| Greenwich Village | |

|---|---|

| |

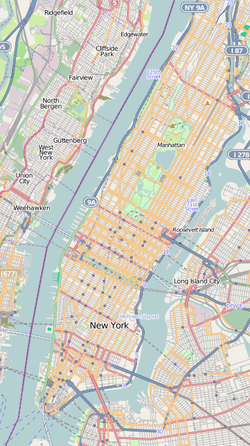

Ubicación en la ciudad de Nueva York | |

| Coordenadas: 40.734 ° N 74.002 ° W Coordenadas : 40.734 ° N 74.002 ° W40°44′02″N 74°00′07″W / 40°44′02″N 74°00′07″W / | |

| País | |

| Expresar | |

| Ciudad | Nueva York |

| Ciudad | Manhattan |

| Distrito Comunitario | Manhattan 2 [1] |

| Nombrado para | Groenwijck (distrito verde) |

| Área[2] | |

| • Total | 0,75 km 2 (0,289 millas cuadradas) |

| Población[2] | |

| • Total | 22,785 |

| • Densidad | 30.000 / km 2 (79.000 / millas cuadradas) |

| Demonym (s) | Aldeano |

| Ciencias económicas[2] | |

| • Ingresos medios | $ 119,728 |

| Zona horaria | UTC-5 ( Este ) |

| • Verano ( DST ) | UTC − 4 ( EDT ) |

| Códigos ZIP | 10003, 10011, 10012, 10014 [2] |

| Códigos de área | 212, 332, 646 y 917 |

Distrito histórico de Greenwich Village | |

453–461 Sixth Avenue en el distrito histórico | |

| Localización | Límites: norte: W 14th St; sur: Houston St; al oeste: río Hudson; este: Broadway |

| Coordenadas | 40°44′2″N 74°0′4″W / 40.73389 ° N 74.00111 ° W |

| Estilo arquitectónico | varios |

| NRHP referencia No. | 79001604 [3] |

| Fechas significativas | |

| Agregado a NRHP | 19 de junio de 1979 |

| NYCL designado | Distrito inicial: 29 de abril de 1969 Prórroga: 2 de mayo de 2006 Segunda prórroga: 22 de junio de 2010 |

Greenwich Village ( / ɡ r ɛ n ɪ tʃ / GREN -itch , / ɡ r ɪ n - / GRIN - , / - ɪ del dʒ / -ij ) [4] es un barrio en el lado oeste de Manhattan , en Nueva York, delimitada por 14th Street al norte, Broadway al este, Houston Street al sur y el río Hudsonhacia el oeste. Greenwich Village también contiene varias subsecciones, incluido el West Village al oeste de Seventh Avenue y el Meatpacking District en la esquina noroeste de Greenwich Village.

Su nombre proviene de Groen wijck , holandés para "Distrito Verde". [5] [a] En el siglo XX, Greenwich Village era conocido como un paraíso para los artistas, la capital de Bohemia , la cuna del movimiento LGBT moderno y el lugar de nacimiento de la costa este de los movimientos Beat y de la contracultura de los sesenta . Greenwich Village contiene Washington Square Park , así como dos de las universidades privadas de Nueva York, la Universidad de Nueva York (NYU) y The New School . [7] [8]

Greenwich Village es parte del Distrito 2 de la Comunidad de Manhattan y está patrullado por el sexto recinto del Departamento de Policía de la ciudad de Nueva York . [1] Greenwich Village ha experimentado una amplia gentrificación y comercialización; [9] Los cuatro códigos postales que constituyen el Village - 10011, 10012, 10003 y 10014 - se clasificaron entre los diez más caros de los Estados Unidos según el precio medio de la vivienda en 2014, según Forbes , [10] con propiedad residencial los precios de venta en el vecindario de West Village por lo general superaron los US $ 2100 por pie cuadrado ($ 23 000 / m 2 ) en 2017. [11]

Geografía [ editar ]

Límites [ editar ]

El vecindario limita con Broadway al este, North River (parte del río Hudson ) al oeste, Houston Street al sur y 14th Street al norte. Se centra aproximadamente en Washington Square Park y la Universidad de Nueva York . Los vecindarios que lo rodean son East Village y NoHo al este, SoHo y Hudson Square al sur, y Chelsea y Union Square al norte. El East Village antes se consideraba parte del Lower East Sidey nunca se ha considerado parte de Greenwich Village. [12] La parte occidental de Greenwich Village se conoce como West Village ; la línea divisoria de su frontera oriental se debate pero comúnmente se cita como Séptima Avenida o Sexta Avenida . El Far West Village es otro subbarrio de Greenwich Village que limita al oeste con el río Hudson y al este con Hudson Street . [13]

A principios del siglo XX, Greenwich Village se distinguió del vecindario de clase alta de Washington Square, basado en el hito principal de Washington Square Park [14] [15] o Empire Ward [16] en el siglo XIX.

Enciclopedia Británica ' s artículo de 1956 en los estados 'Nueva York (Ciudad)'(bajo el subtítulo 'Greenwich Village') que la frontera sur de la Villa es Spring Street , lo que refleja una comprensión más temprano. Hoy, Spring Street se superpone con la designación de vecindario moderno y más nuevo SoHo, mientras que la moderna Encyclopædia Britannica cita la frontera sur como Houston Street. [17]

Plan de cuadrícula [ editar ]

Como Greenwich Village fue una vez a la rural, aislada aldea al norte de la colonización europea del siglo 17 en la isla de Manhattan , el trazado de las calles es más orgánico que el patrón de rejilla prevista del siglo 19 plan de la red (basado en las Plan de los Comisarios de 1811 ) . A Greenwich Village se le permitió mantener el patrón de calles del siglo XVIII de lo que ahora se llama West Village: áreas que ya estaban construidas cuando se implementó el plan, al oeste de lo que ahora es Greenwich Avenue y Sixth Avenue , dieron como resultado un vecindario cuyas calles son dramáticamente diferente, en diseño, de la estructura ordenada de las partes más nuevas de Manhattan. [18]

Muchas de las calles del vecindario son estrechas y algunas se curvan en ángulos extraños. En general, se considera que esto se suma tanto al carácter histórico como al encanto del vecindario. Además, como la serpenteante Greenwich Street solía estar en la costa del río Hudson , gran parte del vecindario al oeste de Greenwich Street está en un vertedero, pero aún sigue la cuadrícula de calles más antigua. [18] Cuando se construyeron las Avenidas Sexta y Séptima a principios del siglo XX, se construyeron en diagonal al plano de la calle existente, y muchas calles más antiguas y más pequeñas tuvieron que ser demolidas. [18]

A diferencia de las calles de la mayor parte de Manhattan por encima de la calle Houston, las calles del Village suelen tener nombre en lugar de numerarse. Si bien algunas de las calles anteriormente nombradas (incluidas las calles Factory, Herring y Amity) ahora están numeradas, todavía no siempre se ajustan al patrón de cuadrícula habitual cuando ingresan al vecindario. [18] Por ejemplo, West 4th Street corre de este a oeste a través de la mayor parte de Manhattan, pero corre de norte a sur en Greenwich Village, lo que hace que se cruce con las calles West 10th, 11th y 12th antes de terminar en West 13th Street. [18]

Una gran sección de Greenwich Village, compuesta por más de 50 cuadras norte y oeste en el área hasta la calle 14, es parte de un Distrito Histórico establecido por la Comisión de Preservación de Monumentos Históricos de la Ciudad de Nueva York . Las intrincadas fronteras del Distrito no se extienden más al sur que 4th Street o St. Luke's Place, y no más al este que Washington Square East o University Place. [19] La remodelación en esa área está severamente restringida y los desarrolladores deben preservar la fachada principal y la estética de los edificios durante la renovación.

La mayoría de los edificios de Greenwich Village son apartamentos de media altura, casas adosadas del siglo XIX y, ocasionalmente, una sola familia sin ascensor, un marcado contraste con el paisaje de gran altura en Midtown y el centro de Manhattan .

Representación política [ editar ]

Políticamente, Greenwich Village se encuentra en el décimo distrito del Congreso de Nueva York . [20] [21] También se encuentra en el Senado del Estado de Nueva York 'distrito 25 s, [22] [23] de la Asamblea del Estado de Nueva York ' del distrito 66º s, [24] [25] y el Consejo de la Ciudad de Nueva York s' 3er distrito. [26]

Historia [ editar ]

Primeros años [ editar ]

En el siglo XVI, los nativos americanos se referían a su esquina noroeste más lejana, junto a la ensenada del río Hudson en la actual calle Gansevoort, como Sapokanikan ("campo de tabaco"). La tierra fue limpiada y convertida en pastos por los colonos holandeses y africanos liberados en la década de 1630, quienes llamaron a su asentamiento Noortwyck (también deletreado Noortw ij ck , "distrito del norte", equivalente a 'North wich / Northwick'). En la década de 1630, el gobernador Wouter van Twiller cultivaba tabaco en 200 acres (0,81 km 2 ) aquí en su "Granja en el bosque". [27] Los ingleses conquistaron el asentamiento holandés de Nueva Holanda.en 1664, y Greenwich Village se desarrolló como una aldea separada de la ciudad más grande de Nueva York hacia el sur en un terreno que eventualmente se convertiría en el Distrito Financiero . En 1644, los once colonos africanos holandeses fueron liberados después de la primera protesta legal negra en América. [b] Todos recibieron parcelas de tierra en lo que ahora es Greenwich Village, [28] en un área que se conoció como la Tierra de los Negros .

La primera referencia conocida al nombre de la aldea como "Greenwich" se remonta a 1696, en el testamento de Yellis Mandeville de Greenwich; sin embargo, la aldea no se mencionó en los registros de la ciudad hasta 1713. [29] Sir Peter Warren comenzó a acumular tierras en 1731 y construyó una casa de madera lo suficientemente espaciosa para albergar una sesión de la Asamblea cuando la viruela hizo que la ciudad fuera peligrosa en 1739. Su casa , que sobrevivió hasta la época de la Guerra Civil , dominaba el North River desde un acantilado; su sitio en la cuadra delimitada por las calles Perry y Charles, las calles Bleecker y West 4th, [30] todavía se puede reconocer por sus casas en hileras de mediados del siglo XIX insertadas en un vecindario que aún conserva muchas casas del boom de 1830-1837.

Desde 1797 [31] hasta 1829, [32] el bucólico pueblo de Greenwich fue la ubicación de la primera penitenciaría del estado de Nueva York , la prisión de Newgate, en el río Hudson en lo que ahora es West 10th Street , [31] cerca del muelle de Christopher Street . [33] El edificio fue diseñado por Joseph-François Mangin , quien luego codiseñaría el Ayuntamiento de Nueva York . [34] Aunque la intención de su primer alcaide, el reformador de prisiones cuáquero Thomas Eddy, debía proporcionar un lugar racional y humanitario para la retribución y la rehabilitación, la prisión pronto se convirtió en un lugar hacinado y pestilente, sujeto a frecuentes disturbios por parte de los presos que dañaron los edificios y mataron a algunos reclusos. [31] En 1821, la prisión, diseñada para 432 reclusos, tenía en su lugar 817, un número que solo fue posible gracias a la frecuente liberación de prisioneros, a veces hasta 50 por día. [35] Dado que la prisión estaba al norte de los límites de la ciudad de Nueva York en ese momento, ser sentenciado a Newgate se conoció como "enviado río arriba". Este término se popularizó una vez que los prisioneros comenzaron a ser condenados a la prisión de Sing Sing , en la ciudad de Ossining, río arriba de la ciudad de Nueva York. [33]

La casa más antigua que queda en Greenwich Village es la Casa Isaacs-Hendricks, en 77 Bedford Street (construida en 1799, muy modificada y ampliada en 1836, tercer piso en 1928). [36] Cuando se fundó la Iglesia de San Lucas en los Campos en 1820, se encontraba en los campos al sur de la carretera (ahora Christopher Street) que conducía desde Greenwich Lane (ahora Greenwich Avenue ) hasta un rellano en el North River. En 1822, una epidemia de fiebre amarilla en Nueva York alentó a los residentes a huir al aire más saludable de Greenwich Village, y luego muchos se quedaron. El futuro sitio de Washington Square era un campo de alfarerosde 1797 a 1823, cuando hasta 20.000 de los pobres de Nueva York fueron enterrados aquí, y aún permanecen. Las hermosas casas en hilera del renacimiento griego en el lado norte de Washington Square se construyeron alrededor de 1832, estableciendo la moda de Washington Square y la Quinta Avenida en las próximas décadas. Hasta bien entrado el siglo XIX, el distrito de Washington Square se consideraba separado de Greenwich Village.

Reputación como bohemia urbana [ editar ]

Greenwich Village fue históricamente conocido como un hito importante en el mapa de la cultura bohemia estadounidense a principios y mediados del siglo XX. El barrio era conocido por sus residentes artísticos y coloridos y la cultura alternativa que propagaban. Debido en parte a las actitudes progresistas de muchos de sus residentes, la Villa fue un punto focal de nuevos movimientos e ideas, ya sean políticas, artísticas o culturales. Esta tradición como enclave de cultura alternativa y de vanguardia se estableció durante el siglo XIX y continuó hasta el siglo XX, cuando prosperaron las pequeñas imprentas, las galerías de arte y el teatro experimental. En 1969, miembros enfurecidos de la comunidad gay, en busca de igualdad, comenzaron los disturbios de Stonewall . LaStonewall Inn fue posteriormente reconocido como Monumento Histórico Nacional por haber sido el lugar donde se originó el movimiento por los derechos de los homosexuales. [37] [38] [39]

El edificio del estudio de la calle Tenth estaba situado en 51 West 10th Street entre las avenidas Quinta y Sexta. El edificio fue encargado por James Boorman Johnston [c] y diseñado por Richard Morris Hunt . Su diseño innovador pronto representó un prototipo arquitectónico nacional, y contó con una galería central abovedada, desde la cual irradiaban habitaciones interconectadas. El estudio de Hunt dentro del edificio albergó la primera escuela de arquitectura en los Estados Unidos. Poco después de su finalización en 1857, el edificio ayudó a hacer de Greenwich Village el centro de las artes en la ciudad de Nueva York, atrayendo a artistas de todo el país para trabajar, exhibir y vender su arte. En sus primeros años, Winslow Homer tomó un estudio allí, [41] al igual queEdward Lamson Henry y muchos de los artistas de la Escuela del Río Hudson , incluidos Frederic Church y Albert Bierstadt . [42]

Desde finales del siglo XIX hasta la actualidad, el Hotel Albert ha sido un icono cultural de Greenwich Village. Inaugurado durante la década de 1880 y originalmente ubicado en 11th Street y University Place, llamado Hotel St. Stephan y luego, después de 1902, llamado Hotel Albert mientras estaba bajo la propiedad de William Ryder, sirvió como lugar de reunión, restaurante y vivienda para varios importantes artistas y escritores desde finales del siglo XIX hasta bien entrado el siglo XX. Después de 1902, el hermano del propietario, Albert Pinkham Ryder, vivió y pintó allí. Algunos otros invitados destacados que vivieron allí incluyen: Augustus St. Gaudens , Robert Louis Stevenson , Mark Twain , Hart Crane , Walt Whitman, Anaïs Nin , Thomas Wolfe , Robert Lowell , Horton Foote , Salvador Dalí , Philip Guston , Jackson Pollock y Andy Warhol . [43] [44] Durante la época dorada de la bohemia , Greenwich Village se hizo famoso por excéntricos como Joe Gould (descrito en detalle por Joseph Mitchell ) y Maxwell Bodenheim , la bailarina Isadora Duncan , el escritor William Faulkner y el dramaturgo Eugene O'Neill. La rebelión política también hizo su hogar aquí, ya sea seria ( John Reed ) o frívola ( Marcel Duchamp y sus amigos lanzaron globos desde lo alto de Washington Square Arch , proclamando la fundación de "La República Independiente de Greenwich Village" el 24 de enero de 1917). [45] [46]

En 1924, se estableció el Cherry Lane Theatre . Ubicado en 38 Commerce Street, es el teatro Off-Broadway más antiguo de Nueva York que funciona continuamente . Un hito en el paisaje cultural de Greenwich Village, fue construido como un silo agrícola en 1817, y también sirvió como almacén de tabaco y fábrica de cajas antes de que Edna St. Vincent Millay y otros miembros de Provincetown Players convirtieran la estructura en un teatro al que bautizaron como el Cherry Lane Playhouse, que se inauguró el 24 de marzo de 1924 con la obra The Man Who Ate the Popomack . Durante la década de 1940 The Living Theatre , Theatre of the Absurd, y el movimiento Downtown Theatre se arraigó allí, y se ganó la reputación de ser un escaparate para los aspirantes a dramaturgos y las voces emergentes.

En una de las muchas propiedades de Manhattan que poseían Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney y su esposo, Gertrude Whitney estableció el Whitney Studio Club en 8 West 8th Street en 1914, como una instalación donde los jóvenes artistas podían exhibir sus obras. En la década de 1930, se había convertido en su mayor legado, el Whitney Museum of American Art , en el sitio de la actual New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture . El Whitney fue fundado en 1931, como respuesta al Museo de Arte Moderno , fundado en 1928, y su colección de modernismo mayoritariamente europeo y su abandono del arte estadounidense.. Gertrude Whitney decidió invertir tiempo y dinero en el museo después de que el Museo Metropolitano de Arte de Nueva York rechazara su oferta de contribuir con su colección de veinticinco años de obras de arte moderno . [47] En 1936, el renombrado artista y profesor expresionista abstracto Hans Hofmann trasladó su escuela de arte de East 57th Street a 52 West 9th Street. En 1938, Hofmann se mudó nuevamente a una casa más permanente en 52 West 8th Street. La escuela permaneció activa hasta 1958, cuando Hofmann se retiró de la docencia. [48]

El 8 de enero de 1947, el estibador Andy Hintz fue asesinado a tiros por los sicarios John M. Dunn , Andrew Sheridan y Danny Gentile frente a su apartamento. Antes de morir el 29 de enero, le dijo a su esposa que "Johnny Dunn me disparó". [49] Los tres hombres armados fueron arrestados inmediatamente. Sheridan y Dunn fueron ejecutados. [50]

El pueblo fue sede de la primera nación racialmente integrado discoteca , [51] cuando el Café Society fue abierto en 1938 en 1 Sheridan Square [52] por Barney Josephson . Café Society exhibió talento afroamericano y estaba destinado a ser una versión estadounidense de los cabarets políticos que Josephson había visto en Europa antes de la Primera Guerra Mundial . Artistas notables allí incluyeron: Pearl Bailey , Count Basie , Nat King Cole , John Coltrane , Miles Davis , Ella Fitzgerald , Coleman Hawkins, Billie Holiday , Lena Horne , Burl Ives , Lead Belly , Anita O'Day , Charlie Parker , Les Paul y Mary Ford , Paul Robeson , Kay Starr , Art Tatum , Sarah Vaughan , Dinah Washington , Josh White , Teddy Wilson , Lester Young y los Weavers , quienes también en la Navidad de 1949 tocaron en el Village Vanguard .

El desfile anual de Halloween de Greenwich Village , iniciado en 1974 por el titiritero y fabricante de máscaras de Greenwich Village Ralph Lee , es el desfile de Halloween más grande del mundo y el único desfile nocturno importante de Estados Unidos, que atrae a más de 60.000 participantes disfrazados , dos millones de espectadores en persona y un audiencia televisiva de más de 100 millones. [53]

Posguerra [ editar ]

Greenwich Village volvió a ser importante para la escena bohemia durante la década de 1950, cuando la Generación Beat centró sus energías allí. Huyendo de lo que veían como una conformidad social opresiva, una colección dispersa de escritores, poetas, artistas y estudiantes (más tarde conocidos como los Beats ) y los Beatniks , se mudaron a Greenwich Village y a North Beach en San Francisco , creando de muchas maneras los predecesores de la costa este y oeste de EE. UU. , respectivamente, a la escena hippie de East Village - Haight Ashbury de la próxima década. The Village (y los alrededores de la ciudad de Nueva York) más tarde desempeñaría un papel central en los escritos de, entre otros, Maya Angelou , James Baldwin , William S. Burroughs , Truman Capote , Allen Ginsberg , Jack Kerouac , Rod McKuen , Marianne Moore y Dylan. Thomas , quien se derrumbó en el Hotel Chelsea y murió en el Hospital St. Vincents en 170 West 12th Street, en el Village después de beber en White Horse Tavern el 5 de noviembre de 1953.

Off-Off-Broadway began in Greenwich Village in 1958 as a reaction to Off Broadway, and a "complete rejection of commercial theatre".[54] Among the first venues for what would soon be called "Off-Off-Broadway" (a term supposedly coined by critic Jerry Tallmer of the Village Voice) were coffeehouses in Greenwich Village, in particular, the Caffe Cino at 31 Cornelia Street, operated by the eccentric Joe Cino, who early on took a liking to actors and playwrights and agreed to let them stage plays there without bothering to read the plays first, or to even find out much about the content. Also integral to the rise of Off-Off-Broadway were Ellen Stewart at La MaMa, originally located at 321 E. 9th Street, and Al Carmines at the Judson Poets' Theater, located at Judson Memorial Church on the south side of Washington Square Park.

The Village had a cutting-edge cabaret and music scene. The Village Gate, the Village Vanguard, and the Blue Note (since 1981) regularly hosted some of the biggest names in jazz. Greenwich Village also played a major role in the development of the folk music scene of the 1960s. Music clubs included Gerde's Folk City, The Bitter End, Cafe Au Go Go, Cafe Wha?, The Gaslight Cafe and The Bottom Line. Three of the four members of the Mamas & the Papas met there. Guitarist and folk singer Dave Van Ronk lived there for many years. Village resident and cultural icon Bob Dylan by the mid-60s had become one of the world's foremost popular songwriters, and often developments in Greenwich Village would influence the simultaneously occurring folk rock movement in San Francisco and elsewhere, and vice versa. Dozens of other cultural and popular icons got their start in the Village's nightclub, theater, and coffeehouse scene during the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s, including Eric Andersen, Joan Baez, Jackson Browne, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, Richie Havens, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Ian, the Kingston Trio, the Lovin' Spoonful, Bette Midler, Liza Minnelli, Joni Mitchell, Maria Muldaur, Laura Nyro, Phil Ochs, Tom Paxton, Peter, Paul, and Mary, Carly Simon, Simon & Garfunkel, Nina Simone, Barbra Streisand, James Taylor, and the Velvet Underground. The Greenwich Village of the 1950s and 1960s was at the center of Jane Jacobs's book The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which defended it and similar communities, while criticizing common urban renewal policies of the time.

Founded by New York-based artist Mercedes Matter and her students, the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture is an art school formed in the mid-1960s in the Village. Officially opened September 23, 1964, the school is still active, at 8 W. 8th Street, the site of the original Whitney Museum of American Art.[55]

Greenwich Village was home to a safe house used by the radical anti-war movement known as the Weather Underground. On March 6, 1970, their safehouse was destroyed when an explosive device they were constructing was accidentally detonated, killing three of their members (Ted Gold, Terry Robbins, and Diana Oughton).

The Village has been a center for movements that challenged the wider American culture, for example, its role in the gay liberation movement. The Stonewall riots were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations by members of the gay community against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, 53 Christopher Street. Considered together, the demonstrations are widely considered to constitute the single most important event leading to the gay liberation movement and the modern fight for LGBT rights in the United States.[56][57] On June 23, 2015, the Stonewall Inn was the first landmark in New York City to be recognized by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission on the basis of its status in LGBT history,[58] and on June 24, 2016, the Stonewall National Monument was named the first U.S. National Monument dedicated to the LGBTQ-rights movement.[59] Greenwich Village contains the world's oldest gay and lesbian bookstore, Oscar Wilde Bookshop, founded in 1967, while The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center – best known as simply "The Center" – has occupied the former Food & Maritime Trades High School at 208 West 13th Street since 1984. In 2006, the Village was the scene of an assault involving seven lesbians and a straight man that sparked appreciable media attention, with strong statements defending both sides of the case.

Preservation[edit]

Since the end of the twentieth century, many artists and local historians have mourned the fact that the bohemian days of Greenwich Village are long gone, because of the extraordinarily high housing costs in the neighborhood.[60] The artists fled to other New York City neighborhoods including SoHo, Tribeca, Dumbo, Williamsburg, and Long Island City. Nevertheless, residents of Greenwich Village still possess a strong community identity and are proud of their neighborhood's unique history and fame, and its well-known liberal live-and-let-live attitudes.[60]

Historically, local residents and preservation groups have been concerned about development in the Village and have fought to preserve its architectural and historic integrity. In the 1960s, Margot Gayle led a group of citizens to preserve the Jefferson Market Courthouse (later reused as Jefferson Market Library),[61] while other citizen groups fought to keep traffic out of Washington Square Park,[62] and Jane Jacobs, using the Village as an example of a vibrant urban community, advocated to keep it that way.

Since then, preservation has been a part of the Village ethos. Shortly after the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) was established in 1965, it acted to protect parts of Greenwich Village, designating the small Charlton-King-Vandam Historic District in 1966, which contains the city's largest concentration of row houses in the Federal style, as well as a significant concentration of Greek Revival houses, and the even smaller MacDougal-Sullivan Gardens Historic District in 1967, a group of 22 houses sharing a common back garden, built in the Greek Revival style and later renovated with Colonial Revival façades. In 1969, the LPC designated the Greenwich Village Historic District – which remained the city's largest for four decades – despite preservationists' advocacy for the entire neighborhood to be designated an historic district. Advocates continued to pursue their goal of additional designation, spurred in particular by the increased pace of development in the 1990s.

Rezoned areas[edit]

The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation (GVSHP), a nonprofit organization dedicated to the architectural and cultural character and heritage of the neighborhood, successfully proposed new districts and individual landmarks to the LPC. Those include:[63]

- Gansevoort Market Historic District was the first new historic district in Greenwich Village in 34 years. The 112 buildings on 11 blocks protect the city's distinctive Meatpacking District with its cobblestone streets, warehouses and rowhouses. About 70 percent of the area proposed by GVSHP in 2000 was designated a historic district by the LPC in 2003, while the entire area was listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places in 2007.[64][65]

- Weehawken Street Historic District, designated in 2006, is a 14-building, three-block district near the Hudson River centering on tiny Weehawken Street and containing an array of architecture including a sailors' hotel, former stables, and a wooden house.[66]

- Greenwich Village Historic District Extension I, designated in 2006, brought 46 more buildings on three blocks into the district, thus protecting warehouses, a former public school and police station, and early 19th century rowhouses. Both the Weehawken Street Historic District and the Greenwich Village Historic District Extension I were designated by the LPC in response to the larger proposal for a Far West Village Historic District submitted by GVSHP in 2004.[66]

- Greenwich Village Historic District Extension II, designated in 2010, embracing 225 buildings on 12 blocks, contains 19th century houses, 19th and 20th century tenements, and a variety of cultural landmarks.[67]

- South Village Historic District, designated in 2013, covers 235 buildings on 13 blocks, representing the largest single expansion of landmark protections in Greenwich Village since 1969. It includes well-preserved and renovated 19th century houses, colorful tenements, and a variety of sites important to the area's rich immigrant, artistic, and Italian-American history, as well as several low-rise, historically significant New York University buildings on Washington Square South.[68]

The Landmarks Preservation Commission designated as landmarks several individual sites proposed by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, including the former Bell Telephone Labs Complex (1861–1933), now Westbeth Artists' Housing, designated in 2011;[69] the Silver Towers/University Village Complex (1967), designed by I.M. Pei and including the Picasso sculpture "Portrait of Sylvette," designated in 2008;[70] and three early 19th-century federal houses at 127, 129 and 131 MacDougal Street.

Several contextual rezonings were enacted in Greenwich Village in recent years to limit the size and height of allowable new development in the neighborhood, and to encourage the preservation of existing buildings. The following were proposed by the GVSHP and passed by the City Planning Commission:

- Far West Village Rezoning, approved in 2005, was the first downzoning in Manhattan in many years, putting in place new height caps, thus ending construction of high-rise waterfront towers in much of the Village and encouraging the reuse of existing buildings.[71]

- Washington and Greenwich Street Rezoning, approved in 2010, was passed in near-record time to protect six blocks from out-of-scale hotel development and maintain the low-rise character.[72]

NYU dispute[edit]

New York University and Greenwich Village preservationists have been embroiled in a conflict over campus expansion versus preservation of the scale and Bohemian character of the Village.[73]

As one press critic put it in 2013, "For decades, New York University has waged architectural war on Greenwich Village."[74] Recent examples of the university clashing with the community, often led by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, include the destruction of the 85 West Third Street house where Edgar Allan Poe lived from 1844–5, which NYU promised to rebuild using original materials, but then claimed not to have enough bricks to do so; the construction of the 26-story Founders Hall dorm behind the façade of demolished St. Ann's Church at 120 East Twelfth Street, which advocates protested as being out of scale for the low-rise area, and received assurances from NYU, which then built all 26 stories anyway;[75] and the demolition in 2009 of the Provincetown Playhouse and Apartments, over protests.[76]

In 2008, as part of a multi-stakeholder Community Task Force on NYU Development, the university agreed to a set of "Planning Principles."[77] Yet advocates did not find NYU was following the principles in practice, culminating in a successful lawsuit against the university's "NYU 2031" plan for expansion.[78]

Demographics[edit]

For census purposes, the New York City government classifies Greenwich Village as part of the West Village neighborhood tabulation area.[79] Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of West Village was 66,880, a change of −1,603 (−2.4%) from the 68,483 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 583.47 acres (236.12 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 114.6 inhabitants per acre (73,300/sq mi; 28,300/km2).[80] The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 80.9% (54,100) White, 2% (1,353) African American, 0.1% (50) Native American, 8.2% (5,453) Asian, 0% (20) Pacific Islander, 0.4% (236) from other races, and 2.4% (1,614) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.1% (4,054) of the population.[81]

The entirety of Community District 2, which comprises Greenwich Village and SoHo, had 91,638 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 85.8 years.[82]:2, 20 This is higher than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[83]:53 (PDF p. 84)[84] Most inhabitants are adults: a plurality (42%) are between the ages of 25–44, while 24% are between 45–64, and 15% are 65 or older. The ratio of youth and college-aged residents was lower, at 9% and 10% respectively.[82]:2

As of 2017, the median household income in Community Districts 1 and 2 (including the Financial District and Tribeca) was $144,878,[85] though the median income in Greenwich Village individually was $119,728.[2] In 2018, an estimated 9% of Greenwich Village and SoHo residents lived in poverty, compared to 14% in all of Manhattan and 20% in all of New York City. One in twenty-five residents (4%) were unemployed, compared to 7% in Manhattan and 9% in New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 38% in Greenwich Village and SoHo, compared to the boroughwide and citywide rates of 45% and 51% respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018[update], Greenwich Village and SoHo are considered high-income relative to the rest of the city and not gentrifying.[82]:7

Points of interest[edit]

Greenwich Village includes several collegiate institutions. Since the 1830s, New York University (NYU) has had a campus there. In 1973 NYU moved from its campus in University Heights in the West Bronx (the current site of Bronx Community College), to Greenwich Village with many buildings around Gould Plaza on West 4th Street. In 1976 Yeshiva University established the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in the northern part of Greenwich Village. In the 1980s Hebrew Union College was built in Greenwich Village. The New School, with its Parsons The New School for Design, a division of The New School, and the School's Graduate School expanded in the 2000s, with the renovated, award-winning design of the Sheila C. Johnson Design Center at 66 Fifth Avenue on 13th Street. The Cooper Union is located in Greenwich Village, at Astor Place, near St. Mark's Place on the border of the East Village. Pratt Institute established its latest Manhattan campus in an adaptively reused Brunner & Tryon-designed loft building on 14th Street, east of Seventh Avenue. The university campus building expansion was followed by a gentrification process in the 1980s.

The historic Washington Square Park is the center and heart of the neighborhood. Additionally, the Village has several other, smaller parks: Christopher, Father Fagan, Little Red Square, Minetta Triangle, Petrosino Square, and Time Landscape. There are also city playgrounds, including DeSalvio Playground, Minetta, Thompson Street, Bleecker Street, Downing Street, Mercer Street, Cpl. John A. Seravelli, and William Passannante Ballfield. One of the most famous courts, is "The Cage", officially known as the West Fourth Street Courts. Sitting atop the We subway station at Sixth Avenue, the courts are used by basketball and American handball players from across the city. The Cage has become one of the most important tournament sites for the citywide "Streetball" amateur basketball tournament. Since 1975, New York University's art collection has been housed at the Grey Art Gallery bordering Washington Square Park, at 100 Washington Square East. The Grey Art Gallery is notable for its museum-quality exhibitions of contemporary art.

The Village has a bustling performing arts scene. It is home to many Off Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway theaters; for instance, Blue Man Group has taken up residence in the Astor Place Theater. The Village Gate (until 1992), the Village Vanguard and the Blue Note are still presenting some of the biggest names in jazz on a regular basis. Other music clubs include The Bitter End, and Lion's Den. The Village has its own orchestra aptly named the Greenwich Village Orchestra. Comedy clubs dot the Village as well, including Comedy Cellar, where many American stand-up comedians got their start.

Several publications have offices in the Village, most notably the monthly magazines American Heritage and Fortune and formerly also the citywide newsweekly the Village Voice. The National Audubon Society, having relocated its national headquarters from a mansion in Carnegie Hill to a restored and very green, former industrial building in NoHo, relocated to smaller but even greener LEED certified building at 225 Varick Street,[86] on Houston Street near the Film Forum.

Police and crime[edit]

Greenwich Village is patrolled by the 6th Precinct of the NYPD, located at 233 West 10th Street.[87] The 6th Precinct ranked 68th safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010. This is due to a high incidence of property crime.[88] As of 2018[update], with a non-fatal assault rate of 10 per 100,000 people, Greenwich Village's rate of violent crimes per capita is less than that of the city as a whole. The incarceration rate of 100 per 100,000 people is lower than that of the city as a whole.[82]:8

The 6th Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 80.6% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct reported 1 murder, 20 rapes, 153 robberies, 121 felony assaults, 163 burglaries, 1,031 grand larcenies, and 28 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[89]

Fire safety[edit]

Greenwich Village is served by two New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[90]

- Engine Company 24/Ladder Company 5/Battalion 2 – 227 6th Avenue[91]

- Squad 18 – 132 West 10th Street[92]

Health[edit]

As of 2018[update], preterm births are more common in Greenwich Village and SoHo than in other places citywide, though births to teenage mothers are less common. In Greenwich Village and SoHo, there were 91 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 1 teenage birth per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide), though the teenage birth rate is based on a small sample size.[82]:11 Greenwich Village and SoHo have a low population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 4%, less than the citywide rate of 12%, though this was based on a small sample size.[82]:14

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Greenwich Village and SoHo is 0.0095 milligrams per cubic metre (9.5×10−9 oz/cu ft), more than the city average.[82]:9 Sixteen percent of Greenwich Village and SoHo residents are smokers, which is more than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers.[82]:13 In Greenwich Village and SoHo, 4% of residents are obese, 3% are diabetic, and 15% have high blood pressure, the lowest rates in the city—compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively.[82]:16 In addition, 5% of children are obese, the lowest rate in the city, compared to the citywide average of 20%.[82]:12

Ninety-six percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is more than the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 91% of residents described their health as "good," "very good," or "excellent," more than the city's average of 78%.[82]:13 For every supermarket in Greenwich Village and SoHo, there are 7 bodegas.[82]:10

The nearest major hospitals are Beth Israel Medical Center in Stuyvesant Town, as well as the Bellevue Hospital Center and NYU Langone Medical Center in Kips Bay, and NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital in the Civic Center area.[93][94]

Post offices and ZIP Codes[edit]

Greenwich Village is located within four primary ZIP Codes. The subsection of West Village, south of Greenwich Avenue and west of Sixth Avenue, is located in 10014, while the northwestern section of Greenwich Village north of Greenwich Avenue and Washington Square Park and west of Fifth Avenue is in 10011. The northeastern part of the Village, north of Washington Square Park and east of Fifth Avenue, is in 10003. The neighborhood's southern portion, the area south of Washington Square Park and east of Sixth Avenue, is in 10012.[95] The United States Postal Service operates three post offices near Greenwich Village:

- Patchin Station – 70 West 10th Street[96]

- Village Station – 201 Varick Street[97]

- West Village Station – 527 Hudson Street[98]

Education[edit]

Greenwich Village and SoHo generally have a higher rate of college-educated residents than the rest of the city as of 2018[update]. The vast majority of residents age 25 and older (84%) have a college education or higher, while 4% have less than a high school education and 12% are high school graduates or have some college education. By contrast, 64% of Manhattan residents and 43% of city residents have a college education or higher.[82]:6 The percentage of Greenwich Village and SoHo students excelling in math rose from 61% in 2000 to 80% in 2011, and reading achievement increased from 66% to 68% during the same time period.[99]

Greenwich Village and SoHo's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is lower than the rest of New York City. In Greenwich Village and SoHo, 7% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, less than the citywide average of 20%.[83]:24 (PDF p. 55)[82]:6 Additionally, 91% of high school students in Greenwich Village and SoHo graduate on time, more than the citywide average of 75%.[82]:6

Schools[edit]

Greenwich Village residents are zoned to two elementary schools: PS 3, Melser Charrette School, and PS 41, Greenwich Village School. Residents are zoned to Baruch Middle School 104. Residents apply to various New York City high schools. The private Greenwich Village High School was formerly located in the area, but later moved to SoHo.[100][101][102]

Greenwich Village is home to New York University, which owns large sections of the area and most of the buildings around Washington Square Park.[7][8] To the north is the campus of The New School, which is housed in several buildings that are considered historical landmarks because of their innovative architecture.[103] The New School's Sheila Johnson Design Center doubles as a public art gallery.[104] Cooper Union has been located in the East Village since its founding in 1859.[105][106]

Libraries[edit]

The New York Public Library (NYPL) operates two branches in Greenwich Village. The Jefferson Market Library is located at 425 Avenue of the Americas (Sixth Avenue). The building was a courthouse in the 19th and 20th centuries before being converted into a library in 1967, and it is now a city designated landmark.[107] The Hudson Park branch is located at 66 Leroy Street. The branch is housed in Carnegie library that was built in 1906 and expanded in 1920.[108]

Transportation[edit]

Greenwich Village is served by the IND Eighth Avenue Line (A, C, and E trains), the IND Sixth Avenue Line (B, D, F, <F>, and M trains), the BMT Canarsie Line (L train), and the IRT Broadway–Seventh Avenue Line (1, 2, and 3 trains) of the New York City Subway. The 14th Street/Sixth Avenue, 14th Street/Eighth Avenue, West Fourth Street–Washington Square, and Christopher Street–Sheridan Square stations are in the neighborhood.[109] Local New York City Bus routes, operated by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, include the M55, M7, M11, M14, and M20.[110] On the PATH, the Christopher Street, Ninth Street, and 14th Street stations are in Greenwich Village.

Notable residents[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Greenwich Village has long been a popular neighborhood for numerous artists and other notable people. Past and present notable residents include:

- Edward Albee (1928–2016), playwright[111]

- Alec Baldwin (born 1958), actor[112][113]

- Richard Barone, musician, producer[114]

- Paul Bateson (born 1940), convicted murderer who was in The Exorcist[115]

- Brie Bella (born 1983), wrestler

- Nate Berkus (born 1971), interior designer[116]

- David Blue (1941-1982), folksinger, companion of Bob Dylan

- Matthew Broderick (born 1962), actor[113][117]

- Barbara Pierce Bush (born 1981), daughter of former U.S. President George W. Bush[118]

- Francesco Carrozzini (born 1982), film director and photographer[119]

- Jessica Chastain (born 1977), actress[113]

- Ramsey Clark lawyer and activist "West View NewsDate April 7, 2018 acceesdate:

- Francesco Clemente (born 1952) contemporary artist[119]

- Jacob Cohen (1923–1983), statistician and psychologist[120]

- Anderson Cooper (born 1967), CNN anchor[113][121]

- Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), English occultist.

- Hugh Dancy (born 1975), actor[122]

- Claire Danes (born 1979), actress[122]

- Robert De Niro (born 1943), actor[123]

- Brian De Palma (born 1940), screenwriter[113]

- Floyd Dell (1887–1969), novelist, playwright, poet and managing editor of The Masses[124]

- Leonardo DiCaprio (born 1974), actor[113]

- Robert Downey Jr. (born 1965), actor and singer[125]

- Steve Earle (born 1955), musician[126]

- Crystal Eastman (1881–1928), lawyer and leader in the fight for woman's suffrage[127]

- Maurice Evans (1901–1989), British actor noted for his interpretations of Shakespearean characters[111]

- Andrew Garfield (born 1983), actor [128][better source needed]

- Hank Greenberg (1911–1986), Hall of Fame baseball player[129]

- John P. Hammond (born 1942), blues singer and guitarist[119]

- Jerry Herman (1931-2019), composer and lyricist[130]

- Edward Hopper (1882–1967), painter[131]

- Marc Jacobs (born 1963), fashion designer[132]

- Max Kellerman (born 1973), sports commentator

- Eva Kotchever (1891-1943), owner of Eve's Hangout, also called Eve Adams’ Tearoom, situated at 129 MacDougal St, deported to Europe and died at Auschwitz.[133]

- Annie Leibovitz (born 1949), photographer[113]

- Arthur MacArthur IV (born 1938), musician, son of General Douglas MacArthur

- Bob Melvin (born 1961), Major League Baseball player and manager

- Edna St. Vincent Millay, poet and playwright[134]

- Julianne Moore (born 1960), actress[135]

- Nickolas Muray (born Miklós Mandl; 1892–1965), Hungarian-born American photographer and Olympic fencer[136]

- Bebe Neuwirth (born 1958), actress[137]

- Edward Norton (born 1969), actor and filmmaker[138]

- Rosie O'Donnell, actress and comedian[113]

- Mary-Kate Olsen, actress and fashion designer[113]

- Mary-Louise Parker, actress[113]

- Sarah Jessica Parker (born 1965), actress[113]

- Sean Parker (born 1979), entrepreneur[113]

- Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), poet and novelist[139]

- Leontyne Price (born 1927), soprano[140]

- Daniel Radcliffe (born 1989), actor[141]

- Gilda Radner (1946–1989), actress and comedian[113]

- Rachael Ray, television personality and cook[113]

- Julia Roberts (born 1967), actress[113]

- Susan Sarandon (born 1946), actress[113]

- John Sebastian (born 1944), musician[142]

- Amy Sedaris (born 1961), actress[143]

- James Spader, actor[144]

- Pat Steir (born 1938), painter and printmaker[119]

- Emma Stone (born 1988), actress[145]

- Uma Thurman (born 1970), actress[118][146]

- Tiny Tim (musician) (1932-1996), singer

- Marisa Tomei (born 1964), actress[147]

- Calvin Trillin (born 1935), feature writer for The New Yorker magazine.[148]

- Liv Tyler (born 1977), actress[149]

- Edgard Varèse (1883–1965), French-born composer [119]

- Anna Wintour (born 1949), editor-in-chief of Vogue magazine[119]

In popular culture[edit]

Comics[edit]

- In the DC Comics universe, Wonder Woman lived in the "Village" in New York City (never called by its full name, but clearly depicted as Greenwich Village) during the late 1960s and early 1970s, when she had lost most of her superpowers. Madame Xanadu lived on Chrystie Street, described alternately as being in "Greenwich Village" and the "East Village."

- In the Marvel Comics universe, Master of the Mystic Arts and Sorcerer Supreme, Doctor Strange, lives in a brownstone mansion in Greenwich Village. Doctor Strange's Sanctum Sanctorum is located at 177A Bleecker Street.

- In Akimi Yoshida's Banana Fish sequel/side story, Garden of Light, Eiji Okumura is stated to live in Greenwich Village as an accomplished photographer.

Film[edit]

- In Alfred Hitchcock's Rear Window (1954) James Stewart's character lives in a Greenwich Village apartment.[150]

- In Wonderful Town (1953), the Sherwood sisters leave 1935 Columbus, Ohio, for Greenwich Village to pursue their dreams of becoming a writer (Ruth) and an actress (Eileen). Their apartment was said to be on Christopher Street, though the actual apartment of author Ruth McKenney and her sister Eileen McKenney was at 14 Gay Street.

- In Funny Face (1957), Jo Stockton (Audrey Hepburn) works at a bookstore called Embryo Concepts in the Village, where she is discovered by Dick Avery (Fred Astaire).[151]

- In When Harry Met Sally..., Sally drops Harry off in front of the Washington Square Arch after they share a drive from University of Chicago.

- In Wait Until Dark (1967), Susy Hendrix (Audrey Hepburn) lives at 4 St. Luke's Place.[152]

- Next Stop, Greenwich Village (1976) chronicles the story of a young Jewish boy in 1953 who moves to the Village, looking to break into acting.

- The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984) centers on a maître d' (Mickey Rourke) in the Italian section of the Village.

- Big Daddy (1999), Adam Sandler and Cole/Dylan Sprouse's characters live in a Greenwich Village apartment.

- Chinese Coffee (2000), an independent film by Al Pacino, which features Pacino and Jerry Orbach, is set in Greenwich Village in 1982.

- The Collector of Bedford Street (2002) is a documentary set in Greenwich village. It is about the neighborhood block association on Bedford street setting up a trust fund for a mentally disabled man named Larry Selman.[153]

- In I Am Legend (2007) Will Smith's character lives in Washington Square.

- Greenwich Village is the setting for the restaurant 22 Bleecker in the Catherine Zeta-Jones, Aaron Eckhart and Abigail Breslin movie No Reservations (2007).

- In Wanderlust (2012) the characters played by Paul Rudd and Jennifer Aniston live in a New York City apartment located in the West Village.

- The Coen brothers' Inside Llewyn Davis (2013) depicts the Village in the early 1960s, focusing on the emerging folk scene.[154]

- In Avengers: Infinity War, a battle between the Avengers and the Black Order takes place in the Village.

Games[edit]

- Alex's stage in Street Fighter III: 2nd Impact takes place in Greenwich Village.

- Greenwich Village is a playable multiplayer map in the Freedom Fighters (2003) video game.

Literature[edit]

- In her non-fiction, Jane Jacobs frequently cites Greenwich Village as an example of a vibrant urban community, most notably in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities.[155]

- Frank and April Wheeler of the novel Revolutionary Road, and the film of the same name, used to share an apartment on Bethune Street in the West Village prior to the events of the story.[156]

- O. Henry's short story, "The Last Leaf", is set in Greenwich Village.

- The anti-hero of the book Mother Night by author Kurt Vonnegut, and the film of the same name, Howard W. Campbell Jr., resides in Greenwich Village after World War II and prior to his arrest by the Israelis.[157]

- In Lesley M. M. Blume's children's novel, Cornelia and the Audacious Escapades of the Somerset Sisters, the main characters reside in Greenwich Village.[158]

- The suggestion of moving to the Village shocks newlywed New York aristocrat Jamie "Rick" Ricklehouse in Nora Johnson's 1985 novel Tender Offer. The implication is telling of the Village's reputation in the New York of the 1960s before mass gentrification when it was perceived as lowly and beneath upper class society.[159]

Music[edit]

- The cover photo for The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan (1963) of Dylan and his then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo was taken on Jones Street near West 4th Street in Greenwich Village, near their apartment.[160]

- In an interview with Jann Wenner, John Lennon said, "I should have been born in New York, I should have been born in the Village, that's where I belong."[161]

- Buddy Holly and his wife Maria Elena Santiago lived in Apartment 4H of the Brevoort Apartments, at 11 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. Here he recorded the series of acoustic songs, including "Crying, Waiting, Hoping" and "What to Do," known as the "Apartment Tapes," which were released after his death.[162]

Television[edit]

- The ABC sitcom Barney Miller (1975–82) was set at the fictional 12th precinct NYPD station in Greenwich Village.

- The CBS sitcom Kate & Allie (1984–1989) was set in Greenwich Village.[163]

- The NBC sitcom Friends (1994–2004) is set in the Village. Central Perk was supposedly on Mercer or Houston Street, down the block from the Angelika Film Center;[d] and Phoebe lived at 5 Morton Street.[e] The building in the exterior shot of Chandler, Joey, Rachel, and Monica's apartment building is at the corner of Grove and Bedford Streets in the West Village.[164] One of the show's working titles was Once Upon a Time in the West Village. However, the address on Rachel's wedding invitation is 495 Grove Street, which is actually in Brooklyn.

- The Village features prominently throughout the six seasons of Mad Men. In Season 1, Don Draper is having an affair with artist Midge Daniels, who lives in the Village. In Season 4, Don moves to an apartment on Waverly Place and Sixth Avenue (specified, for example, in "Public Relations"). And in Season 6, Betty Francis goes to Greenwich Village looking for a family friend, in "The Doorway", and Joan Harris and her girlfriend Kate go on a night on the town that culminates at the Electric Circus, in "To Have and to Hold".[165][166]

- On Sex and the City (1998–2004), exterior shots of Carrie Bradshaw's apartment building are of 66 Perry Street, even though her address is given as on the Upper East Side.[citation needed]

- The NBC Sitcom The Cosby Show (1984–92) made several references to the Village during its run, and the townhouse used for exterior shots, though purportedly set in Brooklyn for purposes of the show, is actually located at 10 St. Luke's Place.[167]

- Mad About You was set in the Village. The Buchman's apartment building was at 5th Avenue & 12th Street, just a few blocks north of Washington Square Park.

- The Real World: Back to New York, the 2001 season of the MTV reality television series The Real World, was filmed in the Village.[168]

- Village Barn (1948–50), the first country music show on network television (NBC) originated from a nightclub of the same name in the basement of 52 West 8th Street.

- Greenwich Village is the setting for Disney's Wizards of Waverly Place and Girl Meets World.

Theater[edit]

- The play Bell, Book and Candle is partly set in Greenwich Village.

See also[edit]

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan below 14th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

- Cedar Tavern

- Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation

- The Church of the Ascension

- Village Care of New York

- Village People

- The Market NYC

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ During the period of Dutch control over the area, the Village was called Noortwyck ("Northern District", because of its location north of the original settlement on Manhattan Island). (The Dutch colony was seized by Great Britain in 1664.) Dutch colonist Yellis Mandeville, who moved to the Village in the 1670s, called it Groenwijck after the settlement on Long Island, where he previously lived.[6]

- ^ The eleven freed Blacks were Paul d'Angola, Big Manuel, Little Manuel, Manuel de Gerrit de Rens, Simon Congo, Anthony Portuguese. Gracia, Peter Santome, John Francisco, Little Anthony and John Fort Orange.[28]

- ^ James Boorman Johnston (1822–1887) was a son of the prominent Scottish-born New York merchant John Johnston, in partnership with James Boorman (1783–1866) as Boorman & Johnston, developers of Washington Square North, and a founder of New York University; a group portrait of the Johnston Children 1831, is at the Museum of the City of New York[40]

- ^ The Angelika Film Center was said to be "up the block" from Central Perk in "The One Where Ross Hugs Rachel", the sixth season's second episode, placing the coffee house on Mercer Street or Houston.

- ^ This address was given "The One With Joey's New Brain", episode 7–15.

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b "NYC Planning | Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Greenwich Village neighborhood in New York". Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Definition of Greenwich Village". Yahoo! Education. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011.

- ^ "NYPL Map Division, Greenwich Village". Nyplmaps.tumblr.com. January 25, 2014. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Greenwich Village". nnp.org. Archived from the original on March 17, 2007. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ a b "Campus Map". New York University. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ a b "New York Campus". New York University. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Strenberg, Adam (November 12, 2007). "Embers of Gentrification". New York Magazine. p. 5.

- ^ Erin Carlyle (October 8, 2014). "New York Dominates 2014 List of America's Most Expensive ZIP Codes". Forbes. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ West Village Housing, "trulia.com" Accessed January 13, 2016.

- ^ F.Y.I., "When did the East Village become the East Village and stop being part of the Lower East Side?", Jesse McKinley, The New York Times, June 1, 1995. Retrieved August 26, 2008.

- ^ McFarland, Gerald W. (2005). Inside Greenwich Village: A New York City Neighborhood, 1898-1918. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-502-9.

- ^ "Village History". The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ Gold 1988, p. 6

- ^ Harris, Luther S. (2003). Around Washington Square: An Illustrated History of Greenwich Village. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-7341-6.

- ^ "neighbourhood, New York City, New York, United States". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Walsh, Kevin (November 1999). "The Street Necrology of Greenwich Village". Forgotten NY. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ "Landmark Maps: Historic District Maps: Manhattan". Nyc.gov. Archived from the original on September 9, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ Congressional District 10, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ New York City Congressional Districts, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ Senate District 25, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ 2012 Senate District Maps: New York City, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed November 17, 2018.

- ^ Assembly District 66, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ 2012 Assembly District Maps: New York City, New York State Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment. Accessed November 17, 2018.

- ^ Current City Council Districts for New York County, New York City. Accessed May 5, 2017.

- ^ Gold 1988, p. 2

- ^ a b Asbury, Edith Evans (December 7, 1977). "Freed Black Farmers Tilled Manhattan's Soil in the 1600s". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- ^ Stokes, I.N. Phelps (1915–1928). The iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909 (v. 6). New York, NY: Robert H. Dodd. p. 159. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ^ Gold 1988, p. 3

- ^ a b c Burrows & Wallace 1999, pp. 366–367

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 448

- ^ a b Nevius, Michelle & Nevius, James (2009), Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, New York: Free Press, ISBN 141658997X, p. 53

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, p. 369

- ^ Burrows & Wallace 1999, pp. 505–506

- ^ Walsh, Kevin (2006). Forgotten New York: The Ultimate Urban Explorer's Guide to All Five Boroughs. p. 155.

- ^ a b Julia Goicichea (August 16, 2017). "Why New York City Is a Major Destination for LGBT Travelers". The Culture Trip. Retrieved February 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ "Johnston Children: John Taylor Johnston (1820–1893), James Boorman Johnston (1822–1887), Margaret Taylor Johnston (1825–1875), and Emily Proudfoot Johnston (1827–1831), (painting)". SIRIS.

- ^ "Evoking the World of Winslow Homer". The New York Times. August 17, 1997. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "History of the Tenth Street Studio". Tfaoi.com. November 16, 1997. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Hotel Albert history". Thehotelalbert.com. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ Gray, Christopher. "The Albert Hotel Addresses Its Myths", The New York Times, April 15, 2011. Accessed June 21, 2016.

- ^ "The Daily Plant, The Free And Independent Republic Of Washington Square". Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "The Arch Conspirators: A Centennial Celebration". Atlas Obscura.

- ^ Berman, Avis (1990). Rebels on Eighth Street: Juliana Force and the Whitney Museum of American Art. New York: Atheneum.

- ^ "Hans Hofmann Estate, retrieved December 19, 2008". Hanshofmann.org. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ "National Affairs: A Date at The Dance Hall". Time.com. March 7, 1949. p. 1.

- ^ "National Affairs: A Date at The Dance Hall". Time.com. March 7, 1949. p. 2.

- ^ William Robert Taylor, Inventing Times Square: commerce and culture at the crossroads of the world (1991), p. 176

- ^ Many sources give the address at 2 Sheridan Square: "Barney Josephson, Owner of Cafe Society Jazz Club, Is Dead at 86", The New York Times; see history of "The theater at One Sheridan Square" Archived October 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Village Halloween Parade. "History of the Parade". Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Viagas (2004, p. 72)

- ^ Matter, Mercedes (2002). "New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture: The School: Its History". nyss.org. New York Studio School. Archived from the original on April 26, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2016.

- ^ National Park Service (2008). "Workforce Diversity: The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". US Dept. of Interior. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "Obama inaugural speech references Stonewall gay-rights riots". North Jersey Media Group. January 21, 2013. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ "NYC grants landmark status to gay rights movement building". North Jersey Media Group. Associated Press. June 23, 2015. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ a b

- Roberts, Rex (July 29, 2002). "When Greenwich Village was a Bohemian paradise". Insight on the News. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Harris, Paul (August 14, 2005). "New York's heart loses its beat". Arts. London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- Kugelmass, Jack (November 1993). ""The Fun Is in Dressing up": The Greenwich Village Halloween Parade and the Reimagining of Urban Space". Social Text. 36 (36): 138–152. doi:10.2307/466393. JSTOR 466393.

- Lydersen, Kari (March 15, 1999). "SHAME OF THE CITIES: Gentrification in the New Urban America". LiP Magazine. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- Desloovere, Hesper (November 15, 2007). "City Living: Greenwich Village". New York City. Newsday. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- Fieldsteel, Patricia (October 19, 2005). "Remembering a time when the Village was affordable". The Villager. New York: Community Media LLC. 75 (22). Archived from the original on December 22, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- ^ "Margot Gayle, Urban Preservationist and Crusader With Style, Dies at 100". The New York Times. September 30, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ^ NYC Dept. of Parks and Recreation. "Shirley Hayes and the Preservation of Washington Square Park".

- ^ The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. "Preservation". Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ The New York Times (September 11, 2003). "Blood on the Street, and it's Chic". Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ The Villager. "Gansevoort Historic District Gets Final Approval From City". Archived from the original on September 2, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ a b The Observer. "Village Historic District Extension". Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Panel Enlarges Landmark Zone and Cites 2 Bronx Sites". The New York Times. June 22, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ The Villager. "Positively South Village: LPC Votes to Expand Historic District". Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ The Villager. "City Dubs Westbeth a Landmark". Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Pei's University Village Tops List of 7 Landmarks". The New York Times. November 18, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "City, Landmarks Looking to Rezone Part of West Village". Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ "Council Approves 2 Village Rezonings". crainsnewyork.com. Retrieved March 4, 2014.

- ^ Eli Rosenberg (March 19, 2014). "After A Long War, Can NYU and the Village Ever Make Peace?". Vox Media Inc. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Russell, James (December 11, 2013). "NYU Blights Village With Dumpsters, Fencing, Concrete". Bloomberg. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ Anderson, Lincoln (August 2, 2006). "Conceding nothing, NYU starts building megadorm". The Villager. 76 (11). Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ "Neighbors and Preservationists Protest..." www.gvshp.org. GVSHP. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ Arenson, Karen (January 30, 2008). "NYU Offers An Accord on Growth". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ Bagli, Charles (January 7, 2014). "Judge Blocks Part of NYU's Plan for Four Towers in Greenwich Village". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre – New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division – New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin – New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010, Population Division – New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Greenwich Village and Soho (Including Greenwich Village, Hudson Square, Little Italy, Noho, Soho, South Village and West Village)" (PDF). nyc.gov. NYC Health. 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "2016-2018 Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan: Take Care New York 2020" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ "New Yorkers are living longer, happier and healthier lives". New York Post. June 4, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "NYC-Manhattan Community District 1 & 2--Battery Park City, Greenwich Village & Soho PUMA, NY". Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ Wilson, Claire (April 6, 2008). "Audubon's New Home Brings the Outdoors In". The New York Times.

- ^ "NYPD – 6th Precinct". www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

- ^ "Greenwich Village – DNAinfo.com Crime and Safety Report". www.dnainfo.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "6th Precinct CompStat Report" (PDF). www.nyc.gov. New York City Police Department. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "FDNY Firehouse Listing – Location of Firehouses and companies". NYC Open Data; Socrata. New York City Fire Department. September 10, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Engine Company 24/Ladder Company 5/Battalion 2". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Squad 18". FDNYtrucks.com. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Manhattan Hospital Listings". New York Hospitals. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Best Hospitals in New York, N.Y." US News & World Report. July 26, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Greenwich Village, New York City-Manhattan, New York Zip Code Boundary Map (NY)". United States Zip Code Boundary Map (USA). Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Patchin". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: Village". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Location Details: West Village". USPS.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Greenwich Village / Soho – MN 02" (PDF). Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2016.

- ^ “From a Joke, a School Is Born in the Village”, New York Times, September 18, 2008

- ^ “Parents ‘work hard and take a risk’ to form a high school” Archived September 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Villager, September 24, 2008

- ^ “New private high school find home in Soho on Vandam St.” Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Villager, November 21, 2008

- ^ "The New School". Newschool.edu. August 25, 2010. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ "The New School: Johnson Design Center". Newschool.edu. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ Peter Cooper. Columbia University Libraries. 1891. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ Henry Whitney Bellows Lecture (PDF). Cooper Union Engineering Faculty. 1999. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ "About the Jefferson Market Library". The New York Public Library. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "About the Hudson Park Library". The New York Public Library. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Subway Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. October 21, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- ^ "Manhattan Bus Map" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. July 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Biography, Edward Albee Society. Accessed June 21, 2016. "Albee spent the 1950s living in Greenwich Village in a number of apartments and working a variety of odd jobs (for example, a telegram delivery person) to supplement his monthly stipend from a trust fund left for him by his paternal grandmother."

- ^ Budin, Jeremiah. "Alec Baldwin Expands Devonshire House Empire with 1BR", Curbed New York, September 5, 2013. Accessed June 21, 2016. "First Hathaway wants out of Dumbo, then Harris moves into Harlem, and now Alec Baldwin is staying right where he is in Greenwich Village and just buying up more space in the building he already lives in."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "The 2014 NYC Celebrity Star Map Infographic", Address Report, May 12, 2014. Accessed November 3, 2016.

- ^ Spokony, Sam. "Richard Barone is 'cool' with where he is right now", The Villager, October 25, 2012. Accessed June 21, 2016. "And as a longtime Greenwich Village resident, Barone has certainly been just as active: He's maintained a presence as a community advocate, contributed valuable effort to a local nonprofit, and recently took on a professorship at New York University."

- ^ Bell, Arthur (October 31, 1977). "A Talk on the Wild Side". The Village Voice. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

During heavy drinking periods, he seldom left his Greenwich Village apartment

- ^ Hainey, Michael. "Nate Berkus and Jeremiah Brent Share Their New York City Apartment and Daughter Poppy’s Nursery; In Greenwich Village, star designers Nate Berkus and Jeremiah Brent—and their daughter, Poppy—settle in to family life in spirited style", Architectural Digest, September 30, 2015. Accessed June 21, 2016.

- ^ Marino, Vivian. "Sarah Jessica Parker’s House Sells for $18.25 Million", The New York Times, July 3, 2015. Accessed June 21, 2016. "A 25-foot-wide Greek Revival-style townhouse on a prime tree-lined street in Greenwich Village that Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick bought, refurbished and promptly returned to the market, sold for $18,250,000 and was the most expensive closed sale of the week, according to city records."

- ^ a b Johnson, Richard (November 9, 2006). "Page Six: Secure Location". New York Post. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Kurutz, Steven. "What Do Anna Wintour and Bob Dylan Have in Common? This Secret Garden", The New York Times, September 28, 2016. Accessed November 3, 2016. "The house is part of the Macdougal-Sullivan Gardens Historic District, a landmarked community of 21 row homes, with 11 lining Macdougal Street and 10 running parallel on Sullivan Street."

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang. "Jacob Cohen, 74, Psychologist And Pioneer in Statistical Studies", The New York Times, February 7, 1998. Accessed June 21, 2016. "Dr. Jacob Cohen, a professor emeritus of psychology at New York University who reinvented some of the ways researchers in the behavioral sciences gather and interpret their statistics, died on Jan. 20 at St. Vincent's Hospital and Medical Center. He was 74 and a resident of Greenwich Village and South Wellfleet on Cape Cod in Massachusetts."

- ^ "Secure Location". Bowery Boogie. Archived from the original on December 27, 2009.

- ^ a b David, Mark (April 24, 2013). "Claire Danes Snags NYC Townhouse". Variety. Retrieved August 13, 2018.

- ^ Bosworth, Patricia (February 3, 2014). "The Shadow King". Vanity Fair.

- ^ Turner, Christopher. Adventures in the Orgasmatron, excerpted in The New York Times, September 23, 2011. Accessed November 2, 2016. "Greenwich Village bohemians, such as the writers Max Eastman and Floyd Dell, the anarchist Emma Goldman, who had been "deeply impressed by the lucidity" of Freud's 1909 lectures, and Mabel Dodge, who ran an avant-garde salon in her apartment on Fifth Avenue, adapted psychoanalysis to create their own free-love philosophy."

- ^ "Actor's toughest role". CNN. 2004. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- ^ Seabrook, John (June 11, 2007). "Transplant". The New Yorker.

- ^ "Crystal Eastman (1881–1928); Radical Feminist from Greenwich Village", College of Staten Island. Accessed November 2, 2016. "Crystal Eastman was born in Marlborough, Mass. on June 25, 1881. She graduated from Vassar College Poughkeepsie, N.Y. in 1903 and moved to Greenwich Village that same year."

- ^ "Andrew Garfield Biography". IMDb. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ Greenberg, Hank (December 16, 2009). Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life. Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 9781461662389 – via Google Books.

- ^ "No. 50 West 10th Street – A Carriage House with Broadway History", Daytonian in Manhattan, June 14, 2011. Accessed November 3, 2016. "In 1949 Evans purchased No. 50 West 10th, starting its tradition as the home to celebrated theatrical names. When Evans sold the house in May 1965 for $120,000, it was the illustrious playwright Edward Albee who moved in.... Only three years later Albee sold the house to composer and lyricist Jerry Herman for $210,000."

- ^ Gaffney, Adrienne. "Inside Edward Hopper's Private World". Architectural Digest. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ "Secure Location". New York Post. December 3, 2009.

- ^ "17 LGBT landmarks of Greenwich Village". 6sqft. May 30, 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (November 10, 1996). "For Rent: 3-Floor House, 9 1/2 Ft. Wide, $6,000 a Month". The New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ Doonan, Simon. "Julianne Moore’s Verdant New York City Garden: After a false start designing her own garden, the actress taps Brian Sawyer to give her a playful, romantic sanctuary in the heart of the West Village", Architectural Digest, February 29, 2012. Accessed November 3, 2016. "'I had several goes at the garden, and it was just a disaster,' says the affable, distinctly un-Hollywood Moore, gesturing toward her 1,000-square-foot Greenwich Village backyard."

- ^ Grimberg, Salomon; Muray, Nickolas (October 26, 2006). I Will Never Forget You: Frida Kahlo and Nickolas Muray. Chronicle Books. ISBN 9780811856928 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wilonsky, Robert. "Lilith Fare: A Chat with Bebe Neuwirth", Dallas Observer, May 25, 2007. Accessed November 3, 2016. "She doesn't have cable and only watches TV at night on the few broadcast stations she can pick up in her home in Greenwich Village."

- ^ Grove, Lloyd; Morgan, Hudson (July 15, 2005). "'GMA' Hails a High-Flying Competitor". New York Daily News. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

If movie star Edward Norton never hears another mention of the West Side stadium, it'll be too soon. At Wednesday night's Friends of the High Line summer benefit, the West Village resident voiced his disdain....