrating Catholic saints such as Saint Anthony of Padua, Saint John the Baptist, and Saint Peter. On September 7, the traditional Independence Day parade is held on the Ministries Esplanade. Throughout the year, local, national, and international events are held throughout the city. Christmas is widely celebrated, and New Year's Eve usually hosts major events celebrated in the city.[50]

The city also hosts a varied assortment of art works from artists like Bruno Giorgi, Alfredo Ceschiatti, Athos Bulcão, Marianne Peretti, Alfredo Volpi, Di Cavalcanti, Dyllan Taxman, Victor Brecheret and Burle Marx, whose works have been integrated into the city's architecture, making it a unique landscape. The cuisine in the city is very diverse. Many of the best restaurants in the city can be found in the Asa Sul district.[51]

The city is the birthplace of Brazilian rock and place of origin of bands like: Legião Urbana, Capital Inicial, Aborto Elétrico, Plebe Rude and Raimundos. Brasilia has the Rock Basement Festival which brings new bands to the national scene. The festival is held in the parking Brasilia National Stadium Mané Garrincha.

Since 1965, the annual Brasilia Festival of Brazilian Cinema is one of the most traditional cinema festivals in Brazil, being compared only to the Brazilian Cinema Festival of Gramado, in Rio Grande do Sul. The difference between both is that the festival in Brasilia still preserves the tradition to only submit and reward Brazilian movies.

The International Dance Seminar in Brasilia has brought top-notch dance to the Federal Capital since 1991. International teachers, shows with choreographers and guest groups and scholarships abroad are some of the hallmarks of the event. The Seminar is the central axis of the DANCE BRAZIL program and is promoted by the DF State Department of Culture in partnership with the Cultural Association Claudio Santoro. [2]

Brasilia has also been the focus of modern-day literature. Published in 2008, The World In Grey: Dom Bosco's Prophecy, by author Ryan J. Lucero, tells an apocalyptical story based on the famous prophecy from the late 19th century by the Italian saint Don Bosco.[52] According to Don Bosco's prophecy:[53] "Between parallels 15 and 20, around a lake which shall be formed; A great civilization will thrive, and that will be the Promised Land". Brasilia lies between the parallels 15° S and 20° S, where an artificial lake (Paranoá Lake) was formed. Don Bosco is Brasilia's patron saint.

American Flagg!, the First Comics comic book series created by Howard Chaykin, portrays Brasilia as a cosmopolitan world capital of culture and exotic romance. In the series, it is a top vacation and party destination. The 2015 Rede Globo series Felizes para Sempre? was set in Brasilia.[54]

Architecture and urbanism[edit]

At the northwestern end of the Monumental Axis there are federal district and municipal buildings, while at the southeastern end, near the middle shore of Lake Paranoá, stand the executive, legislative, and judiciary buildings around the Square of Three Powers, the conceptual heart of the city.[55]

These and other major structures were designed by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer and projected by Brazilian structural engineer Joaquim Cardozo in the style of modern Brazilian architecture. In the Square of Three Powers, he created as a focal point the dramatic Congressional Palace, which is composed of five parts: twin administrative towers surrounded by a large, white concrete dome (the meeting place of the Senate) and by an equally massive concrete bowl (the Chamber of Deputies), which is joined to the dome by an underlying, flat-roofed building.[56] The Congress also occupies various other surrounding buildings, some connected by tunnels. A series of low-lying annexes (largely hidden) surround both ends.

The National Congress building is located in the middle of the Eixo Monumental, the city's main avenue. In front lies a large lawn and reflecting pool. The building faces the Praça dos Três Poderes where the Palácio do Planalto and the Supreme Federal Court are located.

Farther east, on a triangle of land jutting into the lake, it is located the Palace of the Dawn (Palácio da Alvorada; the presidential residence). Between the federal and civic buildings on the Monumental Axis is the Cathedral of Brasilia, considered by many to be Niemeyer's and Cardozo's finest achievement (see photographs of the interior). The parabolically shaped structure is characterized by its 16 gracefully curving supports, which join in a circle 115 feet (35 meters) above the floor of the nave; stretched between the supports are translucent walls of tinted glass. The nave is entered via a subterranean passage rather than conventional doorways. Other notable buildings are Buriti Palace, Itamaraty Palace, the National Theater, and several foreign embassies that creatively embody features of their national architecture. The Brazilian landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx designed landmark modernist gardens for some of the principal buildings.[57]

Both low-cost and luxury buildings were built by the government in Brasilia. The residential zones of the inner city are arranged into superquadras ("superblocks"): groups of apartment buildings inspired in French modernist and bauhaus design and constructed with a prescribed number and type of schools, retail stores, and open spaces. In a not planned spaced in the northern end of Lake Paranoá, separated from the inner city, is a peninsula with many variables homes and a similar city exists on the southern lakeshore. Originally the city planners envisioned extensive public areas along the shores of the artificial lake, but during early development private clubs, hotels, and upscale residences and restaurants gained footholds around the water. Set well apart from the city are satellite cities, including Gama, Ceilândia, Taguatinga, Núcleo Bandeirante, Sobradinho, and Planaltina. These cities, with the exception of Gama and Sobradinho, were not planned.[58]

Monumental civic scale[edit]

The city has been both acclaimed and criticized for its use of modernist architecture on a grand scale and for its somewhat utopian city plan.[59]

After a visit to Brasilia, the French writer Simone de Beauvoir complained that all of its superquadras exuded "the same air of elegant monotony", and other observers have equated the city's large open lawns, plazas, and fields to wastelands. As the city has matured, some of these have gained adornments, and many have been improved by landscaping, giving some observers a sense of "humanized" spaciousness. Although not fully accomplished, the "Brasilia utopia" has produced a city of relatively high quality of life, in which the citizens live in forested areas with sporting and leisure structure (the superquadras) surrounded by small commercial areas, bookstores and cafés; the city is famous for its cuisine and efficiency of transit.[59]

Even these positive features have sparked controversy, expressed in the nickname "ilha da fantasia" ("fantasy island"), indicating the sharp contrast between the city and surrounding regions, marked by poverty and disorganization in the cities of the states of Goiás and Minas Gerais, around Brasilia.[59]

Critics of Brasilia's grand scale have characterized it as a modernist bauhaus platonic fantasy about the future:

Nothing dates faster than people's fantasies about the future. This is what you get when perfectly decent, intelligent, and talented men start thinking in terms of space rather than place; and single rather than multiple meanings. It's what you get when you design for political aspirations rather than real human needs. You get miles of jerry-built platonic nowhere infested with Volkswagens. This, one may fervently hope, is the last experiment of its kind. The utopian buck stops here.

— Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New, Episode 4: "Trouble in Utopia", (1980)

Notable structures[edit]

The Cathedral of Brasilia in the capital of the Federative Republic of Brazil, is an expression of the atheist architect Oscar Niemeyer and the structural engineer Joaquim Cardozo. This concrete-framed hyperboloid structure, seems with its glass roof reaching up, open, to the heavens. The cathedral's structure was finished on May 31, 1970, and only the 70 m (229.66 ft) diameter of the circular area were visible. Niemeyer's and Cardozo's project of Cathedral of Brasilia is based in the hyperboloid of revolution which sections are asymmetric. The hyperboloid structure itself is a result of 16 identical assembled concrete columns. There is controversy as to what these columns, having hyperbolic section and weighing 90 t, represent, some say they are two hands moving upwards to heaven, others associate it to the chalice Jesus used in the last supper and some claim it represent his crown of thorns. The cathedral was dedicated on May 31, 1970.

At the end of the Eixo Monumental ("Monumental Axis") lies the Esplanada dos Ministérios ("Ministries Esplanade"),[60] an open area in downtown Brasilia. The rectangular lawn is surrounded by two eight-lane avenues where many government buildings, monuments and memorials are located. On Sundays and holidays, the Eixo Monumental is closed to cars so that locals may use it as a place to walk, bike, and have picnics under the trees.

Praça dos Três Poderes (Portuguese for Square of the Three Powers) is a plaza in Brasilia. The name is derived from the encounter of the three federal branches around the plaza: the Executive, represented by the Palácio do Planalto (presidential office); the Legislative, represented by the National Congress (Congresso Nacional); and the Judiciary branch, represented by the Supreme Federal Court (Supremo Tribunal Federal). It is a tourist attraction in Brasilia, designed by Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer as a place where the three branches would meet harmoniously.

The Palácio da Alvorada is the official residence of the president of Brazil. The palace was designed, along with the rest of the city of Brasilia, by Oscar Niemeyer and inaugurated in 1958. One of the first structures built in the republic's new capital city, the "Alvorada" lies on a peninsula at the shore of Lake Paranoá. The principles of simplicity and modernity that in the past characterized the great works of architecture motivated Niemeyer. The viewer has an impression of looking at a glass box, softly landing on the ground with the support of thin external columns. The building has an area of 7,000 m2 with three floors consisting of the basement, landing, and second floor. The auditorium, kitchen, laundry, medical center, and administration offices are at basement level. The rooms used by the presidency for official receptions are on the landing. The second floor has four suites, two apartments, and various private rooms which make up the residential part of the palace. The building also has a library, a heated Olympic-sized swimming pool, a music room, two dining rooms and various meeting rooms. A chapel and heliport are in adjacent buildings.

The Palácio do Planalto is the official workplace of the president of Brazil. It is located at the Praça dos Três Poderes in Brasilia. As the seat of government, the term "Planalto" is often used as a metonym for the executive branch of government. The main working office of the President of the Republic is in the Palácio do Planalto. The President and his or her family do not live in it, rather in the official residence, the Palácio da Alvorada. Besides the President, senior advisors also have offices in the "Planalto", including the Vice-President of Brazil and the Chief of Staff. The other Ministries are along the Esplanada dos Ministérios. The architect of the Palácio do Planalto was Oscar Niemeyer, creator of most of the important buildings in Brasilia. The idea was to project an image of simplicity and modernity using fine lines and waves to compose the columns and exterior structures. The Palace is four stories high, and has an area of 36,000 m2. Four other adjacent buildings are also part of the complex.

Education[edit]

The city has six international schools: American School of Brasilia, Brasilia International School (BIS), Escola das Nações, Swiss International School (SIS), Lycée français François-Mitterrand (LfFM) and Maple Bear Canadian School.[61] August 2016 will see the opening of a new international school – the British School of Brasilia. Brasilia has two universities, three university centers, and many private colleges.

The main tertiary educational institutions are: Universidade de Brasilia – University of Brasilia (UnB) (public); Universidade Católica de Brasilia – Catholic University of Brasilia (UCB); Centro Universitário de Brasilia (UniCEUB); Centro Universitário Euroamaricano (Unieuro); Centro Universitário do Distrito Federal (UDF); Universidade Paulista (UNIP); and Instituto de Educação Superior de Brasilia (IESB).

Transportation[edit]

Airport[edit]

Brasilia–Presidente Juscelino Kubitschek International Airport serves the metropolitan area with major domestic and international flights. It is the third busiest Brazilian airport based on passengers and aircraft movements.[62] Because of its strategic location it is a civil aviation hub for the rest of the country.

This makes for a large number of takeoffs and landings and it is not unusual for flights to be delayed in the holding pattern before landing. Following the airport's master plan, Infraero built a second runway, which was finished in 2006. In 2007, the airport handled 11,119,872 passengers.[62] The main building's third floor, with 12 thousand square meters, has a panoramic deck, a food court, shops, four movie theatres with total capacity of 500 people, and space for exhibitions. Brasilia Airport has 136 vendor spaces. The airport is located about 11 km (6.8 mi) from the central area of Brasilia, outside the metro system. The area outside the airport's main gate is lined with taxis as well as several bus line services that connect the airport to Brasilia's central district. The parking lot accommodates 1,200 cars.[63] The airport is serviced by domestic and regional airlines (TAM, GOL, Azul, WebJET, Trip and Avianca), in addition to a number of international carriers. In 2012, Brasilia's International Airport was won by the InfraAmerica consortium, formed by the Brazilian engineering company ENGEVIX and the Argentine Corporacion America holding company, with a 50% stake each.[64] During the 25-year concession, the airport may be expanded to up to 40 million passengers a year.[65]

In 2014 the airport received 15 new boarding bridges, totaling 28 in all. This was the main requirement made by the federal government, which transferred the operation of the terminal to the Inframerica Group after an auction. The group invested R$750 million in the project. In the same year, the number of parking spaces doubled, reaching three thousand. The airport's entrance have a new rooftop cover and a new access road. Furthermore, a VIP room was created on Terminal 1's third floor. The investments resulted an increase the capacity of Brasilia's airport from approximately 15 million passengers per year to 21 million by 2014.[66] Brasilia has direct flights to all states of Brazil and direct international flights to Buenos Aires, Lisbon, Miami, Orlando, Panama City, Lima, Santiago de Chile, Asunción and Cancún.[citation needed][when?]

Road transport[edit]

Like most Brazilian cities, Brasilia has a good network of taxi companies. Taxis from the airport are available outside the terminal, but at times there can be quite a queue of people. Although the airport is not far from the downtown area, taxi prices do seem to be higher than in other Brazilian cities. Booking in advance can be advantageous, particularly if time is limited, and local companies should be able to assist airport transfer or transport requirements.

The Juscelino Kubitschek bridge, also known as the 'President JK Bridge' or the 'JK Bridge', crosses Lake Paranoá in Brasilia. It is named after Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira, former president of Brazil. It was designed by architect Alexandre Chan and structural engineer Mário Vila Verde. Chan won the Gustav Lindenthal Medal[67] for this project at the 2003 International Bridge Conference in Pittsburgh due to "...outstanding achievement demonstrating harmony with the environment, aesthetic merit and successful community participation".

It consists of three 60 m (200 ft) tall asymmetrical steel arches that crisscross diagonally. With a length of 1,200 m (0.75 miles), it was completed in 2002 at a cost of US$56.8 million. The bridge has a pedestrian walkway and is accessible to bicyclists and skaters.

Metro[edit]

The Brasilia Metro is Brasilia's underground metro system. The system has 24 stations on two lines, the Orange and Green lines, along a total network of 42 km (26 mi), covering some of the metropolitan area. Both lines begin at the Central Station and run parallel until the Águas Claras Station. The Brasilia metro is not comprehensive so buses may provide better access to the center.

The metro leaves the Rodoviária (bus station) and goes south, avoiding most of the political and tourist areas. The main purpose of the metro is to serve cities, such as Samambaia, Taguatinga and Ceilândia, as well as Guará and Águas Claras. The satellite cities served are more populated in total than the Plano Piloto itself (the census of 2000 indicated that Ceilândia had 344,039 inhabitants, Taguatinga had 243,575, and the Plano Piloto had approximately 400,000 inhabitants), and most residents of the satellite cities depend on public transportation.[68]

A high-speed railway was planned between Brasilia and Goiânia, the capital of the state of Goias, but it will probably be turned into a regional service linking the capital cities and cities in between, like Anápolis and Alexânia.[69]

Buses[edit]

The main bus hub in Brasilia is the Central Bus Station, located in the crossing of the Eixo Monumental and the Eixão, about 2 km (1.2 mi) from the Three Powers Plaza. The original plan was to have a bus station as near as possible to every corner of Brasilia. Today, the bus station is the hub of urban buses only, some running within Brasilia and others connecting Brasilia to the satellite cities.

In the original city plan, the interstate buses would also stop at the Central Station. Because of the growth of Brasilia (and corresponding growth in the bus fleet), today the interstate buses leave from the older interstate station (called Rodoferroviária) located at the western end of the Eixo Monumental. The Central Bus Station also contains a main metro station. A new bus station was opened in July 2010. It is on Saída Sul (South Exit) near Parkshopping Mall with its metro station, and is also an inter-state bus station, used only to leave the Federal District.

Rail[edit]

There is no passenger rail service in Brasilia, but the Expresso Pequi rail line is planned to link Brasilia and Goiânia.

Light rail[edit]

A 22 km light rail line is planned, estimated to cost between 1 billion reais (US$258 million) and 1.5 billion reais with capacity to transport around 200,000 passengers per day.[70]

Brasilia Public Transportation Statistics[edit]

The average commute time on public transit in Brasilia, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 96 min. 31% of public transit riders, ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 28 min, while 61% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 15.1 km (9.4 mi), while 50% travel for over 12 km (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[71]

Sport[edit]

The main stadiums are the Brasilia National Stadium Mané Garrincha (which was reinaugurated on May 18, 2013), the Serejão Stadium (home for Brasiliense) and the Bezerrão Stadium (home for Gama).

Brasilia was one of the host cities of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2013 FIFA Confederations Cup, for which Brazil is the host nation. Brasilia hosted the opening of the Confederations Cup and hosted 7 World Cup games.[72] Brasilia also hosted the football tournaments during the 2016 Summer Olympics held in Rio de Janeiro.

Brasilia is known as a departing point for the practice of unpowered air sports, sports that may be practiced with hang gliding or paragliding wings. Practitioners of such sports reveal that, because of the city's dry weather, the city offers strong thermal winds and great "cloud-streets", which is also the name for a manoeuvre quite appreciated by practitioners. In 2003, Brasilia hosted the 14th Hang Gliding World Championship, one of the categories of free flying. In August 2005, the city hosted the 2nd stage of the Brazilian Hang Gliding Championship.

Brasilia is the site of the Autódromo Internacional Nelson Piquet which hosted a non-championship round of the 1974 Formula One Grand Prix season. An IndyCar race was cancelled at the last minute in 2015.

The city is also home to Uniceub BRB, one of Brazil's best basketball clubs. Currently, NBB champion (2010, 2011 and 2012). The club hosts some of its games at the 16,000 all-seat Nilson Nelson Gymnasium.

Notable people[edit]

- Juscelino Kubitschek (1902-1976), Brazilian politician, the 21st President of Brazil and the founder of Brasilia (born in Diamantina, Minas Gerais, but founded and lived in Brasilia).

- Felipe Anderson (born 1993), Brazilian professional footballer and attacking midfielder for the Premier League club West Ham United and the Brazil national team (born in Santa Maria, an administrative region located in the Federal District next to Brasilia).

- Kaká (born 1982), Brazilian retired professional footballer who played as an attacking midfielder (born in Gama, an administrative region located in the Federal District next to Brasilia).

- Leandro Brasilia (born 1987), Brazilian footballer who plays for Rio Preto as midfielder (born in Brasilia).

- Athos Bulcão (1918-2008), Brazilian painter and sculptor (born in Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro but lived until his death in Brasilia).

- Cláudio Santoro (1919-1989), Brazilian composer, conductor and violinist (born in Manaus, Amazonas but lived until his death in Brasilia).

- Ketleyn Quadros (born 1987), Brazilian judoka, bronze medalist in the 57 kg weight class at the 2008 Summer Olympics and the first Brazilian woman to win an Olympic medal in an individual sport (born in Ceilândia, an administrative region located in the Federal District next to Brasilia).

- Lúcio (born 1978), Brazilian former footballer who played as a central defender (born in Planaltina, an administrative region located in the Federal District next to Brasilia).

See also[edit]

- List of purpose-built national capitals

Purpose-built Brazilian state capitals[edit]

- Aracaju

- Belo Horizonte

- Boa Vista

- Palmas

- Teresina

Notes[edit]

- ^ The administrative region of Brasília recorded a population of 214,529 in a 2012 survey; IBGE demographic publications do not make this distinction and considers the entire population of the Federal District.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c IBGE: Brasília Archived October 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine IBGE. Retrieved on February 21, 2016. (in Portuguese).

- ^ "Estimativa Populacional 2013" (PDF). Pesquisa Demográfica por Amostra de Domicílios 2011 (in Portuguese). Codeplan. November 9, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ "Brasília". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ "Brasilia" Archived May 10, 2019, at the Wayback Machine (US) and "Brasilia". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Istrate, Emilia. "Global MetroMonitor | Brookings Institution". Brookings.edu. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "Niemeyer e Joaquim Cardozo: uma parceria mágica entre arquiteto e engenheiro" (in Portuguese). Brazil Communication Company. 2012. Archived from the original on January 6, 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Brasília 50 anos" (PDF). Veja (in Portuguese). 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "World Heritage List". Unesco. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ^ "The Brazilian cities Brasília, Paraty and João Pessoa join the UNESCO Creative Cities Network". www.unesco.org. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Archived from the original on October 3, 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- ^ "Lista do Corpo Diplomático e Organismos Internacionais". Cerimonial, Ministério das Relações Exteriores. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Epstein, David G. (1980). Brasília, Plan and Reality: A Study of Planned and Spontaneous Urban Development. University of New Mexico Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780826309594. Archived from the original on April 5, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

- ^ "São João Bosco". Don Bosco Sanctuary website (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ About Brasilia Brazil Archived October 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ a b c d e f g Epstein, David (1973). Brasilia, Plan and Reality : a study of planned and spontaneous urban development. University of California Press. ISBN 0520022033. OCLC 691903.

- ^ a b c d e Wong, Pia (October 1989). Planning and the Unplanned Reality: Brasilia (Master of City Planning, 1988). IURD Working paper series. 499. University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Urban & Regional Development. OCLC 21925988.

- ^ Deckker, Thomas (2016). "Brasília: Life Beyond Utopia". Architectural Design. 86 (3): 88–95. doi:10.1002/ad.2050. ISSN 1554-2769.

Brasília was not, in fact, planned in any meaningful way. The Brazilian architect and planner Lúcio Costa’s entry for the design competition for the new city in 1956 was a series of sketches of ideal urban forms of communal apartment blocks loosely based on Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse of 1935, and ‘superblocks’ of single-family houses based on the North American Radburn layout (1929). He subsequently elaborated these into the Plano Piloto (Pilot Plan), and added the satellite city of Taguatinga.

- ^ Peter William Kellett; Felipe Hernández; Lea Knudsen Allen, eds. (2010). Rethinking the Informal City: Critical Perspectives from Latin America. Berghahn Series:Remapping cultural history. 11. Berghahn Books. p. 58. ISBN 978-1845455828.

- ^ el-Dahdah, Farès, ed. (2005). Lucio Costa: Brasilia's superquadra. CASE. Prestel Verlag. ISBN 3791331574. OCLC 491822493.

- ^ Pessôa, José (Winter 2010). "Lúcio Costa and the Question of Monumentality in his Pilot Plan for Brasilia". Docomomo Journal. 43, Brasilia 1960-2010. ISSN 1380-3204. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ Denicke, Lars (2011). "Fifty years' progress in five: Brasilia—modernization, globalism, and the geopolitics of flight". In Hecht, Gabrielle (ed.). Entangled geographies: empire and technopolitics in the global Cold War. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 185–208. ISBN 978-0262515788. OCLC 731854048.

- ^ James Holston (1989). The Modernist City" An Anthropological Critique of Brasília. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226349794 – via Google Books.

- ^ Banerji, Robin (December 7, 2012). "Brasilia: Does it work as a city?". Archived from the original on September 30, 2018. Retrieved September 30, 2018 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ James Holston (1989). The Modernist City: An Anthropological Critique of Brasilia. University of Chicago Press. p. 341. ISBN 0226349799 – via Google Books.

- ^ A cidade das duas estações Archived May 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ a b c d e f "Normais Climatológicas Do Brasil 1981–2010" (in Portuguese). Instituto Nacional de Meteorologia. Archived from the original on September 5, 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ "DF entra em estado de atenção por causa da baixa umidade do ar". Agência Brasil (in Portuguese). 6 August 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Pegorim, Josélia (October 19, 2015). "Brasília: novo recorde histórico de calor" [Brasília: new historic heat record]. www.climatempo.com.br (in Portuguese). Climatempo. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ "Onda de calor de 2020: reescrevendo a climatologia do BR" [2020 heat wave: rewriting the climatology of BR]. www.climatempo.com.br (in Portuguese). Climatempo. October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- ^ Rodovia com 1,8 km e frio europeu; veja os 'extremos' de Brasília (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ "Station Brasília" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ 2010 IGBE Census Archived May 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Portuguese)

- ^ a b 2010 IGBE Census Archived May 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Portuguese)

- ^ The largest Brazilian cities - 2010 IBGE Census Archived January 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (in Portuguese)

- ^ Keiner, Marco; Koll-Schretzenmayr, Martina; Schmid, Willy A. (2016-12-05). Managing Urban Futures: Sustainability and Urban Growth in Developing Countries. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-92020-9.

- ^ "Population of Brasília". Geocities.com. January 17, 2007. Archived from the original on May 24, 2000. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "Immigration to Brasília". Aboutbrasilia.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Brasília in the World Archived July 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ "Religion in Brasília by IBGE". Sidra.ibge.gov.br. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ "Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988 - Título III, Capítulo V: Do Distrito Federal e dos Territórios" (in Portuguese). Governo do Brasil. 1988. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ "Prefeitos". A História de Brasília (in Portuguese). Info Brasília. Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Por que Brasília não tem prefeito?" (in Portuguese). Portal Terra. 25 August 2010. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ "Sobre a Câmara Legislativa" (in Portuguese). Câmara Legislativa do Distrito Federal. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ "Portal da Transparência - Fundo Constitucional do Distrito Federal". Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ "Ao todo, o GDF poderá contar com um orçamento de R$ 37,2 bilhões para o próximo ano". Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Brasilia Global Partners". Internacional.df.gov.br. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "Lisboa - Geminações de Cidades e Vilas" [Lisbon - Twinning of Cities and Towns]. Associação Nacional de Municípios Portugueses [National Association of Portuguese Municipalities] (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2013.

- ^ Martin Austermuhle (March 15, 2012). "D.C., Welcome Your Newest Sister City: Brasília". Dcist.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "GDP – Division – Federal District". Gdf.df.gov.br. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ a b "Comparing Brazilian states with countries". Economist.com. September 5, 2011. Archived from the original on February 10, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ Brasília Archived May 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ "Culture in Brasília". Travelbite.co.uk. August 9, 2006. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "Dom Bosco – Brasília". Infobrasilia.com.br. April 21, 1965. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ "Dom Bosco – Brasília". Flickr.com. March 24, 2009. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Natália Castro (December 8, 2014). "Maria Fernanda Cândido e Enrique Diaz gravam com Fernando Meirelles nova série da Globo, em Brasilia". O Globo. Revista da TV. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ Brasília Archived June 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ Brasília, Brazil (UNESCO site) Archived May 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ Brasília Archived May 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ Brasília Archived May 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ a b c "Brasília - Britannica".

- ^ "Esplanada dos Ministérios - map - Brasilia". www.aboutbrasilia.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ International schools in Brasília Archived December 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ a b Airport Statistics for 2007 http://www.infraero.gov.br/upload/arquivos/movi/mov.operac.1207.pdf Archived February 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Brasilia International Airport – facts". Aboutbrasilia.com. January 4, 2007. Archived from the original on March 25, 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ^ Brazilian Airport Privatization – Second Round Concessions Archived May 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ Brazil Opens First Expansion at a Privately Operated Airport Archived March 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ Inframerica Group will invest R$ 750 million in Brasilia's Airport Archived May 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- ^ "Bridge Awards". Eswp.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ "Brasília Metro". Metro.df.gov.br. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ Fábio Amato Do G1, em Brasília (June 28, 2012). "G1 - Estudo vai apontar viabilidade de trem entre Brasília, Anápolis e Goiânia - notícias em Distrito Federal". G1.globo.com. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Brasília to start works for US$260mn light rail this year". BNAmericas. 2 April 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ "Brasília Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2017. Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ "Brasilia National Stadium". Government of Brazil. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

External links[edit]

- Regional Administration of Brasilia website

- Government of the Federal District website

Geographic data related to Brasília at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Brasília at OpenStreetMap- Brasilia UNESCO property on Google Arts & Culture

- "The airport: About Inframerica". Aeroporto de Brasíla. 2020.