Brachiopod

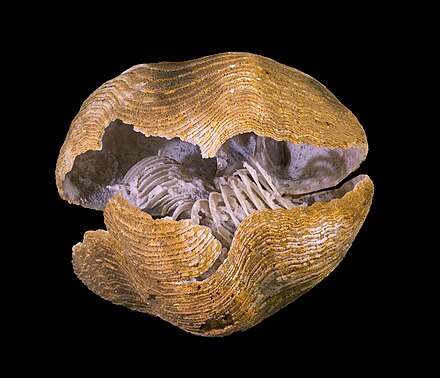

Brachiopods (/ˈbrækioʊˌpɒd/), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, while the front can be opened for feeding or closed for protection. Two major categories are traditionally recognized, articulate and inarticulate brachiopods. The word "articulate" is used to describe the tooth-and-groove structures of the valve-hinge which is present in the articulate group, and absent from the inarticulate group. This is the leading diagnostic skeletal feature, by which the two main groups can be readily distinguished as fossils. Articulate brachiopods have toothed hinges and simple, vertically-oriented opening and closing muscles. Conversely, inarticulate brachiopods have weak, untoothed hinges and a more complex system of vertical and oblique (diagonal) muscles used to keep the two valves aligned. In many brachiopods, a stalk-like pedicleprojects from an opening near the hinge of one of the valves, known as the pedicle or ventral valve. The pedicle, when present, keeps the animal anchored to the seabed but clear of sediment which would obstruct the opening.

Brachiopod lifespans range from three to over thirty years. Ripe gametes (ova or sperm) float from the gonads into the main coelom and then exit into the mantle cavity. The larvae of inarticulate brachiopods are miniature adults, with lophophores that enable the larvae to feed and swim for months until the animals become heavy enough to settle to the seabed. The planktonic larvae of articulate species do not resemble the adults, but rather look like blobs with yolk sacs, and remain among the plankton for only a few days before leaving the water column upon metamorphosing.

While traditional classification of brachiopods separate them into distinct inarticulate and articulate groups, two approaches appeared in the 1990s. One approach groups the inarticulate Craniida with articulate brachiopods, since both use layers of calcareous minerals their shell; the other approach considers the Craniida to be a separate third group, as their outer organic layer is distinct from that of both the linguliforms ("typical" inarticulates) and rhynchonelliforms (articulates). However, some taxonomists believe it is premature to suggest higher levels of classification such as order and recommend a bottom-up approach that identifies genera and then groups these into intermediate groups. Traditionally, brachiopods have been regarded as members of, or as a sister group to, the deuterostomes, a superphylum that includes chordates and echinoderms. One type of analysis of the evolutionary relationships of brachiopods has always placed brachiopods as protostomes while another type has split between placing brachiopods among the protostomes or the deuterostomes.

.jpg/440px-Pygites_diphyoides_(d'Orbigny).jpg)