Este artículo necesita citas adicionales para su verificación . ( junio de 2013 ) ( Aprenda cómo y cuándo eliminar este mensaje de plantilla ) |

Techar con paja es el oficio de construir un techo con vegetación seca como paja , caña de agua , juncia ( Cladium mariscus ), juncos , brezos o ramas de palmera , colocando capas de vegetación para eliminar el agua del techo interior. Dado que la mayor parte de la vegetación permanece seca y densamente compacta, atrapando el aire, el techado de paja también funciona como aislante. Es un método de techado muy antiguo y se ha utilizado tanto en climas tropicales como templados.. Los constructores de países en desarrollo todavía emplean paja, generalmente con vegetación local de bajo costo. Por el contrario, en algunos países desarrollados es la elección de algunas personas adineradas que desean una apariencia rústica para su hogar, desean un techo más ecológico o que han comprado una morada originalmente con techo de paja.

Historia [ editar ]

Los métodos de techado de paja se han transmitido tradicionalmente de generación en generación, y numerosas descripciones de los materiales y métodos utilizados en Europa durante los últimos tres siglos sobreviven en archivos y publicaciones antiguas.

En algunos países ecuatoriales, la paja es el material local predominante para los techos y, a menudo, las paredes . Existen diversas técnicas de construcción del antiguo refugio haleiano hawaiano elaborado con hojas de ti locales ( Cordyline fruticosa ), lauhala ( Pandanus tectorius ) [1] o pasto pili ( Heteropogon contortus ).

Las hojas de palma también se utilizan a menudo. Por ejemplo, en Na Bure, Fiji , los thatchers combinan techos de hojas de palma abanico con paredes de caña en capas. En Dominica se utilizan techos de hojas de palma emplumadas. [2] Los techos de paja de Alang-alang ( Imperata cylindrica ) se utilizan en Hawai y Bali . En el sudeste asiático, las hojas de palma de manglar nipa se utilizan como material de techo de paja conocido como vivienda attap . En Bali, Indonesia , las fibras negras de Arenga pinnata llamadas ijuk también se utilizan como materiales para techos de paja, generalmente utilizados en el techo de los templos balineses y las torres de meru. [3] Caña de azúcarLos techos de hojas se utilizan en las casas tribales Kikuyu en Kenia . [4] [5]

La vegetación silvestre como el junco de agua ( Phragmites australis ), la espadaña / cola de gato ( Typha spp.), La retama ( Cytisus scoparius ), el brezo ( Calluna vulgaris ) y los juncos ( Juncus spp. Y Schoenoplectus lacustris ) probablemente se utilizó para cubrir refugios viviendas primitivas en Europa en el Paleolítico tardío, pero hasta ahora no se ha recuperado ninguna evidencia arqueológica directa de esto. La gente probablemente comenzó a usar paja en el período Neolítico cuando cultivaron cereales por primera vez, pero una vez más, no sobrevive ninguna evidencia arqueológica directa de paja para techar con paja en Europa antes del período medieval temprano. [6] [ página necesaria ]

Muchos pueblos indígenas de las Américas, como la antigua civilización maya, Mesoamérica, el imperio Inca y la Triple Alianza (azteca), vivían en edificios con techo de paja. Es común ver edificios con techo de paja en áreas rurales de la península de Yucatán, así como muchos asentamientos en otras partes de América Latina, que se asemejan mucho al método de construcción de ancestros lejanos. Los primeros estadounidenses que encontraron los europeos vivían en estructuras techadas con corteza o piel colocada en paneles que se podían agregar o quitar para ventilación, calefacción y enfriamiento. La evidencia de los muchos edificios complejos con material para techos a base de fibra no se redescubrió hasta principios de la década de 2000. Los colonos franceses y británicos construyeron viviendas temporales con techo de paja con vegetación local tan pronto como llegaron a Nueva Francia y Nueva Inglaterra, pero cubrieron casas más permanentes con tejas de madera.

En la mayor parte de Inglaterra, la paja siguió siendo el único material para techos disponible para la mayor parte de la población en el campo, en muchas ciudades y pueblos, hasta finales del siglo XIX. [7] La distribución comercial de pizarra galesa comenzó en 1820, y la movilidad proporcionada por los canales y luego los ferrocarriles hizo que otros materiales estuvieran fácilmente disponibles. Aún así, el número de propiedades con techo de paja en realidad aumentó en el Reino Unido a mediados del siglo XIX a medida que la agricultura se expandió, pero luego volvió a disminuir a fines del siglo XIX debido a la recesión agrícola y la despoblación rural. Un informe de 2013 estimó que había 60.000 propiedades en el Reino Unido con techo de paja; suelen estar hechos de paja larga, caña de trigo peinada o caña de agua. [8]

Gradualmente, el techo de paja se convirtió en una marca de pobreza y el número de propiedades con techo de paja disminuyó gradualmente, al igual que el número de trabajadores profesionales. La paja se ha vuelto mucho más popular en el Reino Unido durante los últimos 30 años y ahora es un símbolo de riqueza en lugar de pobreza. En el Reino Unido hay aproximadamente 1.000 thatchers a tiempo completo, [9] y el techado de paja se está volviendo popular nuevamente debido al renovado interés en preservar edificios históricos y utilizar materiales de construcción más sostenibles. [10]

Trabajos de paja en una casa en Mecklenburg, Alemania

Iglesia de los pescadores Born auf dem Darß

Cabañas con techo de paja en las dunas de arena , Dinamarca

Casa con techo de paja en Kilmore Quay , Irlanda

Cahire Breton cottages at Plougoumelen, Brittany, France

Thatched roofs in Kerene (Ethiopia

Material[edit]

Thatch is popular in the United Kingdom, Germany, The Netherlands, Denmark, parts of France, Sicily, Belgium and Ireland. There are more than 60,000 thatched roofs in the United Kingdom and over 150,000 in the Netherlands.[11][citation needed] Good quality straw thatch can last for more than 50 years when applied by a skilled thatcher. Traditionally, a new layer of straw was simply applied over the weathered surface, and this "spar coating" tradition has created accumulations of thatch over 7’ (2.1 m) thick on very old buildings. The straw is bundled into "yelms" before it is taken up to the roof and then is attached using staples, known as "spars", made from twisted hazel sticks. Over 250 roofs in Southern England have base coats of thatch that were applied over 500 years ago, providing direct evidence of the types of materials that were used for thatching in the medieval period.[6][page needed] Almost all of these roofs are thatched with wheat, rye, or a "maslin" mixture of both. Medieval wheat grew to almost 6 feet (1.8 m) tall in very poor soils and produced durable straw for the roof and grain for baking bread.[citation needed]

Technological change in the farming industry significantly affected the popularity of thatching. The availability of good quality thatching straw declined in England after the introduction of the combine harvester in the late 1930s and 1940s, and the release of short-stemmed wheat varieties. Increasing use of nitrogen fertiliser in the 1960s–70s also weakened straw and reduced its longevity. Since the 1980s, however, there has been a big increase in straw quality as specialist growers have returned to growing older, tall-stemmed, "heritage" varieties of wheat such as Squareheads Master (1880), N59 (1959), Rampton Rivet (1937), Victor (1910) and April Bearded (early 1800s)] in low input/organic conditions.[12]

In the UK it is illegal under the Plant Variety and Seeds Act 1964 (with many amendments) for an individual or organisation to give, trade or sell seed of an older variety of wheat (or any other agricultural crop) to a third party for growing purposes, subject to a significant fine.[13] Because of this legislation, thatchers in the UK can no longer obtain top quality thatching straw grown from traditional, tall-stemmed varieties of wheat.

All evidence indicates that water reed was rarely used for thatching outside of East Anglia.[7] It has traditionally been a "one coat" material applied in a similar way to how it is used in continental Europe. Weathered reed is usually stripped and replaced by a new layer. It takes 4–5 acres of well-managed reed bed to produce enough reed to thatch an average house, and large reed beds have been uncommon in most of England since the Anglo-Saxon period. Over 80% of the water reed used in the UK is now imported from Turkey, Eastern Europe, China and South Africa. Though water reed might last for 50 years or more on a steep roof in a dry climate, modern imported water reed on an average roof in England does not last any longer than good quality wheat straw. The lifespan of a thatched roof also depends on the skill of the thatcher, but other factors must be considered—such as climate, quality of materials, and the roof pitch.

In areas where palms are abundant, palm leaves are used to thatch walls and roofs. Many species of palm trees are called "thatch palm", or have "thatch" as part of their common names. In the southeastern United States, Native and pioneer houses were often constructed of palmetto-leaf thatch.[14][15][16] The chickees of the Seminole and Miccosukee are still thatched with palmetto leaves.

Thatching miscanthus field in Sandager, Denmark

Grassland with thatching grass on Imba Abba Salama Mt. in Haddinnet, Ethiopia

A closeup of the thatching.

Bundling technique used in straw thatching.

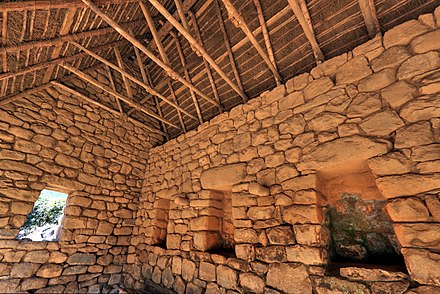

Inside view of a straw-thatched house.

Thatched roof with snow, Japan

Outside layer of moss and lichen growing on thatch.

Thatching by hay for making Pandals at Kolkata.

Thatched roof made of ijuk black arenga pinnata fibres, Besakih, Bali.

Heather thatching, Culloden, Scotland.

Maintenance in temperate climates[edit]

Good thatch does not require frequent maintenance. In England a ridge normally lasts 8–14 years, and re-ridging is required several times during the lifespan of a thatch. Experts no longer recommend covering thatch with wire netting, as this slows evaporation and reduces longevity. Moss can be a problem if very thick, but is not usually detrimental, and many species of moss are actually protective. The Thatcher's Craft, 1960, remains the most widely used reference book on the techniques used for thatching.[17] The thickness of a layer of thatch decreases over time as the surface gradually turns to compost and is blown off the roof by wind and rain. Thatched roofs generally need replacement when the horizontal wooden 'sways' and hair-pin 'spars', also known as 'gads' (twisted hazel staples) that fix each course become visible near the surface. It is not total depth of the thatch within a new layer applied to a new roof that determines its longevity, but rather how much weathering thatch covers the fixings of each overlapping course. “A roof is as good as the amount of correctly laid thatch covering the fixings.”[18]

Flammability[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (May 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Thatch is not as flammable as many people believe. It burns slowly, "like a closed book," thatchers say. The vast majority of fires are linked to the use of wood burners and faulty chimneys with degraded or poorly installed or maintained flues. Sparks from paper or burned rubbish can ignite dry thatch on the surface around a chimney. Fires can also begin when sparks or flames work their way through a degraded chimney and ignite the surrounding semi-charred thatch. This can be avoided by ensuring that the chimney is in good condition, which may involve stripping thatch immediately surrounding the chimney to the full depth of the stack. This can easily be done without stripping thatch over the entire roof. Insurance premiums on thatched houses are higher than average in part because of the perception that thatched roofs are a fire hazard, but also because a thatch fire can cause extensive smoke damage and a thatched roof is more expensive to replace than a standard tiled or slate roof. Workmen should never use open flame near thatch, and nothing should be burnt that could fly up the chimney and ignite the surface of the thatch. Spark arrestors usually cause more harm than good, as they are easily blocked and reduce air flow. All thatched roofs should have smoke detectors in the roof space. Spray-on fire retardant or pressure impregnated fire retardants can reduce the spread of flame and radiated heat output.

On new buildings, a solid fire retardant barrier over the rafters can make the thatch sacrificial in case of fire. If fireboards are used, they require a ventilation gap between boarding and thatch so that the roof can breathe, as condensation can be a significant problem in thin, single layer thatch. Condensation is much less of a problem on thick straw roofs, which also provide much better insulation since they do not need to be ventilated.

Performance[edit]

The performance of thatch depends on roof shape and design, pitch of roof, position—its geography and topography—the quality of material and the expertise of the thatcher.

Thatch has some natural properties that are advantageous to its performance. It is naturally weather-resistant, and when properly maintained does not absorb a lot of water. There should not be a significant increase to roof weight due to water retention. A roof pitch of at least 50 degrees allows precipitation to travel quickly down slope so that it runs off the roof before it can penetrate the structure.

Thatch is also a natural insulator, and air pockets within straw thatch insulate a building in both warm and cold weather. A thatched roof ensures that a building is cool in summer and warm in winter.

Thatch also has very good resistance to wind damage when applied correctly.

Advantages[edit]

Thatching materials range from plains grasses to waterproof leaves found in equatorial regions. It is the most common roofing material in the world, because the materials are readily available.[citation needed]

Because thatch is lighter, less timber is required in the roof that supports it.

Thatch is a versatile material when it comes to covering irregular roof structures. This fact lends itself to the use of second-hand, recycled and natural materials that are not only more sustainable, but need not fit exact standard dimensions to perform well.

Disadvantages[edit]

Thatched houses are harder to insure because of the perceived fire risk, and because thatching is labor-intensive, it is much more expensive to thatch a roof than to cover it with slate or tiles. Birds can damage a roof while they are foraging for grubs, and rodents are attracted by residual grain in straw.

Thatch has fallen out of favor in much of the industrialized world not because of fire, but because thatching has become very expensive and alternative 'hard' materials are cheaper—but this situation is slowly changing. There are about 60,000 thatched roofs in the UK, of which 50–80 suffer a serious fire each year, most of these being completely destroyed. The cost to the Fire Brigade is £1.3m per annum.[19] Many more thatched roofs are being built every year.[citation needed]

New thatched roofs were forbidden in London in 1212 following a major fire,[20] and existing roofs had to have their surfaces plastered to reduce the risk of fire. The modern Globe Theatre is one of the few thatched buildings in London (others can be found in the suburb of Kingsbury), but the Globe's modern, water reed thatch is purely for decorative purpose and actually lies over a fully waterproofed roof built with modern materials. The Globe Theatre, opened in 1997, was modelled on the Rose, which was destroyed by a fire on a dry June night in 1613 when a burning wad of cloth ejected from a special effects cannon during a performance set light to the surface of the thatch. The original Rose Theatre was actually thatched with cereal straw, a sample of which was recovered by Museum of London archaeologists during the excavation of the site in the 1980s.[21]

Some claim thatch cannot cope with regular snowfall but, as with all roofing materials, this depends on the strength of the underlying roof structure and the pitch of the surface. A law passed in 1640 in Massachusetts outlawed the use of thatched roofs in the colony for this reason. Thatch is lighter than most other roofing materials, typically around 34 kg/m2 (7 lb/sq ft), so the roof supporting it does not need to be so heavily constructed, but if snow accumulates on a lightly constructed thatched roof, it could collapse. A thatched roof is usually pitched between 45–55 degrees and under normal circumstances this is sufficient to shed snow and water. In areas of extreme snowfall, such as parts of Japan, the pitch is increased further.[22]

Archaeology[edit]

Some thatched roofs in the UK are extremely old and preserve evidence of traditional materials and methods that had long been lost. In northern Britain this evidence is often preserved beneath corrugated sheet materials and frequently comes to light during the development of smaller rural properties. Historic Scotland have funded several research projects into thatching techniques and these have revealed a wide range of materials including broom, heather, rushes, cereals, bracken, turf and clay and highlighted significant regional variation[23][24][25]

More recent examples include the Moirlanich Longhouse, Killin owned by the National Trust for Scotland (rye, bracken & turf)[26] and Sunnybrae Cottage, Pitlochry owned by Historic Scotland (rye, broom & turf)[27]

Examples[edit]

- Attap dwelling, Southeast Asia

- Blackhouse, Scotland, Ireland

- Chickee, Seminole

- Palapa, Mexico

- Roundhouse (dwelling), Iron Age European

- Teitos e pallozas, Asturias and Galicia, Spain

- Historic Villages of Shirakawa-gō and Gokayama

- Shinmei-zukuri

- Normandy, Brittany, France

See also[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thatching. |

- Dethatcher, for lawns

- Houses at Auvers, depiction in art

- Swiss cottage, Cahir Thatched cottage orné in Cahir, Ireland.

- Vernacular architecture

- Woodway House A thatched cob cottage orné in Devon, England.

- Withy A thatching material from willows

References[edit]

- ^ Thomson, Lex AJ; Englberger, Lois; Guarino, Luigi; Thaman, RR; Elevitch, Craig R (2006). "Pandanus tectorius (Pandanus)". In Elevitch, Craig R (ed.). Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry (PDF) (1.1 ed.). Hōlualoa, HI: Permanent Agriculture Resources (PAR). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-21.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-02-01.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Peter J. M. Nas (2003). The Indonesian Town Revisited, Volume 1 of Southeast Asian dynamics. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 215. ISBN 9783825860387. Archived from the original on 2017-03-13.

- ^ "Houses", Fiji, Polynesia, archived from the original on 2009-07-26.

- ^ Sedemsky, Matt (Nov 30, 2003), "Low-Tech Building Craze Hits Hawaii; Indigenous Thatched-Roof Hale Once Out of Favor, Now Seen as Status Symbol on the Islands", The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Letts 2000.

- ^ a b Moir, J; Letts, John (1999), "Thatch: Thatching in England 1790–1940", Research Transactions, English Heritage, 5.

- ^ "Cotswold Thatched Roofs". Cotswold Life. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

they are set to increase and some house builders are meeting the demand for new homes with thatched roofs.

- ^ Letts, John (2008), Survey (unpublished ed.).

- ^ "Magical thatched homes that will enchant you". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ https://www.riet.com/media/vfr/leden/downloads/rapporten/De%20Nederlandse%20rietdekmarkt%2020-5-2010.pdf

- ^ Letts, John (2007), Growing Straw for Thatching: a guide, The COHT (Conservation of Historic Thatch Committee.

- ^ Legislation, 1964, archived from the original on 2012-01-11.

- ^ Andrews, Charles Mclean; Andrews, Evangeline Walker, eds. (1981) [1945], Jonathan Dickinson's Journal or, God's Protecting Providence. Being the Narrative of a Journey from Port Royal in Jamaica to Philadelphia between August 23, 1696 to April 1, 1697, Florida Classics Library (reprint ed.), New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 11.

- ^ Pierce, Charles W (1970), Pioneer Life in Southeast Florida, Miami: University of Miami Press, pp. 53–4, ISBN 0-87024-163-X

- ^ Thatching from the Bayleaf Palm of Belize, Palomar, archived from the original on June 8, 2007, retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ^ Thatch, UK: HCT, archived from the original on 2012-01-11.

- ^ The Thatch & Thatching, UK: The East Anglia Master Thatchers Association, archived from the original on 2011-08-31.

- ^ "Thatching Advisory Service". Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ "Florilegium urbanum - Physical fabric - Regulations for building construction and fire safety". users.trytel.com. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Letts, John, Unpublished photos and sample records.

- ^ "Winter Japan at its Best". Addicted to Travel. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Walker, B, McGregor, C.& Stark, G 1996 Thatches and Thatching Techniques: A guide to conserving Scottish Thatching Traditions. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland Technical Advice Note 4.

- ^ Holden, T G 2010 Thatch, in Jenkins, M ed. The Traditional Building Materials of Scotland Building Scotland: Celebrating Scotland’s Traditional Buildings Materials. Historic Scotland

- ^ Holden, T G 1998 The Archaeology of Scottish Thatch. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland Technical Advice Note 13

- ^ Holden, T G 2012 Moirlanich Longhouse, Killin: Changing techniques in thatching. Vernacular Building 35, 39-47.

- ^ Holden, T G and Walker, B 2013 Sunnybrae Cottage, Pitlochry. Edinburgh: Historic Scotland Research report.

Bibliography[edit]

- Letts, John (2000) [1999], Smoke Blackened Thatch: a unique source of late medieval plant remains from Southern England, Reading & London: University of Reading and English Heritage.

Further reading[edit]

- Cox, Jo and Thorp, John R. L. (2001). Devon Thatch: An Illustrated History of Thatching and Thatched Buildings in Devon. Tiverton: Devon Books. ISBN 9781855227972

- William, Eurwyn (2010). "Chapter 5: Roofs". The Welsh Cottage. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. pp. 145–203. ISBN 978-1-871184-426.

External links[edit]

- The Thatcher's Craft, UK: Battley Brothers Limited, archived from the original on 2015-05-01.

- "Thatching in West Europe, from Asturias to Iceland", Research Award, Europa nostra, 2011, archived from the original on 2011-08-15.

- Thatching with Green Broom in Spain, Thatch, archived from the original on 2011-09-28, retrieved 2011-09-23.

- Devon County Council (2003). Thatch in Devon Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine