| Reino de FranciaRoyaume de France | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1814–1815 1815–1830 | |||||||||||

Lema: Montjoie Saint Denis! "¡Montjoy Saint Denis!" | |||||||||||

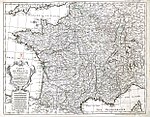

El Reino de Francia en 1818 | |||||||||||

| Capital | París | ||||||||||

| Lenguajes comunes | francés | ||||||||||

| Religión | catolicismo romano | ||||||||||

| Gobierno | Monarquía constitucional unitaria | ||||||||||

| Rey | |||||||||||

| • 1814–1824 | Luis XVIII | ||||||||||

| • 1824-1830 | Carlos X | ||||||||||

| Primer ministro | |||||||||||

| • 1815 (primero) | Charles de Bénévent | ||||||||||

| • 1829-1830 (último) | Jules de Polignac | ||||||||||

| Legislatura | Parlamento | ||||||||||

| • Cámara alta | Cámara de pares | ||||||||||

| • Cámara baja | Cámara de Diputados | ||||||||||

| Historia | |||||||||||

| • Restauración | 3 de mayo de 1814 | ||||||||||

| • Tratado de París | 30 de mayo de 1814 | ||||||||||

| • Constitución adoptada | 4 de junio de 1814 | ||||||||||

| • Cien días | 20 de marzo - 7 de julio de 1815 | ||||||||||

| • Invasión de España | 6 de abril de 1823 | ||||||||||

| • Revolución de julio | 26 de julio de 1830 | ||||||||||

| Área | |||||||||||

| 1815 | 560.000 km 2 (220.000 millas cuadradas) | ||||||||||

| Divisa | Franco francés | ||||||||||

| Código ISO 3166 | FR | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Parte de una serie sobre el |

|---|

| Historia de Francia |

|

| Cronología |

| Portal de Francia |

La Restauración borbónica fue el período de la historia francesa que siguió a la primera caída de Napoleón el 3 de mayo de 1814 hasta la Revolución de julio del 26 de julio de 1830, pero interrumpida por la Guerra de los Cien Días del 19 de marzo de 1815 al 8 de julio de 1815. Los hermanos del ejecutado Luis XVI , a saber, Luis XVIII y Carlos X , subieron sucesivamente al trono e instituyeron un gobierno conservador con el objetivo de restaurar las propiedades, si no todas las instituciones, del Antiguo Régimen . Los partidarios exiliados de la monarquía regresaron a Francia. No obstante, fueron incapaces de revertir la mayoría de los cambios realizados por la Revolución Francesa.y Napoleón. Agotada por décadas de guerra , la nación experimentó un período de paz interna y externa, prosperidad económica estable y los preliminares de la industrialización. [1]

Antecedentes [ editar ]

Después de la Revolución Francesa (1789-1799), Napoleón se convirtió en gobernante de Francia. Después de años de expansión de su Imperio francés por sucesivas victorias militares, una coalición de potencias europeas lo derrotó en la Guerra de la Sexta Coalición , acabó con el Primer Imperio en 1814 y restauró la monarquía a los hermanos de Luis XVI. La Restauración borbónica duró aproximadamente desde el 6 de abril de 1814 hasta los levantamientos populares de la Revolución de julio de 1830. Hubo un interludio en la primavera de 1815, los " Cien Días ", cuando el regreso de Napoleón obligó a los Borbones a huir de Francia. Cuando Napoleón fue nuevamente derrotado por la Séptima Coalición , regresaron al poder en julio.

En el consejo de paz del Congreso de Viena , los Borbones fueron tratados cortésmente por las monarquías victoriosas, pero tuvieron que renunciar a casi todas las conquistas territoriales logradas por la Francia revolucionaria y napoleónica desde 1789.

Monarquía constitucional [ editar ]

A diferencia del Ancien Régime absolutista , el régimen borbónico de la Restauración fue una monarquía constitucional , con algunos límites en su poder. El nuevo rey, Luis XVIII, aceptó la gran mayoría de las reformas instituidas entre 1792 y 1814. La continuidad era su política básica. No trató de recuperar tierras y propiedades arrebatadas a los exiliados realistas. Continuó de manera pacífica los principales objetivos de la política exterior de Napoleón, como la limitación de la influencia austriaca. Dio marcha atrás a Napoleón con respecto a España y el Imperio Otomano , restableciendo las amistades que habían prevalecido hasta 1792. [2]

Políticamente, el período se caracterizó por una fuerte reacción conservadora, y los consiguientes disturbios y disturbios civiles menores pero persistentes. [3] De lo contrario, la clase política se mantuvo relativamente estable hasta el reinado posterior de Charles X . [4] También vio el restablecimiento de la Iglesia Católica como un poder importante en la política francesa. [5] A lo largo de la Restauración borbónica, Francia experimentó un período de prosperidad económica estable y los preliminares de la industrialización. [1]

Cambios permanentes en la sociedad francesa [ editar ]

Las épocas de la Revolución Francesa y Napoleón trajeron una serie de cambios importantes a Francia que la Restauración Borbónica no revirtió. [6] [7] [8] Primero, Francia estaba ahora altamente centralizada, con todas las decisiones importantes tomadas en París. La geografía política fue completamente reorganizada y uniformada, dividiendo la nación en más de 80 departamentos que han perdurado hasta el siglo XXI. Cada departamento tenía una estructura administrativa idéntica y estaba estrictamente controlado por un prefecto designado por París. La maraña de jurisdicciones legales superpuestas del antiguo régimen se ha abolido, y ahora existe un código legal estandarizado, administrado por jueces designados por París y respaldado por la policía bajo control nacional.

Los gobiernos revolucionarios habían confiscado todas las tierras y edificios de la Iglesia Católica , vendiéndolos a innumerables compradores de clase media, y era políticamente imposible restaurarlos. El obispo todavía gobernaba su diócesis (que estaba alineada con los nuevos límites del departamento) y se comunicaba con el Papa a través del gobierno de París. Obispos, sacerdotes, monjas y otros religiosos recibieron salarios estatales.

Se conservaron todos los antiguos ritos y ceremonias religiosas y el gobierno mantuvo los edificios religiosos. A la Iglesia se le permitió operar sus propios seminarios y, hasta cierto punto, también escuelas locales, aunque esto se convirtió en un tema político central en el siglo XX. Los obispos eran mucho menos poderosos que antes y no tenían voz política. Sin embargo, la Iglesia Católica se reinventó a sí misma con un nuevo énfasis en la piedad personal que le dio un control sobre la psicología de los fieles. [9] La educación pública estaba centralizada, con el Gran Maestro de la Universidad de Francia controlando todos los elementos del sistema educativo nacional de París. Se abrieron nuevas universidades técnicas en París que hasta el día de hoy tienen un papel fundamental en la formación de la élite.[10]

El conservadurismo se dividió amargamente en la vieja aristocracia que regresaba y las nuevas élites que surgieron bajo Napoleón después de 1796. La vieja aristocracia estaba ansiosa por recuperar su tierra, pero no sentía lealtad hacia el nuevo régimen. La élite más reciente, la "nobleza de imperio", ridiculizó al grupo más antiguo como un remanente obsoleto de un régimen desacreditado que había llevado a la nación al desastre. Ambos grupos compartían el miedo al desorden social, pero tanto el nivel de desconfianza como las diferencias culturales eran demasiado grandes y la monarquía demasiado inconsistente en sus políticas para que la cooperación política fuera posible. [11]

La vieja aristocracia que regresó recuperó gran parte de la tierra que habían poseído directamente. Sin embargo, perdieron todos sus antiguos derechos señoriales sobre el resto de las tierras de cultivo y los campesinos ya no estaban bajo su control. La aristocracia prerrevolucionaria se había entretenido con las ideas de la Ilustración y el racionalismo. Ahora la aristocracia era mucho más conservadora y apoyaba a la Iglesia Católica. Para los mejores trabajos, la meritocracia era la nueva política, y los aristócratas tenían que competir directamente con la creciente clase empresarial y profesional.

El sentimiento público anticlerical se hizo más fuerte que nunca, pero ahora se basaba en ciertos elementos de la clase media e incluso el campesinado. Las grandes masas francesas eran campesinos en el campo o trabajadores empobrecidos en las ciudades. Obtuvieron nuevos derechos y un nuevo sentido de posibilidades. Aunque liberado de muchas de las antiguas cargas, controles e impuestos, el campesinado seguía siendo muy tradicional en su comportamiento social y económico. Muchos tomaron hipotecas con entusiasmo para comprar la mayor cantidad de tierra posible para sus hijos, por lo que la deuda fue un factor importante en sus cálculos. La clase trabajadora en las ciudades era un elemento pequeño y había sido liberada de muchas restricciones impuestas por los gremios medievales. Sin embargo, Francia tardó mucho en industrializarse y gran parte del trabajo siguió siendo pesado sin maquinaria o tecnología que lo ayudara.Francia todavía estaba dividida en localidades, especialmente en términos de idioma, pero ahora había un nacionalismo francés emergente que centraba el orgullo nacional en el ejército y los asuntos exteriores.[12]

Panorama político [ editar ]

En abril de 1814, los Ejércitos de la Sexta Coalición devolvieron al trono a Luis XVIII de Francia ; los historiógrafos lo llamaron el " pretendiente borbónico ", especialmente los desfavorables a la restauración de la monarquía. Se redactó una constitución, la Carta de 1814 . Presentaba a todos los franceses como iguales ante la ley, [13] pero conservaba una prerrogativa sustancial para el rey y la nobleza y limitaba el voto a quienes pagaban al menos 300 francos al año en impuestos directos.

Luis XVIII fue el jefe supremo del estado. Dirigió las fuerzas terrestres y marítimas, declaró la guerra, celebró tratados de paz, alianza y comercio, nombró hombres para todos los lugares de la administración pública e hizo los reglamentos y ordenanzas necesarios para la ejecución de las leyes y la seguridad del estado. [14] Luis fue más liberal que su sucesor Carlos X , eligiendo muchos gabinetes centristas. [15]

Luis XVIII murió en septiembre de 1824. Fue sucedido por su hermano Carlos. Carlos X persiguió una forma de gobierno más conservadora que Luis. Sus leyes más reaccionarias incluyeron la Ley contra el sacrilegio (1825-1830). El rey y sus ministros intentaron manipular el resultado de una elección general en 1830, a través de sus ordenanzas de julio . Las ordenanzas provocaron una revolución contra Charles; el 2 de agosto de 1830, Carlos había huido de París y abdicó en favor de su nieto Enrique, conde de Chambord . El reinado teórico de Enrique terminó el 9 de agosto cuando la Cámara de Diputados declaró regente a Luis Felipe de Orleans , que actualmente gobernaba Francia, rey de los franceses, marcando así el comienzo de laMonarquía de julio .

Luis XVIII, 1814-1824 [ editar ]

Primera restauración (1814) [ editar ]

La restauración de Luis XVIII al trono en 1814 se llevó a cabo en gran parte gracias al apoyo del ex ministro de Relaciones Exteriores de Napoleón, Talleyrand , quien convenció a las potencias aliadas victoriosas de la conveniencia de una Restauración borbónica. [16] Los aliados habían dividido inicialmente en el mejor candidato para el trono: Bretaña favoreció a los Borbones, los austriacos consideran una regencia para el hijo de Napoleón, François Bonaparte , y los rusos estaban abiertas ya sea al duque de Orléans , Louis Philippe , o Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte , ex mariscal de Napoleón , quien era presunto herederoal trono sueco. A Napoleón se le ofreció mantener el trono en febrero de 1814, con la condición de que Francia regresara a sus fronteras de 1792, pero él se negó. [16] La viabilidad de la Restauración estaba en duda, pero el atractivo de la paz para un público francés cansado de la guerra y las demostraciones de apoyo a los Borbones en París, Burdeos , Marsella y Lyon ayudaron a tranquilizar a los aliados. [17]

Louis, de acuerdo con la Declaración de Saint-Ouen , [18] otorgó una constitución escrita, la Carta de 1814 , que garantizaba una legislatura bicameral con una Cámara de Pares hereditaria / nombrada y una Cámara de Diputados elegida - su función era consultiva ( excepto en impuestos), ya que solo el Rey tenía el poder de proponer o sancionar leyes y nombrar o revocar ministros. [19] La franquicia se limitaba a los hombres con una propiedad considerable, y solo el 1% de la gente podía votar. [19] Muchas de las reformas legales, administrativas y económicas del período revolucionario quedaron intactas; laEl Código Napoleónico , [19] que garantizaba la igualdad jurídica y las libertades civiles, las biens nationaux de los campesinos y el nuevo sistema de dividir el país en departamentos no fueron deshechos por el nuevo rey. Las relaciones entre la Iglesia y el Estado quedaron reguladas por el Concordato de 1801 . Sin embargo, a pesar de que la Carta era una condición de la Restauración, el preámbulo declaraba que era una "concesión y donación", otorgada "por el libre ejercicio de nuestra autoridad real". [20]

Después de una primera oleada de popularidad sentimental, los gestos de Louis para revertir los resultados de la Revolución Francesa rápidamente le hicieron perder el apoyo entre la mayoría desfavorecida. Actos simbólicos como el reemplazo de la bandera tricolor por la bandera blanca , el título de Luis como el "XVIII" (como sucesor de Luis XVII , que nunca gobernó) y como "Rey de Francia" en lugar de "Rey de los franceses". , y el reconocimiento de la monarquía de los aniversarios de la muerte de Luis XVI y María Antonieta fueron significativos. Una fuente más tangible de antagonismo fue la presión aplicada a los poseedores de biens nationaux(las tierras confiscadas por la revolución) por la Iglesia Católica y los emigrados que regresan intentan recuperar sus antiguas tierras. [21] Otros grupos que tenían resentimientos hacia Louis incluían el ejército, los no católicos y los trabajadores afectados por una recesión de la posguerra y las importaciones británicas. [22]

Los Cien Días [ editar ]

Los emisarios de Napoleón le informaron de este creciente descontento, [22] y, el 20 de marzo de 1815, regresó a París desde Elba . En su Ruta Napoleón , la mayoría de las tropas enviadas para detener su marcha, incluidas algunas que eran nominalmente realistas, se sintieron más inclinadas a unirse al ex Emperador que a detenerlo. [23] Luis huyó de París a Gante el 19 de marzo. [24] [25]

Después de que Napoleón fuera derrotado en la batalla de Waterloo y enviado de nuevo al exilio, Luis regresó. Durante su ausencia, se sofocó una pequeña revuelta en la Vendée tradicionalmente pro-realista , pero por lo demás hubo pocos actos subversivos que favorecieran la Restauración, a pesar de que la popularidad de Napoleón comenzó a decaer. [26]

Segunda Restauración (1815) [ editar ]

Talleyrand fue nuevamente influyente al ver que los Borbones volvían al poder, al igual que Fouché , [27] [28] ministro de policía de Napoleón durante los Cien Días. Esta Segunda Restauración vio el comienzo del Segundo Terror Blanco , principalmente en el sur, cuando grupos no oficiales que apoyaban a la monarquía buscaron venganza contra aquellos que habían ayudado al regreso de Napoleón: entre 200 y 300 personas murieron, mientras que miles huyeron. Aproximadamente 70.000 funcionarios del gobierno fueron despedidos. Los perpetradores pro-Borbones a menudo se conocían como los Verdet por sus cockets verdes, que era el color del conde de Artois, siendo este el título de Carlos X en ese momento, quien estaba asociado con los ultrarrealistas de línea dura.o Ultras. Después de un período en el que las autoridades locales miraban impotentes la violencia, el rey y sus ministros enviaron funcionarios para restablecer el orden. [29]

Se firmó un nuevo Tratado de París el 20 de noviembre de 1815, que tenía términos más punitivos que el tratado de 1814 . Se ordenó a Francia que pagara 700 millones de francos en indemnizaciones, y las fronteras del país se redujeron a su estado de 1790, en lugar de 1792 como en el tratado anterior. Hasta 1818, Francia fue ocupada por 1,2 millones de soldados extranjeros, incluidos unos 200.000 bajo el mando del duque de Wellington , y Francia tuvo que pagar los gastos de alojamiento y raciones, además de las reparaciones. [30] [31] La promesa de recortes de impuestos, prominente en 1814, era impracticable debido a estos pagos. El legado de esto, y el Terror Blanco, dejó a Louis con una oposición formidable. [30]

Los principales ministros de Luis fueron al principio moderados, [32] incluidos Talleyrand, el duque de Richelieu y Élie, duc Decazes ; El propio Luis siguió una política cautelosa. [33] La chambre introuvable , elegida en 1815 , apodada "inalcanzable" por Luis, estaba dominada por una abrumadora mayoría ultrarrealista que rápidamente adquirió la reputación de ser "más realista que el rey". La legislatura expulsó al gobierno de Talleyrand-Fouché y trató de legitimar el Terror Blanco, emitiendo juicios contra los enemigos del estado, despidiendo entre 50.000 y 80.000 funcionarios públicos y destituyendo a 15.000 oficiales del ejército. [30] Richelieu, un emigradoque se había marchado en octubre de 1789, que "no había tenido nada que ver con la nueva Francia", [33] fue nombrado Primer Ministro . La chambre introuvable , mientras tanto, continuó defendiendo agresivamente el lugar de la monarquía y la iglesia, y pidió más conmemoraciones para personajes reales históricos. [a] En el transcurso de la legislatura, los ultrarrealistas comenzaron a fusionar cada vez más su estilo de política con la ceremonia estatal, para disgusto de Louis. [35] Decazes, quizás el ministro más moderado, se movió para detener la politización de la Guardia Nacional (muchos Verdets habían sido reclutados) al prohibir las manifestaciones políticas de la milicia en julio de 1816.[36]

Debido a la tensión entre el gobierno del Rey y la Cámara de Diputados ultrarrealista, esta última comenzó a hacer valer sus derechos. Después de que intentaron obstruir el presupuesto de 1816, el gobierno concedió que la cámara tenía derecho a aprobar los gastos estatales. Sin embargo, no pudieron obtener una garantía del rey de que sus gabinetes representarían a la mayoría en el parlamento. [37]

En septiembre de 1816, Louis disolvió la cámara por sus medidas reaccionarias, y la manipulación electoral resultó en una cámara más liberal en 1816 . Richelieu sirvió hasta el 29 de diciembre de 1818, seguido por Jean-Joseph, marqués Dessolles hasta el 19 de noviembre de 1819, y luego Decazes (en realidad el ministro dominante desde 1818 hasta 1820) [38] [39] hasta el 20 de febrero de 1820. Ésta fue la época que los doctrinarios dominaron la política, esperando reconciliar la monarquía con la Revolución Francesa y el poder con la libertad . Al año siguiente, el gobierno cambió las leyes electorales, recurriendo al gerrymandering., y alterar el derecho al voto para permitir que algunos hombres ricos del comercio y la industria voten, [40] en un intento de evitar que los ultras obtengan la mayoría en las elecciones futuras. Se aclaró y relajó la censura de la prensa, se abrieron a la competencia algunos puestos en la jerarquía militar y se establecieron escuelas mutuas que invadieron el monopolio católico de la educación primaria pública. [41] [42] Decazes purgó a varios prefectos y subprefectos ultrarrealistas y, en elecciones parciales, se eligió a una proporción inusualmente alta de bonapartistas y republicanos, algunos de los cuales fueron respaldados por ultras que recurrían al voto táctico . [38]Los ultras fueron muy críticos con la práctica de dar empleo o ascensos en la función pública a los diputados, mientras el gobierno continuaba consolidando su posición. [43]

En 1820, los liberales de la oposición —que, con los ultras, constituían la mitad de la cámara— demostraron ser ingobernables, y Decazes y el rey buscaban formas de revisar de nuevo las leyes electorales para asegurar una mayoría conservadora más manejable. En febrero de 1820, el asesinato por un bonapartista del duque de Berry , el ultrarreaccionario hijo del ultrarreaccionario hermano y presunto heredero de Luis, el futuro Carlos X , desencadenó la caída del poder de Decazes y el triunfo de los ultras. [44]

Richelieu regresó al poder por un breve intervalo, de 1820 a 1821. La prensa fue censurada más fuertemente, se reintrodujo la detención sin juicio y se prohibió a los líderes doctrinarios , como François Guizot , enseñar en la École Normale Supérieure . [44] [45] Bajo Richelieu, el sufragio se cambió para dar a los electores más ricos un doble voto, a tiempo para las elecciones de noviembre de 1820 . Después de una contundente victoria, se formó un nuevo ministerio Ultra, encabezado por Jean-Baptiste de Villèle , un destacado Ultra que sirvió durante seis años. Los ultras volvieron al poder en circunstancias favorables: la esposa de Berry, la duquesa de Berry, dio a luz a un "niño milagroso", Henri , siete meses después de la muerte del duque; Napoleón murió en Santa Elena en 1821, y su hijo, el duque de Reichstadt , quedó internado en manos austríacas. Figuras literarias, sobre todo Chateaubriand , pero también Hugo , Lamartine , Vigny y Nodier , se unieron a la causa de los ultras. Tanto Hugo como Lamartine se convirtieron más tarde en republicanos, mientras que Nodier lo fue antes. [46] [47] Pronto, sin embargo, Villèle demostró ser casi tan cauteloso como su maestro y, mientras Luis vivió, las políticas abiertamente reaccionarias se mantuvieron al mínimo.

Los ultras ampliaron su apoyo y pusieron fin a la creciente disidencia militar en 1823, cuando la intervención en España, a favor del rey borbón español Fernando VII y contra el gobierno liberal español , fomentó el fervor patriótico popular. A pesar del respaldo británico a la acción militar, la intervención fue vista en general como un intento de recuperar la influencia en España, que había sido perdida por los británicos bajo Napoleón. El ejército expedicionario francés, llamado Cien Mil Hijos de San Luis , estaba dirigido por el duque de Angoulême , hijo del conde de Artois. Las tropas francesas marcharon a Madrid y luego a Cádiz, derrocando a los liberales con pocos combates (abril a septiembre de 1823), y permanecería en España durante cinco años. El apoyo a los ultras entre los votantes ricos se fortaleció aún más repartiendo favores de manera similar a la cámara de 1816, y temores sobre la charbonnerie , el equivalente francés del carbonari . En las elecciones de 1824 , se aseguró otra gran mayoría. [48]

Luis XVIII murió el 16 de septiembre 1824 y fue sucedido por su hermano, el conde de Artois, que tomó el título de Carlos X .

Carlos X [ editar ]

1824-1830: giro conservador [ editar ]

El ascenso al trono de Carlos X, líder de la facción ultrarrealista , coincidió con el control del poder de los ultras en la Cámara de Diputados; así, el ministerio del conde de Villèle pudo continuar. La moderación que Luis había ejercido sobre los ultrarrealistas fue eliminada.

Mientras el país experimentaba un renacimiento cristiano en los años posteriores a la revolución , los ultras trabajaron para elevar el estatus de la Iglesia Católica Romana una vez más. El Concordato de la Iglesia y el Estado del 11 de junio de 1817 se estableció para reemplazar el Concordato de 1801 , pero, a pesar de estar firmado, nunca fue validado. El gobierno de Villèle, bajo la presión de los Chevaliers de la Foi, incluidos muchos diputados, votó la Ley contra el sacrificio en enero de 1825, que castigaba con la muerte el robo de hostias consagradas . La ley era inaplicable y solo se promulgó con fines simbólicos, aunque la aprobación de la ley causó un alboroto considerable, particularmente entre los Doctrinaires.. [49] Mucho más controvertida fue la introducción de los jesuitas, quienes establecieron una red de colegios para jóvenes de élite fuera del sistema universitario oficial. Los jesuitas se destacaron por su lealtad al Papa y dieron mucho menos apoyo a las tradiciones galicanas. Dentro y fuera de la Iglesia tenían enemigos, y el rey terminó su papel institucional en 1828 [50].

La nueva legislación pagó una indemnización a los realistas cuyas tierras habían sido confiscadas durante la Revolución. Aunque esta ley había sido diseñada por Louis, Charles influyó en su aprobación. También se presentó a las cámaras un proyecto de ley para financiar esta compensación, mediante la conversión de la deuda pública (la renta ) de bonos del 5% al 3%, lo que ahorraría al estado 30 millones de francos al año en pagos de intereses. El gobierno de Villèle argumentó que los rentistas habían visto crecer sus rendimientos de manera desproporcionada con respecto a su inversión original, y que la redistribución era justa. La ley final asignó fondos estatales de 988 millones de francos para indemnizaciones ( le milliard des emigrés), financiado con bonos del Estado a un valor de 600 millones de francos al 3% de interés. Se pagaron alrededor de 18 millones de francos al año. [51] Los beneficiarios inesperados de la ley fueron alrededor de un millón de propietarios de biens nationaux , las antiguas tierras confiscadas, cuyos derechos de propiedad fueron ahora confirmados por la nueva ley, lo que llevó a un fuerte aumento de su valor. [52]

En 1826, Villèle presentó un proyecto de ley que restablecía la ley de primogenitura , al menos para los propietarios de grandes propiedades, a menos que eligieran lo contrario. Los liberales y la prensa se rebelaron, al igual que algunos ultras disidentes, como Chateaubriand. Sus vociferantes críticas llevaron al gobierno a presentar un proyecto de ley para restringir la prensa en diciembre, habiendo retirado en gran medida la censura en 1824. Esto solo enardeció aún más a la oposición y el proyecto de ley fue retirado. [53]

El gabinete de Villèle enfrentó una presión creciente en 1827 de la prensa liberal, incluido el Journal des débats , que patrocinó los artículos de Chateaubriand. Chateaubriand, el más destacado de los ultras anti-Villèle, se había combinado con otros opositores a la censura de prensa (una nueva ley la había vuelto a imponer el 24 de julio de 1827) para formar la Société des amis de la liberté de la presse ; Choiseul-Stainville , Salvandy y Villemain estuvieron entre los contribuyentes. [54] Otra sociedad influyente fue la Société Aide-toi, le ciel t'aidera, que trabajó dentro de los límites de la legislación que prohíbe las reuniones no autorizadas de más de 20 miembros. El grupo, envalentonado por la creciente ola de oposición, tenía una composición más liberal (asociada con Le Globe ) e incluía a miembros como Guizot , Rémusat y Barrot . [55] Se enviaron panfletos que eludían las leyes de censura, y el grupo brindó asistencia organizativa a los candidatos liberales contra los funcionarios estatales progubernamentales en las elecciones de noviembre de 1827 . [56]

En abril de 1827, el Rey y Villèle se enfrentaron a una Guardia Nacional rebelde . La guarnición que Charles revisó, con órdenes de expresar deferencia al rey pero desaprobación de su gobierno, en cambio gritó comentarios despectivos contra los jesuitas a su devotamente católica sobrina y nuera, Marie Thérèse, Madame la Dauphine . Villèle sufrió un trato peor, ya que los oficiales liberales llevaron a las tropas a protestar en su oficina. En respuesta, la Guardia se disolvió. [56] Continuaron proliferando panfletos, que incluían acusaciones en septiembre de que Carlos, en un viaje a Saint-Omer , estaba en connivencia con el Papa y planeaba restablecer el diezmo, y había suspendido la Carta bajo la protección de un ejército de guarnición leal. [57]

En el momento de la elección, los realistas moderados (constitucionalistas) también estaban comenzando a volverse contra Charles, al igual que la comunidad empresarial, en parte debido a una crisis financiera en 1825, que culparon a la ley de indemnización del gobierno. [58] [59] Hugo y varios otros escritores, descontentos con la realidad de la vida bajo Carlos X, también comenzaron a criticar al régimen. [60] En preparación para el 30 de septiembre de registro de corte para la elección, los comités de oposición trabajaba furiosamente para obtener el mayor número posible de votantes inscritos, la lucha contra las acciones de los prefectos, who began removing certain voters who had failed to provide up-to-date documents since the 1824 election. 18,000 voters were added to the 60,000 on the first list; despite préfect attempts to register those who met the franchise and were supporters of the government, this can mainly be attributed to opposition activity.[61] Organization was mainly divided behind Chateaubriand's Friends and the Aide-toi, which backed liberals, constitutionnels, and the contre-opposition (constitutional monarchists).[62]

The new chamber did not result in a clear majority for any side. Villèle's successor, the vicomte de Martignac, who began his term in January 1828, tried to steer a middle course, appeasing liberals by loosening press controls, expelling Jesuits, modifying electoral registration, and restricting the formation of Catholic schools.[63] Charles, unhappy with the new government, surrounded himself with men from the Chevaliers de la Foi and other ultras, such as the Prince de Polignac and La Bourdonnaye. Martignac was deposed when his government lost a bill on local government. Charles and his advisers believed a new government could be formed with the support of the Villèle, Chateaubriand, and Decazes monarchist factions, but chose a chief minister, Polignac, in November 1829 who was repellant to the liberals and, worse, Chateaubriand. Though Charles remained nonchalant, the deadlock led some royalists to call for a coup, and prominent liberals for a tax strike.[64]

At the opening of the session in March 1830, the King delivered a speech that contained veiled threats to the opposition; in response, 221 deputies (an absolute majority) condemned the government, and Charles subsequently prorogued and then dissolved parliament. Charles retained a belief that he was popular amongst the unenfranchised mass of the people, and he and Polignac chose to pursue an ambitious foreign policy of colonialism and expansionism, with the assistance of Russia. France had intervened in the Mediterranean a number of times after Villèle's resignation, and expeditions were now sent to Greece and Madagascar. Polignac also initiated French colonization in Algeria; victory was announced over the Dey of Algiers in early July. Plans were drawn up to invade Belgium, which was shortly to undergo its own revolution. However, foreign policy did not prove sufficient to divert attention from domestic problems.[65][66]

Charles's dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies, his July Ordinances which set up rigid control of the press, and his restriction of suffrage resulted in the July Revolution of 1830. The major cause of the regime's downfall, however, was that, while it managed to keep the support of the aristocracy, the Catholic Church and even much of the peasantry, the ultras' cause was deeply unpopular outside of parliament and with those who did not hold the franchise,[67] especially the industrial workers and the bourgeoisie.[68] A major reason was a sharp rise in food prices, caused by a series of bad harvests 1827–1830. Workers living on the margin were very hard-pressed, and angry that the government paid little attention to their urgent needs.[69]

Charles abdicated in favor of his grandson, the Comte de Chambord, and left for England. However, the liberal, bourgeois-controlled Chamber of Deputies refused to confirm the Comte de Chambord as Henri V. In a vote largely boycotted by conservative deputies, the body declared the French throne vacant, and elevated Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, to power.

1827–1830: Tensions[edit]

There is still considerable debate among historians as to the actual cause of the downfall of Charles X. What is generally conceded, though, is that between 1820 and 1830, a series of economic downturns combined with the rise of a liberal opposition within the Chamber of Deputies, ultimately felled the conservative Bourbons.[70]

Between 1827 and 1830, France faced an economic downturn, industrial and agricultural, that was possibly worse than the one that sparked the Revolution. A series of progressively worsening grain harvests in the late 1820s pushed up the prices on various staple foods and cash crops.[71] In response, the rural peasantry throughout France lobbied for the relaxation of protective tariffs on grain to lower prices and ease their economic situation. However, Charles X, bowing to pressure from wealthier landowners, kept the tariffs in place. He did so based upon the Bourbon response to the "Year Without a Summer" in 1816, during which Louis XVIII relaxed tariffs during a series of famines, caused a downturn in prices, and incurred the ire of wealthy landowners, who were the traditional source of Bourbon legitimacy. Thus, between 1827 and 1830, peasants throughout France faced a period of relative economic hardship and rising prices.

At the same time, international pressures, combined with weakened purchasing power from the provinces, led to decreased economic activity in urban centers. This industrial downturn contributed to the rising poverty levels among Parisian artisans. Thus, by 1830, multiple demographics had suffered from the economic policies of Charles X.

While the French economy faltered, a series of elections brought a relatively powerful liberal bloc into the Chamber of Deputies. The 17-strong liberal bloc of 1824 grew to 180 in 1827, and 274 in 1830. This liberal majority grew increasingly dissatisfied with the policies of the centrist Martignac and the ultra-royalist Polignac, seeking to protect the limited protections of the Charter of 1814. They sought both the expansion of the franchise, and more liberal economic policies. They also demanded the right, as the majority bloc, to appoint the Prime Minister and the Cabinet.

Also, the growth of the liberal bloc within the Chamber of Deputies corresponded roughly with the rise of a liberal press within France. Generally centered around Paris, this press provided a counterpoint to the government's journalistic services, and to the newspapers of the right. It grew increasingly important in conveying political opinions and the political situation to the Parisian public, and can thus be seen as a crucial link between the rise of the liberals and the increasingly agitated and economically suffering French masses.

By 1830, the Restoration government of Charles X faced difficulties on all sides. The new liberal majority clearly had no intention of budging in the face of Polignac's aggressive policies. The rise of a liberal press within Paris which outsold the official government newspaper indicated a general shift in Parisian politics towards the left. And yet, Charles' base of power was certainly toward the right of the political spectrum, as were his own views. He simply could not yield to the growing demands from within the Chamber of Deputies. The situation would soon come to a head.

1830: The July Revolution[edit]

The Charter of 1814 had made France a constitutional monarchy. While the king retained extensive power over policy-making, as well as the sole power of the Executive, he was, nonetheless, reliant upon the Parliament to accept and pass his legal decrees.[72] The Charter also fixed the method of election of the Deputies, their rights within the Chamber of Deputies, and the rights of the majority bloc. Thus, in 1830, Charles X faced a significant problem. He could not overstep his constitutional bounds, and yet, he could not preserve his policies with a liberal majority within the Chamber of Deputies. Stark action was required. A final no-confidence vote by the liberals, in March 1830, spurred the king into action, and he set about to alter the Charter of 1814 by decree. These decrees, known as the "Four Ordinances", dissolved the Chamber of Deputies, suspended the liberty of the press, excluded the commercial middle-class from future elections, and called for new elections.[73]

Opinion was outraged. On 10 July 1830, before the king had even made his declarations, a group of wealthy, liberal journalists and newspaper proprietors, led by Adolphe Thiers, met in Paris to decide upon a strategy to counter Charles X. It was decided then, nearly three weeks before the Revolution, that in the event of Charles' expected proclamations, the journalistic establishment of Paris would publish vitriolic criticisms of the king's policies in an attempt to mobilise the masses. Thus, when Charles X made his declarations on the 25th of July 1830, the liberal journalism machine mobilised, publishing articles and complaints decrying the despotism of the king's actions.[74]

The urban mobs of Paris also mobilised, driven by patriotic fervour and economic hardship, assembling barricades and attacking the infrastructure of Charles X. Within days, the situation escalated beyond the ability of the monarchy to control it. As the Crown moved to shut down liberal periodicals, the radical Parisian masses defended those publications. They also launched attacks against pro-Bourbon presses, and paralysed the coercive apparatus of the monarchy. Seizing the opportunity, the liberals in Parliament began drafting resolutions, complaints, and censures against the king. The king finally abdicated on 30 July 1830. Twenty minutes later, his son, Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême, who had nominally succeeded as Louis XIX, also abdicated. The Crown nominally then fell upon the son of Louis Antoine's younger brother, Charles X's grandson, who was in line to become Henri V. However, the newly empowered Chamber of Deputies declared the throne vacant, and on 9 August, elevated Louis-Philippe, to the throne. Thus, the July Monarchy began.[75]

Louis-Philippe and the House of Orléans[edit]

Louis-Philippe ascended the throne on the strength of the July Revolution of 1830, and ruled, not as "King of France" but as "King of the French", marking the shift to national sovereignty. The Orléanists remained in power until 1848. Following the ousting of the last king to rule France during the February 1848 Revolution, the French Second Republic was formed with the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as President (1848–1852). In the French coup of 1851, Napoleon declared himself Emperor Napoleon III of the Second Empire, which lasted from 1852 to 1870.

Political parties under Restoration[edit]

Political parties saw substantial changes of alignment and membership under the Restoration. The Chamber of Deputies oscillated between repressive ultra-royalist phases and progressive liberal phases. Opponents of the monarchy were absent from the political scene, because of the repression of the White Terror. Individuals of influence who had different visions of the French constitutional monarchy clashed.[76][77]

All parties remained fearful of the common people, whom Adolphe Thiers later referred to by the term "cheap multitude". Their political sights were set on a favoritism of class. Political changes in the Chamber were due to abuse by the majority tendency, involving a dissolution and then an inversion of the majority, or critical events; for example, the assassination of the Duc de Berry in 1820.

Disputes were a power struggle between the powerful (royalty against deputies) rather than a fight between royalty and populism. Although the deputies claimed to defend the interests of the people, most had an important fear of common people, of innovations, of socialism and even of simple measures, such as the extension of voting rights.

The principal political parties during the Restoration are described below.

Ultra-royalists[edit]

The Ultra-royalists wished for a return to the Ancien Régime which prevailed before 1789: absolute monarchy, domination by the nobility, and the monopoly of politics by "devoted Christians". They were anti-Republican, anti-democratic, and preached Government on High. Although they tolerated vote censitaire, a form of democracy limited to those paying taxes above a high threshold, they found the Charter of 1814 to be too revolutionary. They wanted a re-establishment of privileges, a major political role for the Catholic Church, and a politically active, rather than ceremonial, king: Charles X.[78]

Prominent ultra-royalist theorists were Louis de Bonald and Joseph de Maistre. Their parliamentary leaders were François Régis de La Bourdonnaye, comte de La Bretèche and, in 1829, Jules de Polignac. The main royalist newspapers were La Quotidienne and La Gazette, supplemented by the Drapeau Blanc, named after the Bourbon white flag, and the Oriflamme, named after the battle standard of France.

Doctrinaires[edit]

The Doctrinaires were mostly rich and educated middle-class men: lawyers, senior officials of the Empire, and academics. They feared the triumph of the aristocracy, as much as that of the democrats. They accepted the Royal Charter as a guarantee of freedom and civil equality which nevertheless reined in the ignorant and excitable masses. Ideologically they were classical liberals who formed the centre-right of the Restoration's political spectrum: they upheld both capitalism and Catholicism, and attempted to reconcile parliamentarism (in an elite, wealth-based form) and monarchism (in a constitutional, ceremonial form), while rejecting both the absolutism and clericalism of the Ultra-Royalists, and the universal suffrage of the liberal left and republicans. Important personalities were Pierre Paul Royer-Collard, François Guizot, and the count of Serre. Their newspapers were Le Courrier français and Le Censeur.[79]

Liberal Left[edit]

The left-leaning liberals were mostly of the petty-bourgeoisie (lower middle classes): doctors and lawyers, men of law, and, in rural constituencies, merchants and traders of national goods. Electorally they benefitted from the slow emergence of a new middle-class elite, due to the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Some of them accepted the principle of monarchy, in a strictly ceremonial and parliamentary form, while others were moderate republicans. Constitutional issues aside, they agreed on seeking to restore the democratic principles of the French Revolution, such as the weakening of clerical and aristocratic power, and therefore thought the constitutional Charter was not suffiçiently democratic, and disliked the peace treaties of 1815, the White Terror and the return to pre-eminence of clergy and of nobility. They wished to lower the taxable quota to support the middle-class as a whole, to the detriment of the aristocracy, and this they supported universal suffrage or at least a wide opening-up of the electoral system to the modest middle-classes such as farmers and craftsmen. Important personalities were parliamentary monarchist Benjamin Constant, officer of the Empire Maximilien Sebastien Foy, republican lawyer Jacques-Antoine Manuel, and the Marquis de Lafayette. Their newspapers were La Minerve, Le Constitutionnel, and Le Globe.[80]

Republicans and Socialists[edit]

The only active Republicans were on the left, based among the workers. Workers had no vote and were not listened to. Their demonstrations were repressed or diverted, causing, at most, a reinforcement of parliamentarism, which did not mean democratic evolution, only wider taxation. For some, such as Blanqui, revolution seemed the only solution. Garnier-Pagès, and Louis-Eugène and Éléonore-Louis Godefroi Cavaignac considered themselves to be Republicans, while Cabet and Raspail were active as socialists. Saint-Simon was also active during this period, and made direct appeals to Louis XVIII before his death in 1824.[81]

Religion[edit]

By 1800 the Catholic Church was poor, dilapidated and disorganised, with a depleted and aging clergy. The younger generation had received little religious instruction, and was unfamiliar with traditional worship.[82] However, in response to the external pressures of foreign wars, religious fervour was strong, especially among women.[83] Napoleon's Concordat of 1801 provided stability and ended attacks on the Church.

With the Restoration, the Catholic Church again became the state religion, supported financially and politically by the government. Its lands and financial endowments were not returned, but the government paid salaries and maintenance costs for normal church activities. The bishops regained control of Catholic affairs. The aristocracy before the Revolution was lukewarm to religious doctrine and practice, but the decades of exile created an alliance of throne and altar. The royalists who returned were much more devout, and much more aware of their need for a close alliance with the Church. They had discarded fashionable skepticism and now promoted the wave of Catholic religiosity that was sweeping Europe, with a new reverence for the Virgin Mary, the saints, and popular religious rituals such as praying the rosary. Devotion was far stronger and more visible in rural areas than in Paris and other cities. The population of 32 million included about 680,000 Protestants and 60,000 Jews, who were extended toleration. The anti-clericalism of Voltaire and the Enlightenment had not disappeared, but it was in abeyance.[84]

At the elite level, there was a dramatic change in intellectual climate from intellectual classicism to passionate romanticism. An 1802 book by François-René de Chateaubriand entitled Génie du christianisme ("The Genius of Christianity") had an enormous influence in reshaping French literature and intellectual life, emphasising the centrality of religion in creating European high culture. Chateaubriand's book:

- did more than any other single work to restore the credibility and prestige of Christianity in intellectual circles and launched a fashionable rediscovery of the Middle Ages and their Christian civilisation. The revival was by no means confined to an intellectual elite, however, but was evident in the real, if uneven, rechristianisation of the French countryside.[85]

Economy[edit]

With the restoration of the Bourbons in 1814, the reactionary aristocracy with its disdain for entrepreneurship returned to power. British goods flooded the market, and France responded with high tariffs and protectionism to protect its established businesses, especially handcrafts and small-scale manufacturing such as textiles. The tariff on iron goods reached 120%.[86] Agriculture had never needed protection, but now demanded it due to the lower prices of imported foodstuffs, such as Russian grain. French winegrowers strongly supported the tariff – their wines did not need it, but they insisted on a high tariff on the import of tea. One agrarian deputy explained: "Tea breaks down our national character by converting those who use it often into cold and stuffy Nordic types, while wine arouses in the soul that gentle gaiety that gives Frenchmen their amiable and witty national character."[87] The French government falsified official statistics to claim that exports and imports were growing – actually there was stagnation, and the economic crisis of 1826-29 disillusioned the business community and readied them to support the revolution in 1830.[88]

Art and literature[edit]

Romanticism reshaped art and literature.[89] It stimulated the emergence of a wide new middle class audience.[90]Among the most popular works were:

- Les Misérables, Victor Hugo's novel which is set in the 20 years after Napoleon's Hundred Days

- The Red and the Black, Stendhal's novel set in the final years of the regime

- La Comédie humaine, a sequence of almost 100 novels and plays by Honoré de Balzac, set during the Restoration and the July Monarchy

Paris[edit]

The city grew slowly in population from 714,000 in 1817 to 786,000 in 1831. During the period Parisians saw the first public transport system, the first gas street lights, and the first uniformed Paris policemen. In July 1830, a popular uprising in the streets of Paris brought down the Bourbon monarchy.[91]

Memory and historical evaluation[edit]

After two decades of war and revolution, the restoration brought peace and quiet, and general prosperity. Gordon Wright says, "Frenchmen were, on the whole, well governed, prosperous, contented during the 15-year period; one historian even describes the restoration era as 'one of the happiest periods in [France's] history.[92]

France had recovered from the strain and disorganization, the wars, the killings, the horrors, of two decades of disruption. It was at peace throughout the period. It paid a large war indemnity to the winners, but managed to finance that without distress; the occupation soldiers left peacefully. France's population increased by 3 million, and prosperity was strong from 1815 to 1825, with the depression of 1825 caused by bad harvests. The national credit was strong, there was significant increase in public wealth, and the national budget showed a surplus every year. In the private sector, banking grew dramatically, making Paris a world center for finance, along with London. The Rothschild family was world-famous, with the French branch led by James Mayer de Rothschild (1792–1868). The communication system was improved, as roads were upgraded, canals were lengthened, and steamboat traffic became common. Industrialization was delayed in comparison to Britain and Belgium. The railway system had yet to make an appearance. Industry was heavily protected with tariffs, so there was little demand for entrepreneurship or innovation.[93][94]

Culture flourished with the new romantic impulses. Oratory was highly regarded, and sophisticated debate flourished. Châteaubriand and Madame de Stael (1766-1817) enjoyed Europe-wide reputations for their innovations in romantic literature. She made important contributions to political sociology, and the sociology of literature.[95] History flourished; François Guizot, Benjamin Constant and Madame de Staël drew lessons from the past to guide the future.[96] The paintings of Eugène Delacroix set the standards for romantic art. Music, theater, science, and philosophy all flourished.[97] The higher learning flourished at the Sorbonne. Major new institutions gave France world leadership in numerous advanced fields, as typified by the École Nationale des Chartes (1821) for historiography, the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in 1829 for innovative engineering; and the École des Beaux-Arts for the fine arts, reestablished in 1830.[98]

Charles X repeatedly exacerbated internal tensions, and tried to neutralize his enemies with repressive measures. They totally failed and forced him into exile for the third time. However the government's handling of foreign affairs was a success. France kept a low profile, and Europe forgot its animosities. Louis and Charles had little interest in foreign affairs, so France played only minor roles. For example, it helped the other powers deal with Greece and Turkey. Charles X mistakenly thought that foreign glory would cover domestic frustration, so he made an all-out effort to conquer Algiers in 1830. He sent a massive force of 38,000 soldiers and 4,500 horses carried by 103 warships and 469 merchant ships. The expedition was a dramatic military success.[99] It even paid for itself with captured treasures. The episode launched the second French colonial empire, but it did not provide desperately needed political support for the King at home.[100]

Restoration in recent popular culture[edit]

The French historical film Jacquou le Croquant, directed by Laurent Boutonnat and starring Gaspard Ulliel and Marie-Josée Croze, is based on the Bourbon Restoration.

See also[edit]

- French Restoration style

- Pierre Louis Jean Casimir de Blacas

- Mathieu de Montmorency

- French Empire mantel clock

- French monarchs family tree

- France in the long nineteenth century

Notes[edit]

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 282 This included blocking the budget over plans to guarantee bonds on the sale of 400,000 hectares of forest previously owned by the church, reintroducing prohibition of divorce, demanding the death penalty for individuals found with the tricolore, and attempting to hand civil registers back to the church.[34]

References[edit]

- ^ a b de Sauvigny, Guillaume de Bertier. The Bourbon Restoration (1966)

- ^ John W. Rooney, Jr. and Alan J. Reinerman, "Continuity: French Foreign Policy Of The First Restoration" Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750-1850: Proceedings (1986), Vol. 16, p275-288.

- ^ Davies 2002, pp. 47–54.

- ^ de Sauvigny, Guillaume de Bertier. The Bourbon Restoration (1966)

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 296.

- ^ John B. Wolf, France: 1814–1919: The Rise of a liberal-Democratic Society (2nd ed. 1962 pp 4–27

- ^ Peter McPhee, A social history of France 1780–1880 (1992) pp 93–173

- ^ Christophe Charle, A Social History of France in the 19th Century (1994) pp 7–27

- ^ James McMillan, "Catholic Christianity in France from the Restoration to the separation of church and state, 1815–1905." in Sheridan Gilley and Brian Stanley, eds., The Cambridge history of Christianity (2014) 8: 217–232

- ^ H.C. Barnard (1969). Education and French Revolution. Cambridge University press. p. 223.

- ^ Gordon K. Anderson, "Old Nobles and Noblesse d'Empire, 1814–1830: In Search of a Conservative Interest in Post-Revolutionary France." French History 8.2 (1994): 149-166.

- ^ Wolf, France: 1814–1919 pp 9, 19–21

- ^ The Charter of 1814, Public Law of the French: Article 1

- ^ The Charter of 1814, Form of the Government of the King: Article 14

- ^ Price 2008, p. 93.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 329.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 330–331.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 271.

- ^ a b c Furet 1995, p. 272.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 332.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 332–333.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 333.

- ^ Ingram 1998, p. 43

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 334.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 278.

- ^ Alexander 2003, pp. 32, 33.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 335.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 279.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 336.

- ^ a b c Tombs 1996, p. 337.

- ^ EM staff 1918, p. 161.

- ^ Bury 2003, p. 19.

- ^ a b Furet 1995, p. 281.

- ^ Alexander 2003, pp. 37, 38.

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 39.

- ^ Alexander 2003, pp. 54, 58.

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 36.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 338.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 289.

- ^ Furet 1995, pp. 289, 290.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 290.

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 99.

- ^ Alexander 2003, p. 81.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 339.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 291.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 340.

- ^ Furet 1995, p. 295.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 340–341; Crawley 1969, p. 681

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 341–342.

- ^ BN (Barbara Neave, comtesse de Courson) (1879). The Jesuits: their foundation and history. p. 305.

- ^ Price 2008, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 344–345.

- ^ Kent 1975, pp. 81–83.

- ^ Kent 1975, pp. 84–89.

- ^ a b Tombs 1996, p. 345.

- ^ Kent 1975, p. 111.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 344.

- ^ Kent 1975, pp. 107–110.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Kent 1975, p. 116.

- ^ Kent 1975, p. 121.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 348.

- ^ Tombs 1996, p. 348–349.

- ^ Tombs 1996, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Bury 2003, pp. 39, 42.

- ^ Bury 2003, p. 34.

- ^ Hudson 1973, pp. 182, 183

- ^ David H, Pinkney, "A new look at the French revolution of 1830." Review of Politics 23.4 (1961): 490-506.

- ^ Pilbeam 1999, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Bury 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Bury, France, 1814-1940 (1949) pp 33-44.

- ^ Marc Leepson (2011). Lafayette: Lessons in Leadership from the Idealist General. St. Martin's Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780230105041.

- ^ Paul W. Schroeder (1996). The Transformation of European Politics, 1763-1848. pp. 666–670. ISBN 9780198206545.

- ^ Sally Waller (2002). France in Revolution, 1776-1830. Heinemann. pp. 134–35. ISBN 9780435327323.

- ^ Frederick Artz, . France Under the Bourbon Restoration, 1814–1830 (1931) pp 9=99.

- ^ J.P.T. Bury, France, 1814-1940 (1949) pp 18-44.

- ^ Nora Eileen Hudson, Ultra-royalism and the French restoration (1936).

- ^ Douglas Johnson, Guizot: aspects of French history, 1787-1874 (1963).

- ^ Dennis Wood, Benjamin Constant: A Biography (1993).

- ^ Kirkup 1892, p. 21.

- ^ History Review 68 (2010): 16-21.

- ^ Robert Tombs, France: 1814-1914 (1996) p 241

- ^ Frederick B. Artz, France under the Bourbon Restoration, 1814-1830 (1931) pp 99-171.

- ^ James McMillan, "Catholic Christianity in France from the Restoration to the separation of church and state, 1815-1905." in Sheridan Gilley and Brian Stanley, eds., The Cambridge history of Christianity (2014) 8: 217-232

- ^ François Caron, An economic history of modern France (1979) pp 95-96.

- ^ Gordon Wright, France in Modern Times (1995) p. 147

- ^ Alan S. Milward and S. B. Saul, Economic Development of Continental Europe, 1780-1870 (1979) pp 307-64.

- ^ Stewart, Restoration Era (1968), pp 83-87.

- ^ James Smith Allen, Popular French Romanticism: Authors, Readers, and Books in the 19th Century (1981)

- ^ Colin Jones, Paris: The Biography of a City (2006) pp 263-99.

- ^ Gordon Wright, France and Modern Times (5th ed. 1995) p 105, quoting Bertier de Sauvigny.

- ^ J.P.T. Bury, France 1814 – 1940 (1949) pp 41-42.

- ^ J. H. Clapham, The Economic Development of France and Germany 1815-1914 (1936) pp 53-81, 104-7, 121-27.

- ^ Germaine de Stael and Monroe Berger, Politics, Literature, and National Character (2000)

- ^ Lucian Robinson, "Accounts of early Christian history in the thought of François Guizot, Benjamin Constant and Madame de Staël 1800–c. 1833." History of European Ideas 43#6 (2017): 628-648.

- ^ Michael Marrinan, Romantic Paris: histories of a cultural landscape, 1800-1850 (2009).

- ^ Pierre Bourdieu (1998). The State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of Power. Stanford UP. pp. 133–35. ISBN 9780804733465.

- ^ Nigel Falls, "The Conquest of Algiers," History Today (2005) 55#10 pp 44-51.

- ^ Bury, France 1814 – 1940 (1949) pp 43-44.

Further reading[edit]

- Artz, Frederick B. "The Electoral System in France during the Bourbon Restoration, 1815-30." Journal of Modern History 1.2 (1929): 205–218. online

- Artz, Frederick (1934). Reaction and Revolution, 1814–1832; covers all of Europe

- Artz, Frederick. 1931. France Under the Bourbon Restoration, 1814–1830 (Harvard University Press, 1931) online free; the main scholarly history

- Beach, Vincent W. (1971) Charles X of France: His Life and Times (Boulder: Pruett, 1971) 488 pp

- Brogan, D. W. "The French Restoration: 1814-1830" History Today (Jan 1956) 6#1 pp 28-36; part 2, (Feb 1956), 6#2, pp 104-109..

- Bury, J.P.T. (2003). France, 1814–1940. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-31600-6.

- Charle, Christophe. (1994) A Social History of France in the 19th Century (1994) pp 1–52

- Collingham, Hugh A. C. (1988). The July Monarchy: A Political History of France, 1830–1848. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-02186-3.

- Counter, Andrew J. "A Nation of Foreigners: Chateaubriand and Repatriation." Nineteenth-Century French Studies 46.3 (2018): 285–306. online

- Crawley, C. W. (1969). The New Cambridge Modern History. Volume IX: War and Peace in an Age of Upheaval, 1793–1830. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. ISBN 978-0-521-04547-6.

- Davies, Peter (2002). The Extreme Right in France, 1789 to the Present: From De Maistre to Le Pen. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23982-6.

- Fenby, Jonathan. "Return of the King." History Today (Oct 2015) 65#10 pp 49–54; Very well illustrated popular history.

- Fortescue, William. (1988) Revolution and Counter-revolution in France, 1815-1852 (Blackwell, 1988).

- Fozzard, Irene. "The Government and the Press in France, 1822 to 1827." English Historical Review 66.258 (1951): 51–66. online

- Furet, François. Revolutionary France 1770-1880 (1995), pp 269–325. survey of political history by leading scholar

- Hall, John R. The Bourbon Restoration (1909) online free

- Haynes, Christine. Our Friends the Enemies. The Occupation of France after Napoleon (Harvard University Press, 2018) online reviews

- Hudson, Nora Eileen (1973). Ultra-Royalism and the French Restoration. Octagon Press. ISBN 0-374-94027-4.

- Jardin, Andre, and Andre-Jean Tudesq. Restoration and Reaction 1815–1848 (1988)

- Kent, Sherman (1975). The Election of 1827 in France. Harvard UP. ISBN 0-674-24321-8.

- Kelly, George A. "Liberalism and aristocracy in the French Restoration." Journal of the History of Ideas 26.4 (1965): 509–530. Online

- Kieswetter, James K. "The Imperial Restoration: Continuity in Personnel and Policy under Napoleon I and Louis XVIII." Historian 45.1 (1982): 31–46. online

- Knapton, Ernest John. (1934) "Some Aspects of the Bourbon Restoration of 1814." Journal of Modern History (1934) 6#4 pp: 405–424. in JSTOR

- Kroen, Sheryl T. (Winter 1998). "Revolutionizing Religious Politics during the Restoration". French Historical Studies. 21 (1): 27–53. doi:10.2307/286925. JSTOR 286925.

- Lucas-Dubreton, J. The Restoration and the July Monarchy (1929) pp 1–173.

- Merriman, John M. ed. 1830 in France (1975). 7 long articles by scholars.

- Newman, Edgar Leon (March 1974). "The Blouse and the Frock Coat: The Alliance of the Common People of Paris with the Liberal Leadership and the Middle Class during the Last Years of the Bourbon Restoration". The Journal of Modern History. 46 (1): 26–59. doi:10.1086/241164. S2CID 153370679.

- Newman, Edgar Leon, and Robert Lawrence Simpson. Historical Dictionary of France from the 1815 Restoration to the Second Empire (Greenwood Press, 1987) online edition

- Pilbeam, Pamela (June 1989). "The Economic Crisis of 1827–32 and the 1830 Revolution in Provincial France". The Historical Journal. 32 (2): 319–338. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00012176.

- Pilbeam, Pamela (June 1982). "The Growth of Liberalism and the Crisis of the Bourbon Restoration, 1827–1830". The Historical Journal. 25 (2): 351–366. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00011596.

- Pilbeam, Pamela (1999). Alexander, Martin S. (ed.). French History Since Napoleon. Arnold. ISBN 0-340-67731-7.

- Pinkney, David. The French Revolution of 1830 (1972)

- Price, Munro. (2008). The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions. Pan. ISBN 978-0-330-42638-1.

- Rader, Daniel L. (1973). The Journalists and the July Revolution in France. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 90-247-1552-0.

- de Sauvigny, Guillaume de Bertier. The Bourbon Restoration (1966)

- Tombs, Robert (1996). France 1814–1914. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-49314-5.

- Stewart, John Hall. The restoration era in France, 1814-1830 (1968) 223pp

- Wolf, John B. (1940) France: 1815 to the Present (1940) online free pp 1–75.

Historiography[edit]

- Alexander, Robert (2003). Re-Writing the French Revolutionary Tradition: Liberal Opposition and the Fall of the Bourbon Monarchy. Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-80122-2.

- Haynes, Christine. Our Friends the Enemies. The Occupation of France after Napoleon (Harvard University Press, 2018) online reviews on H-DIPLO 2020

- Haynes, Christine. "Remembering and Forgetting the First Modern Occupations of France,” Journal of Modern History 88:3 (2016): 535-571 online

- Sauvigny, G. de Bertier de (Spring 1981). "The Bourbon Restoration: One Century of French Historiography". French Historical Studies. 12 (1): 41–67. doi:10.2307/286306. JSTOR 286306.

Primary sources[edit]

- Anderson, F.M. (1904). The constitutions and other select documents illustrative of the history of France, 1789–1901. The H. W. Wilson company 1904., complete text online

- Collins, Irene, ed. Government and society in France, 1814-1848 (1971) pp 7–87. Primary sources translated into English.

- Lindsann, Olchar E. ed. Liberté, Vol. II: 1827-1847 (2012) original documents in English translation regarding politics, literature, history, philosophy, and art. online free; 430pp

- Stewart, John Hall ed. The Restoration Era in France, 1814-1830 (1968) 222pp; excerpts from 68 primary sources, plus 87pp introduction

External links[edit]

- Media related to Restauration period at Wikimedia Commons

Coordinates: 48°49′N 2°29′E / 48.817°N 2.483°E / 48.817; 2.483