Crinoid

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea, one of the classes of the phylum Echinodermata, which also includes the starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins and sea cucumbers.[3] Those crinoids which, in their adult form, are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, being members of the largest crinoid order, Comatulida.

Adult crinoids are characterised by having the mouth located on the upper surface. This is surrounded by feeding arms, and is linked to a U-shaped gut, with the anus being located on the oral disc near the mouth. Although the basic echinoderm pattern of fivefold symmetry can be recognised, in most crinoids the five arms are subdivided into ten or more. These have feathery pinnules and are spread wide to gather planktonic particles from the water. At some stage in their lives, most crinoids have a stem used to attach themselves to the substrate, but many live attached only as juveniles and become free-swimming as adults.

There are only about 600 living species of crinoid,[4] but the class was much more abundant and diverse in the past. Some thick limestone beds dating to the mid-Paleozoic to Jurassic eras are almost entirely made up of disarticulated crinoid fragments.[5][6][7]

The name "Crinoidea" comes from the Ancient Greek word κρίνον (krínon), "a lily", with the suffix –oid meaning "like".[8][9] They live in both shallow water[10] and in depths as great as 9,000 meters (30,000 ft).[11] Those crinoids which in their adult form are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk are commonly called sea lilies,[12] while the unstalked forms are called feather stars[13] or comatulids, being members of the largest crinoid order, Comatulida.[14]

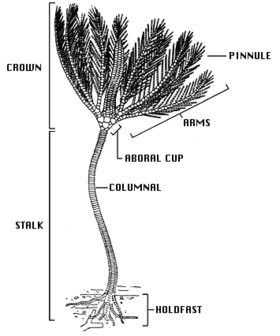

The basic body form of a crinoid is a stem (not present in adult feather stars) and a crown consisting of a cup-like central body known as the theca, and a set of five rays or arms, usually branched and feathery. The mouth and anus are both located on the upper side of the theca, making the dorsal (upper) surface the oral surface, unlike in the other echinoderm groups such as the sea urchins, starfish and brittle stars where the mouth is on the underside.[15] The numerous calcareous plates make up the bulk of the crinoid, with only a small percentage of soft tissue. These ossicles fossilise well and there are beds of limestone dating from the Lower Carboniferous around Clitheroe, England, formed almost exclusively from a diverse fauna of crinoid fossils.[16]

The stem of sea lilies is composed of a column of highly porous ossicles which are connected by ligamentary tissue. It attaches to the substrate with a flattened holdfast or with whorls of jointed, root-like structures known as cirri. Further cirri may occur higher up the stem. In crinoids that attach to hard surfaces, the cirri may be robust and curved, resembling birds' feet, but when crinoids live on soft sediment, the cirri may be slender and rod-like. Juvenile feather stars have a stem, but this is later lost, with many species retaining a few cirri at the base of the crown. The majority of living crinoids are free-swimming and have only a vestigial stalk. In those deep-sea species that still retain a stalk, it may reach up to 1 m (3 ft) in length (although usually much smaller), and fossil species are known with 20 m (66 ft) stems,[17] the largest recorded crinoid having a stem 40 m (130 ft) in length.[18]