Este artículo necesita citas adicionales para su verificación . ( enero de 2011 ) ( Aprenda cómo y cuándo eliminar este mensaje de plantilla ) |

Parte de una serie sobre el |

|---|

| Historia de Francia |

|

| Cronología |

| Portal de Francia |

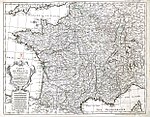

Galia ( latín : Gallia ) [1] fue una región de Europa occidental descrita por primera vez por los romanos. [2] Fue habitada por tribus celtas , que abarcan la actual Francia , Luxemburgo , Bélgica , la mayor parte de Suiza y partes del norte de Italia , los Países Bajos y Alemania , particularmente la orilla occidental del Rin . Cubrió un área de 494.000 km 2 (191.000 millas cuadradas). [3] Según Julio César, Galia se dividió en tres partes: Gallia Celtica , Belgica y Aquitania . Arqueológicamente, los galos fueron portadores de la cultura La Tène , que se extendió por toda la Galia, así como al este hasta Raetia , Noricum , Panonia y el suroeste de Germania durante los siglos V al I a.C. [4] Durante los siglos II y I a. C., la Galia cayó bajo el dominio romano: la Gallia Cisalpina fue conquistada en el 203 a. C. y la Gallia Narbonensis en el 123 a. C. Galia fue invadida después del 120 a. C. por los cimbrios y los teutones., quienes a su vez fueron derrotados por los romanos hacia el 103 a. C. Julio César finalmente sometió a las partes restantes de la Galia en sus campañas del 58 al 51 a. C.

El control romano de la Galia duró cinco siglos, hasta que el último estado romano , el Dominio de Soissons , cayó en manos de los francos en 486 d.C. Mientras que los galos celtas habían perdido sus identidades y lengua originales durante la Antigüedad tardía , se fusionaron en un galo- En la cultura romana , Gallia siguió siendo el nombre convencional del territorio a lo largo de la Alta Edad Media , hasta que adquirió una nueva identidad como el Reino Capeto de Francia en la alta época medieval. Gallia sigue siendo un nombre de Francia en griego moderno (Γαλλία) y latín moderno(además de las alternativas Francia y Francogallia ).

Nombre [ editar ]

Los nombres griegos y latinos Galatia (atestiguado por primera vez por Timeo de Tauromenium en el siglo IV a. C.) y Gallia se derivan en última instancia de un término étnico celta o clan Gal (a) -to- . [5] Se informó que los Galli de Gallia Celtica se referían a sí mismos como Celtae por César. La etimología popular helenística conectaba el nombre de los gálatas (Γαλάται, Galátai ) con la piel supuestamente "blanca como la leche" (γάλα, gála "leche") de los galos. [6] Los investigadores modernos dicen que está relacionado con gallu galés ,[7] Cornualles : galloes , [8] "capacidad, poder", [9] que significa "gente poderosa".

A pesar de la similitud superficial, el término inglés Galia no tiene relación con el latín Gallia . Se deriva de los franceses Gaule , sí se deriva del antiguo franco * Walholant (a través de una forma latinizada * Walula ), [10] , literalmente, la "Tierra de los extranjeros / romanos". * Walho- es un reflejo del proto-germánico * walhaz , "extranjero, persona romanizada", exónimo que los germánicos aplican a los celtas y a los latinos de forma indiscriminada. Es afín a los nombres de Gales , Cornualles., Valonia y Valaquia . [11] El germánico w- se traduce regularmente como gu- / g- en francés (cf. guerre "war", garder "ward", Guillaume "William"), y el histórico diptongo au es el resultado regular de al antes de un siguiente consonante (cf. cheval ~ chevaux ). Gaule francés o Gaulle no se pueden derivar del latín Gallia , ya que g se convertiría en j antes de un(cf. gamba > jambe ), y el diptongo au sería inexplicable; el resultado habitual del latín Gallia es Jaille en francés, que se encuentra en varios topónimos occidentales, como La Jaille-Yvon y Saint-Mars-la-Jaille . [12] [13] El walha protogermánico * se deriva en última instancia del nombre de los Volcae . [14]

Tampoco relacionado, a pesar de la similitud superficial, es el nombre Gael . [16] La palabra irlandesa gall significaba originalmente "un galo", es decir, un habitante de la Galia, pero su significado se amplió más tarde a "extranjero", para describir a los vikingos y, más tarde, a los normandos . [17] Las palabras dicotómicas gael y gall se usan a veces juntas para contrastar, por ejemplo, en el libro del siglo XII Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib .

Como adjetivos, el inglés tiene dos variantes: galo y galo . Los dos adjetivos se utilizan como sinónimos, como "pertenecientes a la Galia o los galos", aunque la lengua celta o las lenguas que se hablan en la Galia se conocen predominantemente como galo .

Historia [ editar ]

Galia prerromana [ editar ]

Hay poca información escrita sobre los pueblos que habitaban las regiones de la Galia, salvo la que se puede extraer de las monedas. Por lo tanto, la historia temprana de los galos es predominantemente un trabajo de arqueología, y las relaciones entre su cultura material , las relaciones genéticas (cuyo estudio ha sido ayudado, en los últimos años, a través del campo de la arqueogenética ) y las divisiones lingüísticas rara vez coinciden.

Antes de la rápida propagación de la cultura de La Tène en el quinto a cuarto siglos antes de Cristo, el territorio del este y sur de Francia ya participó a finales de la Edad del Bronce cultura de urnas (c. 12 al 8º siglos antes de Cristo) de los cuales el temprano el trabajo del hierro Se desarrollaría la cultura de Hallstatt (siglos VII al VI a. C.). Hacia el 500 a. C., existe una fuerte influencia de Hallstatt en la mayor parte de Francia (excepto en los Alpes y el extremo noroeste).

A partir de este trasfondo de Hallstatt, durante los siglos VII y VI a.C. presumiblemente representando una forma temprana de la cultura celta continental , surge la cultura de La Tène, presumiblemente bajo la influencia mediterránea de las civilizaciones griega , fenicia y etrusca , esparcidas en varias de las primeras centros a lo largo del Sena , el Rin Medio y el Alto Elba . A finales del siglo V a. C., la influencia de La Tène se extiende rápidamente por todo el territorio galo. La cultura de La Tène se desarrolló y floreció a finales de la Edad del Hierro (desde el 450 a. C. hasta la conquista romana en el siglo I a. C.) en Francia ,Suiza , Italia , Austria , suroeste de Alemania , Bohemia , Moravia , Eslovaquia y Hungría . Más al norte se extendió la cultura contemporánea prerromana de la Edad del Hierro del norte de Alemania y Escandinavia .

La principal fuente de materiales sobre los celtas de la Galia fue Poseidonios de Apamea , cuyos escritos fueron citados por Timagenes , Julio César , el griego siciliano Diodorus Siculus y el geógrafo griego Estrabón . [18]

En el siglo IV y principios del III a. C., las confederaciones de clanes galos se expandieron mucho más allá del territorio de lo que se convertiría en la Galia romana (que define el uso del término "Galia" hoy), en Panonia, Iliria, el norte de Italia, Transilvania e incluso Asia Menor . En el siglo II a. C., los romanos describieron a Gallia Transalpina como distinta de Gallia Cisalpina . En sus Guerras de las Galias , Julio César distingue entre tres grupos étnicos en la Galia: los belgas en el norte (aproximadamente entre el Rin y el Sena ), los celtas en el centro y en Armórica , y los aquitanos.en el suroeste, el sureste ya estaba colonizado por los romanos. Si bien algunos estudiosos creen que los belgas al sur del Somme eran una mezcla de elementos celtas y germánicos, sus afiliaciones étnicas no se han resuelto definitivamente. Una de las razones es la interferencia política sobre la interpretación histórica francesa durante el siglo XIX.

Además de los galos, había otros pueblos que vivían en la Galia, como los griegos y fenicios que habían establecido puestos de avanzada como Massilia (actual Marsella ) a lo largo de la costa mediterránea. [19] Además, a lo largo de la costa mediterránea del sudeste, los ligures se había fusionado con los celtas para formar un Celto- de Liguria cultura.

Contacto inicial con Roma [ editar ]

En el siglo II a. C. la Galia mediterránea tenía un extenso tejido urbano y era próspera. Los arqueólogos conocen ciudades del norte de la Galia, incluida la capital de Biturigia, Avaricum ( Bourges ), Cenabum ( Orleans ), Autricum ( Chartres ) y el yacimiento excavado de Bibracte cerca de Autun en Saona y Loira, junto con varios castros (o oppida ) utilizado en tiempos de guerra. La prosperidad de la Galia mediterránea animó a Roma a responder a las peticiones de ayuda de los habitantes de Massilia , que se vieron atacados por una coalición de ligures y galos. [20]Los romanos intervinieron en la Galia en el 154 a. C. y nuevamente en el 125 a. C. [20] Mientras que en la primera ocasión fueron y vinieron, en la segunda se quedaron. [21] En 122 a. C. Domicio Ahenobarbo logró derrotar a los alobroges (aliados de los Salluvii ), mientras que en el año siguiente Quinto Fabio Máximo "destruyó" un ejército de los arvernos dirigido por su rey Bituitus , que había acudido en ayuda de los Alobroges. [21] Roma permitió que Massilia se quedara con sus tierras, pero añadió a sus propios territorios las tierras de las tribus conquistadas. [21]Como resultado directo de estas conquistas, Roma ahora controlaba un área que se extendía desde los Pirineos hasta el río bajo del Ródano , y al este hasta el valle del Ródano hasta el lago de Ginebra . [22] Hacia el 121 a. C. los romanos habían conquistado la región mediterránea llamada Provincia (más tarde llamada Gallia Narbonensis ). Esta conquista trastornó el predominio de los pueblos arvernos galos .

Conquista de Roma [ editar ]

El procónsul romano y el general Julio César empujaron a su ejército a la Galia en el 58 a. C., aparentemente para ayudar a los aliados gaulianos de Roma contra los helvetios que emigraron. Con la ayuda de varios clanes galos (por ejemplo, los heduos) logró conquistar casi toda la Galia. Si bien su ejército era tan fuerte como el de los romanos, la división interna entre las tribus galas garantizó una fácil victoria para César, y el intento de Vercingetorix de unir a los galos contra la invasión romana llegó demasiado tarde. [23] [24]Julio César fue controlado por Vercingetorix en un sitio de Gergovia, una ciudad fortificada en el centro de la Galia. Las alianzas de César con muchos clanes galos se rompieron. Incluso los heduos, sus más fieles partidarios, se unieron a los arvernos, pero los siempre leales Remi (mejor conocido por su caballería) y los lingones enviaron tropas para apoyar a César. Los Germani de los Ubii también enviaron caballería, que César equipó con caballos Remi. César capturó a Vercingetorix en la batalla de Alesia , que acabó con la mayoría de la resistencia gala a Roma.

Hasta un millón de personas (probablemente 1 de cada 5 de los galos) murieron, otro millón fueron esclavizados , [25] 300 clanes fueron subyugados y 800 ciudades fueron destruidas durante las Guerras de las Galias . [26] Toda la población de la ciudad de Avaricum (Bourges) (40.000 en total) fue masacrada. [27] Antes de la campaña de Julio César contra los helvecios (actual Suiza ), los helvéticos eran 263.000, pero después sólo quedaron 100.000, la mayoría de los cuales César tomó como esclavos . [28]

Galia romana [ editar ]

Después de que Galia fue absorbida como Gallia , un conjunto de provincias romanas, sus habitantes adoptaron gradualmente aspectos de la cultura romana y se asimilaron, lo que resultó en la cultura galo-romana distinta . [29] La ciudadanía fue concedida a todos en 212 por la Constitutio Antoniniana . Desde el siglo III al V, la Galia estuvo expuesta a las incursiones de los francos . El Imperio Galo , formado por las provincias de Galia, Bretaña e Hispania , incluida la pacífica Bética en el sur, se separó de Roma de 260 a 273. Además del gran número de nativos, Galia también se convirtió en el hogar de algunosCiudadanos romanos de otros lugares y también tribus germánicas y escitas inmigrantes como los alanos . [30]

Las prácticas religiosas de los habitantes se convirtieron en una combinación de prácticas romanas y celtas, con deidades celtas como Cobannus y Epona sometidas a interpretatio romana . [31] [32] El culto imperial y las religiones de misterio orientales también ganaron seguidores. Eventualmente, después de que se convirtió en la religión oficial del Imperio y el paganismo fue suprimido, el cristianismo ganó en los días crepusculares del Imperio Romano Occidental (mientras que el Imperio Romano Oriental cristianizado duró otros mil años, hasta la invasión de Constantinopla por los otomanos en 1453). ); también se estableció una pequeña pero notable presencia judía .

Se cree que el idioma galo sobrevivió hasta el siglo VI en Francia, a pesar de la considerable romanización de la cultura material local. [33] El último registro de galo hablado que se consideró plausiblemente creíble [33] se refería a la destrucción por los cristianos de un santuario pagano en Auvernia "llamado Vasso Galatae en lengua gala". [34] Coexistiendo con el latín, el galo ayudó a dar forma a los dialectos del latín vulgar que se convirtieron en francés. [35] [36] [37] [38] [39]

El latín vulgar en la región de Gallia adquirió un carácter claramente local, algunos de los cuales están atestiguados en grafitis, [39] que evolucionaron hacia los dialectos galorromances que incluyen el francés y sus parientes más cercanos. La influencia de las lenguas de sustrato se puede ver en los grafitis que muestran cambios de sonido que coincidían con los cambios que habían ocurrido anteriormente en las lenguas indígenas, especialmente el galo. [39] El latín vulgar en el norte de la Galia se convirtió en langues d'oil y franco-provenzal , mientras que los dialectos en el sur evolucionaron hacia el occitano y catalán moderno. tongues. Other languages held to be "Gallo-Romance" include the Gallo-Italic languages and the Rhaeto-Romance languages.

Frankish Gaul[edit]

Following Frankish victories at Soissons (AD 486), Vouillé (AD 507) and Autun (AD 532), Gaul (except for Brittany and Septimania) came under the rule of the Merovingians, the first kings of France. Gallo-Roman culture, the Romanized culture of Gaul under the rule of the Roman Empire, persisted particularly in the areas of Gallia Narbonensis that developed into Occitania, Gallia Cisalpina and to a lesser degree, Aquitania. The formerly Romanized north of Gaul, once it had been occupied by the Franks, would develop into Merovingian culture instead. Roman life, centered on the public events and cultural responsibilities of urban life in the res publica and the sometimes luxurious life of the self-sufficient rural villa system, took longer to collapse in the Gallo-Roman regions, where the Visigoths largely inherited the status quo in the early 5th century. Gallo-Roman language persisted in the northeast into the Silva Carbonaria that formed an effective cultural barrier, with the Franks to the north and east, and in the northwest to the lower valley of the Loire, where Gallo-Roman culture interfaced with Frankish culture in a city like Tours and in the person of that Gallo-Roman bishop confronted with Merovingian royals, Gregory of Tours.

Massalia (modern Marseille) silver coin with Greek legend, 5th–1st century BC.

Gold coins of the Gaul Parisii, 1st century BC, (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris).

Roman silver Denarius with the head of captive Gaul 48 BC, following the campaigns of Julius Caesar.

Gauls[edit]

Social structure, indigenous nation and clans[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The Druids were not the only political force in Gaul, however, and the early political system was complex, if ultimately fatal to the society as a whole. The fundamental unit of Gallic politics was the clan, which itself consisted of one or more of what Caesar called pagi. Each clan had a council of elders, and initially a king. Later, the executive was an annually-elected magistrate. Among the Aedui, a clan of Gaul, the executive held the title of Vergobret, a position much like a king, but his powers were held in check by rules laid down by the council.

The regional ethnic groups, or pagi as the Romans called them (singular: pagus; the French word pays, "region" [a more accurate translation is 'country'], comes from this term), were organized into larger multi-clan groups, which the Romans called civitates. These administrative groupings would be taken over by the Romans in their system of local control, and these civitates would also be the basis of France's eventual division into ecclesiastical bishoprics and dioceses, which would remain in place—with slight changes—until the French Revolution.

Although the individual clans were moderately stable political entities, Gaul as a whole tended to be politically divided, there being virtually no unity among the various clans. Only during particularly trying times, such as the invasion of Caesar, could the Gauls unite under a single leader like Vercingetorix. Even then, however, the faction lines were clear.

The Romans divided Gaul broadly into Provincia (the conquered area around the Mediterranean), and the northern Gallia Comata ("free Gaul" or "long haired Gaul"). Caesar divided the people of Gallia Comata into three broad groups: the Aquitani; Galli (who in their own language were called Celtae); and Belgae. In the modern sense, Gaulish peoples are defined linguistically, as speakers of dialects of the Gaulish language. While the Aquitani were probably Vascons, the Belgae would thus probably be a mixture of Celtic and Germanic elements.

Julius Caesar, in his book, The Gallic Wars, comments:

All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in our Gauls, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws. The river Garonne separates the Gauls from the Aquitani; the Marne and the Seine separate them from the Belgae. Of all these, the Belgae are the bravest, because they are furthest from the civilization and refinement of [our] Province, and merchants least frequently resort to them, and import those things which tend to effeminate the mind; and they are the nearest to the Germans, who dwell beyond the Rhine, with whom they are continually waging war; for which reason the Helvetii also surpass the rest of the Gauls in valor, as they contend with the Germans in almost daily battles, when they either repel them from their own territories, or themselves wage war on their frontiers. One part of these, which it has been said that the Gauls occupy, takes its beginning at the river Rhone; it is bounded by the river Garonne, the ocean, and the territories of the Belgae; it borders, too, on the side of the Sequani and the Helvetii, upon the river Rhine, and stretches toward the north. The Belgae rises from the extreme frontier of Gaul, extend to the lower part of the river Rhine; and look toward the north and the rising sun. Aquitania extends from the river Garonne to the Pyrenaean mountains and to that part of the ocean which is near Spain: it looks between the setting of the sun, and the north star. .[40]

Religion[edit]

The Gauls practiced a form of animism, ascribing human characteristics to lakes, streams, mountains, and other natural features and granting them a quasi-divine status. Also, worship of animals was not uncommon; the animal most sacred to the Gauls was the boar[41] which can be found on many Gallic military standards, much like the Roman eagle.

Their system of gods and goddesses was loose, there being certain deities which virtually every Gallic person worshipped, as well as clan and household gods. Many of the major gods were related to Greek gods; the primary god worshipped at the time of the arrival of Caesar was Teutates, the Gallic equivalent of Mercury. The "ancestor god" of the Gauls was identified by Julius Caesar in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico with the Roman god Dis Pater.[42]

Perhaps the most intriguing facet of Gallic religion is the practice of the Druids. The druids presided over human or animal sacrifices that were made in wooded groves or crude temples. They also appear to have held the responsibility for preserving the annual agricultural calendar and instigating seasonal festivals which corresponded to key points of the lunar-solar calendar. The religious practices of druids were syncretic and borrowed from earlier pagan traditions, with probably indo-European roots. Julius Caesar mentions in his Gallic Wars that those Celts who wanted to make a close study of druidism went to Britain to do so. In a little over a century later, Gnaeus Julius Agricola mentions Roman armies attacking a large druid sanctuary in Anglesey in Wales. There is no certainty concerning the origin of the druids, but it is clear that they vehemently guarded the secrets of their order and held sway over the people of Gaul. Indeed, they claimed the right to determine questions of war and peace, and thereby held an "international" status. In addition, the Druids monitored the religion of ordinary Gauls and were in charge of educating the aristocracy. They also practiced a form of excommunication from the assembly of worshippers, which in ancient Gaul meant a separation from secular society as well. Thus the Druids were an important part of Gallic society. The nearly complete and mysterious disappearance of the Celtic language from most of the territorial lands of ancient Gaul, with the exception of Brittany, can be attributed to the fact that Celtic druids refused to allow the Celtic oral literature or traditional wisdom to be committed to the written letter.[43]

See also[edit]

- Ambiorix

- Asterix—a French comic about Gaul and Rome, mainly set in 50 BC

- Bog body

- Braccae—trousers, typical Gallic dress

- Cisalpine Gaul

- Galatia

- Lugdunum

- Roman Republic

- Roman villas in northwestern Gaul

References[edit]

- ^ English: /ˈɡæliə/

- ^ Polybius: Histories

- ^ Arrowsmith, Aaron (1832). A Grammar of Ancient Geography,: Compiled for the Use of King's College School. Hansard London 1832. p. 50. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

gallia .

- ^ Bisdent, Bisdent (28 April 2011). "Gaul". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Birkhan 1997, p. 48.

- ^ "The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville" p. 198 Cambridge University Press 2006 Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach and Oliver Berghof.

- ^ "gallu". Google Translate. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Howlsedhes Services. "Gerlyver Sempel". Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ Pierre-Yves Lambert, La langue gauloise, éditions Errance, 1994, p. 194.

- ^ Ekblom, R., "Die Herkunft des Namens La Gaule" in: Studia Neophilologica, Uppsala, XV, 1942-43, nos. 1-2, p. 291-301.

- ^ Sjögren, Albert, Le nom de "Gaule", in Studia Neophilologica, Vol. 11 (1938/39) pp. 210–214.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (OUP 1966), p. 391.

- ^ Nouveau dictionnaire étymologique et historique (Larousse 1990), p. 336.

- ^ Koch 2006, p. 532.

- ^ Koch 2006, pp. 775–776.

- ^ Gael is derived from Old Irish Goidel (borrowed, in turn, in the 7th century AD from Primitive Welsh Guoidel—spelled Gwyddel in Middle Welsh and Modern Welsh—likely derived from a Brittonic root *Wēdelos meaning literally "forest person, wild man")[15]

- ^ Linehan, Peter; Janet L. Nelson (2003). The Medieval World. 10. Routledge. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-415-30234-0.

- ^ Berresford Ellis, Peter (1998). The Celts: A History. Caroll & Graf. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-7867-1211-2.

- ^ Dietler, Michael (2010). Archaeologies of Colonialism: Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. Berkeley, CA.

- ^ a b Drinkwater 2014, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Drinkwater 2014, p. 6.

- ^ Drinkwater 2014, p. 6. "[...] the most important outcome of this series of campaigns was the direct annexation by Rome of a huge area extending from the Pyrenees to the lower Rhône, and up the Rhône valley to Lake Geneva."

- ^ "France: The Roman conquest". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

Because of chronic internal rivalries, Gallic resistance was easily broken, though Vercingetorix’s Great Rebellion of 52 bc had notable successes.

- ^ "Julius Caesar: The first triumvirate and the conquest of Gaul". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

Indeed, the Gallic cavalry was probably superior to the Roman, horseman for horseman. Rome’s military superiority lay in its mastery of strategy, tactics, discipline, and military engineering. In Gaul, Rome also had the advantage of being able to deal separately with dozens of relatively small, independent, and uncooperative states. Caesar conquered these piecemeal, and the concerted attempt made by a number of them in 52 BC to shake off the Roman yoke came too late.

- ^ Plutarch, Caesar 22.

- ^ Tibbetts, Jann (2016-07-30). 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789385505669.

- ^ Seindal, René (28 August 2003). "Julius Caesar, Romans [The Conquest of Gaul - part 4 of 11] (Photo Archive)". Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ Serghidou, Anastasia (2007). Fear of slaves, fear of enslavement in the ancient Mediterranean. Besançon: Presses Univ. Franche-Comté. p. 50. ISBN 978-2848671697. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ A recent survey is G. Woolf, Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul (Cambridge University Press) 1998.

- ^ Bachrach, Bernard S. (1972). Merovingian Military Organization, 481-751. U of Minnesota Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780816657001.

- ^ Pollini, J. (2002). Gallo-Roman Bronzes and the Process of Romanization: The Cobannus Hoard. Monumenta Graeca et Romana. 9. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Oaks, L.S. (1986). "The goddess Epona: concepts of sovereignty in a changing landscape". Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire.

- ^ a b Laurence Hélix (2011). Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5.

Le déclin du Gaulois et sa disparition ne s'expliquent pas seulement par des pratiques culturelles spécifiques: Lorsque les Romains conduits par César envahirent la Gaule, au 1er siecle avant J.-C., celle-ci romanisa de manière progressive et profonde. Pendant près de 500 ans, la fameuse période gallo-romaine, le gaulois et le latin parlé coexistèrent; au VIe siècle encore; le temoignage de Grégoire de Tours atteste la survivance de la langue gauloise.

- ^ Hist. Franc., book I, 32 Veniens vero Arvernos, delubrum illud, quod Gallica lingua Vasso Galatæ vocant, incendit, diruit, atque subvertit. And coming to Clermont [to the Arverni] he set on fire, overthrew and destroyed that shrine which they call Vasso Galatæ in the Gallic tongue.

- ^ Henri Guiter, "Sur le substrat gaulois dans la Romania", in Munus amicitae. Studia linguistica in honorem Witoldi Manczak septuagenarii, eds., Anna Bochnakowa & Stanislan Widlak, Krakow, 1995.

- ^ Eugeen Roegiest, Vers les sources des langues romanes: Un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania (Leuven, Belgium: Acco, 2006), 83.

- ^ Savignac, Jean-Paul (2004). Dictionnaire Français-Gaulois. Paris: La Différence. p. 26.

- ^ Matasovic, Ranko (2007). "Insular Celtic as a Language Area". Papers from the Workship within the Framework of the XIII International Congress of Celtic Studies. The Celtic Languages in Contact: 106.

- ^ a b c Adams, J. N. (2007). "Chapter V -- Regionalisms in provincial texts: Gaul". The Regional Diversification of Latin 200 BC – AD 600. Cambridge. p. 279–289. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511482977. ISBN 9780511482977.

- ^ Caesar, Julius; McDevitte, W. A.; Bohn, W. S., trans (1869). The Gallic Wars. New York: Harper. p. 9. ISBN 978-1604597622. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ MacCulloch, John Arnott (1911). The Religion of the Ancient Celts. Edinburgh: Clark. p. 22. ISBN 978-1508518518. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Warner, Marina; Burn, Lucilla (2003). World of Myths, Vol. 1. London: British Museum. p. 382. ISBN 978-0714127835. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Kendrick, Thomas D. (1966). The Druids: A study in Keltic prehistory (1966 ed.). New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 78.

Sources[edit]

- Birkhan, H. (1997). Die Kelten. Vienna.

- Drinkwater, John Frederick (2014) [1983]. "Conquest and Pacification". Roman Gaul: The Three Provinces, 58 BC-AD 260. Routledge Revivals. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317750741.

- Koch, John Thomas (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman Gaul. |