| Jimi Hendrix | |

|---|---|

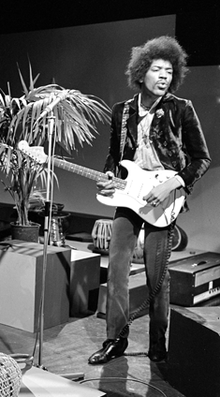

Hendrix actuando en el programa de televisión holandés Hoepla en 1967 | |

| Información de contexto | |

| Nombre de nacimiento | Johnny Allen Hendrix |

| Nació | 27 de noviembre de 1942 Seattle, Washington , EE. UU. |

| Fallecido | 18 de septiembre de 1970 (27 años) Kensington , Londres, Inglaterra |

| Géneros | |

| Ocupación (es) |

|

| Instrumentos |

|

| Años activos | 1963-1970 |

| Etiquetas | |

| Actos asociados |

|

| Sitio web | jimihendrix |

James Marshall " Jimi " Hendrix (nacido como Johnny Allen Hendrix ; 27 de noviembre de 1942 - 18 de septiembre de 1970) fue un músico, cantante y compositor estadounidense. Aunque su carrera en la corriente principal duró solo cuatro años, es ampliamente considerado como uno de los guitarristas eléctricos más influyentes en la historia de la música popular y uno de los músicos más célebres del siglo XX. El Salón de la Fama del Rock and Roll lo describe como "posiblemente el más grande instrumentista en la historia de la música rock". [1]

Nacido en Seattle , Washington, Hendrix comenzó a tocar la guitarra a la edad de 15 años. En 1961, se alistó en el ejército de los Estados Unidos, pero fue dado de baja al año siguiente. Poco después, se mudó a Clarksville, Tennessee , y comenzó a tocar en el circuito chitlin ' , ganándose un lugar en la banda de apoyo de los Isley Brothers y más tarde con Little Richard , con quien continuó trabajando hasta mediados de 1965. Luego tocó con Curtis Knight and the Squires antes de mudarse a Inglaterra a fines de 1966 después de que el bajista Chas Chandler of the Animals se convirtiera en su manager. En unos meses, Hendrix había obtenido tres éxitos entre los diez primeros del Reino Unido con la experiencia Jimi Hendrix: "Hey Joe "," Purple Haze "y" The Wind Cries Mary ". Alcanzó la fama en los Estados Unidos después de su actuación en el Monterey Pop Festival en 1967, y en 1968 su tercer y último álbum de estudio, Electric Ladyland , alcanzó el número uno. en los Estados Unidos. El LP doble fue el lanzamiento más exitoso comercialmente de Hendrix y su primer y único álbum número uno. El artista mejor pagado del mundo, [2] encabezó el Festival de Woodstock en 1969 y el Festival de la Isla de Wight en 1970 antes de su accidental Muerte en Londres por asfixia relacionada con barbitúricos el 18 de septiembre de 1970.

Hendrix se inspiró en el rock and roll estadounidense y el blues eléctrico . Él favoreció los amplificadores saturados con alto volumen y ganancia , y fue fundamental en la popularización de los sonidos previamente indeseables causados por la retroalimentación del amplificador de guitarra . También fue uno de los primeros guitarristas en hacer un uso extensivo de las unidades de efectos que alteran el tono en el rock convencional, como la distorsión fuzz, Octavia , wah-wah y Uni-Vibe . Fue el primer músico en utilizar efectos de fase estereofónicos en las grabaciones. Holly George-Warren de Rolling Stonecomentó: "Hendrix fue pionero en el uso del instrumento como fuente de sonido electrónico. Los jugadores antes que él habían experimentado con la retroalimentación y la distorsión, pero Hendrix convirtió esos efectos y otros en un vocabulario fluido y controlado tan personal como el blues con el que comenzó. . " [3]

Hendrix recibió varios premios musicales durante su vida y a título póstumo. En 1967, los lectores de Melody Maker lo votaron como el Músico pop del año y en 1968, Billboard lo nombró Artista del año y Rolling Stone lo nombró Artista del año. Disc and Music Echo lo honró con el Mejor Músico Mundial de 1969 y en 1970, Guitar Player lo nombró Guitarrista de Rock del Año. The Jimi Hendrix Experience fue incluido en el Salón de la Fama del Rock and Roll en 1992 y en el Salón de la Fama de la Música del Reino Unido en 2005. Rolling Stone clasificó los tres álbumes de estudio de la banda, Are You Experienced ,Axis: Bold as Love y Electric Ladyland , entre los 100 mejores álbumes de todos los tiempos , y clasificaron a Hendrix como el mejor guitarrista y el sexto mejor artista de todos los tiempos.

Ascendencia e infancia

La genealogía mixta de Jimi Hendrix incluía antepasados afroamericanos , irlandeses y cherokee . Su abuela paterna, Zenora "Nora" Rose Moore, era afroamericana y un cuarto de cherokee. [4] [nb 1] El abuelo paterno de Hendrix, Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix (nacido en 1866), nació de una relación extramarital entre una mujer llamada Fanny y un comerciante de cereales de Urbana, Ohio o Illinois, uno de los hombres más ricos de el área en ese momento. [7] [8] [nb 2] Después de que Hendrix y Moore se mudaron a Vancouver, tuvieron un hijo al que llamaron James Allen Hendrix el 10 de junio de 1919; la familia lo llamaba "Al". [10]

En 1941, después de mudarse a Seattle , Al conoció a Lucille Jeter (1925-1958) en un baile; se casaron el 31 de marzo de 1942. [11] El padre de Lucille (el abuelo materno de Jimi) era Preston Jeter (nacido en 1875), cuya madre nació en circunstancias similares a las de Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix. [12] La madre de Lucille, de soltera Clarice Lawson, tenía antepasados afroamericanos y cherokee. [13] Al, quien había sido reclutado por el ejército de los Estados Unidos para servir en la Segunda Guerra Mundial , se fue para comenzar su entrenamiento básico tres días después de la boda. [14]Johnny Allen Hendrix nació el 27 de noviembre de 1942 en Seattle; fue el primero de los cinco hijos de Lucille. En 1946, los padres de Johnny cambiaron su nombre a James Marshall Hendrix, en honor a Al y su difunto hermano Leon Marshall. [15] [nb 3]

Estacionado en Alabama en el momento del nacimiento de Hendrix, a Al se le negó el permiso militar estándar otorgado a los militares para el parto; su oficial al mando lo colocó en la empalizada para evitar que se ausentara para ver a su hijo pequeño en Seattle. Pasó dos meses encerrado sin juicio, y mientras estaba en la empalizada recibió un telegrama anunciando el nacimiento de su hijo. [17] [nb 4] Durante los tres años de ausencia de Al, Lucille luchó por criar a su hijo. [19] Cuando Al estaba fuera, los familiares y amigos cuidaban principalmente de Hendrix, especialmente la hermana de Lucille, Delores Hall y su amiga Dorothy Harding. [20] Al recibió una baja honorabledel Ejército de los Estados Unidos el 1 de septiembre de 1945. Dos meses después, sin poder encontrar a Lucille, Al fue a Berkeley, California , a la casa de una amiga de la familia llamada Sra. Champ, que se había ocupado de Hendrix y había intentado adoptarla; aquí es donde Al vio a su hijo por primera vez. [21]

Después de regresar del servicio, Al se reunió con Lucille, pero su incapacidad para encontrar un trabajo estable dejó a la familia empobrecida. Ambos lucharon contra el alcohol y, a menudo, lucharon cuando estaban intoxicados. La violencia a veces llevó a Hendrix a retirarse y esconderse en un armario en su casa. [22] Su relación con su hermano León (nacido en 1948) era estrecha pero precaria; con León entrando y saliendo del cuidado de crianza, vivían con una amenaza casi constante de separación fraterna. [23] Además de Leon, Hendrix tenía tres hermanos menores: Joseph, nacido en 1949, Kathy en 1950 y Pamela, 1951, todos los cuales Al y Lucille entregaron al cuidado de crianza y la adopción. [24]La familia se mudó con frecuencia, alojándose en hoteles y apartamentos baratos en Seattle. En ocasiones, miembros de la familia llevaban a Hendrix a Vancouver para quedarse en casa de su abuela. Un niño tímido y sensible, fue profundamente afectado por sus experiencias de vida. [25] En años posteriores, le confió a una novia que había sido víctima de abuso sexual por parte de un hombre de uniforme. [26] El 17 de diciembre de 1951, cuando Hendrix tenía nueve años, sus padres se divorciaron; el tribunal le otorgó a Al la custodia de él y León. [27]

Primeros instrumentos

En la Escuela Primaria Horace Mann en Seattle a mediados de la década de 1950, el hábito de Hendrix de llevar una escoba con él para emular una guitarra llamó la atención del trabajador social de la escuela. Después de más de un año de que él se aferrara a una escoba como una manta de seguridad , ella escribió una carta solicitando fondos escolares destinados a niños desfavorecidos, insistiendo en que dejarlo sin una guitarra podría resultar en daño psicológico. [28] Sus esfuerzos fracasaron y Al se negó a comprarle una guitarra. [28] [nb 5]

En 1957, mientras ayudaba a su padre con un trabajo secundario, Hendrix encontró un ukelele entre la basura que estaban sacando de la casa de una mujer mayor. Ella le dijo que podía quedarse con el instrumento, que solo tenía una cuerda. [30] Aprendiendo de oído, tocó notas individuales, siguiendo las canciones de Elvis Presley , particularmente " Hound Dog ". [31] [nb 6] A la edad de 33 años, la madre de Hendrix, Lucille, había desarrollado cirrosis hepática y el 2 de febrero de 1958 murió cuando se le rompió el bazo . [33]Al se negó a llevar a James y Leon para asistir al funeral de su madre; en cambio, les dio tragos de whisky y les indicó que así es como los hombres deben lidiar con la pérdida. [33] [nb 7] En 1958, Hendrix completó sus estudios en Washington Junior High School y comenzó a asistir, pero no se graduó, Garfield High School . [34] [nb 8]

A mediados de 1958, a los 15 años, Hendrix adquirió su primera guitarra acústica por $ 5 [37] (equivalente a $ 44 en 2019). Tocaba durante horas todos los días, observando a otros y aprendiendo de guitarristas más experimentados, y escuchando a artistas de blues como Muddy Waters , BB King , Howlin 'Wolf y Robert Johnson . [38] La primera melodía que aprendió a tocar Hendrix fue el tema de televisión " Peter Gunn ". [39] Alrededor de ese tiempo, Hendrix improvisó con su amigo de la infancia Sammy Drain y su hermano que tocaba el teclado. [40] En 1959, asistiendo a un concierto de Hank Ballard & the Midnightersen Seattle, Hendrix conoció al guitarrista del grupo Billy Davis . [41] Davis le mostró algunos toques de guitarra y le consiguió un breve concierto con los Midnighters. [42] Los dos siguieron siendo amigos hasta la muerte de Hendrix en 1970. [43]

Poco después de adquirir la guitarra acústica, Hendrix formó su primera banda, los Velvetones. Sin una guitarra eléctrica, apenas se le podía escuchar por encima del sonido del grupo. Después de unos tres meses, se dio cuenta de que necesitaba una guitarra eléctrica. [44] A mediados de 1959, su padre cedió y le compró un Supro Ozark blanco . [44] El primer concierto de Hendrix fue con una banda anónima en el Jaffe Room del Temple De Hirsch de Seattle , pero lo despidieron entre sets por lucirse. [45] Se unió a los Rocking Kings, que jugaban profesionalmente en lugares como el club Birdland. Cuando le robaron la guitarra después de dejarla detrás del escenario durante la noche, Al le compró un Danelectro plateado rojo .[46]

Servicio militar

Antes de que Hendrix tuviera 19 años, las autoridades legales lo habían atrapado dos veces en autos robados . Cuando se le dio a elegir entre la prisión o unirse al ejército , eligió este último y se alistó el 31 de mayo de 1961. [47] Después de completar ocho semanas de entrenamiento básico en Fort Ord , California, fue asignado a la 101a División Aerotransportada y estacionado en Fort Campbell , Kentucky. [48] Llegó el 8 de noviembre, y poco después le escribió a su padre: "No hay nada más que entrenamiento físico y acoso aquí durante dos semanas, luego cuando vas a la escuela de salto ... te vas al infierno. Te trabajan hasta la muerte , quejándose y peleando." [49]En su siguiente carta a casa, Hendrix, que había dejado su guitarra en Seattle en la casa de su novia Betty Jean Morgan, le pidió a su padre que se la enviara lo antes posible, diciendo: "Realmente la necesito ahora". [49] Su padre obedeció y envió el Danelectro plateado rojo en el que Hendrix había pintado a mano las palabras "Betty Jean" a Fort Campbell. [50] Su aparente obsesión por el instrumento contribuyó a que descuidara sus deberes, lo que provocó burlas y abusos físicos por parte de sus compañeros, quienes al menos una vez le ocultaron la guitarra hasta que suplicó que se la devolviera. [51] En noviembre de 1961, su compañero Billy Cox pasó junto a un club del ejército y escuchó a Hendrix tocar. [52]Impresionado por la técnica de Hendrix, que Cox describió como una combinación de " John Lee Hooker y Beethoven ", Cox tomó prestado un bajo y los dos tocaron . [53] En cuestión de semanas, comenzaron a actuar en clubes de base los fines de semana con otros músicos en una banda poco organizada, The Casuals. [54]

Hendrix completó su entrenamiento de paracaidista en poco más de ocho meses, y el mayor general CWG Rich le otorgó el prestigioso parche Screaming Eagles el 11 de enero de 1962. [49] En febrero, su conducta personal había comenzado a generar críticas de sus superiores. Lo etiquetaron como un tirador no calificado y, a menudo, lo sorprendieron durmiendo una siesta mientras estaba de servicio y no se presentó a los controles de cama. [55] El 24 de mayo, el sargento de pelotón de Hendrix, James C. Spears, presentó un informe en el que decía: "No tiene ningún interés en el Ejército ... En mi opinión, el soldado Hendrix nunca llegará a los estándares requerido de un soldado. Creo que el servicio militar se beneficiará si es dado de baja lo antes posible ". [56]El 29 de junio de 1962, a Hendrix se le concedió la baja general en condiciones honorables . [57] Hendrix luego habló de su disgusto por el ejército y mintió que había recibido un alta médica después de romperse el tobillo durante su 26º salto en paracaídas. [58] [nb 9]

Carrera profesional

Primeros años

En septiembre de 1963, después de que Cox fuera dado de baja del ejército, él y Hendrix se trasladaron unas 20 millas (32 km) a través de la línea estatal desde Fort Campbell hasta Clarksville, Tennessee , y formaron una banda, los King Kasuals. [60] En Seattle, Hendrix vio a Butch Snipes tocar con los dientes y ahora el segundo guitarrista de Kasual, Alphonso "Baby Boo" Young, estaba realizando este truco de guitarra. [61] Para no quedar eclipsado, Hendrix también aprendió a tocar de esta manera. Más tarde explicó: "Se me ocurrió la idea de hacer eso ... en Tennessee. Allí abajo tienes que jugar con los dientes o te disparan. Hay un rastro de dientes rotos por todo el escenario". [62]

Aunque empezaron a tocar en conciertos con salarios bajos en lugares desconocidos, la banda finalmente se mudó a Jefferson Street en Nashville , que era el corazón tradicional de la comunidad negra de la ciudad y hogar de una próspera escena musical de rhythm and blues . [63] Obtuvieron una breve residencia tocando en un lugar popular de la ciudad, el Club del Marruecos, y durante los dos años siguientes Hendrix se ganó la vida actuando en un circuito de lugares en todo el sur que estaban afiliados a la Asociación de Reservas de Propietarios de Teatros. (TOBA), ampliamente conocido como el circuito chitlin ' . [64] Además de tocar en su propia banda, Hendrix actuó como músico de acompañamiento para varios músicos de soul, R&B y blues, incluidosWilson Pickett , Slim Harpo , Sam Cooke , Ike y Tina Turner [65] y Jackie Wilson . [66]

En enero de 1964, sintiendo que había superado el circuito artísticamente y frustrado por tener que seguir las reglas de los líderes de banda, Hendrix decidió aventurarse por su cuenta. Se mudó al Hotel Theresa en Harlem , donde se hizo amigo de Lithofayne Pridgon, conocida como "Faye", quien se convirtió en su novia. [67] Originario de Harlem con conexiones en toda la escena musical de la zona, Pridgon le proporcionó refugio, apoyo y aliento. [68] Hendrix también conoció a los gemelos Allen, Arthur y Albert. [69] [nb 10] En febrero de 1964, Hendrix ganó el primer premio en el concurso de aficionados del Teatro Apollo . [71]Con la esperanza de asegurarse una oportunidad profesional, tocó en el circuito de clubes de Harlem y se sentó con varias bandas. Por recomendación de un ex asociado de Joe Tex , Ronnie Isley le concedió a Hendrix una audición que lo llevó a una oferta para convertirse en el guitarrista de la banda de apoyo de los Isley Brothers , los IB Specials, que aceptó de inmediato. [72]

Primeras grabaciones

En marzo de 1964, Hendrix grabó el sencillo de dos partes " Testify " con los Isley Brothers. Lanzado en junio, no se trazó. [73] En mayo, proporcionó la instrumentación de guitarra para la canción de Don Covay , " Mercy Mercy ". Publicado en agosto por Rosemart Records y distribuido por Atlantic , la pista alcanzó el puesto 35 en la lista de Billboard . [74]

Hendrix estuvo de gira con los Isleys durante gran parte de 1964, pero a finales de octubre, después de cansarse de tocar el mismo set todas las noches, dejó la banda. [75] [nb 11] Poco después, Hendrix se unió a la banda de gira de Little Richard , los Upsetters . [77] Durante una parada en Los Ángeles en febrero de 1965, grabó su primer y único sencillo con Richard, "I Don't Know What You Got (But It's Got Me)", escrito por Don Covay y publicado por Vee-Jay. Registros . [78] La popularidad de Richard estaba disminuyendo en ese momento, y el single alcanzó el puesto 92, donde permaneció durante una semana antes de caer de la lista. [79] [nb 12]Hendrix conoció a la cantante Rosa Lee Brooks mientras se hospedaba en el hotel Wilcox en Hollywood, y ella lo invitó a participar en una sesión de grabación de su sencillo, que incluía a Arthur Lee escrito "My Diary" como cara A y "Utee" como el lado B. [81] Hendrix tocó la guitarra en ambas pistas, que también incluyó la voz de fondo de Lee. El sencillo no llegó a las listas, pero Hendrix y Lee comenzaron una amistad que duró varios años; Más tarde, Hendrix se convirtió en un ferviente partidario de la banda de Lee, Love . [81]

En julio de 1965, Hendrix hizo su primera aparición en televisión en el tren nocturno Channel 5 de Nashville . Actuando en la banda de conjunto de Little Richard, acompañó a los vocalistas Buddy y Stacy en " Shotgun ". La grabación de video del programa marca las primeras imágenes conocidas de la actuación de Hendrix. [77] Richard y Hendrix a menudo se enfrentaban por la tardanza, el vestuario y las payasadas de Hendrix en el escenario, ya finales de julio, el hermano de Richard, Robert, lo despidió. [82] El 27 de julio, Hendrix firmó su primer contrato de grabación con Juggy Murray en Sue Records y Copa Management. [83] [84]Luego se reincorporó brevemente a los Isley Brothers y grabó un segundo sencillo con ellos, "Move Over and Let Me Dance" respaldado con "Have You Ever Been Disapjected". [85] Más tarde ese año, se unió a una banda de R&B con sede en Nueva York, Curtis Knight and the Squires, después de conocer a Knight en el vestíbulo de un hotel donde se alojaban ambos hombres. [86] Hendrix actuó con ellos durante ocho meses. [87] En octubre de 1965, él y Knight grabaron el sencillo "How Would You Feel" con el respaldo de "Welcome Home". A pesar de su contrato de dos años con Sue, [88] Hendrix firmó un contrato de grabación de tres años con el empresario Ed Chalpin el 15 de octubre. [89]Si bien la relación con Chalpin fue de corta duración, su contrato se mantuvo en vigor, lo que más tarde causó problemas legales y profesionales para Hendrix. [90] [nb 13] Durante su tiempo con Knight, Hendrix realizó una breve gira con Joey Dee y los Starliters , y trabajó con King Curtis en varias grabaciones, incluido el sencillo de dos partes de Ray Sharpe , "Help Me". [92] Hendrix obtuvo sus primeros créditos como compositor por dos temas instrumentales, "Hornets Nest" y "Knock Yourself Out", lanzados como un sencillo de Curtis Knight y Squires en 1966. [93] [nb 14]

Sintiéndose restringido por sus experiencias como acompañante de R&B, Hendrix se mudó en 1966 al Greenwich Village de Nueva York , que tenía una escena musical vibrante y diversa. [98] Allí, le ofrecieron una residencia en el Café Wha? en MacDougal Street y formó su propia banda en junio, Jimmy James and the Blue Flames , que incluía al futuro guitarrista de Spirit , Randy California . [99] [nb 15] The Blue Flames tocaron en varios clubes de Nueva York y Hendrix comenzó a desarrollar su estilo y material de guitarra que pronto usaría con The Experience. [101] [102] En septiembre, dieron algunos de sus últimos conciertos en elCafe au Go Go , como el grupo de apoyo de John Hammond Jr. [103] [nb 16]

La experiencia Jimi Hendrix

En mayo de 1966, Hendrix estaba luchando por ganarse la vida jugando en el circuito de R&B, por lo que se reunió brevemente con Curtis Knight and the Squires para un compromiso en uno de los locales nocturnos más populares de la ciudad de Nueva York, el Cheetah Club. [104] Durante una actuación, Linda Keith, la novia del guitarrista de los Rolling Stones Keith Richards , notó a Hendrix y quedó "hipnotizada" por su forma de tocar. [104] Ella lo invitó a tomar una copa con ella, y los dos se hicieron amigos. [104]

Mientras Hendrix tocaba con Jimmy James y los Blue Flames, Keith lo recomendó al manager de los Stones, Andrew Loog Oldham, y al productor Seymour Stein . No vieron el potencial musical de Hendrix y lo rechazaron. [105] Keith lo refirió a Chas Chandler , quien dejaba los Animals y estaba interesado en la gestión y producción de artistas. [106] Chandler vio a Hendrix tocar en Cafe Wha? , un club nocturno de Greenwich Village , Nueva York. [106] A Chandler le gustó la canción de Billy Roberts " Hey Joe ", y estaba convencido de que podía crear un sencillo exitoso con el artista adecuado.[107] Impresionado con la versión de Hendrix de la canción, lo llevó a Londres el 24 de septiembre de 1966, [108] y lo firmó con un contrato de administración y producción con él y el ex-manager de Animals, Michael Jeffery . [109] Esa noche, Hendrix dio una actuación en solitario improvisada en The Scotch of St James y comenzó una relación con Kathy Etchingham que duró dos años y medio. [110] [nb 17]

Tras la llegada de Hendrix a Londres, Chandler comenzó a reclutar miembros para una banda diseñada para resaltar sus talentos, la Experiencia Jimi Hendrix. [112] Hendrix conoció al guitarrista Noel Redding en una audición para New Animals, donde el conocimiento de Redding sobre las progresiones del blues impresionó a Hendrix, quien declaró que también le gustaba el peinado de Redding. [113] Chandler le preguntó a Redding si quería tocar el bajo en la banda de Hendrix; Redding estuvo de acuerdo. [113] Chandler empezó a buscar un baterista y poco después se puso en contacto con Mitch Mitchell a través de un amigo en común. Mitchell, quien había sido despedido recientemente de Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, participó en un ensayo con Redding y Hendrix donde encontraron puntos en común en su interés compartido por el ritmo y el blues. Cuando Chandler llamó a Mitchell ese mismo día para ofrecerle el puesto, aceptó de inmediato. [114] Chandler también convenció a Hendrix de cambiar la ortografía de su primer nombre de Jimmy por el más exótico Jimi . [115]

El 1 de octubre de 1966, Chandler llevó a Hendrix al London Polytechnic en Regent Street, donde estaba previsto que actuara Cream , y donde se conocieron Hendrix y el guitarrista Eric Clapton . [116] Clapton dijo más tarde: "Me preguntó si podía tocar un par de números. Le dije: 'Por supuesto', pero tenía un sentimiento extraño sobre él". [112] A mitad del set de Cream, Hendrix subió al escenario e interpretó una versión frenética de la canción de Howlin 'Wolf " Killing Floor ". [112]En 1989, Clapton describió la actuación: "Tocó casi todos los estilos que puedas imaginar, y no de una manera llamativa. Quiero decir que hizo algunos de sus trucos, como jugar con los dientes y a sus espaldas, pero no fue en un sentido eclipsado en absoluto, y eso fue todo ... Se fue, y mi vida nunca volvió a ser la misma ". [112]

Éxito en el Reino Unido

A mediados de octubre de 1966, Chandler organizó un compromiso para The Experience como acto secundario de Johnny Hallyday durante una breve gira por Francia. [115] Así, Jimi Hendrix Experience realizó su primer espectáculo el 13 de octubre de 1966 en el Novelty de Evreux . [117] Su entusiasta actuación de 15 minutos en el teatro Olympia de París el 18 de octubre marca la primera grabación conocida de la banda. [115] A fines de octubre, Kit Lambert y Chris Stamp , gerentes de The Who , firmaron The Experience con su sello recién formado, Track Records., y el grupo grabó su primera canción, "Hey Joe", el 23 de octubre. [118] " Stone Free ", que fue el primer esfuerzo de composición de Hendrix después de llegar a Inglaterra, se grabó el 2 de noviembre. [119]

A mediados de noviembre, actuaron en el club nocturno Bag O'Nails en Londres, con la asistencia de Clapton, John Lennon , Paul McCartney , Jeff Beck , Pete Townshend , Brian Jones , Mick Jagger y Kevin Ayers . [120] Ayers describió la reacción de la multitud como asombrada incredulidad: "Todas las estrellas estaban allí, y escuché comentarios serios, ya sabes 'mierda', 'Jesús', 'maldición' y otras palabras peores que eso". [120] La actuación le valió a Hendrix su primera entrevista, publicada en Record Mirror con el titular: "Mr. Phenomenon". [120]"Ahora escuche esto ... predecimos que [Hendrix] va a girar alrededor del negocio como un tornado", escribió Bill Harry , quien hizo la pregunta retórica: "¿Es ese sonido pleno, grande y oscilante realmente creado por solo tres ¿personas?" [121] Hendrix dijo: "No queremos ser clasificados en ninguna categoría ... Si debe tener una etiqueta, me gustaría que se llamara 'Free Feeling'. Es una mezcla de rock, freak- out, rave y blues ". [122] A través de un acuerdo de distribución con Polydor Records , el primer sencillo de Experience, "Hey Joe", respaldado por "Stone Free", fue lanzado el 16 de diciembre de 1966. [123] Después de apariciones en los programas de televisión del Reino Unido Ready Steady Go!y el Top of the Pops, "Hey Joe" entró en las listas del Reino Unido el 29 de diciembre y alcanzó el puesto número seis. [124] Más éxito llegó en marzo de 1967 con el éxito número tres del Reino Unido " Purple Haze ", y en mayo con " The Wind Cries Mary ", que permaneció en las listas británicas durante once semanas, alcanzando el número seis. [125] El 12 de marzo de 1967, actuó en el Hotel Troutbeck, Ilkley, West Yorkshire, donde, después de que aparecieran unas 900 personas (el hotel tenía licencia para 250), la policía local detuvo el concierto por motivos de seguridad. [126]

El 31 de marzo de 1967, mientras The Experience esperaba para presentarse en el London Astoria , Hendrix y Chandler discutieron formas en las que podrían aumentar la exposición de la banda en los medios. Cuando Chandler le pidió consejo al periodista Keith Altham, Altham sugirió que necesitaban hacer algo más dramático que el espectáculo teatral de The Who, que implicaba destrozar instrumentos. Hendrix bromeó: "Tal vez pueda aplastar un elefante", a lo que Altham respondió: "Bueno, es una lástima que no puedas prender fuego a tu guitarra". [127] Chandler luego le pidió al gerente de ruta, Gerry Stickells, que le comprara un líquido para encendedor.. Durante el espectáculo, Hendrix dio una actuación especialmente dinámica antes de prender fuego a su guitarra al final de un set de 45 minutos. A raíz del truco, los miembros de la prensa de Londres etiquetaron a Hendrix como el "Elvis negro" y el "Hombre salvaje de Borneo". [128] [nb 18]

¿Tienes experiencia?

Después del éxito en las listas británicas de sus dos primeros sencillos, "Hey Joe" y "Purple Haze", The Experience comenzó a reunir material para un LP de larga duración. [130] En Londres, la grabación comenzó en De Lane Lea Studios y luego se trasladó a los prestigiosos Olympic Studios . [130] El álbum Are You Experienced presenta una diversidad de estilos musicales, incluyendo temas de blues como " Red House " y " Highway Chile ", y la canción de R&B "Remember". [131] También incluyó la pieza experimental de ciencia ficción, "La tercera piedra del sol ".y los paisajes sonoros posmodernos de la pista principal , con prominentesguitarra y batería al revés . [132] "I Don't Live Today" sirvió como medio para la improvisación de retroalimentación de guitarra de Hendrix y " Fire " fue impulsado por la batería de Mitchell. [130]

Lanzado en el Reino Unido el 12 de mayo de 1967, Are You Experienced pasó 33 semanas en las listas de éxitos, alcanzando el número dos. [133] [nb 19] El sargento de los Beatles le impidió alcanzar el primer puesto . Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band . [135] [nb 20] El 4 de junio de 1967, Hendrix abrió un espectáculo en el Saville Theatre de Londres con su interpretación de Sgt. La canción principal de Pepper , que fue lanzada apenas tres días antes. El mánager de los Beatles, Brian Epstein, era dueño del Saville en ese momento, y tanto George Harrisony Paul McCartney asistieron a la función. McCartney describió el momento: "Las cortinas se abrieron y él se acercó caminando hacia el 'Sgt. Pepper'. Es un cumplido bastante importante en el libro de cualquiera. Lo escribo como uno de los grandes honores de mi carrera". [136] Lanzado en los Estados Unidos el 23 de agosto por Reprise Records , Are You Experienced alcanzó el número cinco en el Billboard 200 . [137] [nb 21]

En 1989, Noe Goldwasser, el editor fundador de Guitar World , describió Are You Experienced como "el álbum que sacudió al mundo ... dejándolo cambiado para siempre". [139] [nb 22] En 2005, Rolling Stone calificó al LP de doble platino como el "debut trascendental" de Hendrix y lo clasificaron como el decimoquinto álbum más grande de todos los tiempos, destacando su "explotación del aullido de amplificador" y caracterizando su forma de tocar como "incendiario ... histórico en sí mismo". [141]

Festival de pop de Monterrey

Aunque era popular en Europa en ese momento, el primer sencillo estadounidense de The Experience, "Hey Joe", no alcanzó la lista Billboard Hot 100 tras su lanzamiento el 1 de mayo de 1967. [143] Su suerte mejoró cuando McCartney los recomendó a los organizadores de el Festival Pop de Monterey . Insistió en que el evento estaría incompleto sin Hendrix, a quien llamó "un as absoluto en la guitarra". McCartney acordó unirse a la junta de organizadores con la condición de que la Experiencia actúe en el festival a mediados de junio. [144]

El 18 de junio de 1967, [145] presentado por Brian Jones como "el intérprete más emocionante [que había] escuchado", Hendrix abrió con un arreglo rápido de la canción "Killing Floor" de Howlin 'Wolf, vistiendo lo que el autor Keith Shadwick describió como "ropa tan exótica como cualquiera que se exhiba en otros lugares". [146] Shadwick escribió: "[Hendrix] no solo era algo completamente nuevo musicalmente, sino una visión completamente original de cómo debería y podría verse un artista afroamericano". [147] La experiencia pasó a realizar versiones de "Hey Joe", BB King de "Rock Me Baby", Chip Taylor 's " cosa salvaje ", y Bob Dylan ' s "Like a Rolling Stone ", y cuatro composiciones originales:"Foxy Lady "," Can You See Me "," The Wind Cries Mary "y" Purple Haze ". [136] El set terminó con Hendrix destruyendo su guitarra y lanzando pedazos a la audiencia. [148] Rolling Stone 's Alex Vadukul escribió:

Cuando Jimi Hendrix prendió fuego a su guitarra en el Festival Pop de Monterey de 1967, creó uno de los momentos más perfectos del rock. De pie en la primera fila de ese concierto estaba un chico de 17 años llamado Ed Caraeff. Caraeff nunca había visto a Hendrix ni escuchado su música, pero tenía una cámara con él y le quedaba una toma en su rollo de película. Mientras Hendrix encendía su guitarra, Caraeff tomó una foto final. Se convertiría en una de las imágenes más famosas del rock and roll. [149] [nb 23]

Caraeff se paró en una silla junto al borde del escenario y tomó cuatro fotografías monocromas de Hendrix quemando su guitarra. [152] [nb 24] Caraeff estaba lo suficientemente cerca del fuego que tuvo que usar su cámara para protegerse la cara del calor. Posteriormente, Rolling Stone coloreó la imagen, combinándola con otras fotografías tomadas en el festival antes de usar la toma para la portada de una revista de 1987. [152] Según la autora Gail Buckland, el cuadro final de "Hendrix arrodillado frente a su guitarra en llamas, con las manos levantadas, es una de las imágenes más famosas del rock". [152]El autor e historiador Matthew C. Whitaker escribió que "la quema de su guitarra por parte de Hendrix se convirtió en una imagen icónica en la historia del rock y le atrajo la atención nacional". [153] El diario Los Angeles Times afirmó que, a la salida de la etapa, Hendrix "se graduó de la rumor de la leyenda". [154] El autor John McDermott escribió que "Hendrix dejó a la audiencia de Monterey atónita e incrédula por lo que acababan de escuchar y ver". [155] Según Hendrix: "Decidí destruir mi guitarra al final de una canción como sacrificio. Sacrificas las cosas que amas. Amo mi guitarra". [156] La actuación fue filmada por D. A. Pennebaker ,e incluido en el concierto documental Monterey Pop, que ayudó a Hendrix a ganar popularidad entre el público estadounidense. [157]

Después del festival, la Experiencia se reservó para cinco conciertos en Fillmore de Bill Graham , con Big Brother and the Holding Company y Jefferson Airplane . The Experience superó a Jefferson Airplane durante las dos primeras noches y los reemplazó en la parte superior de la factura en la quinta. [158] Tras su exitosa presentación en la Costa Oeste, que incluyó un concierto gratuito al aire libre en el Golden Gate Park y un concierto en el Whiskey a Go Go , The Experience fue reservado como el acto de apertura de la primera gira estadounidense de los Monkees . [159]Los Monkees solicitaron a Hendrix como acto secundario porque eran fanáticos, pero a su público joven no le gustó The Experience, que abandonó la gira después de seis shows. [160] Chandler dijo más tarde que diseñó la gira para ganar publicidad para Hendrix. [161]

Eje: Audaz como el amor

| "Audaz como el amor" Un extracto del solo de guitarra outro. La muestra demuestra la primera grabación de fase estéreo . |

¿Problemas al reproducir este archivo? Consulte la ayuda de medios . | |

El segundo álbum de Experience, Axis: Bold as Love , se abre con la pista "EXP", que utiliza retroalimentación microfónica y armónica de una manera nueva y creativa. [162] También mostró un efecto panorámico estéreo experimental en el que los sonidos que emanan de la guitarra de Hendrix se mueven a través de la imagen estéreo, girando alrededor del oyente. [163] La pieza refleja su creciente interés por la ciencia ficción y el espacio exterior . [164] Compuso la canción principal y el final del álbum en torno a dos versos y dos coros, durante los cuales combina emociones con personajes , comparándolos con los colores. [165] La coda de la canciónpresenta la primera grabación de fase estéreo . [166] [nb 25] Shadwick describió la composición como "posiblemente la pieza más ambiciosa de Axis , las extravagantes metáforas de la letra sugieren una creciente confianza" en la composición de Hendrix. [168] Su interpretación de la guitarra a lo largo de la canción está marcada por arpegios de acordes y movimiento contrapuntístico , con acordes parciales escogidos en trémolo que proporcionan la base musical para el coro, que culmina en lo que el musicólogo Andy Aledort describió como "simplemente uno de los mejores solos de guitarra eléctrica". alguna vez jugado ". [169] La pista se desvanece en el trémolo elegido32 notas dobles paradas . [170]

La fecha de lanzamiento programada para Axis casi se retrasó cuando Hendrix perdió la cinta maestra de la cara uno del LP, dejándola en el asiento trasero de un taxi londinense. [171] Con la fecha límite acercándose, Hendrix, Chandler y el ingeniero Eddie Kramer remezclaron la mayor parte del lado uno en una sola sesión nocturna, pero no pudieron igualar la calidad de la mezcla perdida de " If 6 Was 9 ". Redding tenía una grabación en cinta de esta mezcla, que tuvo que alisarse con una plancha ya que se había arrugado. [172] Durante los versos, Hendrix duplicó su canto con una línea de guitarra que tocó una octava más baja que su voz. [173]Hendrix expresó su decepción por haber vuelto a mezclar el álbum tan rápido, y sintió que podría haber sido mejor si hubieran tenido más tiempo. [171]

Axis contó con una portada psicodélica que representa a Hendrix y la Experiencia como varios avatares de Vishnu , incorporando una pintura de ellos por Roger Law , de un retrato fotográfico de Karl Ferris . [174] La pintura se superpuso luego a una copia de un cartel religioso producido en masa. [175] Hendrix declaró que la portada, que Track gastó $ 5,000 en producir, habría sido más apropiada si hubiera destacado su herencia indígena americana. [176] Dijo: "Te equivocaste ... No soy ese tipo de indio". [176] Track lanzó el álbum en el Reino Unido el 1 de diciembre de 1967, donde alcanzó el puesto número cinco, pasando 16 semanas en las listas.[177] En febrero de 1968, Axis: Bold as Love alcanzó el número tres en los Estados Unidos. [178]

Mientras que el autor y periodista Richie Unterberger describió a Axis como el álbum de Experience menos impresionante, según el autor Peter Doggett, el lanzamiento "anunció una nueva sutileza en el trabajo de Hendrix". [179] Mitchell dijo: " Axis fue la primera vez que se hizo evidente que Jimi era bastante bueno trabajando detrás de la mesa de mezclas, además de tocar, y tenía algunas ideas positivas de cómo quería que se grabaran las cosas. Podría haber sido el comienzo de cualquier conflicto potencial entre él y Chas en el estudio ". [180]

Ladyland eléctrica

Recording for the Experience's third and final studio album, Electric Ladyland, began as early as December 20, 1967, at Olympic Studios.[181] Several songs were attempted; however, in April 1968, the Experience, with Chandler as producer and engineers Eddie Kramer and Gary Kellgren, moved the sessions to the newly opened Record Plant Studios in New York.[182] As the sessions progressed, Chandler became increasingly frustrated with Hendrix's perfectionism and his demands for repeated takes.[183] Hendrix also allowed numerous friends and guests to join them in the studio, which contributed to a chaotic and crowded environment in the control room and led Chandler to sever his professional relationship with Hendrix.[183] Redding later recalled: "There were tons of people in the studio; you couldn't move. It was a party, not a session."[184] Redding, who had formed his own band in mid-1968, Fat Mattress, found it increasingly difficult to fulfill his commitments with the Experience, so Hendrix played many of the bass parts on Electric Ladyland.[183] The album's cover stated that it was "produced and directed by Jimi Hendrix".[183][nb 26]

During the Electric Ladyland recording sessions, Hendrix began experimenting with other combinations of musicians, including Jefferson Airplane's Jack Casady and Traffic's Steve Winwood, who played bass and organ, respectively, on the 15-minute slow-blues jam, "Voodoo Chile".[183] During the album's production, Hendrix appeared at an impromptu jam with B.B. King, Al Kooper, and Elvin Bishop.[186][nb 27] Electric Ladyland was released on October 25, and by mid-November it had reached number one in the US, spending two weeks at the top spot.[188] The double LP was Hendrix's most commercially successful release and his only number one album.[189] It peaked at number six in the UK, spending 12 weeks on the chart.[125] Electric Ladyland included Hendrix's cover of a Bob Dylan song, "All Along the Watchtower", which became Hendrix's highest-selling single and his only US top 40 hit, peaking at number 20; the single reached number five in the UK.[190] "Burning of the Midnight Lamp", his first recorded song to feature a wah-wah pedal, was added to the album.[191] It was originally released as his fourth single in the UK in August 1967[192] and reached number 18 on the charts.[193]

In 1989, Noe Goldwasser, the founding editor of Guitar World, described Electric Ladyland as "Hendrix's masterpiece".[194] According to author Michael Heatley, "most critics agree" that the album is "the fullest realization of Jimi's far-reaching ambitions."[183] In 2004, author Peter Doggett wrote: "For pure experimental genius, melodic flair, conceptual vision and instrumental brilliance, Electric Ladyland remains a prime contender for the status of rock's greatest album."[195] Doggett described the LP as "a display of musical virtuosity never surpassed by any rock musician."[195]

Break-up of the Experience

In January 1969, after an absence of more than six months, Hendrix briefly moved back into his girlfriend Kathy Etchingham's Brook Street apartment, which was next door to what is now the Handel House Museum in the West End of London.[196][nb 28] After a performance of "Voodoo Child", on BBC's Happening for Lulu show in January 1969, the band stopped midway through an attempt at their first hit "Hey Joe" and then launched into an instrumental version of "Sunshine of Your Love", as a tribute to the recently disbanded band Cream, until producers brought the song to a premature end.[198] Because the unplanned performance precluded Lulu's usual closing number, Hendrix was told he would never work at the BBC again.[199] During this time, the Experience toured Scandinavia, Germany, and gave their final two performances in France.[200] On February 18 and 24, they played sold-out concerts at London's Royal Albert Hall, which were the last European appearances of this lineup.[201][nb 29]

By February 1969, Redding had grown weary of Hendrix's unpredictable work ethic and his creative control over the Experience's music.[202] During the previous month's European tour, interpersonal relations within the group had deteriorated, particularly between Hendrix and Redding.[203] In his diary, Redding documented the building frustration during early 1969 recording sessions: "On the first day, as I nearly expected, there was nothing doing ... On the second it was no show at all. I went to the pub for three hours, came back, and it was still ages before Jimi ambled in. Then we argued ... On the last day, I just watched it happen for a while, and then went back to my flat."[203] The last Experience sessions that included Redding—a re-recording of "Stone Free" for use as a possible single release—took place on April 14 at Olmstead and the Record Plant in New York.[204] Hendrix then flew bassist Billy Cox to New York; they started recording and rehearsing together on April 21.[205]

The last performance of the original Experience lineup took place on June 29, 1969, at Barry Fey's Denver Pop Festival, a three-day event held at Denver's Mile High Stadium that was marked by police using tear gas to control the audience.[206] The band narrowly escaped from the venue in the back of a rental truck, which was partly crushed by fans who had climbed on top of the vehicle.[207] Before the show, a journalist angered Redding by asking why he was there; the reporter then informed him that two weeks earlier Hendrix announced that he had been replaced with Billy Cox.[208] The next day, Redding quit the Experience and returned to London.[206] He announced that he had left the band and intended to pursue a solo career, blaming Hendrix's plans to expand the group without allowing for his input as a primary reason for leaving.[209] Redding later said: "Mitch and I hung out a lot together, but we're English. If we'd go out, Jimi would stay in his room. But any bad feelings came from us being three guys who were traveling too hard, getting too tired, and taking too many drugs ... I liked Hendrix. I don't like Mitchell."[210]

Soon after Redding's departure, Hendrix began lodging at the eight-bedroom Ashokan House, in the hamlet of Boiceville near Woodstock in upstate New York, where he had spent some time vacationing in mid-1969.[211] Manager Michael Jeffery arranged the accommodations in the hope that the respite might encourage Hendrix to write material for a new album. During this time, Mitchell was unavailable for commitments made by Jeffery, which included Hendrix's first appearance on US TV—on The Dick Cavett Show—where he was backed by the studio orchestra, and an appearance on The Tonight Show where he appeared with Cox and session drummer Ed Shaughnessy.[208]

Woodstock

By 1969, Hendrix was the world's highest-paid rock musician.[2] In August, he headlined the Woodstock Music and Art Fair that included many of the most popular bands of the time.[213] For the concert, he added rhythm guitarist Larry Lee and conga players Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez. The band rehearsed for less than two weeks before the performance, and according to Mitchell, they never connected musically.[214] Before arriving at the engagement, Hendrix heard reports that the size of the audience had grown enormously, which concerned him as he did not enjoy performing for large crowds.[215] He was an important draw for the event, and although he accepted substantially less money for the appearance than his usual fee, he was the festival's highest-paid performer.[216][nb 30]

Hendrix decided to move his midnight Sunday slot to Monday morning, closing the show. The band took the stage around 8:00 a.m,[218] by which time Hendrix had been awake for more than three days.[219] The audience, which peaked at an estimated 400,000 people, was reduced to 30,000–40,000, many of whom had waited to catch a glimpse of Hendrix before leaving during his performance.[215] The festival MC, Chip Monck, introduced the group as "the Jimi Hendrix Experience", but Hendrix clarified: "We decided to change the whole thing around and call it 'Gypsy Sun and Rainbows'. For short, it's nothin' but a 'Band of Gypsys'."[220]

| "The Star-Spangled Banner" An excerpt from the beginning of "The Star-Spangled Banner", at Woodstock, August 18, 1969. The sample demonstrates Hendrix's use of feedback. |

Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Hendrix's performance included a rendition of the US national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner", with copious feedback, distortion, and sustain to imitate the sounds made by rockets and bombs.[221] Contemporary political pundits described his interpretation as a statement against the Vietnam War. Three weeks later Hendrix said: "We're all Americans ... it was like 'Go America!'... We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see."[222] Immortalized in the 1970 documentary film, Woodstock, his guitar-driven version would become part of the sixties Zeitgeist.[223] Pop critic Al Aronowitz of the New York Post wrote: "It was the most electrifying moment of Woodstock, and it was probably the single greatest moment of the sixties."[222] Images of the performance showing Hendrix wearing a blue-beaded white leather jacket with fringe, a red head-scarf, and blue jeans are regarded as iconic pictures that capture a defining moment of the era.[224][nb 31] He played "Hey Joe" during the encore, concluding the 31⁄2-day festival. Upon leaving the stage, he collapsed from exhaustion.[223][nb 32] In 2011, the editors of Guitar World named his performance of "The Star-Spangled Banner" the greatest performance of all time.[227]

Band of Gypsys

A legal dispute arose in 1966 regarding a record contract that Hendrix had entered into the previous year with producer Ed Chalpin.[228] After two years of litigation, the parties agreed to a resolution that granted Chalpin the distribution rights to an album of original Hendrix material. Hendrix decided that they would record the LP, Band of Gypsys, during two live appearances.[229] In preparation for the shows he formed an all-black power trio with Cox and drummer Buddy Miles, formerly with Wilson Pickett, the Electric Flag, and the Buddy Miles Express.[230] Critic John Rockwell described Hendrix and Miles as jazz-rock fusionists, and their collaboration as pioneering.[231] Others identified a funk and soul influence in their music.[232] Concert promoter Bill Graham called the shows "the most brilliant, emotional display of virtuoso electric guitar" that he had ever heard.[233] Biographers have speculated that Hendrix formed the band in an effort to appease members of the Black Power movement and others in the black communities who called for him to use his fame to speak up for civil rights.[234]

| "Machine Gun" An excerpt from the first guitar solo that demonstrates Hendrix's innovative use of high gain and overdrive to achieve an aggressive, sustained tone. |

Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Hendrix had been recording with Cox since April and jamming with Miles since September, and the trio wrote and rehearsed material which they performed at a series of four shows over two nights on December 31 and January 1, at the Fillmore East. They used recordings of these concerts to assemble the LP, which was produced by Hendrix.[235] The album includes the track "Machine Gun", which musicologist Andy Aledort described as the pinnacle of Hendrix's career, and "the premiere example of [his] unparalleled genius as a rock guitarist ... In this performance, Jimi transcended the medium of rock music, and set an entirely new standard for the potential of electric guitar."[236] During the song's extended instrumental breaks, Hendrix created sounds with his guitar that sonically represented warfare, including rockets, bombs, and diving planes.[237]

The Band of Gypsys album was the only official live Hendrix LP made commercially available during his lifetime; several tracks from the Woodstock and Monterey shows were released later that year.[238] The album was released in April 1970 by Capitol Records; it reached the top ten in both the US and the UK.[233] That same month a single was issued with "Stepping Stone" as the A-side and "Izabella" as the B-side, but Hendrix was dissatisfied with the quality of the mastering and he demanded that it be withdrawn and re-mixed, preventing the songs from charting and resulting in Hendrix's least successful single; it was also his last.[239]

On January 28, 1970, a third and final Band of Gypsys appearance took place; they performed during a music festival at Madison Square Garden benefiting the anti-Vietnam War Moratorium Committee titled the "Winter Festival for Peace".[240] American blues guitarist Johnny Winter was backstage before the concert; he recalled: "[Hendrix] came in with his head down, sat on the couch alone, and put his head in his hands ... He didn't move until it was time for the show."[241] Minutes after taking the stage he snapped a vulgar response at a woman who had shouted a request for "Foxy Lady". He then began playing "Earth Blues" before telling the audience: "That's what happens when earth fucks with space".[241] Moments later, he briefly sat down on the drum riser before leaving the stage.[242] Both Miles and Redding later stated that Jeffery had given Hendrix LSD before the performance.[243] Miles believed that Jeffery gave Hendrix the drugs in an effort to sabotage the current band and bring about the return of the original Experience lineup.[242] Jeffery fired Miles after the show and Cox quit, ending the Band of Gypsys.[244]

Cry of Love Tour

Soon after the abruptly ended Band of Gypsys performance and their subsequent dissolution, Jeffery made arrangements to reunite the original Experience lineup.[245] Although Hendrix, Mitchell, and Redding were interviewed by Rolling Stone in February 1970 as a united group, Hendrix never intended to work with Redding.[246] When Redding returned to New York in anticipation of rehearsals with a re-formed Experience, he was told that he had been replaced with Cox.[247] During an interview with Rolling Stone's Keith Altham, Hendrix defended the decision: "It's nothing personal against Noel, but we finished what we were doing with the Experience and Billy's style of playing suits the new group better."[245] Although an official name was never adopted for the lineup of Hendrix, Mitchell, and Cox, promoters often billed them as the Jimi Hendrix Experience or just Jimi Hendrix.[248]

During the first half of 1970, Hendrix sporadically worked on material for what would have been his next LP.[239] Many of the tracks were posthumously released in 1971 as The Cry of Love.[249] He had started writing songs for the album in 1968, but in April 1970 he told Keith Altham that the project had been abandoned.[239] Soon afterward, he and his band took a break from recording and began the Cry of Love tour at the L.A. Forum, performing for 20,000 people.[250] Set-lists during the tour included numerous Experience tracks as well as a selection of newer material.[250] Several shows were recorded, and they produced some of Hendrix's most memorable live performances. At one of them, the second Atlanta International Pop Festival, on July 4, he played to the largest American audience of his career.[251] According to authors Scott Schinder and Andy Schwartz, as many as 500,000 people attended the concert.[251] On July 17, they appeared at the New York Pop Festival; Hendrix had again consumed too many drugs before the show, and the set was considered a disaster.[252] The American leg of the tour, which included 32 performances, ended in Honolulu, Hawaii, on August 1, 1970.[253] This would be Hendrix's final concert appearance in the US.[254]

Electric Lady Studios

In 1968, Hendrix and Jeffery jointly invested in the purchase of the Generation Club in Greenwich Village.[197] They had initially planned to reopen the establishment, but when an audit of Hendrix's expenses revealed that he had incurred exorbitant fees by block-booking recording studios for lengthy sessions at peak rates they decided to convert the building [255] into a studio of his own. Hendrix could then work as much as he wanted while also reducing his recording expenditures, which had reached a reported $300,000 annually.[256] Architect and acoustician John Storyk designed Electric Lady Studios for Hendrix, who requested that they avoid right angles where possible. With round windows, an ambient lighting machine, and a psychedelic mural, Storyk wanted the studio to have a relaxing environment that would encourage Hendrix's creativity.[256] The project took twice as long as planned and cost twice as much as Hendrix and Jeffery had budgeted, with their total investment estimated at $1 million.[257][nb 33]

Hendrix first used Electric Lady on June 15, 1970, when he jammed with Steve Winwood and Chris Wood of Traffic; the next day, he recorded his first track there, "Night Bird Flying".[258] The studio officially opened for business on August 25, and a grand opening party was held the following day.[258] Immediately afterwards, Hendrix left for England; he never returned to the States.[259] He boarded an Air India flight for London with Cox, joining Mitchell for a performance as the headlining act of the Isle of Wight Festival.[260]

European tour

When the European leg of the Cry of Love tour began, Hendrix was longing for his new studio and creative outlet, and was not eager to fulfill the commitment. On September 2, 1970, he abandoned a performance in Aarhus after three songs, stating: "I've been dead a long time".[261] Four days later, he gave his final concert appearance, at the Isle of Fehmarn Festival in Germany.[262] He was met with booing and jeering from fans in response to his cancellation of a show slated for the end of the previous night's bill due to torrential rain and risk of electrocution.[263][nb 34] Immediately following the festival, Hendrix, Mitchell, and Cox traveled to London.[265]

Three days after the performance, Cox, who was suffering from severe paranoia after either taking LSD or being given it unknowingly, quit the tour and went to stay with his parents in Pennsylvania.[266] Within days of Hendrix's arrival in England, he had spoken with Chas Chandler, Alan Douglas, and others about leaving his manager, Michael Jeffery.[267] On September 16, Hendrix performed in public for the last time during an informal jam at Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club in Soho with Eric Burdon and his latest band, War.[268] They began by playing a few of their recent hits, and after a brief intermission Hendrix joined them during "Mother Earth" and "Tobacco Road". His performance was uncharacteristically subdued; he quietly played backing guitar, and refrained from the histrionics that people had come to expect from him.[269] He died less than 48 hours later.[270]

Drugs and alcohol

Hendrix entered a small club in Clarksville, Tennessee, in July 1962, drawn in by live music. He stopped for a drink and ended up spending most of the $400 that he had saved during his time in the Army. "I went in this jazz joint and had a drink," he explained. "I liked it and I stayed. People tell me I get foolish, good-natured sometimes. Anyway, I guess I felt real benevolent that day. I must have been handing out bills to anyone that asked me. I came out of that place with sixteen dollars left."[271] Alcohol eventually became "the scourge of his existence, driving him to fits of pique, even rare bursts of atypical, physical violence".[272]

— Kathy Etchingham[273]

Roby and Schreiber assert that Hendrix first used LSD when he met Linda Keith in late 1966. Shapiro and Glebbeek, however, assert that Hendrix used it in June 1967 at the earliest while attending the Monterey Pop Festival.[274] According to Hendrix biographer Charles Cross, the subject of drugs came up one evening in 1966 at Keith's New York apartment. One of Keith's friends offered Hendrix acid, a street name for LSD, but Hendrix asked for LSD instead, showing what Cross describes as "his naivete and his complete inexperience with psychedelics".[275] Before that, Hendrix had only sporadically used drugs, experimenting with cannabis, hashish, amphetamines, and occasionally cocaine.[275] After 1967, he regularly used cannabis, hashish, LSD, and amphetamines, particularly while touring.[276] According to Cross, "few stars were as closely associated with the drug culture as Jimi".[277]

Drug abuse and violence

When Hendrix drank to excess or mixed drugs with alcohol, often he became angry and violent.[278] His friend Herbie Worthington said Hendrix "simply turned into a bastard" when he drank.[279] According to friend Sharon Lawrence, liquor "set off a bottled-up anger, a destructive fury he almost never displayed otherwise".[280]

In January 1968, the Experience travelled to Sweden to start a one-week tour of Europe. During the early morning hours of the first day, Hendrix got into a drunken brawl in the Hotel Opalen in Gothenburg, smashing a plate-glass window and injuring his right hand, for which he received medical treatment.[279] The incident culminated in his arrest and release, pending a court appearance that resulted in a large fine.[281]

In 1969, Hendrix rented a house in Benedict Canyon, California, that was burglarized. Later, while under the influence of drugs and alcohol, he accused his friend Paul Caruso of the theft, threw punches and stones at him, and chased him away from his house.[282] A few days later Hendrix hit his girlfriend, Carmen Borrero, above her eye with a vodka bottle during a drunken, jealous rage, and gave her a cut that necessitated stitches.[279]

Canadian drug charges and trial

Hendrix was passing through customs at Toronto International Airport on May 3, 1969, when authorities found a small amount of heroin and hashish in his luggage.[283] Four hours later, he was formally charged with drug possession and released on $10,000 bail. He was required to return on May 5 for an arraignment hearing.[284] The incident proved stressful for Hendrix, and it weighed heavily on his mind during the seven months that he awaited trial, which took place in December 1969.[283] For the Crown to prove possession, they had to show that Hendrix knew that the drugs were there.[285] During the jury trial, he testified that a fan had given him a vial of what he thought was legal medication which he put in his bag.[286] He was acquitted of the charges.[287] Mitchell and Redding later revealed that everyone had been warned about a planned drug bust the day before flying to Toronto; both men also stated that they believed that the drugs had been planted in Hendrix's bag without his knowledge.[288]

Death, post-mortem, and burial

Details are disputed concerning Hendrix's last day and death. He spent much of September 17, 1970, with Monika Dannemann in London, the only witness to his final hours.[289][290] Dannemann said that she prepared a meal for them at her apartment in the Samarkand Hotel around 11 p.m., when they shared a bottle of wine.[291] She drove him to the residence of an acquaintance at approximately 1:45 a.m., where he remained for about an hour before she picked him up and drove them back to her flat at 3 a.m.[292] She said that they talked until around 7 a.m., when they went to sleep. Dannemann awoke around 11 a.m. and found Hendrix breathing but unconscious and unresponsive. She called for an ambulance at 11:18 a.m., and it arrived nine minutes later.[293] Paramedics transported Hendrix to St Mary Abbot's Hospital where Dr. John Bannister pronounced him dead at 12:45 p.m. on September 18.[294][295][296]

Coroner Gavin Thurston ordered a post-mortem examination which was performed on September 21 by Professor Robert Donald Teare, a forensic pathologist.[297] Thurston completed the inquest on September 28 and concluded that Hendrix aspirated his own vomit and died of asphyxia while intoxicated with barbiturates.[298] Citing "insufficient evidence of the circumstances", he declared an open verdict.[299] Dannemann later revealed that Hendrix had taken nine of her prescribed Vesparax sleeping tablets, 18 times the recommended dosage.[300]

Desmond Henley embalmed Hendrix's body[301] which was flown to Seattle on September 29.[302] Hendrix's family and friends held a service at Dunlap Baptist Church in Seattle's Rainier Valley on Thursday, October 1; his body was interred at Greenwood Cemetery in nearby Renton,[303] the location of his mother's grave.[304] Family and friends traveled in 24 limousines, and more than 200 people attended the funeral, including Mitch Mitchell, Noel Redding, Miles Davis, John Hammond, and Johnny Winter.[305][306]

Jimi Hendrix is often cited as one example of an allegedly disproportionate number of musicians dying at age 27, a phenomenon referred to as the 27 Club.

Unauthorized and posthumous releases

By 1967, as Hendrix was gaining in popularity, many of his pre-Experience recordings were marketed to an unsuspecting public as Jimi Hendrix albums, sometimes with misleading later images of Hendrix.[307] The recordings, which came under the control of producer Ed Chalpin of PPX, with whom Hendrix had signed a recording contract in 1965, were often re-mixed between their repeated reissues, and licensed to record companies such as Decca and Capitol.[308][309] Hendrix publicly denounced the releases, describing them as "malicious" and "greatly inferior", stating: "At PPX, we spent on average about one hour recording a song. Today I spend at least twelve hours on each song."[310] These unauthorized releases have long constituted a substantial part of his recording catalogue, amounting to hundreds of albums.[311]

Some of Hendrix's unfinished fourth studio album was released as the 1971 title The Cry of Love.[249] Although the album reached number three in the US and number two in the UK, producers Mitchell and Kramer later complained that they were unable to make use of all the available songs because some tracks were used for 1971's Rainbow Bridge; still others were issued on 1972's War Heroes.[312] Material from The Cry of Love was re-released in 1997 as First Rays of the New Rising Sun, along with the other tracks that Mitchell and Kramer had wanted to include.[313][nb 35] Four years after Hendrix's death, producer Alan Douglas acquired the rights to produce unreleased music by Hendrix; he attracted criticism for using studio musicians to replace or add tracks.[315]

In 1993, MCA Records delayed a multimillion-dollar sale of Hendrix's publishing copyrights because Al Hendrix was unhappy about the arrangement.[316] He acknowledged that he had sold distribution rights to a foreign corporation in 1974, but stated that it did not include copyrights and argued that he had retained veto power of the sale of the catalogue.[316] Under a settlement reached in July 1995, Al Hendrix regained control of his son's song and image rights.[317] He subsequently licensed the recordings to MCA through the family-run company Experience Hendrix LLC, formed in 1995.[318] In August 2009, Experience Hendrix announced that it had entered a new licensing agreement with Sony Music Entertainment's Legacy Recordings division, to take effect in 2010.[319] Legacy and Experience Hendrix launched the 2010 Jimi Hendrix Catalog Project starting with the release of Valleys of Neptune in March of that year.[320] In the months before his death, Hendrix recorded demos for a concept album tentatively titled Black Gold, now in the possession of Experience Hendrix LLC, but it has not been released.[321][nb 36]

Equipment

Guitars

Hendrix played a variety of guitars, but was most associated with the Fender Stratocaster.[323] He acquired his first in 1966, when a girlfriend loaned him enough money to purchase a used Stratocaster built around 1964.[324] He used it often during performances and recordings.[325] In 1967, he described the Stratocaster as "the best all-around guitar for the stuff we're doing"; he praised its "bright treble and deep bass".[326]

Hendrix mainly played right-handed guitars that were turned upside down and restrung for left-hand playing.[327] Because of the slant of the Stratocaster's bridge pickup, his lowest string had a brighter sound, while his highest string had a darker sound, the opposite of the intended design.[328] Hendrix also used Fender Jazzmasters, Duosonics, two different Gibson Flying Vs, a Gibson Les Paul, three Gibson SGs, a Gretsch Corvette, and a Fender Jaguar.[329] He used a white Gibson SG Custom for his performances on The Dick Cavett Show in September 1969, and a black Gibson Flying V during the Isle of Wight festival in 1970.[330][nb 37]

Amplifiers

During 1965, and 1966, while Hendrix was playing back-up for soul and R&B acts in the US, he used an 85-watt Fender Twin Reverb amplifier.[332] When Chandler brought Hendrix to England in October 1966, he supplied him with 30-watt Burns amps, which Hendrix thought were too small for his needs.[333][nb 38] After an early London gig when he was unable to use his Fender Twin, he asked about the Marshall amps he had noticed other groups using.[333] Years earlier, Mitch Mitchell had taken drum lessons from Marshall founder Jim Marshall, and he introduced Hendrix to Marshall.[334] At their initial meeting, Hendrix bought four speaker cabinets and three 100-watt Super Lead amplifiers; he grew accustomed to using all three in unison.[333] The equipment arrived on October 11, 1966, and the Experience used it during their first tour.[333]

Marshall amps were important to the development of Hendrix's overdriven sound and his use of feedback, creating what author Paul Trynka described as a "definitive vocabulary for rock guitar".[335] Hendrix usually turned all the control knobs to the maximum level, which became known as the Hendrix setting.[336] During the four years prior to his death, he purchased between 50 and 100 Marshall amplifiers.[337] Jim Marshall said Hendrix was "the greatest ambassador" his company ever had.[338]

Effects

One of Hendrix's signature effects was the wah-wah pedal, which he first heard used with an electric guitar in Cream's "Tales of Brave Ulysses", released in May 1967.[340] That July, while performing at the Scene club in New York City, Hendrix met Frank Zappa, whose band the Mothers of Invention were performing at the adjacent Garrick Theater. Hendrix was fascinated by Zappa's application of the pedal, and he experimented with one later that evening.[341][nb 39] He used a wah pedal during the opening to "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)", creating one of the best-known wah-wah riffs of the classic rock era.[343] He also uses the effect on "Up from the Skies", "Little Miss Lover", and "Still Raining, Still Dreaming".[342]

Hendrix used a Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face and a Vox wah pedal during recording sessions and performances, but also experimented with other guitar effects.[344] He enjoyed a fruitful long-term collaboration with electronics enthusiast Roger Mayer, whom he once called "the secret" of his sound.[345] Mayer introduced him to the Octavia, an octave-doubling effect pedal, in December 1966, and he first recorded with it during the guitar solo to "Purple Haze".[346]

Hendrix also used the Uni-Vibe, designed to simulate the modulation effects of a rotating Leslie speaker. He uses the effect during his performance at Woodstock and on the Band of Gypsys track "Machine Gun", which prominently features the Uni-vibe along with an Octavia and a Fuzz Face.[347] For performances, he plugged his guitar into the wah-wah, which was connected to the Fuzz Face, then the Uni-Vibe, and finally a Marshall amplifier.[348]

Influences

As an adolescent in the 1950s, Hendrix became interested in rock and roll artists such as Elvis Presley, Little Richard, and Chuck Berry.[349] In 1968, he told Guitar Player magazine that electric blues artists Muddy Waters, Elmore James, and B.B. King inspired him during the beginning of his career; he also cited Eddie Cochran as an early influence.[350] Of Muddy Waters, the first electric guitarist of which Hendrix became aware, he said: "I heard one of his records when I was a little boy and it scared me to death because I heard all of these sounds."[351] In 1970, he told Rolling Stone that he was a fan of western swing artist Bob Wills and while he lived in Nashville, the television show the Grand Ole Opry.[352]

— Hendrix on jazz music[353]

Cox stated that during their time serving in the US military, he and Hendrix primarily listened to southern blues artists such as Jimmy Reed and Albert King. According to Cox, "King was a very, very powerful influence".[350] Howlin' Wolf also inspired Hendrix, who performed Wolf's "Killing Floor" as the opening song of his US debut at the Monterey Pop Festival.[354] The influence of soul artist Curtis Mayfield can be heard in Hendrix's guitar playing, and the influence of Bob Dylan can be heard in Hendrix's songwriting; he was known to play Dylan's records repeatedly, particularly Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde.[355]

Legacy

— Guitar Player magazine, May 2012[356]

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame biography for the Experience states: "Jimi Hendrix was arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music. Hendrix expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar into areas no musician had ever ventured before. His boundless drive, technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll."[1] Musicologist Andy Aledort described Hendrix as "one of the most creative" and "influential musicians that has ever lived".[357] Music journalist Chuck Philips wrote: "In a field almost exclusively populated by white musicians, Hendrix has served as a role model for a cadre of young black rockers. His achievement was to reclaim title to a musical form pioneered by black innovators like Little Richard and Chuck Berry in the 1950s."[358]

Hendrix favored overdriven amplifiers with high volume and gain.[122] He was instrumental in developing the previously undesirable technique of guitar amplifier feedback, and helped to popularize use of the wah-wah pedal in mainstream rock.[359] He rejected the standard barre chord fretting technique used by most guitarists in favor of fretting the low 6th string root notes with his thumb.[360] He applied this technique during the beginning bars of "Little Wing", which allowed him to sustain the root note of chords while also playing melody. This method has been described as piano style, with the thumb playing what a pianist's left hand would play and the other fingers playing melody as a right hand.[361] Having spent several years fronting a trio, he developed an ability to play rhythm chords and lead lines together, giving the audio impression that more than one guitarist was performing.[362][nb 40] He was the first artist to incorporate stereophonic phasing effects in rock music recordings.[365] Holly George-Warren of Rolling Stone wrote: "Hendrix pioneered the use of the instrument as an electronic sound source. Players before him had experimented with feedback and distortion, but Hendrix turned those effects and others into a controlled, fluid vocabulary every bit as personal as the blues with which he began."[3][nb 41]

While creating his unique musical voice and guitar style, Hendrix synthesized diverse genres, including blues, R&B, soul, British rock, American folk music, 1950s rock and roll, and jazz.[367] Musicologist David Moskowitz emphasized the importance of blues music in Hendrix's playing style, and according to authors Steven Roby and Brad Schreiber, "[He] explored the outer reaches of psychedelic rock".[368] His influence is evident in a variety of popular music formats, and he has contributed significantly to the development of hard rock, heavy metal, funk, post-punk, grunge,[369] and hip hop music.[370] His lasting influence on modern guitar players is difficult to overstate; his techniques and delivery have been abundantly imitated by others.[371] Despite his hectic touring schedule and notorious perfectionism, he was a prolific recording artist who left behind numerous unreleased recordings.[372] More than 40 years after his death, Hendrix remains as popular as ever, with annual album sales exceeding that of any year during his lifetime.[373]

Hendrix has influenced numerous funk and funk rock artists, including Prince, George Clinton, John Frusciante, of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Eddie Hazel of Funkadelic, and Ernie Isley of the Isley Brothers.[374] Grunge guitarists such as Jerry Cantrell of Alice in Chains,[375] and Mike McCready and Stone Gossard of Pearl Jam have cited Hendrix as an influence.[369] Hendrix's influence also extends to many hip hop artists, including De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Digital Underground, Beastie Boys, and Run–D.M.C.[376] Miles Davis was deeply impressed by Hendrix, and he compared Hendrix's improvisational abilities with those of saxophonist John Coltrane.[377][nb 42] Hendrix also influenced Black Sabbath,[379] industrial artist Marilyn Manson,[380] blues legend Stevie Ray Vaughan, Randy Hansen,[381] Uli Jon Roth,[382] pop singer Halsey,[383] Kiss's Ace Frehley,[384] Metallica's Kirk Hammett, Aerosmith's Brad Whitford,[385] Judas Priest's Richie Faulkner,[386] instrumental rock guitarist Joe Satriani, King's X singer/bassist Doug Pinnick,[387] Frank Zappa/David Bowie/Talking Heads/King Crimson/Nine Inch Nails hired gun Adrian Belew,[388] and heavy metal virtuoso Yngwie Malmsteen, who said: "[Hendrix] created modern electric playing, without question ... He was the first. He started it all. The rest is history."[389] "For many", Hendrix was "the preeminent black rocker", according to Jon Caramanica.[390] Members of the Soulquarians, an experimental black music collective active during the late 1990s and early 2000s, were influenced by the creative freedom in Hendrix's music and extensively used Electric Lady Studios to work on their own music.[391]

Recognition and awards

Hendrix received several prestigious rock music awards during his lifetime and posthumously. In 1967, readers of Melody Maker voted him the Pop Musician of the Year.[392] In 1968, Rolling Stone declared him the Performer of the Year.[392] Also in 1968, the City of Seattle gave him the keys to the city.[393] Disc & Music Echo newspaper honored him with the World Top Musician of 1969 and in 1970 Guitar Player magazine named him the Rock Guitarist of the Year.[394]

Rolling Stone ranked his three non-posthumous studio albums, Are You Experienced (1967), Axis: Bold as Love (1967), and Electric Ladyland (1968) among the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[395] They ranked Hendrix number one on their list of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time, and number six on their list of the 100 greatest artists of all time.[396] Guitar World's readers voted six of Hendrix's solos among the top 100 Greatest Guitar Solos of All Time: "Purple Haze" (70), "The Star-Spangled Banner" (52; from Live at Woodstock), "Machine Gun" (32; from Band of Gypsys), "Little Wing" (18), "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)" (11), and "All Along the Watchtower" (5).[397] Rolling Stone placed seven of his recordings in their list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time: "Purple Haze" (17), "All Along the Watchtower" (47) "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)" (102), "Foxy Lady" (153), "Hey Joe" (201), "Little Wing" (366), and "The Wind Cries Mary" (379).[398] They also included three of Hendrix's songs in their list of the 100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time: "Purple Haze" (2), "Voodoo Child" (12), and "Machine Gun" (49).[399]

A star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame was dedicated to Hendrix on November 14, 1991, at 6627 Hollywood Boulevard.[400] The Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992, and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005.[1][401] In 1998, Hendrix was inducted into the Native American Music Hall of Fame during its first year.[402] In 1999, readers of Rolling Stone and Guitar World ranked Hendrix among the most important musicians of the 20th century.[403] In 2005, his debut album, Are You Experienced, was one of 50 recordings added that year to the U.S. National Recording Registry in the Library of Congress, "[to] be preserved for all time ... [as] part of the nation's audio legacy".[404] In Seattle, November 27, 1992, which would have been Hendrix's 50th birthday, was made Jimi Hendrix Day, largely due to the efforts of his boyhood friend, guitarist Sammy Drain.[405][406]

The blue plaque identifying Hendrix's former residence at 23 Brook Street, London, (next door to the former residence of George Frideric Handel) was the first issued by English Heritage to commemorate a pop star.[407] A memorial statue of Hendrix playing a Stratocaster stands near the corner of Broadway and Pine Streets in Seattle. In May 2006, the city renamed a park near its Central District Jimi Hendrix Park, in his honor.[408] In 2012, an official historic marker was erected on the site of the July 1970 Second Atlanta International Pop Festival near Byron, Georgia. The marker text reads, in part: "Over thirty musical acts performed, including rock icon Jimi Hendrix playing to the largest American audience of his career."[409]