Melbourne

| Melbourne Victoria | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

From top, left to right: Flinders Street Station, Shrine of Remembrance, Federation Square, Melbourne Cricket Ground, Royal Exhibition Building, the Melbourne skyline. | |||||||||

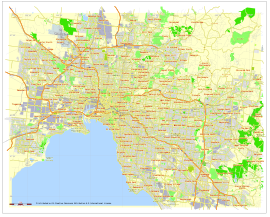

Map of Melbourne, Australia, printable and editable | |||||||||

| Coordinates | 37°48′49″S 144°57′47″E / 37.81361°S 144.96306°ECoordinates: 37°48′49″S 144°57′47″E / 37.81361°S 144.96306°E | ||||||||

| Population | 5,159,211 (2020)[1] (2nd) | ||||||||

| • Density | 516.282/km2 (1,337.17/sq mi) | ||||||||

| Established | 30 August 1835 | ||||||||

| Elevation | 31 m (102 ft) | ||||||||

| Area | 9.993 km 2 (3.858,3 millas cuadradas) (GCCSA) [2] | ||||||||

| Zona horaria | AEST ( UTC + 10 ) | ||||||||

| • Verano ( DST ) | AEDT ( UTC + 11 ) | ||||||||

| Localización | |||||||||

| LGA (s) | 31 municipios en el área metropolitana de Melbourne | ||||||||

| condado | Grant , Bourke , Mornington | ||||||||

| Electorado (s) estatal | 55 distritos y regiones electorales | ||||||||

| División (es) federal | 23 Divisiones | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Melbourne (/ˈmɛlbərn/ MEL-bərn,[note 1] locally /ˈmɛlbən/ (![]() listen)) is the capital and most-populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania.[1] Its name generally refers to a 9,993 km2 (3,858 sq mi) área metropolitana conocida como Greater Melbourne , [9] que comprende una aglomeración urbana de 31 municipios locales , [10] aunque el nombre también se usa específicamente para el municipio local de la ciudad de Melbourne basado en su área central de negocios . La ciudad ocupa gran parte de las costas norte y este de la bahía de Port Phillip y se extiende hacia la península de Mornington y el interior hacia el valle de Yarra , las cordilleras de Dandenong y Macedonia.. It has a population over 5 million (19% of the population of Australia, as per 2020), mostly residing to the east side of the city centre, and its inhabitants are commonly referred to as "Melburnians".[note 2]

listen)) is the capital and most-populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania.[1] Its name generally refers to a 9,993 km2 (3,858 sq mi) área metropolitana conocida como Greater Melbourne , [9] que comprende una aglomeración urbana de 31 municipios locales , [10] aunque el nombre también se usa específicamente para el municipio local de la ciudad de Melbourne basado en su área central de negocios . La ciudad ocupa gran parte de las costas norte y este de la bahía de Port Phillip y se extiende hacia la península de Mornington y el interior hacia el valle de Yarra , las cordilleras de Dandenong y Macedonia.. It has a population over 5 million (19% of the population of Australia, as per 2020), mostly residing to the east side of the city centre, and its inhabitants are commonly referred to as "Melburnians".[note 2]

Hogar de pueblos aborígenes durante más de 40.000 años, el área de Melbourne sirvió como un lugar de encuentro popular para los clanes locales de la nación Kulin , [13] Naarm es el nombre tradicional de Boon wurrung para la bahía de Port Phillip. [14] Se construyó un asentamiento penal de corta duración en Port Phillip, entonces parte de la colonia británica de Nueva Gales del Sur , en 1803, pero no fue hasta 1835, con la llegada de colonos libres de la Tierra de Van Diemen (en la actualidad Tasmania ), que se fundó Melbourne. [13] Se incorporó como corona.asentamiento en 1837, y el nombre del entonces primer ministro británico, William Lamb, segundo vizconde de Melbourne . [13] En 1851, cuatro años después de que la reina Victoria la declarara ciudad, Melbourne se convirtió en la capital de la nueva colonia de Victoria. [15] Durante la fiebre del oro victoriana de la década de 1850 , la ciudad entró en un largo período de auge que, a finales de la década de 1880, la había transformado en una de las metrópolis más grandes y ricas del mundo. [16] [17] Después de la federación de Australia en 1901, sirvió como sede interina del gobierno de la nueva nación hasta que Canberra se convirtió en la capital permanente en 1927.[18] En la actualidad, es un centro financiero líderen la región de Asia y el Pacífico y ocupa el puesto 23 a nivel mundial en el Índice de Centros Financieros Globales de 2021. [19]

Melbourne is home to many of Australia's best-known landmarks, such as the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the National Gallery of Victoria and the World Heritage-listed Royal Exhibition Building. Noted for its cultural heritage, the city gave rise to Australian rules football, Australian impressionism and Australian cinema, and has more recently been recognised as a UNESCO City of Literature and a global centre for street art, live music and theatre. It hosts major annual international events, such as the Gran Premio de Australia y el Abierto de Australia , y también fue sede de los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 1956 y los Juegos de la Commonwealth de 2006 . Melbourne se clasificó constantemente como la ciudad más habitable del mundo durante gran parte de la década de 2010. [20]

El aeropuerto de Melbourne , también conocido como el aeropuerto de Tullamarine, es el segundo aeropuerto más transitado de Australia, y el puerto de Melbourne es el puerto marítimo más transitado del país. [21] Su principal terminal ferroviaria metropolitana es la estación Flinders Street y su principal terminal ferroviaria regional y de autocares es la estación Southern Cross . También cuenta con la red de autopistas más extensa de Australia y la red de tranvías urbanos más grande del mundo . [22]

Historia

Historia temprana y fundación

Los aborígenes australianos han vivido en el área de Melbourne durante al menos 40.000 años. [23] Cuando llegaron los colonos europeos en el siglo XIX, al menos 20.000 personas Kulin de tres grupos lingüísticos distintos - Wurundjeri , Bunurong y Wathaurong - residían en el área. [24] [25] Era un lugar de encuentro importante para los clanes de la alianza de la nación Kulin y una fuente vital de alimentos y agua. [26] [27] En junio de 2021, los límites entre la tierra de dos de los propietarios tradicionales groups, the Wurundjeri and Bunurong, were agreed after being drawn up by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council. The borderline runs across the city from west to east, with the CBD, Richmond and Hawthorn included in Wurundjeri land, and Albert Park, St Kilda and Caulfield on Bunurong land.[28]

The first British settlement in Victoria, then part of the penal colony of New South Wales, was established by Colonel David Collins in October 1803, at Sullivan Bay, near present-day Sorrento. The following year, due to a perceived lack of resources, these settlers relocated to Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania) and founded the city of Hobart. It would be 30 years before another settlement was attempted.[29]

En mayo y junio de 1835, John Batman , un miembro destacado de la Asociación Port Phillip en Van Diemen's Land, exploró el área de Melbourne y luego afirmó haber negociado una compra de 600,000 acres (2,400 km 2 ) con ocho ancianos Wurundjeri. [26] [27] Batman seleccionó un sitio en la orilla norte del río Yarra , declarando que "este será el lugar para una aldea" antes de regresar a la Tierra de Van Diemen. [30] En agosto de 1835, otro grupo de colonos vandemonianos llegó al área y estableció un asentamiento en el sitio del actual Museo de Inmigración de Melbourne.. Batman y su grupo llegaron al mes siguiente y los dos grupos finalmente acordaron compartir el asentamiento, inicialmente conocido por el nombre nativo de Dootigala. [31] [32]

Batman's Treaty with the Aborigines was annulled by Richard Bourke, the Governor of New South Wales (who at the time governed all of eastern mainland Australia), with compensation paid to members of the association.[26] In 1836, Bourke declared the city the administrative capital of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, and commissioned the first plan for its urban layout, the Hoddle Grid, in 1837.[33] Known briefly as Batmania,[34] the settlement was named Melbourne on 10 April 1837 by Governor Richard Bourke[35] after the British Prime Minister, William Lamb, segundo vizconde de Melbourne , cuya sede era Melbourne Hall en la ciudad comercial de Melbourne , Derbyshire . Ese año, la oficina general de correos del asentamiento abrió oficialmente con ese nombre. [36]

Between 1836 and 1842, Victorian Aboriginal groups were largely dispossessed of their land by European settlers.[37] By January 1844, there were said to be 675 Aborigines resident in squalid camps in Melbourne.[38] The British Colonial Office appointed five Aboriginal Protectors for the Aborigines of Victoria, in 1839, however, their work was nullified by a land policy that favoured squatters who took possession of Aboriginal lands.[39] By 1845, fewer than 240 wealthy Europeans held all the pastoral licences then issued in Victoria and became a powerful political and economic force in Victoria for generations to come.[40]

Cartas de patente de la reina Victoria , emitidas el 25 de junio de 1847, declararon a Melbourne ciudad. [15] El 1 de julio de 1851, el distrito de Port Phillip se separó de Nueva Gales del Sur para convertirse en la colonia de Victoria, con Melbourne como su capital. [41]

Fiebre del oro victoriana

El descubrimiento de oro en Victoria a mediados de 1851 provocó una fiebre del oro , y Melbourne, el principal puerto de la colonia, experimentó un rápido crecimiento. En unos meses, la población de la ciudad casi se había duplicado de 25.000 a 40.000 habitantes. [42] Se produjo un crecimiento exponencial, y en 1865 Melbourne había superado a Sydney como la ciudad más poblada de Australia. [43]

An influx of intercolonial and international migrants, particularly from Europe and China, saw the establishment of slums, including Chinatown and a temporary "tent city" on the southern banks of the Yarra. In the aftermath of the 1854 Eureka Rebellion, mass public support for the plight of the miners resulted in major political changes to the colony, including improvements in working conditions across mining, agriculture, manufacturing and other local industries. At least twenty nationalities took part in the rebellion, giving some indication of immigration flows at the time.[44]

With the wealth brought in from the gold rush and the subsequent need for public buildings, a program of grand civic construction soon began. The 1850s and 1860s saw the commencement of Parliament House, the Treasury Building, the Old Melbourne Gaol, Victoria Barracks, the State Library, University of Melbourne, General Post Office, Customs House, the Melbourne Town Hall, St Patrick's cathedral, though many remained uncompleted for decades, with some still not finished as of 2018[update].

The layout of the inner suburbs on a largely one-mile grid pattern, cut through by wide radial boulevards and parklands surrounding the central city, was largely established[by whom?] in the 1850s and 1860s. These areas rapidly filled with the ubiquitous terrace houses, as well as with detached houses and grand mansions, while some of the major roads developed as shopping streets. Melbourne quickly became a major finance centre, home to several banks, the Royal Mint, and (in 1861) Australia's first stock exchange.[45]In 1855, the Melbourne Cricket Club secured possession of its now famous ground, the MCG. Members of the Melbourne Football Clubcodificó el fútbol australiano en 1859, [46] y en 1861 se celebró la primera carrera de la Copa de Melbourne . Melbourne adquirió su primer monumento público, la estatua de Burke and Wills , en 1864.

Con la fiebre del oro en gran parte terminada en 1860, Melbourne continuó creciendo gracias a la continua extracción de oro, como el principal puerto para exportar los productos agrícolas de Victoria (especialmente lana) y con un sector manufacturero en desarrollo protegido por altos aranceles. Una extensa red de ferrocarriles radiales se extendió por el campo desde finales de la década de 1850. La construcción comenzó en otros edificios públicos importantes en las décadas de 1860 y 1870, como el Tribunal Supremo , la Casa de Gobierno y el mercado Queen Victoria.. The central city filled up with shops and offices, workshops, and warehouses. Large banks and hotels faced the main streets, with fine townhouses in the east end of Collins Street, contrasting with tiny cottages down laneways within the blocks. The Aboriginal population continued to decline, with an estimated 80% total decrease by 1863, due primarily to introduced diseases (particularly smallpox[24]), frontier violence and dispossession of their lands.

Land boom and bust

La década de 1880 vio un crecimiento extraordinario: la confianza del consumidor, el fácil acceso al crédito y los fuertes aumentos en los precios de la tierra llevaron a una enorme cantidad de construcción. Durante este "boom terrestre", se dice que Melbourne se convirtió en la ciudad más rica del mundo, [16] y la segunda más grande (después de Londres) del Imperio Británico . [47]

The decade began with the Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880, held in the large purpose-built Exhibition Building. A telephone exchange was established that year, and the foundations of St Paul's were laid. In 1881, electric light was installed in the Eastern Market, and a generating station capable of supplying 2,000 incandescent lamps was in operation by 1882.[48] The Melbourne cable tramway system opened in 1885 and became one of the world's most extensive systems by 1890.

In 1885, visiting English journalist George Augustus Henry Sala coined the phrase "Marvellous Melbourne", which stuck long into the twentieth century and has come to refer to the opulence and energy of the 1880s,[49] during which time large commercial buildings, grand hotels, banks, coffee palaces, terrace housing and palatial mansions proliferated in the city.[50] The establishment of a hydraulic facility in 1887 allowed for the local manufacture of elevators, resulting in the first construction of high-rise buildings.[51] This period also saw the expansion of a major radial rail-based transport network.[52]

Melbourne's land-boom peaked in 1888,[50] the year it hosted the Centennial Exhibition. A brash boosterism that had typified Melbourne during this time ended in the early 1890s with a severe economic depression, sending the local finance- and property-industries into a period of chaos.[50][53] Sixteen small "land banks" and building societies collapsed, and 133 limited companies went into liquidation. The Melbourne financial crisis was a contributing factor in the Australian economic depression of the 1890s and in the Australian banking crisis of 1893. The effects of the depression on the city were profound, with virtually no new construction until the late 1890s.[54][55]

De facto capital of Australia

At the time of Australia's federation on 1 January 1901 Melbourne became the seat of government of the federated Commonwealth of Australia. The first federal parliament convened on 9 May 1901 in the Royal Exhibition Building, subsequently moving to the Victorian Parliament House, where it sat until it moved to Canberra in 1927. The Governor-General of Australia resided at Government House in Melbourne until 1930, and many major national institutions remained in Melbourne well into the twentieth century.[56][need quotation to verify]

Post-war period

En los años inmediatamente posteriores a la Segunda Guerra Mundial , Melbourne se expandió rápidamente, su crecimiento impulsado por la inmigración de posguerra a Australia , principalmente desde el sur de Europa y el Mediterráneo . [57] Si bien el "Paris End" de Collins Street inició las tiendas boutique de Melbourne y la cultura de los cafés al aire libre , [58] el centro de la ciudad fue visto por muchos como obsoleto, el dominio lúgubre de los trabajadores de oficina, algo expresado por John Brack en su famoso pintando Collins St., 5 pm (1955). [59] Hasta el siglo XXI, Melbourne se consideraba el "corazón industrial" de Australia. [60]

Los límites de altura en el CBD se levantaron en 1958, después de la construcción de ICI House , transformando el horizonte de la ciudad con la introducción de rascacielos. La expansión suburbana luego se intensificó, atendida por nuevos centros comerciales bajo techo comenzando con Chadstone Shopping Center . [61] El período de posguerra también vio una importante renovación del CBD y St Kilda Road que modernizó significativamente la ciudad. [62] Las nuevas regulaciones contra incendios y la remodelación vieron a la mayoría de los edificios más altos del CBD de antes de la guerra demolidos o parcialmente retenidos a través de una política de fachada . Muchas de las mansiones suburbanas más grandes de la era del boom también fueron demolidas o subdivididas.

Para contrarrestar la tendencia hacia el crecimiento residencial suburbano de baja densidad, el gobierno inició una serie de controvertidos proyectos de vivienda pública en el centro de la ciudad por parte de la Comisión de Vivienda de Victoria , que resultó en la demolición de muchos vecindarios y la proliferación de torres de gran altura. [63] En años posteriores, con el rápido aumento de la propiedad de vehículos motorizados, la inversión en el desarrollo de autopistas y autopistas aceleró enormemente la expansión suburbana hacia el exterior y la disminución de la población del centro de la ciudad. El gobierno de Bolte buscó acelerar rápidamente la modernización de Melbourne. Proyectos de carreteras importantes, incluida la remodelación de St Kilda Junction , el ensanchamiento de Hoddle Street y luego la extensaEl Plan de Transporte de Melbourne de 1969 cambió la faz de la ciudad en un entorno dominado por los automóviles. [64]

Los auges financieros y mineros de Australia durante 1969 y 1970 dieron como resultado el establecimiento de la sede de muchas empresas importantes ( BHP y Rio Tinto , entre otras) en la ciudad. La entonces floreciente economía de Nauru resultó en varias inversiones ambiciosas en Melbourne, como Nauru House . [65] Melbourne siguió siendo el principal centro comercial y financiero de Australia hasta finales de la década de 1970, cuando comenzó a perder esta primacía frente a Sydney. [66]

Melbourne experienced an economic downturn between 1989 and 1992, following the collapse of several local financial institutions. In 1992, the newly elected Kennett government began a campaign to revive the economy with an aggressive development campaign of public works coupled with the promotion of the city as a tourist destination with a focus on major events and sports tourism.[67] During this period the Australian Grand Prix moved to Melbourne from Adelaide. Major projects included the construction of a new facility for the Melbourne Museum, Federation Square, the Melbourne Convention & Exhibition Centre, Crown Casino and the Autopista de peaje CityLink . Otras estrategias incluyeron la privatización de algunos de los servicios de Melbourne, incluida la energía y el transporte público, y una reducción de la financiación de servicios públicos como la salud, la educación y la infraestructura de transporte público. [68]

Melbourne contemporánea

Desde mediados de la década de 1990, Melbourne ha mantenido un crecimiento significativo de la población y el empleo. Ha habido una inversión internacional sustancial en las industrias y el mercado inmobiliario de la ciudad. Se ha producido una importante renovación urbana del centro de la ciudad en áreas como Southbank , Port Melbourne , Melbourne Docklands y, más recientemente, South Wharf . Melbourne registró el aumento de población y la tasa de crecimiento económico más altos de todas las ciudades capitales de Australia entre 2001 y 2004. [69]

A partir de 2006, el crecimiento de la ciudad se extendió a "cuñas verdes" y más allá del límite de crecimiento urbano de la ciudad . Las predicciones de que la población de la ciudad llegaría a los 5 millones de personas empujaron al gobierno estatal a revisar el límite de crecimiento en 2008 como parte de su estrategia Melbourne @ Five Million. [70] En 2009, Melbourne se vio menos afectada por la crisis financiera de finales de la década de 2000 en comparación con otras ciudades australianas. En ese momento, se crearon más puestos de trabajo nuevos en Melbourne que en cualquier otra ciudad australiana, casi tantos como las siguientes dos ciudades de más rápido crecimiento, Brisbane y Perth, combinadas, [71] y el mercado inmobiliario de Melbourne siguió siendo muy caro, [72] lo que resultó en precios de la propiedad históricamente altos y aumentos generalizados de los alquileres.[73] En 2020, Melbourne fue clasificada como una ciudad Alfa por la Globalization and World Cities Research Network . [74] De todas las principales ciudades australianas, Melbourne ha sido la más afectada por la pandemia de COVID-19 y ha soportado la mayor cantidad de días de restricciones de cierre fuera de cualquier ciudad del mundo. [75]

Geografía

Esta sección necesita citas adicionales para su verificación . ( Agosto de 2018 ) |

Melbourne is in the southeastern part of mainland Australia, within the state of Victoria. Geologically, it is built on the confluence of Quaternary lava flows to the west, Silurian mudstones to the east, and Holocene sand accumulation to the southeast along Port Phillip. The southeastern suburbs are situated on the Selwyn fault which transects Mount Martha and Cranbourne.[76]

Melbourne se extiende a lo largo del río Yarra hacia el valle de Yarra y los rangos de Dandenong al este. Se extiende hacia el norte a través de los ondulados valles de matorrales de los afluentes del Yarra: Moonee Ponds Creek (hacia el aeropuerto de Tullamarine), Merri Creek , Darebin Creek y Plenty River, hasta los corredores de crecimiento suburbanos exteriores de Craigieburn y Whittlesea .

La ciudad llega al sureste a través de Dandenong hasta el corredor de crecimiento de Pakenham hacia West Gippsland , y hacia el sur a través del valle de Dandenong Creek y la ciudad de Frankston . En el oeste, se extiende a lo largo del río Maribyrnong y sus afluentes hacia el norte hacia Sunbury y las estribaciones de la cordillera de Macedonia , y a lo largo de la llanura volcánica plana hacia Melton en el oeste, Werribee en las estribaciones de la cresta de granito You Yangs al suroeste de el CBD. El pequeño río, and the township of the same name, marks the border between Melbourne and neighbouring Geelong city.

Melbourne's major bayside beaches are in the various suburbs along the shores of Port Phillip Bay, in areas like Port Melbourne, Albert Park, St Kilda, Elwood, Brighton, Sandringham, Mentone, Frankston, Altona, Williamstown and Werribee South. The nearest surf beaches are 85 kilometres (53 mi) south of the Melbourne CBD in the back-beaches of Rye, Sorrento and Portsea.[77][78]

Climate

Melbourne tiene un clima oceánico templado ( clasificación climática de Köppen Cfb ), que limita con un clima subtropical húmedo ( clasificación climática de Köppen Cfa ), con veranos cálidos a calurosos e inviernos suaves. [79] [80] Melbourne es bien conocida por sus condiciones climáticas cambiantes , principalmente debido a que se encuentra en el límite de las zonas cálidas del interior y el frío océano del sur. Esta diferencia de temperatura es más pronunciada en los meses de primavera y verano y puede provocar la formación de fuertes frentes fríos . Estos frentes fríos pueden ser responsables de diversas formas de clima severo, desde vendavales hasta tormentas eléctricas.y granizo , grandes descensos de temperatura y fuertes lluvias. Los inviernos, sin embargo, suelen ser muy estables, pero bastante húmedos y, a menudo, nublados.

Port Phillip es a menudo más cálido que los océanos circundantes y / o la masa terrestre, particularmente en primavera y otoño; esto puede crear un "efecto bahía", similar al " efecto lago " observado en climas más fríos, donde los chubascos se intensifican a sotavento de la bahía. Los arroyos relativamente estrechos de fuertes lluvias a menudo pueden afectar los mismos lugares (generalmente los suburbios del este) durante un período prolongado, mientras que el resto de Melbourne y sus alrededores permanecen secos. En general, debido a la sombra de lluvia de Otway Ranges , Melbourne es, sin embargo, más seca que el promedio del sur de Victoria. Dentro de la ciudad y sus alrededores, las precipitaciones varían ampliamente, desde alrededor de 425 milímetros (17 pulgadas) en Little River hasta 1.250 milímetros (49 pulgadas) en la franja oriental enGembrook . Melbourne recibe 48,6 días despejados al año. Las temperaturas del punto de rocío en el verano oscilan entre 9,5 y 11,7 ° C (49,1 a 53,1 ° F). [81]

Melbourne is also prone to isolated convective showers forming when a cold pool crosses the state, especially if there is considerable daytime heating. These showers are often heavy and can include hail, squalls, and significant drops in temperature, but they often pass through very quickly with a rapid clearing trend to sunny and relatively calm weather and the temperature rising back to what it was before the shower. This can occur in the space of minutes and can be repeated many times a day, giving Melbourne a reputation for having "four seasons in one day",[82] a phrase that is part of local popular culture.[83] The lowest temperature on record is −2.8 °C (27.0 °F), on 21 July 1869.[84]La temperatura más alta registrada en la ciudad de Melbourne fue de 46,4 ° C (115,5 ° F), el 7 de febrero de 2009 . [85] Si bien ocasionalmente se ve nieve en elevaciones más altas en las afueras de la ciudad, no se ha registrado en el Distrito Central de Negocios desde 1986. [86]

La temperatura media del mar varía de 14,6 ° C (58,3 ° F) en septiembre a 18,8 ° C (65,8 ° F) en febrero; [87] en Port Melbourne , el rango medio de temperatura del mar es el mismo. [88]

| Datos climáticos de la oficina regional de Melbourne (1991-2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mes | ene | feb | mar | abr | Mayo | jun | jul | ago | sep | oct | nov | dic | Año |

| Registro alto ° C (° F) | 45,6 (114,1) | 46,4 (115,5) | 41,7 (107,1) | 34,9 (94,8) | 28,7 (83,7) | 22,4 (72,3) | 23,3 (73,9) | 26,5 (79,7) | 31,4 (88,5) | 36,9 (98,4) | 40,9 (105,6) | 43,7 (110,7) | 46,4 (115,5) |

| Promedio alto ° C (° F) | 27,0 (80,6) | 26,9 (80,4) | 24,6 (76,3) | 21,1 (70,0) | 17,6 (63,7) | 15,1 (59,2) | 14,5 (58,1) | 15,9 (60,6) | 18,1 (64,6) | 20,5 (68,9) | 22,9 (73,2) | 24,8 (76,6) | 20,8 (69,4) |

| Media diaria ° C (° F) | 21,6 (70,9) | 21,7 (71,1) | 19,6 (67,3) | 16,5 (61,7) | 13,7 (56,7) | 11,7 (53,1) | 11,0 (51,8) | 11,9 (53,4) | 13,8 (56,8) | 15,7 (60,3) | 17,9 (64,2) | 19,6 (67,3) | 16,2 (61,2) |

| Promedio bajo ° C (° F) | 16,1 (61,0) | 16,4 (61,5) | 14,6 (58,3) | 11,8 (53,2) | 9,8 (49,6) | 8,2 (46,8) | 7,5 (45,5) | 7,9 (46,2) | 9,4 (48,9) | 10,9 (51,6) | 12,8 (55,0) | 14,3 (57,7) | 11,6 (52,9) |

| Registro bajo ° C (° F) | 5,5 (41,9) | 4,5 (40,1) | 2,8 (37,0) | 1,5 (34,7) | −1,1 (30,0) | −2,2 (28,0) | −2,8 (27,0) | −2,1 (28,2) | −0,5 (31,1) | 0,1 (32,2) | 2,5 (36,5) | 4,4 (39,9) | −2,8 (27,0) |

| Precipitación media mm (pulgadas) | 44,2 (1,74) | 50,2 (1,98) | 39,0 (1,54) | 53,2 (2,09) | 43,9 (1,73) | 49,5 (1,95) | 39,8 (1,57) | 47,0 (1,85) | 54,5 (2,15) | 55,8 (2,20) | 63,3 (2,49) | 60,9 (2,40) | 600,9 (23,66) |

| Días lluviosos promedio (≥ 1 mm) | 5,6 | 5,0 | 5.5 | 7.1 | 8.1 | 8,6 | 8.3 | 9.4 | 9,8 | 9.0 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 90,6 |

| Humedad relativa media de la tarde (%) | 47 | 47 | 47 | 50 | 57 | 61 | 59 | 53 | 50 | 47 | 47 | 46 | 51 |

| Promedio de horas de sol mensuales | 272,8 | 228,8 | 226,3 | 186,0 | 142,6 | 123,0 | 136,4 | 167,4 | 186,0 | 226,3 | 225,0 | 263,5 | 2.384,1 |

| Fuente 1: Oficina de Meteorología . [89] [90] [91] | |||||||||||||

| Fuente 2: Oficina de Meteorología , Aeropuerto de Melbourne (horas de sol) [92] | |||||||||||||

Estructura urbana

Melbourne's urban area is approximately 2,453 km2, slightly larger than that of London and Mexico City,[93] while its metropolitan area is 9,993 km2 (3,858 sq mi)–larger than Jakarta (at 7,063 km2), but smaller than New York City (at 11,875 km2). The Hoddle Grid, a grid of streets measuring approximately 1 by 1⁄2 mile (1.61 by 0.80 km), forms the nucleus of Melbourne's central business district(CBD). El borde sur de la cuadrícula da al río Yarra. Desarrollos de oficinas, comerciales y públicos más recientes en los distritos contiguos de Southbank y Docklands han convertido estas áreas en extensiones del CBD en todo menos en el nombre. Un subproducto del diseño del CBD es su red de carriles y salas de juegos , como Block Arcade y Royal Arcade . [94] [95]

Melbourne has become Australia's most densely populated area, with approximately 19,500 residents per square kilometre,[96] and is home to more skyscrapers than any other Australian city, the tallest being Australia 108, situated in Southbank. [97] Melbourne's newest planned skyscraper, Southbank By Beulah[98] (also known as "Green Spine"), has recently been approved for construction and will be the tallest structure in Australia by 2025.

The CBD and surrounds also contain many significant historic buildings such as the Royal Exhibition Building, the Melbourne Town Hall and Parliament House.[99][100]Although the area is described as the centre, it is not actually the demographic centre of Melbourne at all, due to an urban sprawl to the south east, the demographic centre being located at Glen Iris.[101]Melbourne is typical of Australian capital cities in that after the turn of the 20th century, it expanded with the underlying notion of a 'quarter acre home and garden' for every family, often referred to locally as the Australian Dream.[102][103] This, coupled with the popularity of the private automobile after 1945, led to the auto-centric urban structure now present today in the middle and outer suburbs. Much of metropolitan Melbourne is accordingly characterised by low-density sprawl, whilst its inner-city areas feature predominantly medium-density, transit-oriented urban forms. The city centre, Docklands, St. Kilda Road and Southbank areas feature high-density forms.

Melbourne is often referred to as Australia's garden city, and the state of Victoria was once known as the garden state.[104][105][106] There is an abundance of parks and gardens in Melbourne,[107] many close to the CBD with a variety of common and rare plant species amid landscaped vistas, pedestrian pathways and tree-lined avenues. Melbourne's parks are often considered the best public parks in all of Australia's major cities.[108] There are also many parks in the surrounding suburbs of Melbourne, such as in the municipalities of Stonnington, Boroondara and Port Phillip, south east of the central business district. Several national parks have been designated around the urban area of Melbourne, including the Mornington Peninsula National Park, Port Phillip Heads Marine National Park and Point Nepean National Park in the southeast, Organ Pipes National Park to the north and Dandenong Ranges National Park to the east. There are also a number of significant state parks just outside Melbourne.[109][110] The extensive area covered by urban Melbourne is formally divided into hundreds of suburbs (for addressing and postal purposes), and administered as local government areas[111]31 de las cuales están ubicadas dentro del área metropolitana. [112]

Alojamiento

Melbourne tiene viviendas públicas mínimas y una gran demanda de viviendas de alquiler, lo que se está volviendo inasequible para algunos. [113] [114] [115] La vivienda pública es administrada y proporcionada por el Departamento de Familias, Equidad y Vivienda del gobierno de Victoria , y opera dentro del marco del Acuerdo de Vivienda Commonwealth-State, por el cual los gobiernos federal y estatal proporcionan fondos para alojamiento.

Melbourne está experimentando un alto crecimiento demográfico, lo que genera una gran demanda de viviendas. Este boom inmobiliario ha incrementado el precio de la vivienda y los alquileres, así como la disponibilidad de todo tipo de vivienda. La subdivisión ocurre regularmente en las áreas exteriores de Melbourne, con numerosos desarrolladores que ofrecen paquetes de casas y terrenos. Sin embargo, desde el lanzamiento de Melbourne 2030 en 2002, las políticas de planificación han alentado el desarrollo de densidad media y alta en áreas existentes con buen acceso al transporte público y otros servicios. Como resultado de esto, los suburbios del anillo central y exterior de Melbourne han visto una importante remodelación de zonas industriales abandonadas . [116]

Arquitectura

On the back of the 1850s gold rush and 1880s land boom, Melbourne became renowned as one of the world's great Victorian-era cities, a reputation that persists due to its diverse range of Victorian architecture.[117] High concentrations of well-preserved Victorian-era buildings can be found in the inner suburbs, such as Carlton, East Melbourne and South Melbourne.[118] Outstanding examples of Melbourne's built Victorian heritage include the World Heritage-listed Royal Exhibition Building (1880), the General Post Office (1867), Hotel Windsor (1884) and the Block Arcade (1891).[119] Comparatively little remains of Melbourne's pre-gold rush architecture; St James Old Cathedral (1839) and St Francis' Church (1845) are among the few examples left in the CBD. Many of the CBD's Victorian boom-time landmarks were also demolished in the decades after World War II, including the Federal Coffee Palace (1888) and the APA Building (1889), one of the tallest early skyscrapers upon completion.[120][121] Heritage listings and heritage overlays have since been introduced in an effort to prevent further losses of the city's historic fabric.

En consonancia con la expansión de la ciudad a principios del siglo XX, los suburbios como Hawthorn y Camberwell se definen en gran medida por los estilos arquitectónicos de la Federación y el estilo eduardiano . Los baños de la ciudad , construidos en 1903, son un ejemplo destacado de este último estilo en el CBD. El edificio Nicholas de 1926 es el ejemplo más grandioso de la ciudad del estilo de la escuela de Chicago , mientras que la influencia del Art Deco es evidente en el Manchester Unity Building , terminado en 1932.

The city also features the Shrine of Remembrance, which was built as a memorial to the men and women of Victoria who served in World War I and is now a memorial to all Australians who have served in war.

Residential architecture is not defined by a single architectural style, but rather an eclectic mix of large McMansion-style houses (particularly in areas of urban sprawl), apartment buildings, condominiums, and townhouses which generally characterise the medium-density inner-city neighbourhoods. Freestanding dwellings with relatively large gardens are perhaps the most common type of housing outside inner city Melbourne. Victorian terrace housing, townhouses and historic Italianate, Tudor revival and Neo-Georgian mansions are all common in inner-city neighbourhoods such as Carlton, Fitzroy and further into suburban enclaves like Toorak.[citation needed]

Culture

Often referred to as Australia's cultural capital, Melbourne is recognised globally as a centre of sport, music, theatre, comedy, art, literature, film and television.[122] For much of the 2010s, it held the top position in The Economist Intelligence Unit's list of the world's most liveable cities, partly due to its cultural attributes.[20]

The city celebrates a wide variety of annual cultural events and festivals of all types, including the Melbourne International Arts Festival, Melbourne International Comedy Festival, Melbourne Fringe Festival and Moomba, Australia's largest free community festival.

The State Library of Victoria, founded in 1854, is one of the world's oldest free public libraries and, as of 2018, the fourth most-visited library globally.[123] Between the gold rush and the crash of 1890, Melbourne was Australia's literary capital, famously referred to by Henry Kendall as "that wild bleak Bohemia south of the Murray".[124] At this time, Melbourne-based writers and poets Marcus Clarke, Adam Lindsay Gordon and Rolf Boldrewood produced classic visions of colonial life. Fergus Hume's The Mystery of a Hansom Cab (1886), the fastest-selling crime novel of the era, is set in Melbourne, as is Australia's best-selling book of poetry, C. J. Dennis' The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke (1915).[125] Contemporary Melbourne authors who have written award-winning books set in the city include Peter Carey, Helen Garner and Christos Tsiolkas. Melbourne has Australia's widest range of bookstores, as well as the nation's largest publishing sector.[126] The city is also home to the Melbourne Writers Festival and hosts the Victorian Premier's Literary Awards. In 2008, it became the second city to be named a UNESCO Ciudad de la Literatura .

Ray Lawler's play Summer of the Seventeenth Doll is set in Carlton and debuted in 1955, the same year that Edna Everage, Barry Humphries' Moonee Ponds housewife character, first appeared on stage, both sparking international interest in Australian theatre. Melbourne's East End Theatre District is known for its Victorian era theatres, such as the Athenaeum, Her Majesty's and the Princess, as well as the Forum and the Regent. Other heritage-listed theatres include the art deco landmarks The Capitol and St Kilda's Palais Theatre , el teatro sentado más grande de Australia con una capacidad para 3.000 personas. [127] El Arts Precinct en Southbank alberga el Arts Centre Melbourne (que incluye el State Theatre y Hamer Hall ), así como el Melbourne Recital Centre y Southbank Theatre , hogar de Melbourne Theatre Company , la compañía de teatro profesional más antigua de Australia. [128] El Ballet de Australia , la Ópera de Australia y la Orquesta Sinfónica de Melbourne también tienen su sede en el recinto.

Melbourne has been called "the live music capital of the world";[129] one study found it has more music venues per capita than any other world city sampled, with 17.5 million patron visits to 553 venues in 2016.[129][130] The Sidney Myer Music Bowl in Kings Domain hosted the largest crowd ever for a music concert in Australia when an estimated 200,000 attendees saw Melbourne band The Seekers in 1967.[131] Airing between 1974 and 1987, Melbourne's Countdown helped launch the careers of Crowded House, Men at Work and Kylie Minogue, among other local acts. Several distinct post-punk scenes flourished in Melbourne during the late 1970s, including the Fitzroy-based Little Band scene and the St Kilda scene centered at the Crystal Ballroom, which gave rise to Dead Can Dance and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, respectively.[132] More recent independent acts from Melbourne to achieve global recognition include The Avalanches, Gotye and King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard. Melbourne is also regarded as a centre of EDM, and lends its name to the El género Melbourne Bounce y el estilo de baile Melbourne Shuffle , ambos surgieron de la escena rave underground de la ciudad . [133]

Establecida en 1861, la Galería Nacional de Victoria es el museo de arte más grande y antiguo de Australia. Varios movimientos artísticos se originaron en Melbourne, el más famoso es la Escuela de impresionistas de Heidelberg , que lleva el nombre de un suburbio donde acamparon para pintar al aire libre en la década de 1880. [134] Le siguieron los tonalistas australianos , [135] algunos de los cuales fundaron Montsalvat , la colonia de arte más antigua de Australia. Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, los Angry Penguins , un grupo de artistas de vanguardia, se reunieron en una granja lechera de Bulleen , ahora Museo Heide de Arte Moderno.. The city is also home to the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art. In the 2000s, Melbourne street art became globally renowned and a major tourist drawcard, with "laneway galleries" such as Hosier Lane attracting more Instagram hashtags than some of the city's traditional attractions, such as the Melbourne Zoo.[136][137]

Un cuarto de siglo después de la ejecución del bushranger Ned Kelly en Old Melbourne Gaol , The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), producida en Melbourne , el primer largometraje narrativo del mundo , se estrenó en el Athenaeum antes mencionado, impulsando la primera película cinematográfica de Australia. auge. [138] Melbourne siguió siendo un líder mundial en la realización de películas hasta mediados de la década de 1910, cuando varios factores, incluida la prohibición de las películas de bushranger , contribuyeron a un declive de la industria durante décadas. [138] Una película notable filmada y ambientada en Melbourne durante esta pausa fue On the Beach (1959). [139] Los cineastas de Melbourne lideraron laAustralian Film Revival with ocker comedies such as Stork (1971) and Alvin Purple (1973).[140] Other films shot and set in Melbourne include Mad Max (1979), Romper Stomper (1992), Chopper (2000) and Animal Kingdom (2010). The Melbourne International Film Festival began in 1952 and is one of the world's oldest film festivals. The AACTA Awards, Australia's top screen awards, were inaugurated by the festival in 1958. Melbourne is also home to Docklands Studios Melbourne (the city's largest film and television studio complex),[141] the Australian Centre for the Moving Image and the headquarters of Village Roadshow Pictures, Australia's largest film production company.

Sports

Melbourne has long been regarded as Australia's sporting capital due to the role it has played in the development of Australian sport, the range and quality of its sporting events and venues, and its high rates of spectatorship and participation.[142] The city is also home to 27 professional sports teams competing at the national level, the most of any Australian city. Melbourne's sporting reputation was recognised in 2016 when, after being ranked as the world's top sports city three times biennially, the Ultimate Sports City Awards in Switzerland named it 'Sports City of the Decade'.[143]

La ciudad ha sido sede de una serie de importantes eventos deportivos internacionales, entre los que destaca los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano de 1956 , los primeros Juegos Olímpicos celebrados fuera de Europa y Estados Unidos. [144] Melbourne también fue sede de los Juegos de la Commonwealth de 2006 y es el hogar de varios eventos internacionales anuales importantes, incluido el Abierto de Australia , el primero de los cuatro torneos de tenis Grand Slam . Celebrada por primera vez en 1861 y declarada día festivo para todos los habitantes de Melbourne en 1873, la Copa de Melbourne es la carrera de caballos para discapacitados más rica del mundo y se la conoce como "la carrera que detiene a una nación". El Gran Premio de Australia de Fórmula Uno se ha celebrado en elCircuito Albert Park desde 1996.

Cricket was one of the first sports to become organised in Melbourne with the Melbourne Cricket Club forming within three years of settlement. The club manages one of the world's largest stadiums, the 100,000 capacity Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG).[145] Established in 1853, the MCG is notable for hosting the first Test match and the first One Day International, played between Australia and England in 1877 and 1971, respectively. It is also the home of the National Sports Museum,[146] and serves as the home ground of the Victoria cricket team. At Twenty20 level, the Melbourne Stars and Melbourne Renegades compete in the Big Bash League.

El fútbol de reglas australiano , el deporte para espectadores más popular de Australia, tiene sus orígenes en partidos jugados en parques junto al MCG en 1858. Sus primeras leyes fueron codificadas al año siguiente por el Melbourne Football Club , [147] también miembro fundador, en 1896. de la Liga Australiana de Fútbol (AFL), la competición profesional de élite de este deporte. Con sede en el Docklands Stadium , la AFL cuenta con otros ocho clubes con sede en Melbourne: Carlton , Collingwood , Essendon , Hawthorn , North Melbourne , Richmond ,St Kilda y los Bulldogs occidentales . [148] La ciudad alberga hasta cinco partidos de la AFL por ronda durante la temporada en casa y fuera de casa, atrayendo un promedio de 40.000 espectadores por partido. [149] La Gran Final de la AFL , tradicionalmente celebrada en el MCG, es el evento de campeonato de clubes con mayor asistencia en el mundo .

En fútbol , Melbourne está representada en la A-League por Melbourne Victory , Melbourne City FC y Western United FC . El equipo de la liga de rugby Melbourne Storm juega en la National Rugby League , y en el rugby union , Melbourne Rebels y Melbourne Rising compiten en las competencias de Super Rugby y National Rugby Championship , respectivamente. Los deportes norteamericanos también han ganado popularidad en Melbourne: equipos de baloncesto South East Melbourne Phoenix y Melbourne United play in the NBL; Melbourne Ice and Melbourne Mustangs play in the Australian Ice Hockey League; and Melbourne Aces plays in the Australian Baseball League. Rowing also forms part of Melbourne's sporting identity, with a number of clubs located on the Yarra River, out of which many Australian Olympians trained.

Economy

Melbourne tiene una economía altamente diversificada con fortalezas particulares en finanzas, manufactura, investigación, TI, educación, logística, transporte y turismo. Melbourne alberga la sede de muchas de las corporaciones más grandes de Australia, incluidas cinco de las diez más grandes del país (según los ingresos) y cinco de las siete más grandes del país (según la capitalización de mercado ) [150] ( ANZ , BHP Billiton ( la empresa minera más grande del mundo), el National Australia Bank , CSL y Telstra , así como organismos representativos y grupos de expertos como el Business Council of Australia y elAustralian Council of Trade Unions. Melbourne's suburbs also have the head offices of Coles Group (owner of Coles Supermarkets) and Wesfarmers companies Bunnings, Target, K-Mart and Officeworks. The city is home to Australia's second busiest seaport, after Port Botany in Sydney.[151] Melbourne Airport provides an entry point for national and international visitors, and is Australia's second busiest airport.[152]

Melbourne is also an important financial centre. In the 2018 Global Financial Centres Index, Melbourne was ranked as having the 15th most competitive financial centre in the world.[153] Two of the big four banks, NAB and ANZ, are headquartered in Melbourne. The city has carved out a niche as Australia's leading centre for superannuation (pension) funds, with 40% of the total, and 65% of industry super-funds including the AU$109 billion-dollar Federal Government Future Fund. The city was rated 41st within the top 50 financial cities as surveyed by the MasterCard Worldwide Centers of Commerce Index (2008),[154] second only to Sydney (12th) in Australia. Melbourne is Australia's second-largest industrial centre.[155]

It is the Australian base for a number of significant manufacturers including Boeing, truck-makers Kenworth and Iveco, Cadbury as well as Bombardier Transportation and Jayco, among many others. It is also home to a wide variety of other manufacturers, ranging from petrochemicals and pharmaceuticals to fashion garments, paper manufacturing and food processing.[157] The south-eastern suburb of Scoresby is home to Nintendo's Australian headquarters. The city also has a research and development hub for Ford Australia, as well as a global design studio and technical centre for General Motors and Toyota respectively.

CSL, one of the world's top five biotech companies, and Sigma Pharmaceuticals have their headquarters in Melbourne. The two are the largest listed Australian pharmaceutical companies.[158] Melbourne has an important ICT industry that employs over 60,000 people (one third of Australia's ICT workforce), with a turnover of AU$19.8 billion and export revenues of AU615 million. In addition, tourism also plays an important role in Melbourne's economy, with about 7.6 million domestic visitors and 1.88 million international visitors in 2004.[159]Melbourne ha atraído una participación cada vez mayor de los mercados de conferencias nacionales e internacionales. La construcción comenzó en febrero de 2006 de un centro de convenciones internacional de 5000 millones de dólares australianos, un hotel Hilton y un recinto comercial adyacente al Centro de Convenciones y Exposiciones de Melbourne para vincular el desarrollo a lo largo del río Yarra con el recinto de Southbank y la remodelación multimillonaria de Docklands . [160]

The Economist Intelligence Unit clasifica a Melbourne como la cuarta ciudad más cara del mundo para vivir de acuerdo con su índice mundial del costo de vida en 2013. [161]

Turismo

Melbourne is the second most visited city in Australia and the seventy-third most visited city in the world.[162] In 2018, 10.8 million domestic overnight tourists and 2.9 million international overnight tourists visited Melbourne.[163] The most visited attractions are: Federation Square, Queen Victoria Market, Crown Casino, Southbank, Melbourne Zoo, Melbourne Aquarium, Docklands, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Museum, Melbourne Observation Deck, Arts Centre Melbourne, and the Melbourne Cricket Ground.[164] Luna Park, a theme park modelled on New York's Coney Island and Seattle's Luna Park,[165] is also a popular destination for visitors.[166] In its annual survey of readers, the Condé Nast Traveler magazine found that both Melbourne and Auckland were considered the world's friendliest cities in 2014. The magazine highlighted the connection the city inhabitants have to public art and the many parks across the city.[167][168] Its high liveability rankings make it one of the safest world cities for travellers.[169][170]

Demographics

En 2018, la población del área metropolitana de Melbourne era 4.963.349. [171]

Aunque la migración interestatal neta de Victoria ha fluctuado, la población de la división estadística de Melbourne ha crecido en unas 70.000 personas al año desde 2005. Melbourne ha atraído ahora la mayor proporción de inmigrantes internacionales en el extranjero (48.000) y ha superado en porcentaje a la entrada de inmigrantes internacionales de Sydney. además de tener una fuerte migración interestatal desde Sydney y otras capitales debido a viviendas más asequibles y costo de vida. [172]

In recent years, Melton, Wyndham and Casey, part of the Melbourne statistical division, have recorded the highest growth rate of all local government areas in Australia. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic,[173] Melbourne was on track to overtake Sydney in population by 2028.[174] The ABS has projected in two scenarios that Sydney will remain larger than Melbourne beyond 2056, albeit by a margin of less than 3% compared to a margin of 12% today.

After a trend of declining population density since World War II, the city has seen increased density in the inner and western suburbs, aided in part by Victorian Government planning, such as Postcode 3000 and Melbourne 2030, which have aimed to curtail urban sprawl.[175][176] As of 2018, the CBD is the most densely populated area in Australia with more than 19,000 residents per square kilometre, and the inner city suburbs of Carlton, South Yarra, Fitzroy and Collingwood make up Victoria's top five.[177]

Ancestry and immigration

| Birthplace[N 1] | Population |

|---|---|

| Australia | 2,684,072 |

| India | 161,078 |

| Mainland China | 155,998 |

| England | 133,300 |

| Vietnam | 79,054 |

| New Zealand | 78,906 |

| Italy | 63,332 |

| Sri Lanka | 54,030 |

| Malaysia | 47,642 |

| Greece | 45,618 |

| Philippines | 45,157 |

| South Africa | 24,168 |

| Hong Kong | 20,840 |

At the 2016 census, the most commonly nominated ancestries were:[N 2][178]

- English (28%)

- Australian (26%)[N 3]

- Irish (9.7%)

- Chinese (8.5%)

- Scottish (7.8%)

- Italian (7.1%)

- Indian (4.7%)

- Greek (3.9%)

- German (3.2%)

- Vietnamese (2.4%)

- Dutch (1.6%)

- Maltese (1.6%)

- Filipino (1.4%)

- Sri Lankan (1.3%)

- Polish (1.1%)

- Lebanese (1.1%)

0.5% of the population, or 24,062 people, identified as Indigenous Australians (Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders) in 2016.[N 4][178]

Melbourne has the 10th largest immigrant population among world metropolitan areas. In Greater Melbourne at the 2016 census, 63.3% of residents were born in Australia. The other most common countries of birth were India (3.6%), Mainland China (3.5%), England (3%), Vietnam (1.8%) and New Zealand (1.8%).[180]

Language

As of the 2016 census, 62% of Melburnians speak only English at home.[180] Mandarin (4.1%), Greek (2.4%), Italian (2.3%), Vietnamese (2.3%), and Cantonese (1.7%) were the most common foreign languages spoken at home by residents of Melbourne as of 2016.[180]

Religion

Melbourne has a wide range of religious faiths, the most widely held of which is Christianity. This is signified by the city's two large cathedrals—St Patrick's (Roman Catholic), and St Paul's (Anglican). Both were built in the Victorian era and are of considerable heritage significance as major landmarks of the city.[181] In recent years, Greater Melbourne's irreligious community has grown to be one of the largest in Australia.[182]

According to the 2016 Census, the largest responses on religious belief in Melbourne were no religion (31.9%), Catholic (23.4%), none stated (9.1%), Anglican (7.6%), Eastern Orthodox (4.3%), Islam (4.2%), Buddhism (3.8%), Hinduism (2.9%), Uniting Church (2.3%), Presbyterian and Reformed (1.6%), Baptist (1.3%), Sikhism (1.2%) and Judaism (0.9%).[183]

Over 180,000 Muslims live in Melbourne.[183] Muslim religious life in Melbourne is centred on more than 25 mosques and a large number of prayer rooms at university campuses, workplaces and other venues.[184]

As of 2000[update], Melbourne had the largest population of Polish Jews in Australia. The city was also home to the largest number of Holocaust survivors of any Australian city,[185] indeed the highest per capita outside Israel itself.[186] Reflecting this vibrant community, Melbourne has a plethora of Jewish cultural, religious and educational institutions, including over 40 synagogues and 7 full-time parochial day schools,[187] along with a local Jewish newspaper.[188]

Education

Some of Australia's most prominent and well-known schools are based in Melbourne. Of the top twenty high schools in Australia according to the My Choice Schools Ranking, five are in Melbourne.[189] There has also been a rapid increase in the number of International students studying in the city. Furthermore, Melbourne was ranked the world's fourth top university city in 2008 after London, Boston and Tokyo in a poll commissioned by the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology.[190] Eight public universities operate in Melbourne: the University of Melbourne, Monash University, Swinburne University of Technology, Deakin University, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT University), La Trobe University, Australian Catholic University (ACU) and Victoria University (VU).

Las universidades de Melbourne tienen campus en toda Australia y algunas a nivel internacional. La Universidad Swinburne y la Universidad Monash tienen campus en Malasia , mientras que Monash tiene un centro de investigación con sede en Prato, Italia . La Universidad de Melbourne, la segunda universidad más antigua de Australia, [191] ocupó el primer lugar entre las universidades australianas en el ranking internacional THES de 2016 . En 2018 Times Higher Education Supplement clasificó a la Universidad de Melbourne como la 32ª mejor universidad del mundo, que es más alta que las clasificaciones en 2016 y 2017, [192] La Universidad de Monash ocupó el 80º lugar mejor. [193] Ambos son miembros del Grupo de los Ocho., una coalición de instituciones de educación superior australianas líderes que ofrecen educación integral y líder. [194]

As of 2017 RMIT University is ranked 17th in the world in art & design, and 28th in architecture.[195] The Swinburne University of Technology, based in the inner-city Melbourne suburb of Hawthorn, was as of 2014 ranked 76th–100th in the world for physics by the Academic Ranking of World Universities.[196] Deakin University maintains two major campuses in Melbourne and Geelong, and is the third largest university in Victoria. In recent years, the number of international students at Melbourne's universities has risen rapidly, a result of an increasing number of places being made available for them.[197] Education in Melbourne is overseen by the Victorian Department of Education (DET), whose role is to 'provide policy and planning advice for the delivery of education'.[198]

Media

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

Melbourne is served by thirty digital free-to-air television channels:

- ABC

- ABC HD (ABC broadcast in HD)

- ABC TV Plus/KIDS

- ABC ME

- ABC News

- SBS

- SBS HD (SBS broadcast in HD)

- SBS Viceland

- SBS Viceland HD (SBS Viceland broadcast in HD)

- SBS Food

- SBS World Movies

- NITV

- Seven

- 7HD (Seven broadcast in HD)

- 7Two

- 7mate

- 7mate HD

- 7flix

- Racing.com

- openshop

- Nine

- 9HD (Nine broadcast in HD)

- 9Gem

- 9Go!

- 9Life

- 9Rush

- 10

- 10 HD (10 broadcast in HD)

- 10 Bold

- 10 Peach

- 10 Shake

- TVSN

- Spree TV

- C31 Melbourne (Melbourne's community TV station)

Hay tres periódicos que sirven a Melbourne: el Herald Sun (tabloide), The Age (compacto) y The Australian (sábana nacional). Seis estaciones de televisión en abierto dan servicio a Greater Melbourne y Geelong: ABC Victoria, ( ABV ), SBS Victoria (SBS), Seven Melbourne ( HSV ), Nine Melbourne ( GTV ), Ten Melbourne ( ATV ), C31 Melbourne (MGV) - Televisión comunitaria. Cada estación (excepto C31) transmite un canal principal y varios canales múltiples. C31 solo se emite desde los transmisores enMonte Dandenong y South Yarra . Compañías híbridas de medios digitales / impresos como Broadsheet y ThreeThousand tienen su sede y prestan servicios principalmente en Melbourne.

A long list of AM and FM radio stations broadcast to greater Melbourne. These include "public" (i.e., state-owned ABC and SBS) and community stations. Many commercial stations are networked-owned: Nova Entertainment has Nova 100 and Smooth; ARN controls Gold 104.3 and KIIS 101.1; and Southern Cross Austereo runs both Fox and Triple M. Stations from towns in regional Victoria may also be heard (e.g. 93.9 Bay FM, Geelong). Youth alternatives include ABC Triple J and youth run SYN. Triple J, and similarly PBS and Triple R, strive to play under represented music. JOY 94.9 caters for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender audiences. For fans of classical music there are 3MBS and ABC Classic FM. Light FM is a contemporary Christian station. AM stations include ABC: 774, Radio National, and News Radio; also Fairfax affiliates 3AW (talk) and Magic (easy listening). For sport fans and enthusiasts there is SEN 1116. Melbourne has many community run stations that serve alternative interests, such as 3CR and 3KND (Indigenous). Many suburbs have low powered community run stations serving local audiences.[200]

Governance

The governance of Melbourne is split between the government of Victoria and the 27 cities and four shires that make up the metropolitan area. There is no ceremonial or political head of Melbourne, but the Lord Mayor of the City of Melbourne often fulfils such a role as a first among equals.[201]

The local councils are responsible for providing the functions set out in the Local Government Act 1989[202] such as urban planning and waste management. Most other government services are provided or regulated by the Victorian state government, which governs from Parliament House in Spring Street. These include services associated with local government in other countries and include public transport, main roads, traffic control, policing, education above preschool level, health and planning of major infrastructure projects.

Infrastructure

In 2012, Mercer Consulting ranked Melbourne's infrastructure 34th in the world, behind Sydney (ranked 8th in the world), and Perth (ranked 25th in the world) .[203]

Health

The Victorian Government's Department of Health oversees about 30 public hospitals in the Melbourne metropolitan region and 13 health services organisations.[204]

There are many major medical, neuroscience and biotechnology research institutions located in Melbourne: St. Vincent's Institute of Medical Research, Australian Stem Cell Centre, the Burnet Institute, Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute, Victorian Institute of Chemical Sciences, Brain Research Institute, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research, and the Melbourne Neuropsychiatry Centre.

Other institutions include the Howard Florey Institute, the Murdoch Childrens Research Institute, Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute and the Australian Synchrotron.[205] Many of these institutions are associated with and are located near universities. Melbourne also is the home of the Royal Children's Hospital and the Monash Children's Hospital.

Among Australian capital cities, Melbourne ties with Canberra in first place for the highest male life expectancy (80.0 years) and ranks second behind Perth in female life expectancy (84.1 years).[206]

Transport

Like many Australian cities, Melbourne has a high dependency on the automobile for transport,[207] particularly in the outer suburban areas where the largest number of cars are bought,[208] with a total of 3.6 million private vehicles using 22,320 km (13,870 mi) of road, and one of the highest lengths of road per capita in the world.[207] The early 20th century saw an increase in popularity of automobiles, resulting in large-scale suburban expansion and a tendency towards the development of urban sprawl–like all Australian cities, inhabitants would live in the suburbs and commute to the city for work.[209] By the mid 1950s there was just under 200 passenger vehicles per 1000 people, and by 2013 there was 600 passenger vehicles per 1000 people.[210] Today it has an extensive network of freeways and arterial roadways used by private vehicles including freight as well as public transport systems including buses and taxis. Major highways feeding into the city include the Eastern Freeway, Monash Freeway and West Gate Freeway (which spans the large West Gate Bridge), whilst other freeways circumnavigate the city or lead to other major cities, including CityLink (which spans the large Bolte Bridge), Eastlink, the Western Ring Road, Calder Freeway, Tullamarine Freeway (main airport link) and the Hume Freeway which links Melbourne and Sydney.[211]

Melbourne has an integrated public transport system based around extensive train, tram, bus and taxi systems. Flinders Street station was the world's busiest passenger station in 1927 and Melbourne's tram network overtook Sydney's to become the world's largest in the 1940s. From the 1940s, public transport use in Melbourne declined due to a rapid expansion of the road and freeway network, with the largest declines in tram and bus usage.[212] This decline quickened in the early 1990s due to large public transport service cuts.[212] The operations of Melbourne's public transport system was privatised in 1999 through a franchising model, with operational responsibilities for the train, tram and bus networks licensed to private companies.[213] After 1996 there was a rapid increase in public transport patronage due to growth in employment in central Melbourne, with the mode share for commuters increasing to 14.8% and 8.4% of all trips.[214][212] A target of 20% public transport mode share for Melbourne by 2020 was set by the state government in 2006.[215] Since 2006 public transport patronage has grown by over 20%.[215]

La red ferroviaria de Melbourne se remonta a la época de la fiebre del oro de la década de 1850, y en la actualidad consta de 218 estaciones suburbanas en 16 líneas que parten de City Loop , un sistema de metro en su mayoría subterráneo alrededor del CBD. La estación de Flinders Street , el centro ferroviario más concurrido de Australia , sirve a toda la red y sigue siendo un importante lugar de reunión e hito de Melbourne. [216] La ciudad tiene conexiones ferroviarias con ciudades victorianas regionales, así como servicios ferroviarios interestatales directos que parten de la otra terminal ferroviaria importante de Melbourne, la estación Southern Cross , en Docklands. El Overland a Adelaide sale dos veces por semana, mientras que elXPT a Sydney sale dos veces al día. En el año fiscal 2017-2018, la red ferroviaria de Melbourne registró 240,9 millones de viajes de pasajeros, el mayor número de pasajeros de su historia. [217] Muchas líneas ferroviarias, junto con líneas especiales y patios ferroviarios , también se utilizan para el transporte de mercancías. [ cita requerida ]

La red de tranvías de Melbourne data del boom terrestre de la década de 1880 y, a partir de 2021, consta de 250 km (155,3 millas) de doble vía, 475 tranvías, 25 rutas y 1.763 paradas de tranvía , [218] lo que la convierte en la más grande del mundo. [22] [219] En 2017-2018, 206,3 millones de viajes de pasajeros se realizaron en tranvía. [217] Alrededor del 75 por ciento de la red de tranvías de Melbourne comparte espacio vial con otros vehículos, mientras que el resto de la red está separada o son rutas de tren ligero . [218] Los tranvías de Melbourne son reconocidos como activos culturales icónicos y una atracción turística. Los tranvías Heritage operan en la ruta gratuita City Circle, intended for visitors to Melbourne, and heritage restaurant trams travel through the city and surrounding areas during the evening.[220] Melbourne's bus network consists of almost 300 routes which mainly service the outer suburbs and fill the gaps in the network between rail and tram services.[220][221] 127.6 million passenger trips were recorded on Melbourne's buses in 2013–2014, an increase of 10.2 percent on the previous year.[222]

Ship transport is an important component of Melbourne's transport system. The Port of Melbourne is Australia's largest container and general cargo port and also its busiest. The port handled two million shipping containers in a 12-month period during 2007, making it one of the top five ports in the Southern Hemisphere.[223] Station Pier on Port Phillip Bay is the main passenger ship terminal with cruise ships and the Spirit of Tasmania ferries which cross Bass Strait to Tasmania docking there.[224] Ferries and water taxis run from berths along the Yarra River as far upstream as South Yarra and across Port Phillip Bay.

Melbourne tiene cuatro aeropuertos . El aeropuerto de Melbourne , en Tullamarine , es la principal puerta de entrada nacional e internacional de la ciudad y la segunda más transitada de Australia. El aeropuerto es la base de operaciones de la aerolínea de pasajeros Jetstar y de las aerolíneas de carga Australian airExpress y Toll Priority , y es un centro importante para Qantas y Virgin Australia . Aeropuerto de Avalon , ubicado entre Melbourne y Geelong, es un centro secundario de Jetstar. También se utiliza como instalación de transporte y mantenimiento. Los autobuses y los taxis son las únicas formas de transporte público desde y hacia los principales aeropuertos de la ciudad. Las instalaciones de ambulancia aérea están disponibles para el transporte nacional e internacional de pacientes. [225] Melbourne también tiene un importante aeropuerto de aviación general, el aeropuerto Moorabbin en el sureste de la ciudad, que también maneja una pequeña cantidad de vuelos de pasajeros. El aeropuerto de Essendon , que alguna vez fue el principal aeropuerto de la ciudad, también maneja vuelos de pasajeros, aviación general y algunos vuelos de carga. [226]

The city also has a bicycle sharing system that was established in 2010[227] and uses a network of marked road lanes and segregated cycle facilities.

Utilities

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

El almacenamiento y suministro de agua para Melbourne está gestionado por Melbourne Water , que es propiedad del gobierno de Victoria. La organización también es responsable de la gestión del alcantarillado y de las principales captaciones de agua de la región, así como de la planta desalinizadora de Wonthaggi y el Oleoducto Norte-Sur . El agua se almacena en una serie de depósitos ubicados dentro y fuera del área metropolitana de Melbourne. La presa más grande, la presa del río Thomson , ubicada en los Alpes victorianos, es capaz de contener alrededor del 60% de la capacidad de agua de Melbourne, [228] mientras que presas más pequeñas como la presa Upper Yarra , el embalse Yan Yean y el embalse Cardinia llevar suministros secundarios.

El gas es suministrado por tres empresas distribuidoras:

- AusNet Services , que suministra gas desde los suburbios del interior del oeste de Melbourne hasta el suroeste de Victoria.

- Multinet Gas , que suministra gas desde los suburbios del interior del este de Melbourne hasta el este de Victoria. (propiedad de SP AusNet después de la adquisición, pero continúa comercializándose con la marca Multinet Gas)

- Australian Gas Networks , que suministra gas desde los suburbios del norte del interior de Melbourne hasta el norte de Victoria, así como la mayor parte del sureste de Victoria.

La electricidad es proporcionada por cinco empresas distribuidoras:

- Citipower , que proporciona energía al CBD de Melbourne y a algunos suburbios del interior

- Powercor, which provides power to the outer western suburbs, as well as all of western Victoria (Citipower and Powercor are owned by the same entity)

- Jemena, which provides power to the northern and inner western suburbs

- United Energy, which provides power to the inner eastern and southeastern suburbs, and the Mornington Peninsula

- AusNet Services, which provides power to the outer eastern suburbs and all of the north and east of Victoria.

Numerous telecommunications companies provide Melbourne with terrestrial and mobile telecommunications services and wireless internet services and at least since 2016 Melbourne offers a free public WiFi which allows for up to 250 MB per device in some areas of the city.

Crime

Melbourne tiene una tasa de criminalidad moderadamente baja, ocupando el décimo octavo para la Seguridad Personal en The Economist ' 2021 Segura Índice de Ciudades s, poniéndolo en el segundo mejor categoría de nivel 'alto de seguridad'. [229] Los informes sobre delitos en Victoria cayeron un 7,8 por ciento en 2018 a su nivel más bajo en tres años, con 5.922 casos por cada 100.000 personas. [230] El centro de la ciudad de Melbourne (CBD) registró la tasa de incidentes más alta de las áreas del gobierno local en Victoria. [230]

Ver también

- Melway (el directorio de calles nativo y la fuente de información general en Melbourne)

- Melbourne , el artículo de viaje del proyecto hermano Wikivoyage

Liza

- Lista de suburbios de Melbourne

- Lista de museos en Melbourne

- Lista de personas de Melbourne

- List of songs about Melbourne

- Local government in Victoria

Notes

- ^ In British received pronunciation and General American English the variant /ˈmɛlbɔːrn/ MEL-born is also accepted.[8]

- ↑ El uso del término Melburnian se remonta a 1876, donde el caso de Melburnian sobre Melbournian se hizo en lapublicación de Melbourne Grammar School , The Melburnian . "El diptongo, ' ou ' no es un diptongo latino: por lo tanto, argumentamos de esta manera, Melburnia sería [la] forma latina del nombre, y de ahí proviene Melburnian ". [11] [12]

- ^ De acuerdo con la fuente de la Oficina de Estadísticas de Australia, Inglaterra , Escocia , China continental y las Regiones Administrativas Especiales de Hong Kong y Macao se enumeran por separado

- ^ As a percentage of 4,207,291 persons who nominated their ancestry at the 2016 census.

- ^ The Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who nominate "Australian" as their ancestry are part of the Anglo-Celtic group.[179]

- ^ Of any ancestry. Includes those identifying as Aboriginal Australians or Torres Strait Islanders. Indigenous identification is separate to the ancestry question on the Australian Census and persons identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander may identify any ancestry.

References

- ^ a b "3218.0 - crecimiento de la población regional, Australia, 2018-19, POBLACIÓN RESIDENTE ESTIMADA - Estados y territorios - áreas estadísticas de la mayor ciudad capital, 30 de junio de 2019" . Oficina de Estadísticas de Australia . 25 de marzo de 2020 . Consultado el 25 de marzo de 2020 .

- ^ "Censo de población y vivienda de 2016: perfil general de la comunidad" . Oficina de Estadísticas de Australia. 2017 . Consultado el 28 de septiembre de 2021 .

- ^ "Gran distancia del círculo entre MELBOURNE y CANBERRA" . Geociencia Australia. Marzo de 2004.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and ADELAIDE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and SYDNEY". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and BRISBANE". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ "Great Circle Distance between MELBOURNE and PERTH". Geoscience Australia. March 2004.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180; Butler, S., ed. (2013). "Melbourne" . Diccionario Macquarie (6ª ed.). Sídney: Macmillan Publishers Group Australia 2015. ISBN 978-18-7642-966-9.

- ^ "Censo de población y vivienda de 2016" .

- ^ "Directorio de gobierno local victoriano" (PDF) . Departamento de Planificación y Desarrollo Comunitario, Gobierno de Victoria . pag. 11. Archivado desde el original (PDF) el 15 de septiembre de 2009 . Consultado el 11 de septiembre de 2009 .

- ^ Serie de adiciones del diccionario inglés de Oxford , iii, sv " Melburnian ".

- ^ Macquarie Dictionary, Fourth Edition (2005). Or less commonly Melbournites. Melbourne, The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd. ISBN 1-876429-14-3.

- ^ a b c "History of the City of Melbourne" (PDF). City of Melbourne. November 1997. pp. 8–10. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ Latimore, Jack (18 May 2018). "We must return all our landmarks to their Indigenous names". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ↑ a b Lewis, Miles (1995). Melbourne: la historia y el desarrollo de la ciudad (2ª ed.). Melbourne: Ciudad de Melbourne. pag. 25. ISBN 0-949624-71-3.

- ↑ a b Cervero, Robert B. (1998). La metrópolis del tránsito: una investigación global . Chicago: Island Press. pag. 320. ISBN 1-55963-591-6.

- ^ Davidson, Jim (2 de agosto de 2014). "Ascenso y caída del imperio británico visto a través de sus ciudades" . El australiano . Australia. Consultado el 7 de septiembre de 2018.

- ^ "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act" (PDF). Department of the Attorney-General, Government of Australia. p. 45 (Section 125). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ^ "The Global Financial Centres Index 28" (PDF). Long Finance. September 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ↑ a b Stephanie Chalkley-Rhoden (16 de agosto de 2017). "La ciudad más habitable del mundo: Melbourne ocupa el primer lugar por séptimo año consecutivo" . Corporación Australiana de Radiodifusión . Consultado el 17 de agosto de 2017 .

- ^ "Gobierno describe la visión para el puerto de Melbourne Freight Hub" (Comunicado de prensa). 2006. Archivado desde el original el 8 de julio de 2012 . Consultado el 26 de julio de 2007 .

- ^ a b "Inversión en transporte Capítulo 3 - Este / Oeste, sección 3.1.2 - Red de tranvía" (PDF) . Departamento de Transporte, Gobierno de Victoria . Consultado el 21 de noviembre de 2009 .

- ^ Gary Presland, Los primeros residentes de la región occidental de Melbourne , (edición revisada), Harriland Press, 1997. ISBN 0-646-33150-7

- ^ a b "Conexiones indígenas al sitio" (PDF) . rbg.vic.gov.au . Archivado desde el original (PDF) el 8 de septiembre de 2008 . Consultado el 28 de abril de 2021 .

- ↑ Gary Presland, Aboriginal Melbourne: The Lost Land of the Kulin People , Harriland Press (1985), Segunda edición 1994, ISBN 0-9577004-2-3

- ^ a b c "Fundación del Acuerdo" . Historia de la ciudad de Melbourne . Ciudad de Melbourne. 1997. Archivado desde el original el 20 de febrero de 2011 . Consultado el 13 de julio de 2010 .

- ^ a b Isabel Ellender y Peter Christiansen, Gente de Merri Merri. The Wurundjeri in Colonial Days , Comité de Gestión de Merri Creek, 2001 ISBN 0-9577728-0-7

- ^ Dunstan, Joseph (26 June 2021). "Melbourne's birth destroyed Bunurong and Wurundjeri boundaries. 185 years on, they've been redrawn". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Button, James (4 October 2003). "Secrets of a forgotten settlement". The Age. Melbourne: Fairfax Media. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- ^ Annear, Robyn (2005). Bearbrass: Imagining Early Melbourne. Melbourne, Victoria: Black Inc. p. 6. ISBN 1863953973.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 91.

- ^ "Melbourne's Godfather". The West Australian. 50 (14, 996). Western Australia. 14 July 1934. p. 6. Retrieved 20 September 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Roads". City of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ "29 de enero de 1938 - LLAMARON MELBOURNE BAREBRASS - Trove" . Trove.nla.gov.au. 29 de enero de 1938 . Consultado el 16 de marzo de 2019 .

- ^ "Gaceta del gobierno de Nueva Gales del Sur (Sydney, NSW)" . Trove . Biblioteca Nacional de Australia . Consultado el 1 de octubre de 2020 .

- ^ Historia de las subastas de Phoenix. "Lista de oficinas de correos" . Consultado el 22 de enero de 2021 .

- ^ James Boyce, 1835: La fundación de Melbourne y la conquista de Australia, Black Inc, 2011, página 151 citando a Richard Broome, "Victoria" en McGrath (ed.), Terreno impugnado: 129