| Sugar Ray Robinson | |

|---|---|

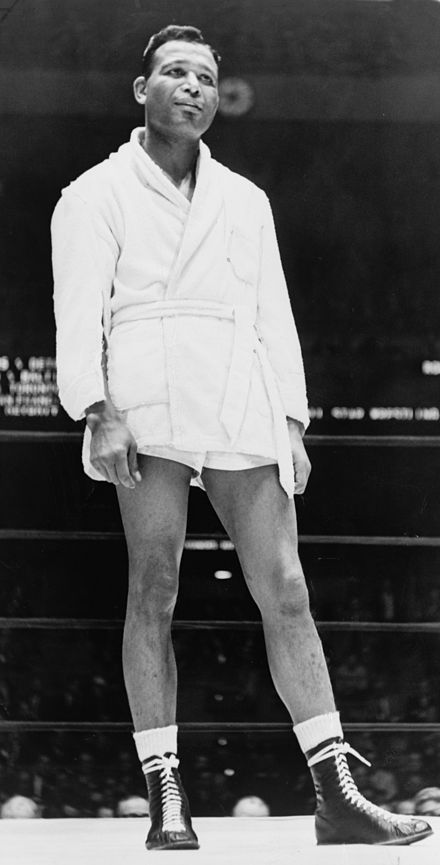

Sugar Ray Robinson in the Madison Square Garden in 1966 | |

| Statistics | |

| Real name | Walter (Walker) Smith Jr. |

| Weight(s) | |

| Height | 5 ft 11 in (180 cm) |

| Reach | 72½ in |

| Born | May 3, 1921 Ailey, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | April 12, 1989 (aged 67) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 200 |

| Wins | 173 |

| Wins by KO | 109 |

| Losses | 19 |

| Draws | 6 |

| No contests | 2 |

| Medal record Men's amateur boxing Representing United States New York Golden Gloves 1939 New York Featherweight 1940 New York Lightweight Intercity Golden Gloves 1939 Chicago Featherweight 1940 New York Lightweight |

Sugar Ray Robinson (born Walker Smith Jr.; May 3, 1921 – April 12, 1989) was an American professional boxer who competed from 1940 to 1965. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.[1] He is widely regarded as one of the greatest boxers of all time.

Robinson was a dominant amateur, but his exact amateur record is not known. It is usually listed as 85–0 with 69 knockouts, 40 in the first round. However it has been reported he lost to Billy Graham and Patsy Pesca as a teenager under his given name, Walker Smith Jr. He turned professional in 1940 at the age of 19 and by 1951 had a professional record of 128–1–2 with 84 knockouts. From 1943 to 1951 Robinson went on a 91-fight unbeaten streak, the third-longest in professional boxing history.[2][3] Robinson held the world welterweight title from 1946 to 1951, and won the world middleweight title in the latter year. He retired in 1952, only to come back two-and-a-half years later and regain the middleweight title in 1955. He then became the first boxer in history to win a divisional world championship five times (a feat he accomplished by defeating Carmen Basilio in 1958 to regain the middleweight championship). Robinson was named "fighter of the year" twice: first for his performances in 1942, then nine years and over 90 fights later, for his efforts in 1951. Historian Bert Sugar ranked Robinson as the greatest fighter of all time and in 2002, Robinson was also ranked number one on The Ring magazine's list of "80 Best Fighters of the Last 80 Years".[4] As of October 2020, BoxRec ranks Robinson as the fourth greatest boxer, pound-for-pound, of all time.[5]

Renowned for his classy and flamboyant lifestyle outside the ring,[6] Robinson is credited with being the originator of the modern sports "entourage". After his boxing career ended, Robinson attempted a career as an entertainer, but it was not successful. He struggled financially until his death in 1989. In 2006, he was featured on a commemorative stamp by the United States Postal Service.[7]

Early life[edit]

Robinson was born Walker Smith Jr. in Ailey, Georgia, to Walker Smith Sr. and Leila Hurst.[8] Robinson was the youngest of three children; his eldest sister Marie was born in 1917, and his other sister Evelyn in 1919. His father was a cotton, peanut, and corn farmer in Georgia, who moved the family to Detroit where he initially found work in construction.[8] According to Robinson, Smith Sr. later worked two jobs to support his family—cement mixer and sewer worker. "He had to get up at six in the morning and he'd get home close to midnight. Six days a week. The only day I really saw him was Sunday ... I always wanted to be with him more."[9]

His parents separated, and he moved with his mother to the New York City neighborhood of Harlem at the age of twelve. Robinson originally aspired to be a doctor, but after dropping out of DeWitt Clinton High School (in the Bronx) in ninth grade he switched his goal to boxing.[10] When he was 15, he attempted to enter his first boxing tournament but was told he needed to first obtain an AAU membership card. However, he could not procure one until he was eighteen years old. He received his name when he circumvented the AAU's age restriction by borrowing a birth certificate from his friend Ray Robinson.[11] Subsequently told that he was "sweet as sugar" by a lady in the audience at a fight in Watertown, New York, Smith Jr. became known as "Sugar" Ray Robinson.[12][13]

Robinson idolized Henry Armstrong and Joe Louis as a youth, and actually lived on the same block as Louis in Detroit when Robinson was 11 and Louis was 17.[12] Outside the ring, Robinson got into trouble frequently as a youth, and was involved with a street gang.[12] He married at 16. The couple had one son, Ronnie, and divorced when Robinson was 19.[12] He reportedly finished his amateur career with an 85–0 record with 69 knockouts – 40 coming in the first round, though this has been disputed.[14] He won the New York Golden Gloves featherweight championship in 1939 (def.Louis Valentine points 3), and the New York Golden Gloves lightweight championship in 1940 (def.Andy Nonella KO 2).[11]

Boxing career[edit]

Early career[edit]

Robinson made his professional debut on October 4, 1940, winning by a second-round stoppage over Joe Echevarria. Robinson fought five more times in 1940, winning each time, with four wins coming by way of knockout. In 1941, he defeated world champion Sammy Angott, future champion Marty Servo and former champion Fritzie Zivic. The Robinson-Angott fight was held above the lightweight limit, since Angott did not want to risk losing his lightweight title. Robinson defeated Zivic in front of 20,551 at Madison Square Garden—one of the largest crowds in the arena to that date.[15] Robinson won the first five rounds, according to Joseph C. Nichols of The New York Times, before Zivic came back to land several punches to Robinson's head in the sixth and seventh rounds.[15] Robinson controlled the next two rounds, and had Zivic in the ninth. After a close tenth round, Robinson was announced as the winner on all three scorecards.[15]

In 1942 Robinson knocked out Zivic in the tenth round in a January rematch. The knockout loss was only the second of Zivic's career in more than 150 fights.[16] Robinson knocked him down in the ninth and tenth rounds before the referee stopped the fight. Zivic and his corner protested the stoppage; James P. Dawson of The New York Times stated "[t]hey were criticizing a humane act. The battle had been a slaughter, for want of a more delicate word."[16] Robinson then won four consecutive bouts by knockout, before defeating Servo in a controversial split decision in their May rematch. After winning three more fights, Robinson faced Jake LaMotta, who would become one of his more prominent rivals, for the first time in October. He defeated LaMotta by a unanimous decision, although he failed to get Jake down. Robinson weighed 145 lb (66 kg) compared to 157.5 for LaMotta, but he was able to control the fight from the outside for the entire bout, and actually landed the harder punches during the fight.[17] Robinson then won four more fights, including two against Izzy Jannazzo, from October 19 to December 14. For his performances, Robinson was named "Fighter of the Year". He finished 1942 with a total of 14 wins and no losses.

Robinson built a record of 40–0 before losing for the first time to LaMotta in a 10-round re-match.[18] LaMotta, who had a 16 lb (7.3 kg) weight advantage over Robinson, knocked Robinson out of the ring in the eighth round, and won the fight by decision. The fight took place in Robinson's former home town of Detroit, and attracted a record crowd.[18] After being controlled by Robinson in the early portions of the fight, LaMotta came back to take control in the later rounds.[18] After winning the third LaMotta fight less than three weeks later, Robinson then defeated his childhood idol: former champion Henry Armstrong. Robinson fought Armstrong only because the older man was in need of money. By now Armstrong was an old fighter, and Robinson later stated that he carried the former champion.

On February 27, 1943, Robinson was inducted into the United States Army, where he was again referred to as Walker Smith.[19] Robinson had a 15-month military career. Robinson served with Joe Louis, and the pair went on tours where they performed exhibition bouts in front of US Army troops. Robinson got into trouble several times while in the military. He argued with superiors who he felt were discriminatory against him, and refused to fight exhibitions when he was told African American soldiers were not allowed to watch them.[12][20] In late March 1944, Robinson was stationed at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, waiting to ship out to Europe, where he was scheduled to perform more exhibition matches. But on March 29, Robinson disappeared from his barracks. When he woke up on April 5 in Fort Jay Hospital on Governor's Island, he had missed his sailing for Europe and was under suspicion of deserting. He himself reported falling down the stairs in his barracks on the 29th, but said that he had complete amnesia, and he could not remember any events from that moment until the 5th. According to his file, a stranger had found him in the street on April 1 and helped him to a hospital. In his examination report, a doctor at Fort Jay concluded that Robinson's version of events was sincere.[21] He was examined by military authorities, who claimed he suffered from a mental deficiency.[22] Robinson was granted an honorable discharge on June 3, 1944. He later wrote that unfair press coverage of the incident had "branded" him as a "deserter".[23] Robinson maintained his close friendship with Louis from their time in military service, and the two went into business together after the war. They planned to start a liquor distribution business in New York City, but were denied a license due to their race.[24]

Besides the loss in the LaMotta rematch, the only other mark on Robinson's record during this period was a 10-round draw against José Basora in 1945.

Welterweight champion[edit]

By 1946, Robinson had fought 75 fights to a 73–1–1 record, and beaten every top contender in the welterweight division. However, he refused to cooperate with the Mafia, which controlled much of boxing at the time, and was denied a chance to fight for the welterweight championship.[25] Robinson was finally given a chance to win a title against Tommy Bell on December 20, 1946. Robinson had already beaten Bell once by decision in 1945. The two fought for the title vacated by Servo, who had himself lost twice to Robinson in non-title bouts. In the fight, Robinson, who only a month before had been involved in a 10-round brawl with Artie Levine, was knocked down by Bell. The fight was called a "war", but Robinson was able to pull out a close 15-round decision, winning the vacant World Welterweight title.[26]

In 1948 Robinson fought five times, but only one bout was a title defense. Among the fighters he defeated in those non-title bouts was future world champion Kid Gavilán in a close, controversial 10-round fight. Gavilán hurt Robinson several times in the fight, but Robinson controlled the final rounds with a series of jabs and left hooks.[27] In 1949, he boxed 16 times, but again only defended his title once. In that title fight, a rematch with Gavilán, Robinson again won by decision. The first half of the bout was very close, but Robinson took control in the second half. Gavilán would have to wait two more years to begin his own historic reign as welterweight champion. The only boxer to match Robinson that year was Henry Brimm, who fought him to a 10-round draw in Buffalo.

Robinson fought 19 times in 1950. He successfully defended his welterweight title for the last time against Charley Fusari. Robinson won a lopsided 15-round decision, knocking Fusari down once. Robinson donated all but $1 of his purse for the Fusari fight to cancer research.[28] In 1950 Robinson fought George Costner, who had also taken to calling himself "Sugar" and stated in the weeks leading up to the fight that he was the rightful possessor of the name. "We better touch gloves, because this is the only round", Robinson said as the fighters were introduced at the center of the ring. "Your name ain't Sugar, mine is."[29] Robinson then knocked Costner out in 2 minutes and 49 seconds.

Jimmy Doyle incident[edit]

In June 1947, after four non-title bouts, Robinson was scheduled to defend his title for the first time in a bout against Jimmy Doyle. Robinson initially backed out of the fight because he had a dream that he was going to kill Doyle. A priest and a minister convinced him to fight. His dream was proven to be true.[30] On June 25, 1947 Robinson dominated Doyle and scored a decisive knockout in the eighth round that knocked Doyle unconscious and resulted in Doyle's death later that night.[31] Robinson said that the impact of Doyle's death was "very trying".[A]

After his death, criminal charges were threatened against Robinson in Cleveland, up to and including murder, though none actually materialized. After learning of Doyle's intentions of using the bout's money to buy his mother a house, Robinson gave Doyle's mother the money from his next four bouts so she could purchase herself a home, fulfilling her son's intention.[32][33]

Middleweight champion[edit]

It is stated in his autobiography that one of the main considerations for his move up to middleweight was the increasing difficulty he was having in making the 147 lb (67 kg) welterweight weight limit.[34] However, the move up would also prove beneficial financially, as the division then contained some of the biggest names in boxing. Vying for the Pennsylvania state middleweight title in 1950, Robinson defeated Robert Villemain. Later that year, in defense of that crown, he defeated Jose Basora, with whom he had previously drawn. Robinson's 50-second, first-round knockout of Basora set a record that would stand for 38 years. In October 1950, Robinson knocked out Bobo Olson a future middleweight title holder.

On February 14, 1951, Robinson and LaMotta met for the sixth time. The fight would become known as The St. Valentine's Day Massacre. Robinson won the undisputed World Middleweight title with a 13th round technical knockout.[35] Robinson outboxed LaMotta for the first 10 rounds, then unleashed a series of savage combinations on LaMotta for three rounds,[12] finally stopping the champion for the first time in their legendary six-bout series—and dealing LaMotta his first legitimate knockout loss in 95 professional bouts.[36] LaMotta had lost by knockout to Billy Fox earlier in his career. However, that fight was later ruled to have been fixed and LaMotta was sanctioned for letting Fox win. That bout, and some of the other bouts in the six-fight Robinson-LaMotta rivalry, was depicted in the Martin Scorsese film Raging Bull. "I fought Sugar Ray so often, I almost got diabetes", LaMotta later said.[13] Robinson won five of his six bouts with LaMotta.

After winning his second world title, he embarked on a European tour which took him all over the Continent. Robinson traveled with his flamingo-pink Cadillac, which caused quite a stir in Paris,[37] and an entourage of 13 people, some included "just for laughs".[38] He was a hero in France due to his recent defeat of LaMotta—the French hated LaMotta for defeating Marcel Cerdan in 1949 and taking his championship belt (Cerdan died in a plane crash en route to a rematch with LaMotta).[12] Robinson met President of France Vincent Auriol at a ceremony attended by France's social upper crust.[39] During his fight in Berlin against Gerhard Hecht, Robinson was disqualified when he knocked his opponent with a punch to the kidney: a punch legal in the US, but not Europe.[31] The fight was later declared a no-contest. In London, Robinson lost the world middleweight title to British boxer Randolph Turpin in a sensational bout.[40] Three months later in a rematch in front of 60,000 fans at the Polo Grounds,[31] he knocked Turpin out in ten rounds to recover the title. In that bout Robinson was leading on the cards but was cut by Turpin. With the fight in jeopardy, Robinson let loose on Turpin, knocking him down, then getting him to the ropes and unleashing a series of punches that caused the referee to stop the bout.[41] Following Robinson's victory, residents of Harlem danced in the streets.[42] In 1951, Robinson was named Ring Magazine's "Fighter of the Year" for the second time.[43]

In 1952 he fought a rematch with Olson, winning by a decision. He next defeated former champion Rocky Graziano by a third-round knockout, then challenged World Light heavyweight champion Joey Maxim.[44] In the Yankee Stadium bout with Maxim, Robinson built a lead on all three judges' scorecards, but the 103 °F (39 °C) temperature in the ring took its toll.[13] The referee, Ruby Goldstein, was the first victim of the heat, and had to be replaced by referee Ray Miller. The fast-moving Robinson was the heat's next victim – at the end of round 13, he collapsed and failed to answer the bell for the next round,[13] suffering the only knockout of his career.

On June 25, 1952, after the Maxim bout, Robinson gave up his title and retired with a record of 131–3–1–1. He began a career in show business, singing and tap dancing. After about three years, the decline of his businesses and the lack of success in his performing career made him decide to return to boxing. He resumed training in 1954.

Comeback[edit]

In 1955 Robinson returned to the ring. Although he had been inactive for two and a half years, his work as a dancer kept him in peak physical condition: in his autobiography, Robinson states that in the weeks leading up to his debut for a dancing engagement in France, he ran five miles every morning, and then danced for five hours each night. Robinson even stated that the training he did in his attempts to establish a career as a dancer were harder than any he undertook during his boxing career.[45] He won five fights in 1955, before losing a decision to Ralph 'Tiger' Jones. He bounced back, however, and defeated Rocky Castellani by a split decision, then challenged Bobo Olson for the world middleweight title. He won the middleweight championship for the third time with a second-round knockout—his third victory over Olson. After his comeback performance in 1955, Robinson expected to be named fighter of the year. However, the title went to welterweight Carmen Basilio. Basilio's handlers had lobbied heavily for it on the basis that he had never won the award, and Robinson later described this as the biggest disappointment of his professional career. "I haven't forgotten it to this day, and I never will", Robinson wrote in his autobiography.[46] Robinson and Olson fought for the last time in 1956, and Robinson closed the four-fight series with a fourth-round knockout.

In 1957 Robinson lost his title to Gene Fullmer. Fullmer used his aggressive, forward moving style to control Robinson, and knocked him down in the fight.[47] Robinson, however, noticed that Fullmer was vulnerable to the left hook. Fullmer headed into their May rematch as a 3–1 favorite.[48] In the first two rounds Robinson followed Fullmer around the ring, however in the third round he changed tactics and made Fullmer come to him.[48] At the start of the fourth round Robinson came out on the attack and stunned Fullmer, and when Fullmer returned with his own punches, Robinson traded with him, as opposed to clinching as he had done in their earlier fight. The fight was fairly even after four rounds.[48] But in the fifth, Robinson was able to win the title back for a fourth time by knocking out Fullmer with a lightning fast, powerful left hook.[48] Boxing critics have referred to the left-hook which knocked out Fullmer as "the perfect punch".[49] It marked the first time in 44 career fights that Fullmer had been knocked out, and when someone asked Robinson after the fight how far the left hook had travelled, Robinson replied: "I can't say. But he got the message."[48]

Later that year, he lost his title to Basilio in a rugged 15 round fight in front of 38,000 at Yankee Stadium,[50] but regained it for a record fifth time when he beat Basilio in the rematch. Robinson struggled to make weight, and had to go without food for nearly 20 hours leading up to the bout. He badly damaged Basilio's eye early in the fight, and by the seventh round it was swollen shut.[51] The two judges gave the fight to Robinson by wide margins: 72–64 and 71–64. The referee scored the fight for Basilio 69–64, and was booed loudly by the crowd of 19,000 when his decision was announced.[51] The first fight won the "Fight of the Year" award from The Ring magazine for 1957 and the second fight won the "Fight of the Year" award for 1958.

Decline[edit]

Robinson knocked out Bob Young in the second round in Boston in his only fight in 1959. A year later, he defended his title against Paul Pender. Robinson entered the fight as a 5–1 favorite, but lost a split decision in front of 10,608 at Boston Garden.[52] The day before the fight Pender commented that he planned to start slowly, before coming on late. He did just that and outlasted the aging Robinson, who, despite opening a cut over Pender's eye in the eighth round, was largely ineffective in the later rounds.[52] An attempt to regain the crown for an unheard of sixth time proved beyond Robinson. Despite Robinson's efforts, Pender won by decision in that rematch. On December 3 of that year, Robinson and Fullmer fought a 15-round draw for the WBA middleweight title, which Fullmer retained. In 1961, Robinson and Fullmer fought for a fourth time, with Fullmer retaining the WBA middleweight title by a unanimous decision. The fight would be Robinson's last title bout.

Robinson spent the rest of the 1960s fighting 10-round contests. In October 1961 Robinson defeated future world champion Denny Moyer by a unanimous decision. A 12–5 favorite, the 41-year-old Robinson defeated the 22-year-old Moyer by staying on the outside, rather than engaging him.[53] In their rematch four months later, Moyer defeated Robinson on points, as he pressed the action and made Robinson back up throughout the fight. Moyer won 7–3 on all three judges scorecards.[54] Robinson lost twice more in 1962, before winning six consecutive fights against mostly lesser opposition. In February 1963 Robinson lost by a unanimous decision to former world champion and fellow Hall of Famer Joey Giardello. Giardello knocked Robinson down in the fourth round, and the 43-year-old took until the count of nine to rise to his feet.[55] Robinson was also nearly knocked down in the sixth round, but was saved by the bell. He rallied in the seventh and eight rounds, before struggling in the final two.[55] He then embarked on an 18-month boxing tour of Europe.

Robinson's second no-contest bout came in September 1965 in Norfolk, Virginia in a match with an opponent who turned out to be an impostor. Boxer Neil Morrison, at the time a fugitive and accused robber, signed up for the fight as Bill Henderson, a capable club fighter. The fight was a fiasco, with Morrison being knocked down twice in the first round and once in the second before the disgusted referee, who said "Henderson put up no fight", walked out of the ring. Robinson was initially given a TKO in 1:20 of the second round after the "obviously frightened" Morrison laid himself down on the canvas. Robinson fought for the final time in November 1965. He lost by a unanimous decision to Joey Archer.[56] Famed sports author Pete Hamill mentioned that one of the saddest experiences of his life was watching Robinson lose to Archer. He was even knocked down and Hamill pointed out that Archer had no knockout punch at all; Archer admitted afterward that it was only the second time he had knocked an opponent down in his career. The crowd of 9,023 at the Civic Arena in Pittsburgh gave Robinson several standing ovations, even while he was being thoroughly outperformed by Archer.[56]

On November 11, 1965, Robinson announced his retirement from boxing, saying: "I hate to go too long campaigning for another chance."[57] Robinson retired from boxing with a record of 173–19–6 (2 no contests) with 109 knockouts in 200 professional bouts, ranking him among the all-time leaders in knockouts.

Professional boxing record[edit]

| 200 fights | 173 wins | 19 losses |

| By knockout | 109 | 1 |

| By decision | 64 | 18 |

| By disqualification | 0 | 0 |

| Draws | 6 | |

| No contests | 2 | |

| No. | Result | Record | Opponent | Type | Round, time | Date | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | Loss | 173–19–6 (2) | Joey Archer | UD | 10 | November 10, 1965 | Civic Arena, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 199 | Win | 173–18–6 (2) | Rudolph Bent | TKO | 3 (10), 2:20 | October 20, 1965 | Community Arena, Steubenville, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 198 | Win | 172–18–6 (2) | Peter Schmidt | UD | 10 | October 1, 1965 | Cambria County War Memorial Arena, Johnstown, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 197 | Win | 171–18–6 (2) | Harvey McCullough | UD | 10 | September 23, 1965 | Philadelphia Athletic Club, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 196 | NC | 170–18–6 (2) | Neil Morrison | NC | 2 (10), 1:20 | September 15, 1965 | Norfolk Arena, Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. | |

| 195 | Loss | 170–18–6 (1) | Stan Harrington | UD | 10 | August 10, 1965 | Honolulu International Center, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. | |

| 194 | Win | 170–17–6 (1) | Harvey McCullough | UD | 10 | July 27, 1965 | Richmond Arena, Richmond, Virginia, U.S. | |

| 193 | Loss | 169–17–6 (1) | Ferd Hernandez | SD | 10 | July 12, 1965 | Hacienda, Paradise, Nevada, U.S. | |

| 192 | Win | 169–16–6 (1) | Harvey McCullough | UD | 10 | June 24, 1965 | Washington Coliseum, Washington, D.C., U.S. | |

| 191 | Loss | 168–16–6 (1) | Stan Harrington | UD | 10 | June 1, 1965 | Honolulu International Center, Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. | |

| 190 | Loss | 168–15–6 (1) | Memo Ayón | UD | 10 | May 24, 1965 | Plaza de Toros El Toreo, Tijuana, Mexico | |

| 189 | Win | 168–14–6 (1) | Rocky Randell | KO | 3 (10), 0:58 | April 28, 1965 | Norfolk Municipal Auditorium, Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. | |

| 188 | Win | 167–14–6 (1) | Earl Bastings | KO | 1 (10), 2:34 | April 3, 1965 | Sports Center, Savannah, Georgia, U.S. | |

| 187 | Win | 166–14–6 (1) | Jimmy Beecham | KO | 2 (10), 1:48 | March 6, 1965 | National Stadium, Kingston, Jamaica | |

| 186 | Draw | 165–14–6 (1) | Fabio Bettini | PTS | 10 | November 27, 1964 | Palazzetto dello Sport, Rome, Italy | |

| 185 | Win | 165–14–5 (1) | Jean Beltritti | PTS | 10 | November 14, 1964 | Palais des Sports de Marseille, Marseille, France | |

| 184 | Win | 164–14–5 (1) | Jean Baptiste Rolland | PTS | 10 | November 7, 1964 | Stade Helitas, Caen, France | |

| 183 | Win | 163–14–5 (1) | Jackie Cailleau | PTS | 10 | October 24, 1964 | Palais des Sports, Nice, France | |

| 182 | Win | 162–14–5 (1) | Johnny Angel | TKO | 6 (8) | October 12, 1964 | London Hilton, London, England | |

| 181 | Win | 161–14–5 (1) | Yoland Leveque | PTS | 10 | September 28, 1964 | Palais des Sports, Paris, France | |

| 180 | Loss | 160–14–5 (1) | Mick Leahy | PTS | 10 | September 3, 1964 | Paisley Ice Rink, Paisley, Scotland | |

| 179 | Draw | 160–13–5 (1) | Art Hernández | MD | 10 | July 27, 1964 | Omaha City Auditorium, Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. | |

| 178 | Win | 160–13–4 (1) | Clarence Riley | TKO | 6 (10), 2:40 | July 8, 1964 | Wahconah Park, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 177 | Win | 159–13–4 (1) | Gaylord Barnes | UD | 10 | May 19, 1964 | Portland Exposition Building, Portland, Maine, U.S. | |

| 176 | Win | 158–13–4 (1) | Armand Vanucci | PTS | 10 | December 9, 1963 | Palais des Sports, Paris, France | |

| 175 | Win | 157–13–4 (1) | Andre Davier | PTS | 10 | November 29, 1963 | Palais des Sports, Grenoble, France | |

| 174 | Win | 156–13–4 (1) | Emiel Sarens | KO | 8 (10) | November 16, 1963 | Palais des Sports, Brussels, Belgium | |

| 173 | Draw | 155–13–4 (1) | Fabio Bettini | PTS | 10 | November 9, 1963 | Palais des Sports de Gerland, Lyon, France | |

| 172 | Win | 155–13–3 (1) | Armand Vanucci | PTS | 10 | October 14, 1963 | Palais des Sports, Paris, France | |

| 171 | Loss | 154–13–3 (1) | Joey Giardello | UD | 10 | June 24, 1963 | Philadelphia Convention Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 170 | Win | 154–12–3 (1) | Maurice Roblet | KO | 3 (10) | May 4, 1963 | Palais des Sports Léopold-Drolet, Quebec, Canada | |

| 169 | Win | 153–12–3 (1) | Billy Thornton | KO | 3 (10), 0:50 | March 11, 1963 | Lewiston Armory, Lewiston, Maine, U.S. | |

| 168 | Win | 152–12–3 (1) | Bernie Reynolds | KO | 4 (10) | February 25, 1963 | Estadio Quisqueya, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic | |

| 167 | Win | 151–12–3 (1) | Ralph Dupas | SD | 10 | January 30, 1963 | Miami Beach Convention Center, Miami Beach, Florida, U.S. | |

| 166 | Win | 150–12–3 (1) | Georges Estatoff | TKO | 6 (10) | November 10, 1962 | Palais des Sports de Gerland, Lyon, France | |

| 165 | Win | 149–12–3 (1) | Diego Infantes | KO | 2 (10), 1:15 | October 17, 1962 | Wiener Stadthalle, Vienna, Austria | |

| 164 | Loss | 148–12–3 (1) | Terry Downes | PTS | 10 | September 25, 1962 | Empire Pool, London, England | |

| 163 | Loss | 148–11–3 (1) | Phil Moyer | SD | 10 | July 9, 1962 | Los Angeles Sports Arena, Los Angeles, California, U.S. | |

| 162 | Win | 148–10–3 (1) | Bobby Lee | KO | 2 (10), 2:38 | April 27, 1962 | National Stadium, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago | |

| 161 | Loss | 147–10–3 (1) | Denny Moyer | UD | 10 | February 17, 1962 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 160 | Win | 147–9–3 (1) | Wilf Greaves | KO | 8 (10), 0:43 | December 8, 1961 | Civic Arena, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 159 | Win | 146–9–3 (1) | Al Hauser | TKO | 6 (10), 1:59 | November 20, 1961 | Rhode Island Auditorium, Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. | |

| 158 | Win | 145–9–3 (1) | Denny Moyer | UD | 10 | October 21, 1961 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 157 | Win | 144–9–3 (1) | Wilf Greaves | SD | 10 | September 25, 1961 | Convention Arena, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 156 | Loss | 143–9–3 (1) | Gene Fullmer | UD | 15 | March 4, 1961 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | For NBA middleweight title |

| 155 | Draw | 143–8–3 (1) | Gene Fullmer | SD | 15 | December 3, 1960 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | For NBA middleweight title |

| 154 | Loss | 143–8–2 (1) | Paul Pender | SD | 15 | June 10, 1960 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | For NYSAC and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 153 | Win | 143–7–2 (1) | Tony Baldoni | KO | 1 (10), 1:40 | April 2, 1960 | Baltimore Coliseum, Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. | |

| 152 | Loss | 142–7–2 (1) | Paul Pender | SD | 15 | January 22, 1960 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | Lost NYSAC and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 151 | Win | 142–6–2 (1) | Bob Young | KO | 2 (10), 1:18 | December 14, 1959 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 150 | Win | 141–6–2 (1) | Carmen Basilio | SD | 15 | March 25, 1958 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | Won NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 149 | Loss | 140–6–2 (1) | Carmen Basilio | SD | 15 | September 23, 1957 | Yankee Stadium, Bronx, New York, U.S. | Lost NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 148 | Win | 140–5–2 (1) | Gene Fullmer | KO | 5 (15), 1:27 | May 1, 1957 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | Won NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 147 | Loss | 139–5–2 (1) | Gene Fullmer | UD | 15 | January 2, 1957 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | Lost NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 146 | Win | 139–4–2 (1) | Bob Provizzi | UD | 10 | November 10, 1956 | New Haven Arena, New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. | |

| 145 | Win | 138–4–2 (1) | Bobo Olson | KO | 4 (15), 2:51 | May 18, 1956 | Wrigley Field, Los Angeles, California, U.S. | Retained NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 144 | Win | 137–4–2 (1) | Bobo Olson | KO | 2 (15), 2:51 | December 9, 1955 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | Won NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 143 | Win | 136–4–2 (1) | Rocky Castellani | SD | 10 | July 22, 1955 | Cow Palace, Daly City, California, U.S. | |

| 142 | Win | 135–4–2 (1) | Garth Panter | UD | 10 | May 4, 1955 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 141 | Win | 134–4–2 (1) | Ted Olla | TKO | 3 (10), 2:15 | April 14, 1955 | Milwaukee Arena, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, U.S. | |

| 140 | Win | 133–4–2 (1) | Johnny Lombardo | SD | 10 | March 29, 1955 | Cincinnati Gardens, Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 139 | Loss | 132–4–2 (1) | Ralph Jones | UD | 10 | January 19, 1955 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 138 | Win | 132–3–2 (1) | Joe Rindone | KO | 6 (10), 1:37 | January 5, 1955 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 137 | Loss | 131–3–2 (1) | Joey Maxim | RTD | 13 (15) | June 25, 1952 | Yankee Stadium, Bronx, New York, U.S. | For NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring light heavyweight titles |

| 136 | Win | 131–2–2 (1) | Rocky Graziano | KO | 3 (15), 1:53 | April 14, 1952 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | Retained NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 135 | Win | 130–2–2 (1) | Bobo Olson | UD | 15 | March 13, 1952 | San Francisco Civic Auditorium, San Francisco, California, U.S. | Retained NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 134 | Win | 129–2–2 (1) | Randolph Turpin | TKO | 10 (15), 2:52 | September 12, 1951 | Polo Grounds, New York City, New York, U.S. | Won NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 133 | Loss | 128–2–2 (1) | Randolph Turpin | PTS | 15 | July 10, 1951 | Earls Court Arena, London, England | Lost NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 132 | Win | 128–1–2 (1) | Cyrille Delannoit | RTD | 3 (10) | July 1, 1951 | Palazzo Dello Sport, Turin, Italy | |

| 131 | NC | 127–1–2 (1) | Gerhard Hecht | NC | 2 (10) | June 24, 1951 | Waldbühne, Berlin, Germany | |

| 130 | Win | 127–1–2 | Jean Walzack | TKO | 6 (10) | June 16, 1951 | Palais des Sports, Liège, Belgium | |

| 129 | Win | 126–1–2 | Jan de Bruin | TKO | 8 (10) | June 10, 1951 | Sportpaleis, Antwerp, Belgium | |

| 128 | Win | 125–1–2 | Jean Wanes | UD | 10 | May 26, 1951 | Hallenstadion, Zürich, Switzerland | |

| 127 | Win | 124–1–2 | Kid Marcel | TKO | 5 (10) | May 21, 1951 | Palais des Sports, Paris, France | |

| 126 | Win | 123–1–2 | Don Ellis | KO | 1 (10), 1:36 | April 9, 1951 | Municipal Auditorium, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, U.S. | |

| 125 | Win | 122–1–2 | Holly Mims | UD | 10 | April 5, 1951 | Miami Stadium, Miami, Florida, U.S. | |

| 124 | Win | 121–1–2 | Jake LaMotta | TKO | 13 (15), 2:04 | February 14, 1951 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | Won NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring middleweight titles |

| 123 | Win | 120–1–2 | Hans Stretz | TKO | 5 (10) | December 25, 1950 | Haus der Technik, Frankfurt, Germany | |

| 122 | Win | 119–1–2 | Robert Villemain | TKO | 9 (10) | December 22, 1950 | Palais des Sports, Paris, France | |

| 121 | Win | 118–1–2 | Jean Walzack | UD | 10 | December 16, 1950 | Palais des Expositions, Geneva, Switzerland | |

| 120 | Win | 117–1–2 | Luc van Dam | KO | 4 (10) | December 9, 1950 | Palais des Sports, Brussels, Belgium | |

| 119 | Win | 116–1–2 | Jean Stock | TKO | 2 (10) | November 27, 1950 | Palais des Sports, Paris, France | |

| 118 | Win | 115–1–2 | Bobby Dykes | MD | 10 | November 8, 1950 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 117 | Win | 114–1–2 | Bobo Olson | KO | 12 (15), 1:19 | October 26, 1950 | Philadelphia Convention Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | Retained Pennsylvania State middleweight title |

| 116 | Win | 113–1–2 | Joe Rindone | TKO | 6 (10), 0:55 | October 16, 1950 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 115 | Win | 112–1–2 | Billy Brown | UD | 10 | September 4, 1950 | Coney Island Velodrome, Brooklyn, New York, U.S. | |

| 114 | Win | 111–1–2 | José Basora | KO | 1 (15), 0:55 | August 25, 1950 | Scranton Stadium, Scranton, Pennsylvania, U.S | Retained Pennsylvania State middleweight title |

| 113 | Win | 110–1–2 | Charley Fusari | PTS | 15 | August 9, 1950 | Roosevelt Stadium, Jersey City, New Jersey, U.S | Retained NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring welterweight titles |

| 112 | Win | 109–1–2 | Robert Villemain | UD | 15 | June 5, 1950 | Philadelphia Municipal Stadium, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S | Won vacant Pennsylvania State middleweight title |

| 111 | Win | 108–1–2 | Ray Barnes | UD | 10 | April 28, 1950 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 110 | Win | 107–1–2 | Cliff Beckett | TKO | 3 (10), 1:45 | April 21, 1950 | Memorial Hall, Columbus, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 109 | Win | 106–1–2 | George Costner | KO | 1 (10), 2:49 | March 22, 1950 | Philadelphia Convention Hall, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 108 | Win | 105–1–2 | Jean Walzack | UD | 10 | February 27, 1950 | St. Louis Arena, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. | |

| 107 | Win | 104–1–2 | Aaron Wade | KO | 3 (10) | February 22, 1950 | Municipal Auditorium, Savannah, Georgia, U.S. | |

| 106 | Win | 103–1–2 | Johnny Dudley | KO | 2 (12), 0:40 | February 18, 1950 | Municipal Stadium, Orlando, Florida, U.S. | |

| 105 | Win | 102–1–2 | Al Mobley | TKO | 6 (10) | February 13, 1950 | Coliseum Arena, Miami, Florida, U.S. | |

| 104 | Win | 101–1–2 | George LaRover | TKO | 4 (10), 1:38 | January 30, 1950 | New Haven Arena, New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. | |

| 103 | Win | 100–1–2 | Vern Lester | KO | 5 (10), 0:12 | November 13, 1949 | Coliseum Arena, New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. | |

| 102 | Win | 99–1–2 | Don Lee | UD | 10 | November 9, 1949 | Denver Auditorium Arena, Denver, Colorado, U.S. | |

| 101 | Win | 98–1–2 | Charley Dodson | KO | 3 (10), 0:20 | September 12, 1949 | Houston City Auditorium, Houston, Texas, U.S. | |

| 100 | Win | 97–1–2 | Benny Evans | TKO | 5 (10), 2:56 | September 9, 1949 | Omaha City Auditorium, Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. | |

| 99 | Win | 96–1–2 | Steve Belloise | RTD | 7 (10) | August 24, 1949 | Yankee Stadium, Bronx, New York, U.S. | |

| 98 | Win | 95–1–2 | Kid Gavilán | UD | 15 | July 11, 1949 | Philadelphia Municipal Stadium, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | Retained NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring welterweight titles |

| 97 | Win | 94–1–2 | Cecil Hudson | KO | 5 (10) | June 20, 1949 | Rhode Island Auditorium, Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. | |

| 96 | Win | 93–1–2 | Freddie Flores | TKO | 3 (10), 2:41 | June 7, 1949 | Page Arena, New Bedford, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 95 | Win | 92–1–2 | Earl Turner | TKO | 8 (10), 1:51 | April 20, 1949 | Oakland Auditorium, Oakland, California, U.S. | |

| 94 | Win | 91–1–2 | Don Lee | UD | 10 | April 11, 1949 | Omaha City Auditorium, Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. | |

| 93 | Win | 90–1–2 | Bobby Lee | UD | 10 | March 25, 1949 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 92 | Draw | 89–1–2 | Henry Brimm | SD | 10 | February 15, 1949 | Buffalo Memorial Auditorium, Buffalo, New York, U.S. | |

| 91 | Win | 89–1–1 | Young Gene Buffalo | KO | 1 (10), 2:55 | February 10, 1949 | Kingston Armory, Kingston, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 90 | Win | 88–1–1 | Bobby Lee | UD | 10 | November 15, 1948 | Philadelphia Arena, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 89 | Win | 87–1–1 | Kid Gavilán | UD | 10 | September 23, 1948 | Yankee Stadium, Bronx New York, U.S. | |

| 88 | Win | 86–1–1 | Bernard Docusen | UD | 15 | June 28, 1948 | Comiskey Park, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | Retained NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring welterweight titles |

| 87 | Win | 85–1–1 | Henry Brimm | UD | 10 | March 16, 1948 | Buffalo Memorial Auditorium, Buffalo, New York, U.S. | |

| 86 | Win | 84–1–1 | Ossie Harris | UD | 10 | March 4, 1948 | Toledo Sports Arena, Toledo, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 85 | Win | 83–1–1 | Chuck Taylor | TKO | 6 (15), 2:07 | December 19, 1947 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | Retained NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring welterweight titles |

| 84 | Win | 82–1–1 | Billy Nixon | TKO | 6 (10), 2:10 | December 10, 1947 | Elizabeth Armory, Elizabeth, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 83 | Win | 81–1–1 | California Jackie Wilson | TKO | 7 (10), 1:35 | October 28, 1947 | Olympic Auditorium, Los Angeles, California, U.S. | |

| 82 | Win | 80–1–1 | Flashy Sebastian | KO | 1 (10), 1:02 | August 29, 1947 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 81 | Win | 79–1–1 | Sammy Secreet | KO | 1 (10), 1:50 | August 21, 1947 | Rubber Bowl, Akron, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 80 | Win | 78–1–1 | Jimmy Doyle | TKO | 8 (15) | June 24, 1947 | Cleveland Arena, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. | Retained NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring welterweight titles Doyle died of injuries sustained from the fight[58] |

| 79 | Win | 77–1–1 | Georgie Abrams | SD | 10 | May 16, 1947 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 78 | Win | 76–1–1 | Eddie Finazzo | TKO | 4 (10), 2:30 | April 8, 1947 | Memorial Hall, Kansas City, Kansas, U.S. | |

| 77 | Win | 75–1–1 | Freddie Wilson | TKO | 3 (10), 1:10 | April 3, 1947 | Akron Armory, Akron, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 76 | Win | 74–1–1 | Bernie Miller | TKO | 3 (10), 1:32 | March 27, 1947 | Dorsey Park, Miami, Florida, U.S. | |

| 75 | Win | 73–1–1 | Tommy Bell | UD | 15 | December 20, 1946 | Cleveland Arena, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. | Won vacant NBA, NYSAC, and The Ring welterweight titles |

| 74 | Win | 72–1–1 | Artie Levine | KO | 10 (10), 2:41 | November 6, 1946 | Cleveland Arena, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 73 | Win | 71–1–1 | Cecil Hudson | KO | 6 (10), 2:58 | November 1, 1946 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 72 | Win | 70–1–1 | Ossie Harris | UD | 10 | October 7, 1946 | Forbes Field, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 71 | Win | 69–1–1 | Sidney Miller | KO | 3 (10), 1:52 | September 25, 1946 | Twin City Bowl, Elizabeth, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 70 | Win | 68–1–1 | Vinnie Vines | KO | 6 (10), 2:46 | August 15, 1946 | Hawkins Stadium, Albany, New York, U.S. | |

| 69 | Win | 67–1–1 | Joe Curcio | KO | 2 (10), 0:10 | July 12, 1946 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 68 | Win | 66–1–1 | Norman Rubio | PTS | 10 | June 25, 1946 | Roosevelt Stadium, Union City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 67 | Win | 65–1–1 | Freddie Wilson | KO | 2 (10), 2:00 | June 12, 1946 | Worcester Auditorium, Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 66 | Win | 64–1–1 | Freddie Flores | KO | 5 (10), 2:52 | March 21, 1946 | Golden Gate Arena, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 65 | Win | 63–1–1 | Izzy Jannazzo | UD | 10 | March 14, 1946 | Fifth Regiment Armory, Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. | |

| 64 | Win | 62–1–1 | Sammy Angott | UD | 10 | March 4, 1946 | Duquesne Gardens, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 63 | Win | 61–1–1 | Cliff Beckett | KO | 4 (10), 0:40 | February 27, 1946 | St. Louis Arena, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. | |

| 62 | Win | 60–1–1 | O'Neil Bell | KO | 2 (10), 1:10 | February 15, 1946 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 61 | Win | 59–1–1 | Tony Riccio | TKO | 4 (10), 2:16 | February 5, 1946 | Elizabeth Armory, Elizabeth, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 60 | Win | 58–1–1 | Dave Clark | TKO | 2 (10), 2:22 | January 14, 1946 | Duquesne Gardens, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 59 | Win | 57–1–1 | Vic Dellicurti | UD | 10 | December 4, 1945 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 58 | Win | 56–1–1 | Jimmy Mandell | TKO | 5 (10), 1:31 | September 18, 1945 | Buffalo Memorial Auditorium, Buffalo, New York, U.S. | |

| 57 | Win | 55–1–1 | Jimmy McDaniels | KO | 2 (10), 1:23 | June 15, 1945 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 56 | Draw | 54–1–1 | José Basora | SD | 10 | May 14, 1945 | Philadelphia Convention Hall, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 55 | Win | 54–1 | Jake LaMotta | UD | 10 | February 23, 1945 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 54 | Win | 53–1 | George Costner | KO | 1 (10), 2:55 | February 14, 1945 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 53 | Win | 52–1 | Tommy Bell | UD | 10 | January 16, 1945 | Cleveland Arena, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 52 | Win | 51–1 | Billy Furrone | TKO | 2 (10), 2:28 | January 10, 1945 | Uline Arena, Washington, D.C., U.S. | |

| 51 | Win | 50–1 | George Martin | TKO | 7 (10), 3:00 | December 22, 1944 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 50 | Win | 49–1 | Sheik Rangel | TKO | 2 (10), 2:50 | December 12, 1944 | Philadelphia Convention Hall, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 49 | Win | 48–1 | Vic Dellicurti | UD | 10 | November 24, 1944 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 48 | Win | 47–1 | Lou Woods | TKO | 9 (10), 2:10 | October 27, 1944 | Chicago Stadium, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 47 | Win | 46–1 | Izzy Jannazzo | KO | 2 (10), 1:10 | October 13, 1944 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 46 | Win | 45–1 | Henry Armstrong | UD | 10 | August 27, 1943 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 45 | Win | 44–1 | Ralph Zannelli | UD | 10 | July 1, 1943 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 44 | Win | 43–1 | Freddie Cabral | KO | 1 (10), 2:20 | April 30, 1943 | Boston Garden, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. | |

| 43 | Win | 42–1 | Jake LaMotta | UD | 10 | February 26, 1943 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 42 | Win | 41–1 | California Jackie Wilson | MD | 10 | February 19, 1943 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 41 | Loss | 40–1 | Jake LaMotta | UD | 10 | February 5, 1943 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 40 | Win | 40–0 | Al Nettlow | TKO | 3 (10) | December 14, 1942 | Philadelphia Convention Hall, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 39 | Win | 39–0 | Izzy Jannazzo | KO | 8 (10), 2:43 | December 1, 1942 | Cleveland Arena, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. | |

| 38 | Win | 38–0 | Vic Dellicurti | UD | 10 | November 6, 1942 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 37 | Win | 37–0 | Izzy Jannazzo | UD | 10 | October 19, 1942 | Philadelphia Arena, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 36 | Win | 36–0 | Jake LaMotta | UD | 10 | October 2, 1942 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 35 | Win | 35–0 | Tony Motisi | KO | 1 (10), 2:41 | August 27, 1942 | Comiskey Park, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| 34 | Win | 34–0 | Reuben Shank | KO | 2 (10), 2:26 | August 21, 1942 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 33 | Win | 33–0 | Sammy Angott | UD | 10 | July 31, 1942 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 32 | Win | 32–0 | Marty Servo | SD | 10 | May 28, 1942 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 31 | Win | 31–0 | Dick Banner | KO | 2 (10), 0:32 | April 30, 1942 | Minneapolis Armory, Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. | |

| 30 | Win | 30–0 | Harvey Dubs | TKO | 6 (10), 2:45 | April 17, 1942 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 29 | Win | 29–0 | Norman Rubio | TKO | 7 (12), 3:00 | March 20, 1942 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 28 | Win | 28–0 | Maxie Berger | TKO | 2 (12), 1:43 | February 20, 1942 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 27 | Win | 27–0 | Fritzie Zivic | TKO | 10 (12), 0:31 | January 16, 1942 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 26 | Win | 26–0 | Fritzie Zivic | UD | 10 | October 31, 1941 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 25 | Win | 25–0 | Marty Servo | UD | 10 | September 25, 1941 | Philadelphia Convention Hall, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 24 | Win | 24–0 | Maxie Shapiro | TKO | 3 (10), 2:04 | September 19, 1941 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 23 | Win | 23–0 | Maurice Arnault | TKO | 1 (8), 1:29 | August 29, 1941 | Atlantic City Convention Hall, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 22 | Win | 22–0 | Carl Guggino | TKO | 3 (8), 2:47 | August 27, 1941 | Queensboro Arena, Queens, New York U.S. | |

| 21 | Win | 21–0 | Sammy Angott | UD | 10 | July 21, 1941 | Shibe Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 20 | Win | 20–0 | Pete Lello | TKO | 4 (8), 1:48 | July 2, 1941 | Polo Grounds, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 19 | Win | 19–0 | Mike Evans | KO | 2 (8), 0:52 | June 16, 1941 | Shibe Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 18 | Win | 18–0 | Nick Castiglione | KO | 1 (10), 1:21 | May 19, 1941 | Philadelphia Arena, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 17 | Win | 17–0 | Victor Troise | TKO | 1 (8), 2:39 | May 10, 1941 | Ridgewood Grove, Brooklyn, New York, U.S. | |

| 16 | Win | 16–0 | Joe Ghnouly | TKO | 3 (8), 2:07 | April 30, 1941 | Uline Arena, Washington, D.C., U.S. | |

| 15 | Win | 15–0 | Charley Burns | KO | 1 (10), 2:35 | April 24, 1941 | Waltz Dream Arena, Atlantic City, New Jersey, U.S. | |

| 14 | Win | 14–0 | Jimmy Tygh | TKO | 1 (10), 1:51 | April 14, 1941 | Philadelphia Arena, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 13 | Win | 13–0 | Jimmy Tygh | KO | 8 (10), 1:13 | March 3, 1941 | Philadelphia Arena, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 12 | Win | 12–0 | Gene Spencer | RTD | 4 (6) | February 27, 1941 | Olympia Stadium, Detroit, Michigan, U.S. | |

| 11 | Win | 11–0 | Bobby McIntire | UD | 6 | February 21, 1941 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 10 | Win | 10–0 | Benny Cartagena | KO | 1 (6), 1:33 | February 8, 1941 | Ridgewood Grove, Brooklyn, New York, U.S. | |

| 9 | Win | 9–0 | George Zengaras | PTS | 6 | January 31, 1941 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 8 | Win | 8–0 | Frankie Wallace | TKO | 1 (6), 2:10 | January 13, 1941 | Philadelphia Arena, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 7 | Win | 7–0 | Tony Iacovacci | KO | 1 (6), 0:40 | January 4, 1941 | Ridgewood Grove, Brooklyn, New York, U.S. | |

| 6 | Win | 6–0 | Oliver White | TKO | 3 (4) | December 13, 1940 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. | |

| 5 | Win | 5–0 | Norment Quarles | TKO | 4 (8), 0:56 | December 9, 1940 | Philadelphia Arena, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 4 | Win | 4–0 | Bobby Woods | KO | 1 (6), 1:31 | November 11, 1940 | Philadelphia Arena, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

| 3 | Win | 3–0 | Mitsos Grispos | UD | 6 | October 22, 1940 | New York Coliseum, Bronx, New York, U.S. | |

| 2 | Win | 2–0 | Silent Stafford | TKO | 2 (4) | October 8, 1940 | Municipal Auditorium, Savannah, Georgia, U.S. | |

| 1 | Win | 1–0 | Joe Echevarria | TKO | 2 (4), 0:51 | October 4, 1940 | Madison Square Garden, New York City, New York, U.S. |

Later life[edit]

In his autobiography, Robinson states that by 1965 he was broke, having spent all of the $4 million in earnings he made inside and out of the ring during his career.[59] A month after his last fight, Robinson was honored with a Sugar Ray Robinson Night on December 10, 1965, in New York's Madison Square Garden. During the ceremony, he was honored with a massive trophy. However, there was not a piece of furniture in his small Manhattan apartment with legs strong enough to support it. Robinson was elected to the Ring Magazine boxing Hall of Fame in 1967, two years after he retired and the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990. In the late 1960s he acted in some television shows, like Mission: Impossible. An episode of Land of the Giants called "Giants and All That Jazz" had Sugar as a washed up boxer opening a nightclub.[60] He also appeared in a few films including the Frank Sinatra cop movie The Detective (1968), the cult classic Candy (1968), and the thriller The Todd Killings (1971) as a police officer. In 1969, he founded the Sugar Ray Robinson Youth Foundation for the inner-city Los Angeles area. The foundation does not sponsor a boxing program.[61] He was diagnosed with diabetes mellitus that was treated with insulin.[62]

Death[edit]

In Robinson's last years he was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.[62] He died in Los Angeles on April 12, 1989 at the age of 67. Robinson is buried at Inglewood Park Cemetery, Inglewood, California.[63]

Personal life[edit]

Robinson married Marjorie Joseph in 1938; the marriage was annulled the same year. Their son, Ronnie Smith, was born in 1939. Robinson met his second wife Edna Mae Holly, a noted dancer who performed at the Cotton Club and toured Europe with Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway. According to Robinson, he met her at a local pool he frequented after his boxing workouts. In an attempt to get her attention he pushed her into the pool one day, and said it was an accident.[64] After this attempt was met with disdain, he appeared at the nightclub she danced at and introduced himself. Soon the couple were dating and they married in 1944.[65] They had one son, Ray Robinson Jr. (born 1949) before their acrimonious divorce in 1962.[66] She appeared on the first cover of Jet magazine in 1951.[67]

In April 1959, Robinson's eldest sister, Marie, died of cancer at the age of 41.[68]

In December 1959, Barbara Johnson (aka Barbara Trevigne) of South Ozone Park, a beautiful singer and dancer, brought a paternity suit in New York against the former champ, claiming Sugar Ray Robinson was the father of her son Paul born in 1953. On May 18, 1963, Jet reported that the court had ruled in Robinson's favor. Robinson is quoted exulting at the win saying "Justice triumphed."[69]

In 1965, Robinson married Millie Wiggins Bruce and the couple settled in Los Angeles.[31] When Robinson was sick with his various ailments, his son accused the elder Robinson's wife of keeping him under the influence of medication to manipulate him. According to Ray Robinson Jr., when Robinson Sr's mother died, he could not attend his mother's funeral because Millie was drugging and controlling him.[70] However, Robinson had been hospitalized the day before his mother's death due to agitation which caused his blood pressure to rise. Robinson Jr. and Edna Mae also said they were kept away from Robinson by Millie during the last years of his life.[70]

Robinson was a Freemason, a membership shared with a number of other athletes, including fellow boxer Jack Dempsey.[71][72]Robinson guest-starred in Season 2, Episode 6 of Irwin Allen's Land of the Giants.[citation needed]

Boxing style[edit]

Rhythm is everything in boxing. Every move you make starts with your heart, and that's in rhythm or you're in trouble.

— Ray Robinson[73]

Robinson was the modern definition of a boxer puncher. He was able to fight almost any style: he could come out one round brawling, the next counterpunching, and the next fighting on the outside flicking his jab. Robinson would use his formless style to exploit his opponents' weaknesses. He also possessed great speed and precision. He fought in a very conventional way with a firm jab, but threw hooks and uppercuts in flurries in an unconventional way.[74] He possessed tremendous versatility—according to boxing analyst Bert Sugar, "Robinson could deliver a knockout blow going backward."[75] Robinson was efficient with both hands, and he displayed a variety of effective punches—according to a Time article in 1951, "Robinson's repertoire, thrown with equal speed and power by either hand, includes every standard punch from a bolo to a hook—and a few he makes up on the spur of the moment."[12] Robinson commented that once a fighter has trained to a certain level, their techniques and responses become almost reflexive. "You don't think. It's all instinct. If you stop to think, you're gone."[76]

Legacy[edit]

Robinson has been ranked as one of the greatest boxers of all time by sportswriters, fellow boxers, and trainers.[11][77][78] The phrase "pound for pound" was created by sportswriters for him during his career as a way to compare boxers irrespective of weight.[13][29] Hall of Fame fighters Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis, Roberto Durán and Sugar Ray Leonard have ranked Robinson as the greatest pound-for-pound boxer in history.[75][79][80] In 1997, The Ring ranked him as the best pound-for-pound fighter in history,[13] and in 1999 he was named "welterweight of the century", "middleweight of the century", and overall "fighter of the century" by the Associated Press.[81] In 2007 ESPN.com featured the piece "50 Greatest Boxers of All Time", in which it named Robinson the top boxer in history.[77] In 2003, The Ring ranked him number 11 in the list of all-time greatest punchers.[82] Robinson was also ranked as the number 1 welterweight and the number 1 pound-for-pound boxer of all time by the International Boxing Research Organization.[83] He was inducted into the Madison Square Garden Walk of Fame at its inception in 1992.[84]

Robinson was one of the first African Americans to establish himself as a star outside sports. He was an integral part of the New York social scene in the 1940s and 1950s.[13] His glamorous restaurant, Sugar Ray's, hosted stars including Frank Sinatra, Jackie Gleason, Nat King Cole, Joe Louis, and Lena Horne.[85][86] Robinson was known as a flamboyant personality outside the ring. He combined striking good looks[87] with charisma and a flair for the dramatic. He drove a flamingo-pink Cadillac and was an accomplished singer and dancer, who once pursued a career in the entertainment industry.[88] According to ESPN's Ron Flatter: "He was the pioneer of boxing's bigger-than-life entourages, including a secretary, barber, masseur, voice coach, a coterie of trainers, beautiful women, a dwarf mascot and lifelong manager George Gainford."[13] When Robinson first traveled to Paris, a steward referred to his companions as his "entourage". Although Robinson said he did not like the word's literal definition of "attendants", since he felt they were his friends, he liked the word itself and began to use it in regular conversation when referring to them.[89] In 1962, in an effort to persuade Robinson to return to Paris—where he was still a national hero—the French promised to bring over his masseur, his hairdresser, a man who would whistle while he trained, and his trademark Cadillac.[90] This larger-than-life persona made him the idol of millions of African American youths in the 1950s. Robinson inspired several other fighters who took the nickname "Sugar" in homage to him: Sugar Ray Leonard, Sugar Shane Mosley, and MMA fighter "Suga" Rashad Evans.[91][92][93]

See also[edit]

- List of welterweight boxing champions

- List of middleweight boxing champions

- The Ring pound for pound

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ Before that fight, Robinson had a dream that he was going to accidentally kill Doyle in the ring. As a result, he decided to pull out of the fight. However, a priest and a minister convinced him to go ahead with the bout."Sugar Ray Robinson – Dreams Come True". YouTube. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Sugar Ray Robinson. International Boxing Hall of Fame.

- ^ "Sugar Ray Robinson's record". BoxRec. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ Jackson, Ron. "Most consecutive unbeaten streak". Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ^ Eisele, Andrew. "Ring Magazine's 80 Best Fighters of the Last 80 Years". About.com Sports.

- ^ "BoxRec ratings: world, pound-for-pound, active and inactive". BoxRec. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ "Sugar Ray Robinson". Biography. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ United States Postal Service Stamp Announcements

- ^ a b Robinson and Anderson, p. 7.

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, p. 5.

- ^ a b c "Sugar Ray Robinson Returns to the Ring to a 'Stamping Ovation' of 100 Million" (Press release). U.S.Postal Service. April 7, 2006. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Businessman Boxer, Time, June 25, 1951, Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Flatter, Ron. "The sugar in the sweet science". ESPN. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Schwartz, Larry. "A brooding genius". ESPN. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c Nichols, Joseph C. (November 1, 1941). Harlem Fighter Still Unbeaten, The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Dawson, James P. (January 17, 1942). "Robinson Knocks Out Zivic in Tenth Round to Score 27th Victory in Row". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Nichols, Joseph C. (October 3, 1942). "Robinson Takes Unanimous Decision Over La Motta in Garden 10-Round Bout". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c Robinson's Streak Ended by LaMotta, The New York Times, Associated Press. February 6, 1943. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, p. 110.

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, pp. 120–129.

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, pp. 126–130.

- ^ Ray Robinson, FBI. Retrieved June 6, 2007.[failed verification]

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, p. 130.

- ^ Boyd and Robinson II. pp. 94

- ^ "Sugar: Too sweet for Raging Bull". BBC News. July 13, 2001. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "The Lineal Welterwweight Champs". The Cyber Boxing Zone Encyclopedia.

- ^ Boyd and Robinson II. p. 93

- ^ Boyd and Robinson II. pp. 105–06

- ^ a b Anderson, Dave (April 13, 1989). "Sports of the Times; The Original Sugar Ray 'Never Lost'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ "Sugar Ray Robinson – Dreams Come True". YouTube. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Sugar Ray Robinson, Contemporary Black Biography, The Gale Group, 2006 ISBN 0-7876-7927-5, via Answers.com. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Robinson's biographer Wil Haygood stated during a September 25, 2010 book festival appearance that Doyle was pushing himself to fight to "buy his mother a house" and after Doyle's death in 1947, Robinson gave the earnings of his next four fights to Doyle's mother, so she could buy that house."

- ^ Wil Haygood, Book TV, September 2010

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, p. 165.

- ^ "The Lineal Middleweight Champions". The Cyber Boxing Zone Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Jake LaMotta". BoxRec. Retrieved June 6, 2007. Archived April 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, pp. 187–88.

- ^ Dethroned in London, The New York Times, July 15, 1951. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Sugar Ray Gives Mme. Auriol Kiss; Boxer as Cancer Fund 'Envoy,' Busses French Chief's Wife Twice on Each Cheek, The New York Times, May 17, 1951. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "Sugar's Lumps". Time. July 23, 1951. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Daley, Arthur (September 12, 1951). "Sports of The Times; For the Championship". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Harlem Hails Robinson; More Than 10,000 Cheer Verdict, Sing and Dance in Street, The New York Times, September 13, 1951. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Rose, Murray (December 27, 1951). "Sugar Ray Robinson Named Fighter Of Year". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "The Lineal Light Heavyweight Champions". The Cyber Boxing Zone Encyclopedia.

- ^ Robinson and Anderson. p. 227

- ^ Robinson and Anderson. p. 266

- ^ Nichols, Joseph C. (May 1, 1957). "Utah 160-Pounder to Defend Crown". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Nichols, Joseph C. (May 2, 1957). "Robinson Knocks Out Fullmer in Fifth Round to Regain Middleweight Crown". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Fitzgerald and Hudson. p. 40

*Gene Fullmer, ibhof.com. Retrieved June 6, 2007. Archived December 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine - ^ "Basilio Takes Title By Beating Robinson". The New York Times. September 24, 1957. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Nichols, Joseph C. (March 26, 1958). "Robinson Outpoints Basilio and Wins World Middleweight Title Fifth Time". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Nichols, Joseph C. (January 23, 1960). "5–1 Choice Loses A Split Decision", The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Conkilin, William R. (October 22, 1961) "Robinson Beats Moyer in Ten-Rounder Here". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Teague, Robert L. (February 18, 1962). "Denny Moyer Defeats Robinson". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b Left Hook Floors Sugar Ray in 4th, The New York Times, June 25, 1963. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b "Robinson Beaten in Archer Fight". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 11, 1965. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "Robinson Declares Bout With Archer Was His Last Fight". The New York Times. Associated Press. November 12, 1965. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/Jimmy_Doyle

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, p. 4.

- ^ Mission Impossible Archived October 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ^ Wiley. p. 223

- ^ a b Pace, Frank (August 1976). "Keeping Pace with Sugar Ray Robinson". LA Sports Magazine. Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved June 5, 2007 – via Hall of Fame Magazine.

- ^ "Sugar Ray Robinson". Find a Grave. November 6, 1998. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, pp. 91–2.

- ^ Wiley, Ralph (July 13, 1987). "Bittersweet Twilight for Sugar". Sports Illustrated Vault.

- ^ "Remembering Sugar Ray: Edna Mae Robinson recalls the glitter and pain of her past". Ebony. XLV (2): 74, 76, 78. December 1989.

- ^ Chenault. p. 31

- ^ "Ray Robinson's' Sister Dies". The New York Times, April 21, 1959. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "Sugar Beats Paternity Suit On His 40th Birthday". Jet. XX (4): 54. May 18, 1961. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Wiley. p. 221

- ^ "Famous Free Masons: Athletes". U.S. News & World Report. May 14, 2013. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Well Known Freemasons". Grand Lodge of British Columbia A.F. & A. M. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, p. 75.

- ^ Boyd and Robinson II. p. 271

- ^ a b Sugar Ray Robinson quotes, cgmworldwide.com. Retrieved June 6, 2007. Archived October 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hauser. p. 29

- ^ a b Mulvaney, Kieran. Who's the Greatest?, ESPN. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- ^ Sugar Ray Bio Archived November 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, cgmworldwide.com. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

*Review Joe and Teddy Pick Their Top Fighters[dead link], espn.com. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

* Smith, Michael David (May 13, 2007). ESPN Greatest Boxers List: Sugar Ray Robinson No. 1 Archived June 3, 2012, at archive.today, AOL News. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

* Wiley. p. 226

*Anderson, Dave (April 13, 1989). "Sugar Ray Robinson, Boxing's 'Best,' Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

* Trickett, Alex, and Dirs, Ben. Who is the greatest of them all?, bbc.co.uk, June 13, 2005. Retrieved June 6, 2007."Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 4, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Kehoe, Patrick. Ray Robinson: The champions' champion Archived December 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. secondsout.com. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ^ Hauser. p. 212

- ^ Sugar Ray named century's best, ESPN, Associated Press. December 8, 1999. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ Ring Magazine's 100 Greatest Punchers, The Ring, (2003), available online at about.com. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "IBRO Rankings". Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Madison Square Garden Gets Walk Of Fame". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. September 12, 1992. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Boyd and Robinson II. p. 105

- ^ Kilgannon, Corey (November 25, 2009). "Sugar Ray's Harlem: Back in the Day". The New York Times. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- ^ Goldman, Albert (October 8, 1968). "Sugar Ray: Is He a Black Gable?". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

* Sammons. p. xii

*"The Man Who Comes Back". Time, April 7, 1958. Retrieved June 6, 2007. - ^ Fitzgerald and Hudson. pp. 205–06

- ^ Robinson and Anderson, p. 169.

- ^ Daley, Robert (May 13, 1962). "Sugar Ray Is Still Young in Paris; Age Hasn't Dimmed Robinson's Skills in Frenchmen's Eyes". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (June 18, 1980). "For Some People there is only One Sugar Ray". The New York Times. Retrieved August 24, 2010 – via The Miami News.[dead link]

- ^ Schuyler, Ed (September 21, 1998). Article: Sugar Shane wants to look sweet for Sugar Ray, Associated Press. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ Iole, Kevin (September 6, 2008). "Few pegged Rashad Evans' main-event status". MMAjunkie.com. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

Sources[edit]

- Boyd, Herb, and Robinson, Ray II. Pound for Pound: A Biography of Sugar Ray Robinson, New York: HarperCollins, 2005 ISBN 0-06-018876-6

- Chenault, Julie. Edna Mae Robinson Still Looking Good in Her Mink. Jet, Johnson Publishing Company November 5, 1981 issue ISSN 0021-5996 (available online)

- Donelson, Thomas, and Lotierzo, Frank. Viewing Boxing from Ringside, Lincoln: iUniverse, 2002 ISBN 0-595-23748-7

- Fitzgerald, Mike H., and Hudson, Dabid L. Boxing's Most Wanted: The Top Ten Book of Champs, Chumps and Punch-drunk Palookas, Virginia: Brassey's, 2004 ISBN 1-57488-714-9

- Hauser, Thomas. The Black Lights: Inside the World of Professional Boxing, Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000 ISBN 1-55728-597-7

- Nagler, Barney. "Boxing's Bad Boy: Sugar Ray Robinson". SPORT Magazine. October 1947.

- Robinson, Sugar Ray, and Anderson, Dave. Sugar Ray, London: Da Capo Press, 1994 ISBN 0-306-80574-X

- Sammons, Jeffrey Thomas. Beyond the Ring: The Role of Boxing in American Society, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998 ISBN 0-252-06145-4

- Wiley, Ralph. Serenity: A Boxing Memoir, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000 ISBN 0-8032-9816-1

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sugar Ray Robinson. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sugar Ray Robinson |

- Boxing record for Sugar Ray Robinson from BoxRec

- Official website

| Sporting positions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World titles | ||||

| Preceded by Marty Servo Vacated | World Welterweight champion December 20, 1946 – December 25, 1950 Vacated | Vacant Title next held by Kid Gavilán | ||

| Preceded by Jake LaMotta | World Middleweight champion January 14, 1951 – July 10, 1951 | Succeeded by Randy Turpin | ||

| Preceded by Randy Turpin | World Middleweight champion September 12, 1951 – December 1952 Retired | Vacant Title next held by Carl Olson | ||

| Preceded by Carl Olson | World Middleweight champion May 18, 1956 – January 2, 1957 | Succeeded by Gene Fullmer | ||

| Preceded by Gene Fullmer | World Middleweight champion May 1, 1957 – September 23, 1957 | Succeeded by Carmen Basilio | ||

| Preceded by Carmen Basilio | NBA Middleweight champion March 25, 1958 – 1959 Stripped | Vacant Title next held by Gene Fullmer | ||

| World Middleweight champion March 25, 1958 – January 2, 1960 | Succeeded by Paul Pender | |||

| Records | ||||

| Preceded by Stanley Ketchel 2 | Most world title reigns in middleweight division 5 March 25, 1958 – present | Incumbent | ||

- Sugar Ray Robinson Biography – Fightfanatics.com

- Image of Sugar Ray Robinson after bout with Carl (Bobo) Olson, Los Angeles, 1956. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

- Image of Sugar Ray Robinson receives physical exam before fight, Los Angeles, 1956. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

- https://www.nytimes.com/1959/05/05/archives/national-boxing-association-strips-robinson-of-world-middleweight.html

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1947

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1948

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1949

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1950

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1951

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1952

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1955

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1956

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1957

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1958

- https://boxrec.com/media/index.php/National_Boxing_Association%27s_Quarterly_Ratings:_1959