| Leyes de nacionalidad y ciudadanía irlandesas de 1956 a 2004 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Oireachtas | |

| |

| Promulgado por | Gobierno de Irlanda |

| Estado: legislación vigente | |

La ley de nacionalidad irlandesa está contenida en las disposiciones de las Leyes de nacionalidad y ciudadanía irlandesas de 1956 a 2004 y en las disposiciones pertinentes de la Constitución irlandesa . Una persona puede ser un ciudadano irlandés [1] por nacimiento, ascendencia, matrimonio con un ciudadano irlandés o por naturalización . La ley otorga la ciudadanía a las personas nacidas en Irlanda del Norte en las mismas condiciones que las nacidas en la República de Irlanda .

Historia [ editar ]

Constitución del Estado Libre de Irlanda (1922) [ editar ]

La ley de ciudadanía irlandesa se origina en el artículo 3 de la Constitución del Estado Libre de Irlanda, que entró en vigor el 6 de diciembre de 1922; sólo se aplicó a nivel nacional hasta la promulgación de la Constitución (enmienda núm. 26) Ley de 1935 el 5 de abril de 1935. [2] [3] Cualquier persona domiciliada en la isla de Irlanda el 6 de diciembre de 1922 era un ciudadano irlandés si:

- nació en la isla de Irlanda;

- al menos uno de sus padres nació en la isla de Irlanda; o

- había residido habitualmente en la isla de Irlanda durante al menos siete años;

excepto que "cualquier persona que sea ciudadana de otro Estado" podría "[elegir] no aceptar" la ciudadanía irlandesa. (El artículo también establece que "las condiciones que rigen la futura adquisición y terminación de la ciudadanía en el Estado Libre de Irlanda [...] serán determinadas por la ley".)

Si bien la Constitución se refiere a los domiciliados "en el área de jurisdicción del Estado Libre de Irlanda", esto se interpretó en el sentido de toda la isla. Esto se debió a que, en virtud del Tratado angloirlandés de 1921 , Irlanda del Norte tenía derecho a optar por salir del Estado libre irlandés en el plazo de un mes desde la creación del Estado libre irlandés. [4] El 7 de diciembre de 1922, el día después de la creación del Estado Libre de Irlanda, Irlanda del Norte ejerció esta opción. [4] Sin embargo, la "brecha de veinticuatro horas" significaba que todas las personas que residían habitualmente en Irlanda del Norte el 6 de diciembre de 1922 eran consideradas ciudadanas irlandesas según el artículo 3 de la Constitución. [4] [5]

Las autoridades británicas consideraron que el estatus del Estado Libre Irlandés como un Dominio dentro de la Commonwealth británica significaba que un "ciudadano del Estado Libre Irlandés" era simplemente un miembro de la categoría más amplia de "súbdito británico"; esta interpretación podría estar respaldada por la redacción del artículo 3 de la Constitución, que establece que los privilegios y obligaciones de la ciudadanía irlandesa se aplican "dentro de los límites de la jurisdicción del Estado libre irlandés". Sin embargo, las autoridades irlandesas rechazaron repetidamente la idea de que sus ciudadanos tuvieran el estatus adicional de "súbditos británicos". [6] Además, mientras que el juramento de lealtad para los miembros del Oireachtas, según lo establecido en el artículo 17 de la Constitución, y según lo exige el art. 4 del Tratado, referido a "la ciudadanía común de Irlanda con Gran Bretaña", un memorando de 1929 sobre nacionalidad y ciudadanía preparado por el Departamento de Justicia a solicitud del Departamento de Relaciones Exteriores para la Conferencia sobre el Funcionamiento de la Legislación de Dominio declaró :

La referencia a "ciudadanía común" en el Juramento significa poco o nada. "Ciudadanía" no es un término de la ley inglesa en absoluto. De hecho, no existe una "ciudadanía común" en toda la Commonwealth británica: el "ciudadano" indio es tratado por el "ciudadano" australiano como un extranjero indeseable. [7]

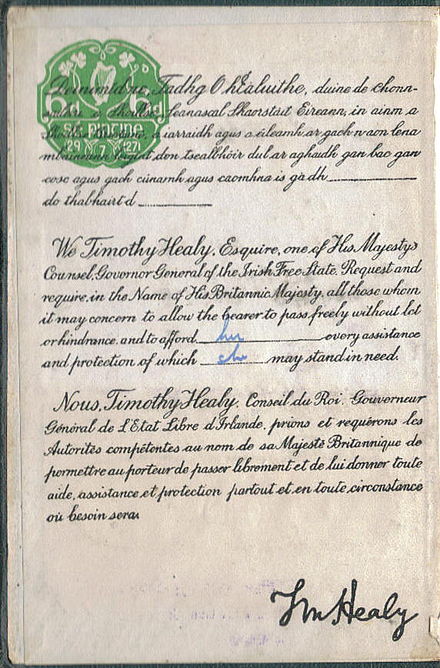

Los pasaportes irlandeses se emitieron a partir de 1923 y al público en general a partir de 1924, pero el gobierno británico se opuso a ellos y a su redacción durante muchos años. El uso de un pasaporte del Estado Libre de Irlanda en el extranjero, si se requiere la asistencia consular de una embajada británica, puede generar dificultades administrativas.

Ley de nacionalidad y ciudadanía irlandesa de 1935 [ editar ]

La Constitución de 1922 estipulaba la ciudadanía sólo para los que vivían el 6 de diciembre de 1922. No se establecían disposiciones para los nacidos después de esta fecha. Como tal, se trataba de una disposición temporal que requería la promulgación de una ley de ciudadanía en toda regla que se hizo mediante la Ley de nacionalidad y ciudadanía irlandesa de 1935 . Esta ley disponía, entre otras cosas:

- Ciudadanía irlandesa por nacimiento para cualquier persona nacida en el Estado Libre de Irlanda a partir del 6 de diciembre de 1922;

- Ciudadanía irlandesa por descendencia para cualquier persona nacida fuera del Estado Libre de Irlanda el 6 de diciembre de 1922 o después, y antes de la aprobación de la Ley de 1935 (10 de abril de 1935) y cuyo padre , el día de su nacimiento, era ciudadano irlandés;

- Ciudadanía irlandesa por descendencia para cualquier persona nacida fuera del Estado Libre de Irlanda a partir de la aprobación de la Ley de 1935 (10 de abril de 1935) y cuyo padre era ciudadano irlandés en el momento de su nacimiento. Si el padre había nacido fuera del Estado Libre de Irlanda, dicho nacimiento tenía que registrarse en el registro de nacimientos de Irlanda del Norte o extranjeros. "Se impuso un requisito de registro para los nacidos a partir de la aprobación de la ley (10 de abril de 1935) fuera del Estado Libre de Irlanda de un padre nacido fuera del Estado Libre de Irlanda (incluida Irlanda del Norte) o de un ciudadano naturalizado"; [8]

- un procedimiento de naturalización; y

- desnaturalización automática para cualquier persona que se haya convertido en ciudadano de otro país al cumplir los 21 años de edad o después.

La provisión de ciudadanía por descendencia tuvo el efecto, dada la interpretación mencionada anteriormente, de otorgar la ciudadanía a los nacidos en Irlanda del Norte después del 6 de diciembre de 1922 siempre que su padre hubiera residido en cualquier lugar de Irlanda en dicha fecha. Sin embargo, este derecho automático se limitó a la primera generación, y la ciudadanía de las generaciones posteriores requirió el registro y la renuncia de cualquier otra ciudadanía que se tuviera a la edad de 21 años. La combinación de los principios de nacimiento y descendencia en la ley respetó la territorialidad del estado. frontera, con los residentes de Irlanda del Norte tratados "de manera idéntica a las personas de origen o ascendencia irlandesa que residían en Gran Bretaña o en un país extranjero". [9]Según Brian Ó Caoindealbháin, la Ley de 1935 era, por tanto, compatible con las fronteras existentes en el estado, respetándolas y, de hecho, reforzándolas. [10]

La ley también preveía el establecimiento del Registro de Nacimientos Extranjeros .

Además, la Ley de 1935 fue un intento de afirmar la soberanía del Estado Libre y la naturaleza distinta de la ciudadanía irlandesa, y de poner fin a la ambigüedad sobre las relaciones entre la ciudadanía irlandesa y el estatus de súbdito británico. No obstante, Londres siguió reconociendo a los ciudadanos irlandeses como súbditos británicos hasta la aprobación de la Ley de Irlanda de 1949, que reconocía, como una clase distinta de personas, a los "ciudadanos de la República de Irlanda". [6] [11]

A partir de 1923, se crearon algunos nuevos derechos económicos para los ciudadanos irlandeses. La Ley de Tierras de 1923 permitió a la Comisión de Tierras de Irlanda negarse a permitir la compra de tierras agrícolas por parte de ciudadanos no irlandeses; Durante la guerra comercial anglo-irlandesa, la Ley de Control de Manufacturas de 1932 requería que al menos el 50% de la propiedad de las empresas registradas en Irlanda debía estar en manos de ciudadanos irlandeses. “La ley de 1932 definió a un 'nacional' irlandés como una persona que había nacido dentro de los límites del Estado Libre de Irlanda o que había residido en el estado durante cinco años antes de 1932 ... Según los términos de las Leyes de Control de Manufacturas, todos los residentes de Irlanda del Norte se consideraron extranjeros; de hecho, es posible que la legislación se haya diseñado explícitamente teniendo esto en cuenta ". [12]

Constitución de Irlanda (1937) [ editar ]

La Constitución de Irlanda de 1937 simplemente mantuvo el organismo de ciudadanía anterior, y también disponía, como lo había hecho la constitución anterior, que la adquisición y pérdida de la ciudadanía irlandesa debía ser regulada por ley.

Con respecto a Irlanda del Norte, a pesar de la naturaleza irredentista y las afirmaciones retóricas de los artículos 2 y 3 de la nueva constitución , la compatibilidad de la ley de ciudadanía irlandesa con las fronteras del estado permaneció inalterada. [13]

Ley de nacionalidad y ciudadanía irlandesa de 1956 [ editar ]

En 1956, el parlamento irlandés promulgó la Ley de ciudadanía y nacionalidad irlandesa de 1956 . Esta Ley derogó la Ley de 1935 y sigue siendo, aunque muy modificada, la base de la ley de ciudadanía irlandesa. Este acto, según Ó Caoindealbháin, alteró radicalmente el tratamiento de los residentes de Irlanda del Norte en la ley de ciudadanía irlandesa. Con la promulgación de la Ley de la República de Irlanda en 1948 y la posterior aprobación de la Ley de Irlandapor el gobierno británico en 1949, se aseguró la independencia constitucional del estado, facilitando la resolución de la posición insatisfactoria desde una perspectiva nacionalista irlandesa por la cual los nacimientos en Irlanda del Norte se asimilaban a nacimientos "extranjeros". El gobierno irlandés fue explícito en su objetivo de enmendar esta situación, buscando extender la ciudadanía lo más ampliamente posible a Irlanda del Norte, así como a los emigrantes irlandeses y sus descendientes en el extranjero. [14]

Por lo tanto, la ley preveía la ciudadanía irlandesa para cualquier persona nacida en la isla de Irlanda, antes o después de la independencia. Las únicas limitaciones a esta disposición eran que cualquier persona nacida en Irlanda del Norte no era automáticamente un ciudadano irlandés, sino que tenía derecho a ser ciudadano irlandés y que un hijo de alguien con derecho a inmunidad diplomática en el estado no se convertiría en ciudadano irlandés. La ley también preveía la ciudadanía indefinida por descendencia y la ciudadanía mediante registro para las esposas (pero no los maridos) de los ciudadanos irlandeses.

El tratamiento de los residentes de Irlanda del Norte en estas secciones tuvo una importancia considerable para los límites territoriales del estado, dado que su "efecto sensacional ... fue conferir, a los ojos de la ley irlandesa, ciudadanía a la gran mayoría de la población de Irlanda del Norte". [15] La compatibilidad de esta innovación con el derecho internacional, según Ó Caoindealbháin era dudosa, "dado su intento de regular la ciudadanía de un territorio externo ... Al buscar extender la ciudadanía jus soli más allá de la jurisdicción del estado, la Ley de 1956 buscó abiertamente subvertir el límite territorial entre el Norte y el Sur ". Las implicaciones de la Ley fueron fácilmente reconocidas en Irlanda del Norte, con Lord Brookeborough presentando una moción en elEl Parlamento de Irlanda del Norte repudia "el intento gratuito ... de infligir la nacionalidad republicana irlandesa no deseada al pueblo de Irlanda del Norte". [dieciséis]

Sin embargo, la ciudadanía irlandesa continuó extendiéndose a los habitantes de Irlanda del Norte durante más de 40 años, lo que representa, según Ó Caoindealbháin, "una de las pocas expresiones prácticas del irredentismo del estado irlandés". Ó Caoindealbháin concluye, sin embargo, que el Acuerdo del Viernes Santo de 1998 alteró significativamente las implicaciones territoriales de la ley de ciudadanía irlandesa, aunque de manera algo ambigua, a través de dos disposiciones clave: la renuncia al reclamo territorial constitucional sobre Irlanda del Norte y el reconocimiento de "la primogenitura de todos los habitantes de Irlanda del Norte a identificarse y ser aceptados como irlandeses o británicos o ambos, según lo deseen ", y que" ambos gobiernos aceptan su derecho a poseer tanto la ciudadanía británica como la irlandesa ".

En cuanto al derecho internacional, Ó Caoindealbháin afirma que, si bien es el intento de conferir la ciudadanía extraterritorialmente sin el acuerdo del estado afectado lo que representa una violación del derecho internacional (no la extensión real), la Ley de 1956 "coexiste incómodo con los términos del Acuerdo y, por extensión, la aceptación oficial por parte del estado irlandés de la frontera actual. Si bien el Acuerdo reconoce que la ciudadanía irlandesa es un derecho de nacimiento de los nacidos en Irlanda del Norte, deja en claro que su aceptación es un cuestión de elección individual. En cambio, la Ley de 1956 sigue ampliando la ciudadanía automáticamente en la mayoría de los casos, lo que, en efecto, entra en conflicto con el estatuto convenido de la frontera y el principio de consentimiento ". [13]

Leyes de nacionalidad y ciudadanía irlandesas de 1986 y 1994 [ editar ]

En 1986, la Ley de 1956 fue modificada por la Ley de ciudadanía y nacionalidad irlandesa de 1986 . Esta ley se ocupó principalmente de eliminar varias disposiciones discriminatorias por motivos de género de la legislación de 1956 y, por lo tanto, preveía la ciudadanía mediante el registro de las esposas y maridos de ciudadanos irlandeses.

La Ley también restringió la ciudadanía indefinida por descendencia otorgada por la Ley de 1956 al fechar la ciudadanía de la tercera, cuarta y posteriores generaciones de emigrantes irlandeses nacidos en el extranjero, desde el registro y no desde el nacimiento. Esto limitó los derechos de la cuarta generación y las siguientes a la ciudadanía a aquellos cuyos padres habían sido registrados antes de su nacimiento. La ley preveía un período de transición de seis meses durante el cual se seguirían aplicando las antiguas normas. Tal fue el aumento en el volumen de solicitudes de registro de emigrantes irlandeses de tercera, cuarta y posterior generación, que se promulgó la Ley de nacionalidad y ciudadanía irlandesa de 1994 para tratar con las personas que solicitaron el registro dentro del período de seis meses pero que no pudieron registrarse a tiempo.

Jus soli y la Constitución [ editar ]

Hasta finales de la década de 1990, el jus soli , en la República, se mantenía como una cuestión de ley, las únicas personas que tenían derecho constitucional a la ciudadanía del estado irlandés después de 1937 eran aquellas que habían sido ciudadanos del Estado Libre de Irlanda antes de su disolución. Sin embargo, como parte del nuevo acuerdo constitucional generado por el Acuerdo del Viernes Santo , el nuevo artículo 2 introducido en 1999 por la Decimonovena Enmienda de la Constitución de Irlanda disponía (entre otras cosas) que:

It is the entitlement and birthright of every person born in the island of Ireland, which includes its islands and seas, to be part of the Irish nation. That is also the entitlement of all persons otherwise qualified in accordance with law to be citizens of Ireland.

The introduction of this guarantee resulted in the enshrinement of jus soli as a constitutional right for the first time.[17] In contrast the only people entitled to British citizenship as a result of the Belfast Agreement are people born in Northern Ireland to Irish citizens, British citizens and permanent residents.

If immigration was not on the political agenda in 1998, it did not take long to become so afterwards. Indeed, soon after the agreement, the already rising strength of the Irish economy reversed the historic pattern of emigration to one of immigration, a reversal which in turn resulted in a large number of foreign nationals claiming a right to remain in the state based on their Irish-born citizen children.[18] They did so on the basis of a 1989 Supreme Court judgment in Fajujonu v. Minister for Justice where the court prohibited the deportation of the foreign parents of an Irish citizen. In January 2003, the Supreme Court distinguished the earlier decision and ruled that it was constitutional for the Government to deport the parents of children who were Irish citizens.[19] This latter decision would have been thought to put the matter to rest but concerns remained about the propriety of the (albeit indirect) deportation of Irish citizens and what was perceived as the overly generous provisions of Irish nationality law.

In March 2004, the government introduced the draft Bill for the Twenty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland to remedy what the Minister for Justice, Michael McDowell, described as an "abuse of citizenship" whereby citizenship was "conferred on persons with no tangible link to the nation or the State whether of parentage, upbringing or of long-term residence in the State".[20] The Amendment did not propose to change the wording of Articles 2 and 3 as introduced by the Nineteenth Amendment, but instead to insert a clause clawing back the power to determine the future acquisition and loss of Irish citizenship by statute, as previously exercised by parliament before the Nineteenth amendment. The government also cited concerns about the Chen case, then before the European Court of Justice, in which a Chinese woman who had been living in Wales had gone to give birth in Northern Ireland on legal advice. Mrs. Chen then pursued a case against the British Home Secretary to prevent her deportation from the United Kingdom on the basis of her child's right as a citizen of the European Union (derived from the child's Irish citizenship) to reside in a member state of the Union. (Ultimately Mrs. Chen won her case, but this was not clear until after the result of the referendum.) Both the proposed amendment and the timing of the referendum were contentious but the result was decisively in favour of the proposal; 79% of those voting voted yes, on a turnout of 59%.[21]

The effect of the amendment was to prospectively restrict the constitutional right to citizenship by birth to those who are born on the island of Ireland to at least one parent who is (or is someone entitled to be) an Irish citizen. Those born on the island of Ireland before the coming into force of the amendment continue to have a constitutional right to citizenship. Moreover, jus soli primarily existed in legislation and it remained, after the referendum, for parliament to pass ordinary legislation that would modify it. This was done by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2004 (the effects of which are detailed above). It remains, however, a matter for the legislature and unrestricted jus soli could be re-established by ordinary legislation without a referendum.

Acquisition of citizenship[edit]

At birth[edit]

A person born on the island of Ireland on or after 1 January 2005:[22]

- is automatically an Irish citizen if he or she is not entitled to the citizenship of any other country;[23] or

- is entitled to be an Irish citizen if at least one of his or her parents is:

- an Irish citizen (or someone entitled to be an Irish citizen);[24]

- a British citizen;[25]

- a resident of the island of Ireland who is entitled to reside in either the Republic or in Northern Ireland without any time limit on that residence;[26] or

- a legal resident of the island of Ireland for three out of the 4 years preceding the child's birth (although time spent as a student or as an asylum seeker does not count for this purpose).[27]

A person who is entitled to become an Irish citizen becomes an Irish citizen if:

- he or she does any act that only Irish citizens are entitled to do; or

- any act that only Irish citizens are entitled to do is done on his or her behalf by a person entitled to do so.[28]

Dual citizenship is permitted under Irish nationality law.

December 1999 to 2005[edit]

Ireland previously had a much less diluted application of jus soli (the right to citizenship of the country of birth) which still applies to anyone born on or before 31 December 2004. Although passed in 2001, the applicable law was deemed enacted on 2 December 1999[29] and provided that anyone born on the island of Ireland is:

- entitled to be an Irish citizen and

- automatically an Irish citizen if he or she was not entitled to the citizenship of any other country.

Prior to 1999[edit]

The previous legislation was largely replaced by the 1999 changes, which were retroactive in effect. Before 2 December 1999, the distinction between Irish citizenship and entitlement to Irish citizenship rested on the place of birth. Under this regime, any person born on the island of Ireland was:

- automatically an Irish citizen if born:

- on the island of Ireland before 6 December 1922,

- in the territory which currently comprises the Republic of Ireland, or

- in Northern Ireland on or after 6 December 1922 with a parent who was an Irish citizen at the time of birth;

- entitled to be an Irish citizen if born in Northern Ireland and not automatically an Irish citizen.[30]

The provisions of the 1956 Act were, in terms of citizenship by birth, retroactive and replaced the provisions of the previous legislation, the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1935. Under that legislation, those born in Northern Ireland on or after 6 December 1922 did not have an entitlement to Irish citizenship by birth.[citation needed]Citizenship of the Irish Free State was determined under the 1922 constitution, as amended by the Constitution (Amendment No. 26) Act 1935.

Children of diplomats[edit]

Like most countries, Ireland does not normally grant citizenship to the children of diplomats. This does not apply, however, when a diplomat parents a child with an Irish citizen, a British citizen or a permanent resident.[31] In 2001, Ireland enacted a measure which allowed the children of diplomats to register as Irish citizens if they chose to do so; however, this was repealed three years later.[32] The option to register remains for those born to diplomats before 2005.

By descent[edit]

A person is an Irish citizen by descent if, at the time of his or her birth, at least one of his or her parents was an Irish citizen.[33] In cases where at least one parent was an Irish citizen born in the island of Ireland[33] or an Irish citizen not born on the island of Ireland but resident abroad in the public service,[34] citizenship is automatic and dates from birth. In all other cases citizenship is subject to registration in the Foreign Births Register.[35]

Due to legislative changes introduced in 1986, the Irish citizenship, of those individuals requiring registration, dates from registration and not from birth, for citizenship registered on or after 1 January 1987.[36] Citizenship by registration had previously been back-dated to birth.

Anyone with an Irish citizen grandparent born on the island of Ireland is eligible for Irish citizenship. His or her parent would have automatically been an Irish citizen and their own citizenship can be secured by registering themselves in the Foreign Births Register. In contrast, those wishing to claim citizenship through an Irish citizen great-grandparent would be unable to do so unless their parents were placed into the Foreign Births Register. Their parents can transmit Irish citizenship to only those children born after they themselves were registered and not to any children born before registration.

Citizenship acquired through descent may be maintained indefinitely so long as each generation ensures its registration before the birth of the next.

By adoption[edit]

All adoptions performed or recognised under Irish law confer Irish citizenship on the adopted child (if not already an Irish citizen) if at least one of the adopters was an Irish citizen at the time of the adoption.[37]

By marriage[edit]

From 30 November 2005 (three years after the 2001 Citizenship Act came into force),[38] citizenship of the spouse of an Irish citizen must be acquired through the normal naturalisation process.[39] The residence requirement is reduced from 5 to 3 years in this case, and the spouse must intend to continue to reside in the island of Ireland.[40]

Previously, the law allowed for the spouses of most Irish citizens to acquire citizenship post-nuptially by registration without residence in the island of Ireland, or by naturalisation.[41]

- From 17 July 1956 to 31 December 1986,[42] the wife (but not the husband) of an Irish citizen (other than by naturalisation) could apply for post-nuptial citizenship. A woman who applied for this before marriage would become an Irish citizen upon marriage. This was a retrospective provision which could be applied to marriages made before 1956. However the citizenship granted was prospective only.[43]

- Between 1 July 1986[42] and 29 November 2005,[38] the spouse of an Irish citizen (other than by naturalisation, honorary citizenship or a previous marriage) could obtain post-nuptial citizenship after 3 years of subsisting marriage, provided the Irish spouse had held that status for at least 3 years. Like the provisions it replaced, the application of this regime was also retrospective.[44]

By naturalisation[edit]

The naturalisation of a foreigner as an Irish citizen is a discretionary power held by the Irish Minister for Justice. Naturalisation is granted on a number of criteria including good character, residence in the state and intention to continue residing in the state.

In principle the residence requirement is three years if married to an Irish citizen, and five years out of the last nine, including the year immediately before.[45] Time spent seeking asylum will not be counted. Nor will time spent as an illegal immigrant. Time spent studying in the state by a national of a non-EEA state (i.e. a state other than European Union Member States, Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein) will not count.

The Minister for Justice may waive the residency requirement for:

- the children of naturalised citizens;

- recognised refugees;

- stateless children;

- those resident abroad in the service of the Irish state; and

- people of "Irish descent or Irish associations".

By grant of honorary citizenship[edit]

Section 12 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 allows the President, on advice of the Government, to "… grant Irish citizenship as a token of honour to a person, or the child or grandchild of a person who, in the opinion of the Government, has done signal honour or rendered distinguished service to the nation."[46]

Although known as "honorary Irish citizenship", this is in fact legally a full form of citizenship, with entitlement to an Irish passport and the other rights of Irish citizenship on the same basis as a naturalised Irish citizen. This has been awarded only a few times.[47] The first twelve people to have had honorary Irish citizenship conferred on them are:[48][49]

- Alfred Chester Beatty (1957) – art collector, philanthropist and founder of the Chester Beatty Library

- Tiede Herrema (1975) (and his wife, Elizabeth Herrema) – Dutch businessman kidnapped by the Provisional IRA

- Tip O'Neill (1986) (and his wife, Mildred Anne Miller O'Neill) – Irish-American and Speaker of the United States House of Representatives

- Alfred Beit (1993) (and his wife Clementine Mabell Kitty Beit, née Freeman-Mitford) – art collector and owner of Russborough House

- Jack Charlton (1996) (and his wife Pat Charlton) – for his achievements as manager of the Republic of Ireland national football team

- Jean Kennedy Smith (1998) – former United States Ambassador to Ireland

- Derek Hill (1999) – artist who established the Tory Island school of painting

- Don Keough (2007) - former president of Coca-Cola (Atlanta)[citation needed]

Plans were made to grant honorary Irish citizenship to U.S. president John F. Kennedy during his visit to Ireland in 1963, but this was abandoned owing to legal difficulties in granting citizenship to a foreign head of state.[50]

Loss of citizenship[edit]

By renunciation[edit]

An Irish citizen may renounce his or her citizenship if he or she is:

- eighteen years or older,

- ordinarily resident abroad, and

- is, or is about to become, a citizen of another country.

Renunciation is done by lodging a declaration with the Minister for Justice. If the person is not already a citizen of another country it is only effective when he or she becomes such. Irish citizenship cannot be lost by the operation of the law of another country,[51] but foreign law may require a person to renounce Irish citizenship before acquiring foreign nationality (see Multiple citizenship#Multiple citizenship avoided).

An Irish citizen may not, except with the consent of the Minister, renounce their Irish citizenship during a time of war.[52]

An Irish citizen born on the island of Ireland who renounces Irish citizenship remains entitled to be an Irish citizen and may resume it upon declaration.[53]

While not positively stated in the Act, the possibility of renouncing Irish citizenship is provided to allow Irish citizens to be naturalised as citizens of foreign countries whose laws do not allow for multiple citizenship. The Minister of Justice may revoke the citizenship of a naturalised citizen if he or she voluntarily acquires the citizenship of another country (other than by marriage) after naturalisation but there is no provision requiring them to renounce any citizenship they previously held. Similarly, there is no provision of Irish law requiring citizens to renounce their Irish citizenship before becoming citizens of other countries.

By revocation of a certificate of naturalisation[edit]

A certificate of naturalisation may be revoked by the Minister for Justice. Once revoked the person to whom the certificate applies ceases to be an Irish citizen. Revocation is not automatic and is a discretionary power of the Minister. A certificate may be revoked if it was obtained by fraud or when the naturalised citizen to whom it applies:

- resides outside the state (or outside the island of Ireland in respect to naturalised spouses of Irish citizens) for a period exceeding seven years, otherwise than in the public service, without registering annually his or her intention to retain Irish citizenship (this provision does not apply to those who were naturalised owing to their "Irish descent or Irish associations");

- voluntarily acquires the citizenship of another country (other than by marriage); or

- "has, by any overt act, shown himself to have failed in his duty of fidelity to the nation and loyalty to the State".[54]

A notice of the revocation of a certificate of naturalisation must be published in Iris Oifigiúil (the official gazette of the Republic), but in the years of 2002 to 2012 (inclusive) no certificates of naturalisation were revoked.[55][56]

Dual citizenship[edit]

Ireland allows its citizens to hold foreign citizenship in addition to their Irish citizenship.

Simultaneous lines of Irish and UK citizenship for descendants of pre-1922 Irish emigrants[edit]

Some descendants of Irish persons who left Ireland before 1922 may have claims to both Irish and British citizenship.

Under section 5 of the UK's Ireland Act 1949, a person who was born in the territory of the future Republic of Ireland as a British subject, but who did not receive Irish citizenship under that Act's interpretation of either the 1922 Constitution of the Irish Free State or the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1935 (because he or she was no longer domiciled in the Republic on the day that the Free State constitution came into force and was not permanently resident there on the day of the 1935 law's enactment and was not otherwise registered as an Irish citizen) was deemed by British law to be a Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies.[57][58]

As such, many of those individuals and some of the descendants in the Irish diaspora of an Irish person who left Ireland before 1922 (and who was also not resident in 1935) may be registrable for Irish citizenship while also having a claim to British citizenship,[59] through any of:

- birth to the first generation emigrant,

- consular registration of later generation births by a married father who was considered a British citizen under British law, within one year of birth, prior to the British Nationality Act (BNA) 1981 taking effect,[60][61]

- registration, at any time in life, with Form UKF, of birth to an unwed father who was considered a British citizen under British law,[62] or

- registration, at any time in life, with Form UKM, of birth to a mother who was considered a British citizen under British law, between the BNA 1948 and the BNA 1981 effective dates, under the UK Supreme Court's 2018 Romein principle.[60][61]

In some cases, British citizenship may be available to these descendants in the Irish diaspora even when Irish citizenship registration is not, as in instances of failure of past generations to timely register in a local Irish consulate's Foreign Births Register before the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986 and before births of later generations.[59]

Citizenship of the European Union[edit]

Because Ireland forms part of the European Union, Irish citizens are also citizens of the European Union under European Union law and thus enjoy rights of free movement and have the right to vote in elections for the European Parliament.[63] When in a non-EU country where there is no Irish embassy, Irish citizens have the right to get consular protection from the embassy of any other EU country present in that country.[64][65] Irish citizens can live and work in any country within the EU as a result of the right of free movement and residence granted in Article 21 of the EU Treaty.[66]

Following the 2016 UK referendum on leaving the EU, which resulted in a vote to leave the European Union, there was a large increase in applications by British citizens (particularly from Northern Ireland) for Irish passports, so that they can retain their rights as EU citizens after the UK's withdrawal from the EU. There were 25,207 applications for Irish passports from Britons in the 12 months before the referendum, and 64,400 in the 12 months after. Applications to other EU countries also increased by a large percentage, but were numerically much smaller.[67]

Travel freedom of Irish citizens[edit]

Visa requirements for Irish citizens are travel restrictions placed upon citizens of the Republic of Ireland by the authorities of other states. In 2018, Irish citizens had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 185 countries and territories, jointly ranking the Irish passport 6th worldwide according to the Henley Passport Index.[68][69]

The Irish nationality is ranked ninth in Nationality Index (QNI). This index differs from the Visa Restrictions Index, which focuses on external factors including travel freedom. The QNI considers, in addition, to travel freedom on internal factors such as peace & stability, economic strength, and human development as well.[70]

See also[edit]

- British nationality law and the Republic of Ireland

- Citizenship of the European Union

- Common Travel Area

- Irish diaspora

- Jus sanguinis

- Irish passport

Notes[edit]

- ^ In Irish law the terms "nationality" and "citizenship" have equivalent meanings.

- ^ According to Article 3 of the Free State Constitution Irish citizenship had previously only "within the limits of the jurisdiction of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Éireann)". The Twenty Sixth amendment deleted the condition to extend the duties and right of Irish citizenship outside of the Free State.

- ^ Dáil Debates, 14 February 1935, Vol. 54 No. 12 Col. 2049, Constitution (Amendment No. 26) Bill, 1934, Second Stage, The President. [1]

- ^ a b c ‘Irish Nationality and Citizenship since 1922’ by Mary E. Daly, in ‘Irish Historical Studies’ Vol. 32, No. 127, May, 2001 (pp. 377-407)

- ^ In re Logue [1933] 67 ILTR 253. The decision resulted in changes being made the British Nationality Act 1948 by section 5 the Ireland Act 1949, to ensure that people who were domiciled in Northern Ireland on 6 December 1922 but were born elsewhere in Ireland would not fail to become a "citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies" merely because they were also an Irish citizen.

- ^ a b Brian Ó Caoindealbháin (2006) Citizenship and Borders: Irish Nationality Law and Northern Ireland. Centre for International Borders Research, Queen's University of Belfast and Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin. Accessed 04-06-09[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Extract from a memorandum on nationality and citizenship". Documents on Irish Foreign Policy. Royal Irish Academy. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- ^ Bauböck, Rainer, ed. (2006). Acquisition and Loss of Nationality: Policies and Trends in 15 European States. 2. Amsterdam University Press. p. 295. ISBN 9053569219.

- ^ Daly, Mary (2001) "Irish nationality and citizenship since 1922", Irish historical studies 32 (127): 377-407. Cited in Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- ^ Ó Caoindealbháin (2006), p.12

- ^ Síofra O'Leary (1996) Irish nationality law, in B Nascimbene (ed.), Nationality laws in the European Union, Milan: Butterworths, cited in Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- ^ Daly, Mary (2001) "Irish nationality and citizenship since 1922", Irish historical studies 32 (127):393

- ^ a b Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- ^ Brian Ó Caoindealbháin (2006) Citizenship and Borders: Irish Nationality Law and Northern Ireland. Centre for International Borders Research, Queen's University of Belfast and Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin

- ^ Kelly, JM (1994) The Irish constitution, 3rd ed. Dublin: Butterworths, cited in Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- ^ Daly, Mary (2001) “Irish nationality and citizenship since 1922”, Irish historical studies 32 (127): 377-407. Cited in Ó Caoindealbháin (2006)

- ^ This is clearly the view of Denham, McGuinness and Hardiman JJ, in Osayande v. Minister for Justice, a view which is supported by the current writers of Kelly.

- ^ The Irish Department of Justice granted leave to remain in the state to around 10,500 non-nationals between 1996 and February 2003 on the basis of their having an Irish born child – Department of Justice Press Release Archived 10 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Osayande v. Minister for Justice

- ^ Quoted from the Daíl debate.

- ^ See: Twenty-seventh Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland

- ^ This dates relates to the commencement date of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2004 and not the Twenty-seventh Amendment as is sometimes thought.

- ^ Section 6(3) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Sections 6(1), 6A(2)(b) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Sections 6(1) and 6A(2)(c) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Sections 6(1), 6A(2)(c) and (d) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Sections 6(1), 6A(1) and 6B of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Section 6(2) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ The relevant sections of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001 that was signed by the President on 5 June 2001, were backdated to apply from the changes made to Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Constitution under the Good Friday Agreement: Minister for Justice, John O'Donoghue, Seanad Debates volume 161 column 982 (8 December 1999) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- ^ Sections 6(1) and 7(1) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956, as enacted.

- ^ Section 6(6) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Section 6(4) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004, as inserted by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001 and later repealed by the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2004

- ^ a b Section 7(1) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Section 7(3)(b) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Section 7(3) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ While the 1986 act, which brought in the registration requirement, came into force on 1 July 1986, section 8 of the Act allowed for a six-month transitional period when people could still register under the old provisions. See: Minister for Justice, Máire Geoghegan-Quinn, Dáil debates volume 140 column 131 Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine (21 April 1994); Minister of State at the Department of the Environment, Liz McManus, Seanad Debates volume 142 column 1730 Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine (4 April 1995).

- ^ Section 11 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 as amended by section 175 of the Adoption Act 2010.

- ^ a b Section 4 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001 came into force on 30 November 2002 by ministerial order: Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001 (Commencement) Order, 2002.

- ^ The previous provisions having been repealed by section 4 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001.

- ^ Sections 15A(1)(e) and (f) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 as inserted by the section 33 of the Civil Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2011.

- ^ Section 8 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 and section 3 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986.

- ^ a b The Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986 came into force on 1 July 1986, section 8 of the Act allowed for a six-month transitional period during which both the new and old provisions were in force.

- ^ Section 8 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 as enacted.

- ^ Section 3 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986.

- ^ "Becoming an Irish citizen through naturalisation". www.gov.ie. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956 Section 12

- ^ Irish Abroad Unit. "Presidential Distinguished Service Award for the Irish Abroad" (PDF). Dublin: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. pp. Sec.5. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

This provision has been invoked on only a small number of occasions and recipients have included Jack Charlton, Jean Kennedy Smith, Alfred Beit, Alfred Chester Beatty and to Mr and Mrs Tip O’Neill.

- ^ McDowell, Michael (30 November 2004). "Irish Nationality and Citizenship Bill 2004: Report Stage (Resumed)". Dáil debates. p. Vol.593 No.5 p.23 c.1181. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ Anderson, Nicola (14 January 1999). "Artist made honorary citizen". Irish Independent. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

Dr Hill is just the 11th person to be awarded honorary citizenship since the foundation of the State.

- ^ Sniper threat sparked alert during 1963 Kennedy visit — The Irish Times newspaper article, 29 December 2006.

- ^ Section 21 of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004

- ^ "Renouncing or Reacquiring Irish citizenship". Department of Justice.

- ^ Section 6(5) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004.

- ^ Section 19(1)(b) of the Irish Nationality and Citizenship Acts 1956 to 2004

- ^ See the Official journal's Website. The period reflects the length of the Gazette's availability online.

- ^ "PQ: NATURALISATION APPLICATIONS (REVOKED)". NASC The Irish Immigrant Support Centre. 28 May 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- ^ R. F. V. Heuston (January 1950). "British Nationality and Irish Citizenship". International Affairs. 26 (1): 77–90. doi:10.2307/3016841. JSTOR 3016841.

- ^ "Ireland Act: Section 5", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1949 c. 41 (s. 5)

- ^ a b Daly, Mary E. (May 2001). "Irish Nationality and Citizenship since 1922". Irish Historical Studies. Cambridge University Press. 32 (127): 395, 400, 406. JSTOR 30007221.

- ^ a b Khan, Asad (23 February 2018). "Case Comment: The Advocate General for Scotland v Romein (Scotland) [2018] UKSC 6, Part One". UK Supreme Court Blog.

- ^ a b The Advocate General for Scotland (Appellant) v Romein (Respondent) (Scotland) [2018] UKSC 6, [2018] A.C. 585 (8 February 2018), Supreme Court (UK)

- ^ "Nationality: Registration as a British Citizen" (PDF). Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association. 14 August 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- ^ "Ireland". European Union. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Article 20(2)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

- ^ Rights abroad: Right to consular protection: a right to protection by the diplomatic or consular authorities of other Member States when in a non-EU Member State, if there are no diplomatic or consular authorities from the citizen's own state (Article 23): this is due to the fact that not all member states maintain embassies in every country in the world (14 countries have only one embassy from an EU state). Antigua and Barbuda (UK), Barbados (UK), Belize (UK), Central African Republic (France), Comoros (France), Gambia (UK), Guyana (UK), Liberia (Germany), Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (UK), San Marino (Italy), São Tomé and Príncipe (Portugal), Solomon Islands (UK), Timor-Leste (Portugal), Vanuatu (France)

- ^ "Treaty on the Function of the European Union (consolidated version)" (PDF). Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Morris, Chris (29 September 2017). "Brexit: Are more British nationals applying for dual nationality in the EU? - BBC News". BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ Ranks are assigned using dense ranking. A standard ranking places the Irish passport joint 16th.

- ^ "Global Ranking - Henley Passport Index 2018". Henley & Partners. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "The 41 nationalities with the best quality of life". www.businessinsider.de. 6 February 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

References[edit]

- J.M. Kelly, The Irish Constitution 4th edn. by Gerard Hogan and Gerard Whyte (2002) ISBN 1-85475-895-0

- Brian Ó Caoindealbháin (2006) Citizenship and Borders: Irish Nationality Law and Northern Ireland. Centre for International Borders Research, Queen's University of Belfast and Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin

External links[edit]

- Irish Department of Justice: Citizenship government website

- Repealed Acts of the Irish Free State:

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1935

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship (Amendment) Act 1937

- Acts in force:

- Irish Nationality & Citizenship Acts 1956-2004 (unofficial consolidated version) - pdf format

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1956

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1986

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 1994

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2001

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Act 2004

- Information on Irish citizenship from the Citizens Information Board

- Wives, mothers and citizens - the treatment of women in the 1935 Nationality & Citizenship Act

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Bill, 1985: Second Stage

- Irish Nationality and Citizenship Bill, 1994: Second Stage