La transferencia horizontal de genes ( HGT ) o la transferencia lateral de genes ( LGT ) [1] [2] [3] es el movimiento de material genético entre organismos unicelulares y / o multicelulares que no sea por la transmisión ("vertical") de ADN de un padre a otro. descendencia ( reproducción ). [4] La HGT es un factor importante en la evolución de muchos organismos. [5] [6]

La transferencia horizontal de genes es el mecanismo principal para la propagación de la resistencia a los antibióticos en las bacterias, [5] [7] [8] [9] [10] y desempeña un papel importante en la evolución de las bacterias que pueden degradar compuestos nuevos como los humanos. creado pesticidas [11] y en la evolución, mantenimiento y transmisión de la virulencia . [12] A menudo involucra bacteriófagos y plásmidos templados . [13] [14] [15]Los genes responsables de la resistencia a los antibióticos en una especie de bacteria pueden transferirse a otra especie de bacteria a través de varios mecanismos de HGT como la transformación , transducción y conjugación , y posteriormente armar al receptor de los genes resistentes a los antibióticos contra los antibióticos. La rápida propagación de los genes de resistencia a los antibióticos de esta manera se está volviendo un desafío médico de tratar. Los factores ecológicos también pueden desempeñar un papel en la HGT de los genes resistentes a los antibióticos. [16] También se postula que la HGT promueve el mantenimiento de una bioquímica de vida universal y, posteriormente, la universalidad del código genético. [17]

La mayor parte del pensamiento en genética se ha centrado en la transferencia vertical, pero se empieza a reconocer la importancia de la transferencia horizontal de genes entre organismos unicelulares. [18] [19]

La entrega de genes puede verse como una transferencia de genes horizontal artificial y es una forma de ingeniería genética .

Historia [ editar ]

El experimento de Griffith , reportado en 1928 por Frederick Griffith , [20] fue el primer experimento que sugiere que las bacterias son capaces de transferir información genética a través de un proceso conocido como transformación . [21] [22] Los hallazgos de Griffith fueron seguidos por una investigación a fines de la década de 1930 y principios de la de 1940 que aisló el ADN como el material que comunicaba esta información genética.

La transferencia genética horizontal se describió luego en Seattle en 1951, en un artículo que demostraba que la transferencia de un gen viral a Corynebacterium diphtheriae creaba una cepa virulenta a partir de una cepa no virulenta, [23] también resolviendo simultáneamente el enigma de la difteria (que los pacientes podían infectarse con la bacteria pero no presentar ningún síntoma, y luego convertirse repentinamente más tarde o nunca), [24] y dar el primer ejemplo de la relevancia del ciclo lisogénico . [25] La transferencia de genes interbacterianos se describió por primera vez en Japón en una publicación de 1959 que demostró la transferencia de resistencia a los antibióticos entre diferentes especies de bacterias . [26][27] A mediados de la década de 1980, Syvanen [28] predijo que la transferencia lateral de genes existía, tenía un significado biológico y estaba involucrada en la configuración de la historia evolutiva desde el comienzo de la vida en la Tierra.

Como lo expresaron Jian, Rivera y Lake (1999): "Cada vez más, los estudios de genes y genomas indican que se ha producido una transferencia horizontal considerable entre procariotas " [29] (véase también Lake y Rivera, 2007). [30] El fenómeno parece haber tenido cierta importancia también para los eucariotas unicelulares . Como Bapteste et al. (2005) observan, "evidencia adicional sugiere que la transferencia de genes también podría ser un mecanismo evolutivo importante en la evolución protista ". [31]

El injerto de una planta a otra puede transferir cloroplastos ( orgánulos en las células vegetales que realizan la fotosíntesis ), ADN mitocondrial y el núcleo celular completo que contiene el genoma para potencialmente crear una nueva especie. [32] Algunos lepidópteros (por ejemplo, las mariposas monarca y los gusanos de seda ) se han modificado genéticamente mediante la transferencia horizontal de genes del bracovirus avispa . [33] Las picaduras de insectos de la familia Reduviidae (chinches asesinas) pueden, a través de un parásito, infectar a los humanos con el tripanosomal Enfermedad de Chagas , que puede insertar su ADN en el genoma humano. [34] Se ha sugerido que la transferencia lateral de genes a humanos desde bacterias puede desempeñar un papel en el cáncer. [35]

Aaron Richardson y Jeffrey D. Palmer afirman: "La transferencia horizontal de genes (HGT) ha jugado un papel importante en la evolución bacteriana y es bastante común en ciertos eucariotas unicelulares. Sin embargo, la prevalencia e importancia de HGT en la evolución de eucariotas multicelulares siguen sin estar claras. " [36]

Debido a la creciente cantidad de evidencia que sugiere la importancia de estos fenómenos para la evolución (ver más abajo ), biólogos moleculares como Peter Gogarten han descrito la transferencia horizontal de genes como "Un nuevo paradigma para la biología". [37]

Mecanismos [ editar ]

Existen varios mecanismos para la transferencia horizontal de genes: [5] [38] [39]

- Transformación , la alteración genética de una célula resultante de la introducción, captación y expresión de material genético extraño ( ADN o ARN ). [40] Este proceso es relativamente común en bacterias, pero menos en eucariotas. [41] La transformación se usa a menudo en laboratorios para insertar genes nuevos en bacterias para experimentos o para aplicaciones industriales o médicas. Véase también biología molecular y biotecnología .

- Transducción , el proceso por el cual un virus (un bacteriófago o fago ) mueve el ADN bacteriano de una bacteria a otra . [40]

- Conjugación bacteriana , un proceso que implica la transferencia de ADN a través de un plásmido de una célula donante a una célula receptora recombinante durante el contacto de célula a célula. [40]

- Agentes de transferencia de genes , elementos similares a virus codificados por el huésped que se encuentran en el orden de las alfaproteobacterias Rhodobacterales . [42]

Transferencia de transposón horizontal [ editar ]

Un elemento transponible (TE) (también llamado transposón o gen saltarín) es un segmento móvil de ADN que a veces puede captar un gen de resistencia e insertarlo en un plásmido o cromosoma, induciendo así la transferencia horizontal de genes de resistencia a los antibióticos. [40]

La transferencia horizontal de transposones (HTT) se refiere al paso de fragmentos de ADN que se caracterizan por su capacidad para moverse de un locus a otro entre genomas por medios distintos de la herencia de padres a hijos. Durante mucho tiempo se pensó que la transferencia horizontal de genes era crucial para la evolución procariota, pero hay una cantidad creciente de datos que muestran que la HTT es un fenómeno común y generalizado también en la evolución eucariota . [43] En el lado de los elementos transponibles, la propagación entre genomas a través de la transferencia horizontal puede verse como una estrategia para escapar de la purga debido a la selección purificadora, la desintegración mutacional y / o los mecanismos de defensa del huésped. [44]

HTT puede ocurrir con cualquier tipo de elementos transponibles, pero es más probable que los transposones de ADN y los retroelementos LTR sean capaces de HTT porque ambos tienen un intermedio de ADN bicatenario estable que se piensa que es más resistente que el intermedio de ARN monocatenario de no -Retroelementos LTR , que pueden ser altamente degradables. [43] Es menos probable que los elementos no autónomos se transfieran horizontalmente en comparación con los elementos autónomos porque no codifican las proteínas necesarias para su propia movilización. La estructura de estos elementos no autónomos generalmente consiste en un gen sin intrones que codifica una transposasa.proteína, y puede tener o no una secuencia promotora. Aquellos que no tienen secuencias promotoras codificadas dentro de la región móvil dependen de los promotores del hospedador adyacentes para la expresión. [43] Se cree que la transferencia horizontal juega un papel importante en el ciclo de vida de la ET. [43]

HTT has been shown to occur between species and across continents in both plants[45] and animals (Ivancevic et al. 2013), though some TEs have been shown to more successfully colonize the genomes of certain species over others.[46] Both spatial and taxonomic proximity of species has been proposed to favor HTTs in plants and animals.[45] It is unknown how the density of a population may affect the rate of HTT events within a population, but close proximity due to parasitism and cross contamination due to crowding have been proposed to favor HTT in both plants and animals.[45] Successful transfer of a transposable element requires delivery of DNA from donor to host cell (and to the germ line for multi-cellular organisms), followed by integration into the recipient host genome.[43] Though the actual mechanism for the transportation of TEs from donor cells to host cells is unknown, it is established that naked DNA and RNA can circulate in bodily fluid.[43] Many proposed vectors include arthropods, viruses, freshwater snails (Ivancevic et al. 2013), endosymbiotic bacteria,[44] and intracellular parasitic bacteria.[43] In some cases, even TEs facilitate transport for other TEs.[46]

The arrival of a new TE in a host genome can have detrimental consequences because TE mobility may induce mutation. However, HTT can also be beneficial by introducing new genetic material into a genome and promoting the shuffling of genes and TE domains among hosts, which can be co-opted by the host genome to perform new functions.[46] Moreover, transposition activity increases the TE copy number and generates chromosomal rearrangement hotspots.[47] HTT detection is a difficult task because it is an ongoing phenomenon that is constantly changing in frequency of occurrence and composition of TEs inside host genomes. Furthermore, few species have been analyzed for HTT, making it difficult to establish patterns of HTT events between species. These issues can lead to the underestimation or overestimation of HTT events between ancestral and current eukaryotic species.[47]

Methods of detection[edit]

Horizontal gene transfer is typically inferred using bioinformatics methods, either by identifying atypical sequence signatures ("parametric" methods) or by identifying strong discrepancies between the evolutionary history of particular sequences compared to that of their hosts. The transferred gene (xenolog) found in the receiving species is more closely related to the genes of the donor species than would be expected.

Viruses[edit]

The virus called Mimivirus infects amoebae. Another virus, called Sputnik, also infects amoebae, but it cannot reproduce unless mimivirus has already infected the same cell.[48] "Sputnik's genome reveals further insight into its biology. Although 13 of its genes show little similarity to any other known genes, three are closely related to mimivirus and mamavirus genes, perhaps cannibalized by the tiny virus as it packaged up particles sometime in its history. This suggests that the satellite virus could perform horizontal gene transfer between viruses, paralleling the way that bacteriophages ferry genes between bacteria."[49] Horizontal transfer is also seen between geminiviruses and tobacco plants.[50]

Prokaryotes[edit]

Horizontal gene transfer is common among bacteria, even among very distantly related ones. This process is thought to be a significant cause of increased drug resistance[5][51] when one bacterial cell acquires resistance, and the resistance genes are transferred to other species.[52][53] Transposition and horizontal gene transfer, along with strong natural selective forces have led to multi-drug resistant strains of S. aureus and many other pathogenic bacteria.[40] Horizontal gene transfer also plays a role in the spread of virulence factors, such as exotoxins and exoenzymes, amongst bacteria.[5] A prime example concerning the spread of exotoxins is the adaptive evolution of Shiga toxins in E. coli through horizontal gene transfer via transduction with Shigella species of bacteria.[54] Strategies to combat certain bacterial infections by targeting these specific virulence factors and mobile genetic elements have been proposed.[12] For example, horizontally transferred genetic elements play important roles in the virulence of E. coli, Salmonella, Streptococcus and Clostridium perfringens.[5]

In prokaryotes, restriction-modification systems are known to provide immunity against horizontal gene transfer and in stabilizing mobile genetic elements. Genes encoding restriction modification systems have been reported to move between prokaryotic genomes within mobile genetic elements (MGE) such as plasmids, prophages, insertion sequences/transposons, integrative conjugative elements (ICE),[55] and integrons. Still, they are more frequently a chromosomal-encoded barrier to MGE than an MGE-encoded tool for cell infection.[56]

Lateral gene transfer via a mobile genetic element, namely the integrated conjugative element (ICE) Bs1 has been reported for its role in the global DNA damage SOS response of the gram positive Bacillus subtilis.[57] Furthermore it has been linked with the radiation and desiccation resistance of Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032 spores,[58] isolated from spacecraft cleanroom facilities.[59][60][61]

Transposon insertion elements have been reported to increase the fitness of gram-negative E. coli strains through either major transpositions or genome rearrangements, and increasing mutation rates.[62][63] In a study on the effects of long-term exposure of simulated microgravity on non-pathogenic E. coli, the results showed transposon insertions occur at loci, linked to SOS stress response.[64] When the same E. coli strain was exposed to a combination of simulated microgravity and trace (background) levels of (the broad spectrum) antibiotic (chloramphenicol), the results showed transposon-mediated rearrangements (TMRs), disrupting genes involved in bacterial adhesion, and deleting an entire segment of several genes involved with motility and chemotaxis.[65] Both these studies have implications for microbial growth, adaptation to and antibiotic resistance in real time space conditions.

Bacterial transformation[edit]

Natural transformation is a bacterial adaptation for DNA transfer (HGT) that depends on the expression of numerous bacterial genes whose products are responsible for this process.[66][67] In general, transformation is a complex, energy-requiring developmental process. In order for a bacterium to bind, take up and recombine exogenous DNA into its chromosome, it must become competent, that is, enter a special physiological state. Competence development in Bacillus subtilis requires expression of about 40 genes.[68] The DNA integrated into the host chromosome is usually (but with infrequent exceptions) derived from another bacterium of the same species, and is thus homologous to the resident chromosome. The capacity for natural transformation occurs in at least 67 prokaryotic species.[67]Competence for transformation is typically induced by high cell density and/or nutritional limitation, conditions associated with the stationary phase of bacterial growth. Competence appears to be an adaptation for DNA repair.[69] Transformation in bacteria can be viewed as a primitive sexual process, since it involves interaction of homologous DNA from two individuals to form recombinant DNA that is passed on to succeeding generations. Although transduction is the form of HGT most commonly associated with bacteriophages, certain phages may also be able to promote transformation.[70]

Bacterial conjugation[edit]

Conjugation in Mycobacterium smegmatis, like conjugation in E. coli, requires stable and extended contact between a donor and a recipient strain, is DNase resistant, and the transferred DNA is incorporated into the recipient chromosome by homologous recombination. However, unlike E. coli high frequency of recombination conjugation (Hfr), mycobacterial conjugation is a type of HGT that is chromosome rather than plasmid based.[71] Furthermore, in contrast to E. coli (Hfr) conjugation, in M. smegmatis all regions of the chromosome are transferred with comparable efficiencies. Substantial blending of the parental genomes was found as a result of conjugation, and this blending was regarded as reminiscent of that seen in the meiotic products of sexual reproduction.[71][72]

Archaeal DNA transfer[edit]

The archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus, when UV irradiated, strongly induces the formation of type IV pili which then facilitates cellular aggregation.[73][74] Exposure to chemical agents that cause DNA damage also induces cellular aggregation.[73] Other physical stressors, such as temperature shift or pH, do not induce aggregation, suggesting that DNA damage is a specific inducer of cellular aggregation.

UV-induced cellular aggregation mediates intercellular chromosomal HGT marker exchange with high frequency,[75] and UV-induced cultures display recombination rates that exceed those of uninduced cultures by as much as three orders of magnitude. S. solfataricus cells aggregate preferentially with other cells of their own species.[75] Frols et al.[73][76] and Ajon et al.[75] suggested that UV-inducible DNA transfer is likely an important mechanism for providing increased repair of damaged DNA via homologous recombination. This process can be regarded as a simple form of sexual interaction.

Another thermophilic species, Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, is able to undergo HGT. S. acidocaldarius can exchange and recombine chromosomal markers at temperatures up to 84 °C.[77] UV exposure induces pili formation and cellular aggregation.[75] Cells with the ability to aggregate have greater survival than mutants lacking pili that are unable to aggregate. The frequency of recombination is increased by DNA damage induced by UV-irradiation[78] and by DNA damaging chemicals.[79]

The ups operon, containing five genes, is highly induced by UV irradiation. The proteins encoded by the ups operon are employed in UV-induced pili assembly and cellular aggregation leading to intercellular DNA exchange and homologous recombination.[80] Since this system increases the fitness of S. acidocaldarius cells after UV exposure, Wolferen et al.[80][81] considered that transfer of DNA likely takes place in order to repair UV-induced DNA damages by homologous recombination.

Eukaryotes[edit]

"Sequence comparisons suggest recent horizontal transfer of many genes among diverse species including across the boundaries of phylogenetic 'domains'. Thus determining the phylogenetic history of a species can not be done conclusively by determining evolutionary trees for single genes."[82]

Organelle to nuclear genome[edit]

- Analysis of DNA sequences suggests that horizontal gene transfer has occurred within eukaryotes from the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes to the nuclear genome. As stated in the endosymbiotic theory, chloroplasts and mitochondria probably originated as bacterial endosymbionts of a progenitor to the eukaryotic cell.[83]

Organelle to organelle[edit]

- Mitochondrial genes moved to parasites of the Rafflesiaceae plant family from their hosts[84][85] and from chloroplasts of a still-unidentified plant to the mitochondria of the bean Phaseolus.[86]

Viruses to plants[edit]

- Plants are capable of receiving genetic information from viruses by horizontal gene transfer.[50]

Bacteria to fungi[edit]

- Horizontal transfer occurs from bacteria to some fungi, such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.[87]

Bacteria to plants[edit]

- Agrobacterium, a pathogenic bacterium that causes cells to proliferate as crown galls and proliferating roots is an example of a bacterium that can transfer genes to plants and this plays an important role in plant evolution.[88]

Bacteria to insects[edit]

- HhMAN1 is a gene in the genome of the coffee borer beetle (Hypothenemus hampei) that resembles bacterial genes, and is thought to be transferred from bacteria in the beetle's gut.[89][90]

Bacteria to animals[edit]

- Bdelloid rotifers currently hold the 'record' for HGT in animals with ~8% of their genes from bacterial origins.[91] Tardigrades were thought to break the record with 17.5% HGT, but that finding was an artifact of bacterial contamination.[92]

- A study found the genomes of 40 animals (including 10 primates, four Caenorhabditis worms, and 12 Drosophila insects) contained genes which the researchers concluded had been transferred from bacteria and fungi by horizontal gene transfer.[93] The researchers estimated that for some nematodes and Drosophila insects these genes had been acquired relatively recently.[94]

- A bacteriophage-mediated mechanism transfers genes between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nuclear localization signals in bacteriophage terminal proteins (TP) prime DNA replication and become covalently linked to the viral genome. The role of virus and bacteriophages in HGT in bacteria, suggests that TP-containing genomes could be a vehicle of inter-kingdom genetic information transference all throughout evolution.[95]

Endosymbiont to insects and nematodes[edit]

- The adzuki bean beetle has acquired genetic material from its (non-beneficial) endosymbiont Wolbachia.[96] New examples have recently been reported demonstrating that Wolbachia bacteria represent an important potential source of genetic material in arthropods and filarial nematodes.[97]

Plant to plant[edit]

- Striga hermonthica, a parasitic eudicot, has received a gene from sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) to its nuclear genome.[98] The gene's functionality is unknown.

- A gene that allowed ferns to survive in dark forests came from the hornwort, which grows in mats on streambanks or trees. The neochrome gene arrived about 180 million years ago.[99]

Plants to animals[edit]

- The eastern emerald sea slug Elysia chlorotica has been suggested by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis to contain photosynthesis-supporting genes obtained from an algae (Vaucheria litorea) in their diet.[100] LGT in Sacoglossa is now thought to be an artifact[101] and no trace of LGT was found upon sequencing the genome of Elysia chlorotica.[102]

Plant to fungus[edit]

- Gene transfer between plants and fungi has been posited for a number of cases, including rice (Oryza sativa).

Fungi to insects[edit]

- Pea aphids (Acyrthosiphon pisum) contain multiple genes from fungi.[103][104] Plants, fungi, and microorganisms can synthesize carotenoids, but torulene made by pea aphids is the only carotenoid known to be synthesized by an organism in the animal kingdom.[103]

Human to protozoan[edit]

- The malaria pathogen Plasmodium vivax acquired genetic material from humans that might help facilitate its long stay in the body.[105]

Human genome[edit]

- One study identified approximately 100 of humans' approximately 20,000 total genes which likely resulted from horizontal gene transfer,[106] but this number has been challenged by several researchers arguing these candidate genes for HGT are more likely the result of gene loss combined with differences in the rate of evolution.[107]

Artificial horizontal gene transfer[edit]

Genetic engineering is essentially horizontal gene transfer, albeit with synthetic expression cassettes. The Sleeping Beauty transposon system[108] (SB) was developed as a synthetic gene transfer agent that was based on the known abilities of Tc1/mariner transposons to invade genomes of extremely diverse species.[109] The SB system has been used to introduce genetic sequences into a wide variety of animal genomes.[110][111] (See also Gene therapy.)

Importance in evolution[edit]

Horizontal gene transfer is a potential confounding factor in inferring phylogenetic trees based on the sequence of one gene.[112] For example, given two distantly related bacteria that have exchanged a gene a phylogenetic tree including those species will show them to be closely related because that gene is the same even though most other genes are dissimilar. For this reason, it is often ideal to use other information to infer robust phylogenies such as the presence or absence of genes or, more commonly, to include as wide a range of genes for phylogenetic analysis as possible.

For example, the most common gene to be used for constructing phylogenetic relationships in prokaryotes is the 16S ribosomal RNA gene since its sequences tend to be conserved among members with close phylogenetic distances, but variable enough that differences can be measured. However, in recent years it has also been argued that 16s rRNA genes can also be horizontally transferred. Although this may be infrequent, the validity of 16s rRNA-constructed phylogenetic trees must be reevaluated.[113]

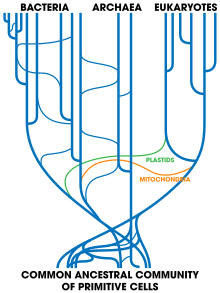

Biologist Johann Peter Gogarten suggests "the original metaphor of a tree no longer fits the data from recent genome research" therefore "biologists should use the metaphor of a mosaic to describe the different histories combined in individual genomes and use the metaphor of a net to visualize the rich exchange and cooperative effects of HGT among microbes".[37] There exist several methods to infer such phylogenetic networks.

Using single genes as phylogenetic markers, it is difficult to trace organismal phylogeny in the presence of horizontal gene transfer. Combining the simple coalescence model of cladogenesis with rare HGT horizontal gene transfer events suggest there was no single most recent common ancestor that contained all of the genes ancestral to those shared among the three domains of life. Each contemporary molecule has its own history and traces back to an individual molecule cenancestor. However, these molecular ancestors were likely to be present in different organisms at different times."[114]

Challenge to the tree of life[edit]

Horizontal gene transfer poses a possible challenge to the concept of the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) at the root of the tree of life first formulated by Carl Woese, which led him to propose the Archaea as a third domain of life.[115] Indeed, it was while examining the new three-domain view of life that horizontal gene transfer arose as a complicating issue: Archaeoglobus fulgidus was seen as an anomaly with respect to a phylogenetic tree based upon the encoding for the enzyme HMGCoA reductase—the organism in question is a definite Archaean, with all the cell lipids and transcription machinery that are expected of an Archaean, but whose HMGCoA genes are of bacterial origin.[115] Scientists are broadly agreed on symbiogenesis, that mitochondria in eukaryotes derived from alpha-proteobacterial cells and that chloroplasts came from ingested cyanobacteria, and other gene transfers may have affected early eukaryotes. (In contrast, multicellular eukaryotes have mechanisms to prevent horizontal gene transfer, including separated germ cells.) If there had been continued and extensive gene transfer, there would be a complex network with many ancestors, instead of a tree of life with sharply delineated lineages leading back to a LUCA.[115][116] However, a LUCA can be identified, so horizontal transfers must have been relatively limited.[117]

Phylogenetic information in HGT[edit]

It has been remarked that, despite the complications, the detection of horizontal gene transfers brings valuable phylogenetic and dating information.[118]

The potential of HGT to be used for dating phylogenies has recently been confirmed.[119][120]

The chromosomal organization of horizontal gene transfer[edit]

The acquisition of new genes has the potential to disorganize the other genetic elements and hinder the function of the bacterial cell, thus affecting the competitiveness of bacteria. Consequently, bacterial adaptation lies in a conflict between the advantages of acquiring beneficial genes, and the need to maintain the organization of the rest of its genome. Horizontally transferred genes are typically concentrated in only ~1% of the chromosome (in regions called hotspots). This concentration increases with genome size and with the rate of transfer. Hotspots diversify by rapid gene turnover; their chromosomal distribution depends on local contexts (neighboring core genes), and content in mobile genetic elements. Hotspots concentrate most changes in gene repertoires, reduce the trade-off between genome diversification and organization, and should be treasure troves of strain-specific adaptive genes. Most mobile genetic elements and antibiotic resistance genes are in hotspots, but many hotspots lack recognizable mobile genetic elements and exhibit frequent homologous recombination at flanking core genes. Overrepresentation of hotspots with fewer mobile genetic elements in naturally transformable bacteria suggests that homologous recombination and horizontal gene transfer are tightly linked in genome evolution.[121]

Genes[edit]

There is evidence for historical horizontal transfer of the following genes:

- Lycopene cyclase for carotenoid biosynthesis, between Chlorobi and Cyanobacteria.[122]

- TetO gene conferring resistance to tetracycline, between Campylobacter jejuni.[123]

- Neochrome, a gene in some ferns that enhances their ability to survive in dim light. Believed to have been acquired from algae sometime during the Cretaceous.[124][125]

- Transfer of a cysteine synthase from a bacterium into phytophagous mites and Lepidoptera allowing the detoxification of cyanogenic glucosides produced by host plants.[126]

- The LINE1 sequence has transferred from humans to the gonorrhea bacteria.[127]

See also[edit]

- Agrobacterium, a bacterium well known for its ability to transfer DNA between itself and plants.

- Endogenous retrovirus

- Genetically modified organism

- Inferring horizontal gene transfer

- Integron

- Mobile genetic elements

- Phylogenetic network

- Phylogenetic tree

- Provirus

- Reassortment

- Retrotransposon

- Symbiogenesis

- Tree of life (biology)

- Xenobiology

References[edit]

- ^ Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA (May 2000). "Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation". Nature. 405 (6784): 299–304. Bibcode:2000Natur.405..299O. doi:10.1038/35012500. PMID 10830951. S2CID 85739173.

- ^ Dunning Hotopp JC (April 2011). "Horizontal gene transfer between bacteria and animals". Trends in Genetics. 27 (4): 157–63. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2011.01.005. PMC 3068243. PMID 21334091.

- ^ Robinson KM, Sieber KB, Dunning Hotopp JC (October 2013). "A review of bacteria-animal lateral gene transfer may inform our understanding of diseases like cancer". PLOS Genetics. 9 (10): e1003877. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003877. PMC 3798261. PMID 24146634.

- ^ Keeling PJ, Palmer JD (August 2008). "Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotic evolution". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 9 (8): 605–18. doi:10.1038/nrg2386. PMID 18591983. S2CID 213613.

- ^ a b c d e f Gyles C, Boerlin P (March 2014). "Horizontally transferred genetic elements and their role in pathogenesis of bacterial disease". Veterinary Pathology. 51 (2): 328–40. doi:10.1177/0300985813511131. PMID 24318976. S2CID 206510894.

- ^ Vaux F, Trewick SA, Morgan-Richards M (2017). "Speciation through the looking-glass". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 120 (2): 480–488. doi:10.1111/bij.12872.

- ^ OECD, Safety Assessment of Transgenic Organisms, Volume 4: OECD Consensus Documents, 2010, pp.171-174

- ^ Kay E, Vogel TM, Bertolla F, Nalin R, Simonet P (July 2002). "In situ transfer of antibiotic resistance genes from transgenic (transplastomic) tobacco plants to bacteria". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 68 (7): 3345–51. doi:10.1128/aem.68.7.3345-3351.2002. PMC 126776. PMID 12089013.

- ^ Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Aravind L (2001). "Horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes: quantification and classification". Annual Review of Microbiology. 55 (1): 709–42. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.709. PMC 4781227. PMID 11544372.

- ^ Nielsen KM (1998). "Barriers to horizontal gene transfer by natural transformation in soil bacteria". APMIS. 84 (S84): 77–84. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.1998.tb05653.x. PMID 9850687.

- ^ McGowan C, Fulthorpe R, Wright A, Tiedje JM (October 1998). "Evidence for interspecies gene transfer in the evolution of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid degraders". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 64 (10): 4089–92. doi:10.1128/AEM.64.10.4089-4092.1998. PMC 106609. PMID 9758850.

- ^ a b Keen EC (December 2012). "Paradigms of pathogenesis: targeting the mobile genetic elements of disease". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2: 161. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00161. PMC 3522046. PMID 23248780.

- ^ Naik GA, Bhat LN, Chpoade BA, Lynch JM (1994). "Transfer of broad-host-range antibiotic resistance plasmids in soil microcosms". Curr. Microbiol. 28 (4): 209–215. doi:10.1007/BF01575963. S2CID 21015053.

- ^ Varga M, Kuntová L, Pantůček R, Mašlaňová I, Růžičková V, Doškař J (July 2012). "Efficient transfer of antibiotic resistance plasmids by transduction within methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 clone". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 332 (2): 146–52. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02589.x. PMID 22553940.

- ^ Varga M, Pantu Ček R, Ru Žičková V, Doškař J (January 2016). "Molecular characterization of a new efficiently transducing bacteriophage identified in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus". The Journal of General Virology. 97 (1): 258–268. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000329. PMID 26537974.

- ^ Cairns J, Ruokolainen L, Hultman J, Tamminen M, Virta M, Hiltunen T (2018-04-19). "Ecology determines how low antibiotic concentration impacts community composition and horizontal transfer of resistance genes". Communications Biology. 1 (1): 35. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0041-7. PMC 6123812. PMID 30271921.

- ^ Kubyshkin V, Acevedo-Rocha CG, Budisa N (February 2018). "On universal coding events in protein biogenesis". Bio Systems. 164: 16–25. doi:10.1016/j.biosystems.2017.10.004. PMID 29030023.

- ^ Lin Edwards (October 4, 2010). "Horizontal gene transfer in microbes much more frequent than previously thought". PhysOrg.com. Retrieved 2012-01-06.

- ^ Arnold C (April 2011). "To share and share alike". Scientific American. 304 (4): 30–1. Bibcode:2011SciAm.304d..30A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0411-30. PMID 21495477.

- ^ Griffith F (January 1928). "The Significance of Pneumococcal Types". The Journal of Hygiene. Cambridge University Press. 27 (2): 113–59. doi:10.1017/S0022172400031879. JSTOR 4626734. PMC 2167760. PMID 20474956.

- ^ Lorenz MG, Wackernagel W (September 1994). "Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment". Microbiological Reviews. 58 (3): 563–602. doi:10.1128/MMBR.58.3.563-602.1994. PMC 372978. PMID 7968924.

- ^ Downie AW (November 1972). "Pneumococcal transformation--a backward view. Fourth Griffith Memorial Lecture" (PDF). Journal of General Microbiology. 73 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1099/00221287-73-1-1. PMID 4143929.

- ^ Freeman VJ (June 1951). "Studies on the virulence of bacteriophage-infected strains of Corynebacterium diphtheriae". Journal of Bacteriology. 61 (6): 675–88. doi:10.1128/JB.61.6.675-688.1951. PMC 386063. PMID 14850426.

- ^ Phillip Marguilies "Epidemics: Deadly diseases throughout history". Rosen, New York. 2005.

- ^ André Lwoff (1965). "Interaction among Virus, Cell, and Organism". Nobel Lecture for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

- ^ Ochiai K, Yamanaka T, Kimura K, Sawada O (1959). "Inheritance of drug resistance (and its transfer) between Shigella strains and Between Shigella and E. coli strains". Hihon Iji Shimpor (in Japanese). 1861: 34.

- ^ Akiba T, Koyama K, Ishiki Y, Kimura S, Fukushima T (April 1960). "On the mechanism of the development of multiple-drug-resistant clones of Shigella". Japanese Journal of Microbiology. 4 (2): 219–27. doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.1960.tb00170.x. PMID 13681921.

- ^ Syvanen M (January 1985). "Cross-species gene transfer; implications for a new theory of evolution" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology. 112 (2): 333–43. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(85)80291-5. PMID 2984477.

- ^ Jain R, Rivera MC, Lake JA (March 1999). "Horizontal gene transfer among genomes: the complexity hypothesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (7): 3801–6. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.3801J. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.3801. PMC 22375. PMID 10097118.

- ^ Rivera MC, Lake JA (September 2004). "The ring of life provides evidence for a genome fusion origin of eukaryotes" (PDF). Nature. 431 (7005): 152–5. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..152R. doi:10.1038/nature02848. PMID 15356622. S2CID 4349149. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- ^ Bapteste E, Susko E, Leigh J, MacLeod D, Charlebois RL, Doolittle WF (May 2005). "Do orthologous gene phylogenies really support tree-thinking?". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 5 (1): 33. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-5-33. PMC 1156881. PMID 15913459.

- ^ Le Page M (2016-03-17). "Farmers may have been accidentally making GMOs for millennia". The New Scientist. Retrieved 2016-07-11.

- ^ Gasmi L, Boulain H, Gauthier J, Hua-Van A, Musset K, Jakubowska AK, et al. (September 2015). "Recurrent Domestication by Lepidoptera of Genes from Their Parasites Mediated by Bracoviruses". PLOS Genetics. 11 (9): e1005470. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005470. PMC 4574769. PMID 26379286.

- ^ Yong E (2010-02-14). "Genes from Chagas parasite can transfer to humans and be passed on to children". National Geographic. Retrieved 2016-07-13.

- ^ Riley DR, Sieber KB, Robinson KM, White JR, Ganesan A, Nourbakhsh S, Dunning Hotopp JC (2013). "Bacteria-human somatic cell lateral gene transfer is enriched in cancer samples". PLOS Computational Biology. 9 (6): e1003107. Bibcode:2013PLSCB...9E3107R. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003107. PMC 3688693. PMID 23840181.

- ^ Richardson AO, Palmer JD (2007). "Horizontal gene transfer in plants" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Botany. 58 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1093/jxb/erl148. PMID 17030541. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- ^ a b Gogarten, Peter (2000). "Horizontal Gene Transfer: A New Paradigm for Biology". Esalen Center for Theory and Research Conference. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ Kenneth Todar. "Bacterial Resistance to Antibiotics". The Microbial World: Lectures in Microbiology, Department of Bacteriology, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Archived from the original on January 15, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ Stanley Maloy (July 15, 2002). "Horizontal Gene Transfer". San Diego State University. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Stearns, S. C., & Hoekstra, R. F. (2005). Evolution: An introduction (2nd ed.). Oxford, NY: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 38-40.

- ^ Renner SS, Bellot S (2012). "Horizontal Gene Transfer in Eukaryotes: Fungi-to-Plant and Plant-to-Plant Transfers of Organellar DNA". Genomics of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. 35. Springer Science+Business Media B.V. pp. 223–235. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2920-9_10. ISBN 978-94-007-2919-3.

- ^ Maxmen A (2010). "Virus-like particles speed bacterial evolution". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2010.507.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schaack S, Gilbert C, Feschotte C (September 2010). "Promiscuous DNA: horizontal transfer of transposable elements and why it matters for eukaryotic evolution". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 25 (9): 537–46. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2010.06.001. PMC 2940939. PMID 20591532.

- ^ a b Dupeyron M, Leclercq S, Cerveau N, Bouchon D, Gilbert C (January 2014). "Horizontal transfer of transposons between and within crustaceans and insects". Mobile DNA. 5 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/1759-8753-5-4. PMC 3922705. PMID 24472097.

- ^ a b c El Baidouri M, Carpentier MC, Cooke R, Gao D, Lasserre E, Llauro C, et al. (May 2014). "Widespread and frequent horizontal transfers of transposable elements in plants". Genome Research. 24 (5): 831–8. doi:10.1101/gr.164400.113. PMC 4009612. PMID 24518071.

- ^ a b c Ivancevic AM, Walsh AM, Kortschak RD, Adelson DL (December 2013). "Jumping the fine LINE between species: horizontal transfer of transposable elements in animals catalyses genome evolution". BioEssays. 35 (12): 1071–82. doi:10.1002/bies.201300072. PMID 24003001.

- ^ a b Wallau GL, Ortiz MF, Loreto EL (2012). "Horizontal transposon transfer in eukarya: detection, bias, and perspectives". Genome Biology and Evolution. 4 (8): 689–99. doi:10.1093/gbe/evs055. PMC 3516303. PMID 22798449.

- ^ La Scola B, Desnues C, Pagnier I, Robert C, Barrassi L, Fournous G, et al. (September 2008). "The virophage as a unique parasite of the giant mimivirus". Nature. 455 (7209): 100–4. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..100L. doi:10.1038/nature07218. PMID 18690211. S2CID 4422249.

- ^ Pearson H (August 2008). "'Virophage' suggests viruses are alive". Nature. 454 (7205): 677. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..677P. doi:10.1038/454677a. PMID 18685665.

- ^ a b Bejarano ER, Khashoggi A, Witty M, Lichtenstein C (January 1996). "Integration of multiple repeats of geminiviral DNA into the nuclear genome of tobacco during evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (2): 759–64. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93..759B. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.2.759. PMC 40128. PMID 8570630.

- ^ Barlow M (2009). "What antimicrobial resistance has taught us about horizontal gene transfer". Horizontal Gene Transfer. Methods in Molecular Biology. 532. pp. 397–411. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-853-9_23. ISBN 978-1-60327-852-2. PMID 19271198.

- ^ Hawkey PM, Jones AM (September 2009). "The changing epidemiology of resistance". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 64 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): i3-10. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp256. PMID 19675017.

- ^ Francino MP, ed. (2012). Horizontal Gene Transfer in Microorganisms. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-908230-10-2.

- ^ Strauch E, Lurz R, Beutin L (December 2001). "Characterization of a Shiga toxin-encoding temperate bacteriophage of Shigella sonnei". Infection and Immunity. 69 (12): 7588–95. doi:10.1128/IAI.69.12.7588-7595.2001. PMC 98851. PMID 11705937.

- ^ Johnson CM, Grossman AD (November 2015). "Integrative and Conjugative Elements (ICEs): What They Do and How They Work". Annual Review of Genetics. 42 (1): 577–601. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-112414-055018. PMC 5180612. PMID 26473380.

- ^ Oliveira PH, Touchon M, Rocha EP (September 2014). "The interplay of restriction-modification systems with mobile genetic elements and their prokaryotic hosts". Nucleic Acids Research. 49 (16): 10618–10631. doi:10.1093/nar/gku734. PMC 4176335. PMID 25120263.

- ^ Auchtung JM, Lee CA, Garrison KL, Grossman AD (June 2007). "Identification and characterization of the immunity repressor (ImmR) that controls the mobile genetic element ICE Bs1 of Bacillus subtilis". PLoS Genet. 64 (6): 1515–1528. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05748.x. PMC 3320793. PMID 17511812.

- ^ Tirumalai MR, Fox GE (September 2013). "An ICEBs1-like element may be associated with the extreme radiation and desiccation resistance of Bacillus pumilus SAFR-032 spores". Extremophiles. 17 (5): 767–774. doi:10.1007/s00792-013-0559-z. PMID 23812891.

- ^ Link L, Sawyer J, Venkateswaran K, Nicholson W (February 2004). "Extreme spore UV resistance of Bacillus pumilus isolates obtained from an ultraclean Spacecraft Assembly Facility". Microb Ecol. 47 (2): 159–163. doi:10.1007/s00248-003-1029-4. PMID 14502417.

- ^ Newcombe DA, Schuerger AC, Benardini JN, Dickinson D, Tanner R, Venkateswaran K (December 2005). "Survival of spacecraft-associated microorganisms under simulated martian UV irradiation". Appl Environ Microbiol. 71 (12): 8147–8156. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.12.8147-8156.2005. PMC 1317311. PMID 16332797.

- ^ Kempf MJ, Chen F, Kern R, Venkateswaran K (June 2005). "Recurrent isolation of hydrogen peroxide-resistant spores of Bacillus pumilus from a spacecraft assembly facility". Astrobiology. 5 (3): 391–405. doi:10.1089/ast.2005.5.391. PMID 15941382.

- ^ Biel SW, Hartl DL (June 1983). "Evolution of transposons: natural selection for Tn5 in Escherichia coli K12". Genetics. 103 (4): 581–592. PMC 1202041. PMID 6303898.

- ^ Chao L, Vargas C, Spear BB, Cox EC (1983). "Transposable elements as mutator genes in evolution". Nature. 303 (5918): 633–635. doi:10.1038/303633a0. PMC 1202041. PMID 6303898.

- ^ Tirumalai MR, Karouia F, Tran Q, Stepanov VG, Bruce RJ, Ott M, Pierson DL, Fox GE (May 2017). "The adaptation of Escherichia coli cells grown in simulated microgravity for an extended period is both phenotypic and genomic". npj Microgravity. 3 (15). doi:10.1038/s41526-017-0020-1. PMC 5460176. PMID 28649637.

- ^ Tirumalai MR, Karouia F, Tran Q, Stepanov VG, Bruce RJ, Ott M, Pierson DL, Fox GE (January 2019). "Evaluation of acquired antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli exposed to long-term low-shear modeled microgravity and background antibiotic exposure". mBio. 10 (e02637-18). doi:10.1128/mBio.02637-18. PMC 6336426. PMID 30647159.

- ^ Chen I, Dubnau D (March 2004). "DNA uptake during bacterial transformation". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 2 (3): 241–9. doi:10.1038/nrmicro844. PMID 15083159. S2CID 205499369.

- ^ a b Johnsborg O, Eldholm V, Håvarstein LS (December 2007). "Natural genetic transformation: prevalence, mechanisms and function". Research in Microbiology. 158 (10): 767–78. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2007.09.004. PMID 17997281.

- ^ Solomon JM, Grossman AD (April 1996). "Who's competent and when: regulation of natural genetic competence in bacteria". Trends in Genetics. 12 (4): 150–5. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(96)10014-7. PMID 8901420.

- ^ Michod RE, Bernstein H, Nedelcu AM (May 2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens" (PDF). Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–85. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550.

- ^ Keen EC, Bliskovsky VV, Malagon F, Baker JD, Prince JS, Klaus JS, Adhya SL (January 2017). "Novel "Superspreader" Bacteriophages Promote Horizontal Gene Transfer by Transformation". mBio. 8 (1): e02115-16. doi:10.1128/mBio.02115-16. PMC 5241400. PMID 28096488.

- ^ a b Gray TA, Krywy JA, Harold J, Palumbo MJ, Derbyshire KM (July 2013). "Distributive conjugal transfer in mycobacteria generates progeny with meiotic-like genome-wide mosaicism, allowing mapping of a mating identity locus". PLOS Biology. 11 (7): e1001602. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001602. PMC 3706393. PMID 23874149.

- ^ Derbyshire KM, Gray TA (2014). "Distributive Conjugal Transfer: New Insights into Horizontal Gene Transfer and Genetic Exchange in Mycobacteria". Microbiology Spectrum. 2 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0022-2013. PMC 4259119. PMID 25505644.

- ^ a b c Fröls S, Ajon M, Wagner M, Teichmann D, Zolghadr B, Folea M, et al. (November 2008). "UV-inducible cellular aggregation of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus is mediated by pili formation" (PDF). Molecular Microbiology. 70 (4): 938–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06459.x. PMID 18990182.

- ^ Allers T (November 2011). "Swapping genes to survive - a new role for archaeal type IV pili". Molecular Microbiology. 82 (4): 789–91. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07860.x. PMID 21992544.

- ^ a b c d Ajon M, Fröls S, van Wolferen M, Stoecker K, Teichmann D, Driessen AJ, et al. (November 2011). "UV-inducible DNA exchange in hyperthermophilic archaea mediated by type IV pili" (PDF). Molecular Microbiology. 82 (4): 807–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07861.x. PMID 21999488.

- ^ Fröls S, White MF, Schleper C (February 2009). "Reactions to UV damage in the model archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus". Biochemical Society Transactions. 37 (Pt 1): 36–41. doi:10.1042/BST0370036. PMID 19143598.

- ^ Grogan DW (June 1996). "Exchange of genetic markers at extremely high temperatures in the archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius". Journal of Bacteriology. 178 (11): 3207–11. doi:10.1128/jb.178.11.3207-3211.1996. PMC 178072. PMID 8655500.

- ^ Wood ER, Ghané F, Grogan DW (September 1997). "Genetic responses of the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius to short-wavelength UV light". Journal of Bacteriology. 179 (18): 5693–8. doi:10.1128/jb.179.18.5693-5698.1997. PMC 179455. PMID 9294423.

- ^ Reilly MS, Grogan DW (February 2002). "Biological effects of DNA damage in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 208 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1016/s0378-1097(01)00575-4. PMID 11934490.

- ^ a b van Wolferen M, Ajon M, Driessen AJ, Albers SV (December 2013). "Molecular analysis of the UV-inducible pili operon from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius". MicrobiologyOpen. 2 (6): 928–37. doi:10.1002/mbo3.128. PMC 3892339. PMID 24106028.

- ^ van Wolferen M, Ma X, Albers SV (September 2015). "DNA Processing Proteins Involved in the UV-Induced Stress Response of Sulfolobales". Journal of Bacteriology. 197 (18): 2941–51. doi:10.1128/JB.00344-15. PMC 4542170. PMID 26148716.

- ^ Melcher U (2001). "Molecular genetics: Horizontal gene transfer". Stillwater, Oklahoma USA: Oklahoma State University. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-08-20.

- ^ Blanchard JL, Lynch M (July 2000). "Organellar genes: why do they end up in the nucleus?". Trends in Genetics. 16 (7): 315–20. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02053-9. PMID 10858662. Discusses theories on how mitochondria and chloroplast genes are transferred into the nucleus, and also what steps a gene needs to go through in order to complete this process.

- ^ Davis CC, Wurdack KJ (July 2004). "Host-to-parasite gene transfer in flowering plants: phylogenetic evidence from Malpighiales". Science. 305 (5684): 676–8. Bibcode:2004Sci...305..676D. doi:10.1126/science.1100671. PMID 15256617. S2CID 16180594.

- ^ Nickrent DL, Blarer A, Qiu YL, Vidal-Russell R, Anderson FE (October 2004). "Phylogenetic inference in Rafflesiales: the influence of rate heterogeneity and horizontal gene transfer". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 4 (1): 40. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-4-40. PMC 528834. PMID 15496229.

- ^ Woloszynska M, Bocer T, Mackiewicz P, Janska H (November 2004). "A fragment of chloroplast DNA was transferred horizontally, probably from non-eudicots, to mitochondrial genome of Phaseolus". Plant Molecular Biology. 56 (5): 811–20. doi:10.1007/s11103-004-5183-y. PMID 15803417. S2CID 14198321.

- ^ Hall C, Brachat S, Dietrich FS (June 2005). "Contribution of horizontal gene transfer to the evolution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Eukaryotic Cell. 4 (6): 1102–15. doi:10.1128/EC.4.6.1102-1115.2005. PMC 1151995. PMID 15947202.

- ^ Quispe-Huamanquispe DG, Gheysen G, Kreuze JF (2017). "Agrobacterium T-DNAs". Frontiers in Plant Science. 8: 2015. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.02015. PMC 5705623. PMID 29225610.

- ^ Lee Phillips M (2012). "Bacterial gene helps coffee beetle get its fix". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.10116. S2CID 211729274.

- ^ Acuña R, Padilla BE, Flórez-Ramos CP, Rubio JD, Herrera JC, Benavides P, et al. (March 2012). "Adaptive horizontal transfer of a bacterial gene to an invasive insect pest of coffee". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (11): 4197–202. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.4197A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121190109. PMC 3306691. PMID 22371593.

- ^ Traci Watson (15 November 2012). "Bdelloids Surviving on Borrowed DNA". Science/AAAS News.

- ^ Koutsovoulos G, Kumar S, Laetsch DR, Stevens L, Daub J, Conlon C, et al. (May 2016). "No evidence for extensive horizontal gene transfer in the genome of the tardigrade Hypsibius dujardini". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (18): 5053–8. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.5053K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1600338113. PMC 4983863. PMID 27035985.

- ^ Crisp A, Boschetti C, Perry M, Tunnacliffe A, Micklem G (March 2015). "Expression of multiple horizontally acquired genes is a hallmark of both vertebrate and invertebrate genomes". Genome Biology. 16: 50. doi:10.1186/s13059-015-0607-3. PMC 4358723. PMID 25785303.

- ^ Madhusoodanan J (2015-03-12). "Horizontal Gene Transfer a Hallmark of Animal Genomes?". The Scientist. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ^ Redrejo-Rodríguez M, Muñoz-Espín D, Holguera I, Mencía M, Salas M (November 2012). "Functional eukaryotic nuclear localization signals are widespread in terminal proteins of bacteriophages". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (45): 18482–7. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10918482R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1216635109. PMC 3494942. PMID 23091024.

- ^ Kondo N, Nikoh N, Ijichi N, Shimada M, Fukatsu T (October 2002). "Genome fragment of Wolbachia endosymbiont transferred to X chromosome of host insect". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (22): 14280–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914280K. doi:10.1073/pnas.222228199. PMC 137875. PMID 12386340.

- ^ Dunning Hotopp JC, Clark ME, Oliveira DC, Foster JM, Fischer P, Muñoz Torres MC, et al. (September 2007). "Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes". Science. 317 (5845): 1753–6. Bibcode:2007Sci...317.1753H. doi:10.1126/science.1142490. PMID 17761848. S2CID 10787254.

- ^ Yoshida S, Maruyama S, Nozaki H, Shirasu K (May 2010). "Horizontal gene transfer by the parasitic plant Striga hermonthica". Science. 328 (5982): 1128. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1128Y. doi:10.1126/science.1187145. PMID 20508124. S2CID 39376164.

- ^ Carl Zimmer (April 17, 2014). "Plants That Practice Genetic Engineering". New York Times.

- ^ Schwartz JA, Curtis NE, Pierce SK (December 2014). "FISH labeling reveals a horizontally transferred algal (Vaucheria litorea) nuclear gene on a sea slug (Elysia chlorotica) chromosome". The Biological Bulletin. 227 (3): 300–12. doi:10.1086/BBLv227n3p300. PMID 25572217.

- ^ Rauch C, Vries J, Rommel S, Rose LE, Woehle C, Christa G, et al. (August 2015). "Why It Is Time to Look Beyond Algal Genes in Photosynthetic Slugs". Genome Biology and Evolution. 7 (9): 2602–7. doi:10.1093/gbe/evv173. PMC 4607529. PMID 26319575.

- ^ Bhattacharya D, Pelletreau KN, Price DC, Sarver KE, Rumpho ME (August 2013). "Genome analysis of Elysia chlorotica Egg DNA provides no evidence for horizontal gene transfer into the germ line of this Kleptoplastic Mollusc". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 30 (8): 1843–52. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst084. PMC 3708498. PMID 23645554.

- ^ a b Moran NA, Jarvik T (April 2010). "Lateral transfer of genes from fungi underlies carotenoid production in aphids". Science. 328 (5978): 624–7. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..624M. doi:10.1126/science.1187113. PMID 20431015. S2CID 14785276.

- ^ Fukatsu T (April 2010). "Evolution. A fungal past to insect color". Science. 328 (5978): 574–5. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..574F. doi:10.1126/science.1190417. PMID 20431000. S2CID 23686682.

- ^ Bar D (16 February 2011). "Evidence of Massive Horizontal Gene Transfer Between Humans and Plasmodium vivax". Nature Precedings. doi:10.1038/npre.2011.5690.1.

- ^ "Human beings' ancestors have routinely stolen genes from other species". The Economist. 14 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Salzberg SL, White O, Peterson J, Eisen JA (June 2001). "Microbial genes in the human genome: lateral transfer or gene loss?". Science. 292 (5523): 1903–6. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1903S. doi:10.1126/science.1061036. PMID 11358996. S2CID 17016011.

- ^ Ivics Z, Hackett PB, Plasterk RH, Izsvák Z (November 1997). "Molecular reconstruction of Sleeping Beauty, a Tc1-like transposon from fish, and its transposition in human cells". Cell. 91 (4): 501–10. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80436-5. PMID 9390559. S2CID 17908472.

- ^ Plasterk RH (1996). "The Tc1/mariner transposon family". In Saedler H, Gierl A (eds.). Transposable Elements. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 204. pp. 125–143. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-79795-8_6. ISBN 978-3-642-79797-2. PMID 8556864.

- ^ Izsvák Z, Ivics Z, Plasterk RH (September 2000). "Sleeping Beauty, a wide host-range transposon vector for genetic transformation in vertebrates". Journal of Molecular Biology. 302 (1): 93–102. doi:10.1006/jmbi.2000.4047. PMID 10964563.

- ^ Kurtti TJ, Mattila JT, Herron MJ, Felsheim RF, Baldridge GD, Burkhardt NY, et al. (October 2008). "Transgene expression and silencing in a tick cell line: A model system for functional tick genomics". Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 38 (10): 963–8. doi:10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.07.008. PMC 2581827. PMID 18722527.

- ^ Graham Lawton Why Darwin was wrong about the tree of life New Scientist Magazine issue 2692 21 January 2009 Accessed February 2009

- ^ Genomic analysis of Hyphomonas neptunium contradicts 16S rRNA gene-based phylogenetic analysis: implications for the taxonomy of the orders 'Rhodobacterales' and Caulobacteraes

- ^ Zhaxybayeva O, Gogarten JP (April 2004). "Cladogenesis, coalescence and the evolution of the three domains of life". Trends in Genetics. 20 (4): 182–7. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2004.02.004. PMID 15041172.

- ^ a b c Doolittle WF (February 2000). "Uprooting the tree of life". Scientific American. 282 (2): 90–5. Bibcode:2000SciAm.282b..90D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0200-90. PMID 10710791.

- ^ Woese CR (June 2004). "A new biology for a new century". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 68 (2): 173–86. doi:10.1128/MMBR.68.2.173-186.2004. PMC 419918. PMID 15187180.

- ^ Theobald DL (May 2010). "A formal test of the theory of universal common ancestry". Nature. 465 (7295): 219–22. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..219T. doi:10.1038/nature09014. PMID 20463738. S2CID 4422345.

- ^ Huang J, Gogarten JP (2009). "Ancient gene transfer as a tool in phylogenetic reconstruction". Horizontal Gene Transfer. Methods in Molecular Biology. 532. Humana Press. pp. 127–39. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-853-9_7. ISBN 9781603278522. PMID 19271182.

- ^ Davín AA, Tannier E, Williams TA, Boussau B, Daubin V, Szöllősi GJ (May 2018). "Gene transfers can date the tree of life". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (5): 904–909. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0525-3. PMC 5912509. PMID 29610471.

- ^ Wolfe JM, Fournier GP (May 2018). "Horizontal gene transfer constrains the timing of methanogen evolution". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (5): 897–903. doi:10.1038/s41559-018-0513-7. hdl:1721.1/118329. PMID 29610466. S2CID 4968981.

- ^ Oliveira PH, Touchon M, Cury J, Rocha EP (October 2017). "The chromosomal organization of horizontal gene transfer in bacteria". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 841. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..841O. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00808-w. PMC 5635113. PMID 29018197.

- ^ Bryant DA, Frigaard NU (November 2006). "Prokaryotic photosynthesis and phototrophy illuminated". Trends in Microbiology. 14 (11): 488–96. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001. PMID 16997562.

- ^ Avrain L, Vernozy-Rozand C, Kempf I (2004). "Evidence for natural horizontal transfer of tetO gene between Campylobacter jejuni strains in chickens". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 97 (1): 134–40. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02306.x. PMID 15186450.

- ^ Darkened Forests, Ferns Stole Gene From an Unlikely Source — and Then From Each Other Archived 2016-03-07 at the Wayback Machine by Jennifer Frazer (May 6, 2014). Scientific American.

- ^ Li FW, Rothfels CJ, Melkonian M, Villarreal JC, Stevenson DW, Graham SW, et al. (2015). "The origin and evolution of phototropins". Frontiers in Plant Science. 6: 637. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00637. PMC 4532919. PMID 26322073.

- ^ Wybouw N, Dermauw W, Tirry L, Stevens C, Grbić M, Feyereisen R, Van Leeuwen T (April 2014). "A gene horizontally transferred from bacteria protects arthropods from host plant cyanide poisoning". eLife. 3: e02365. doi:10.7554/eLife.02365. PMC 4011162. PMID 24843024.

- ^ Yong E (2011-02-16). "Gonorrhea has picked up human DNA (and that's just the beginning)". National Geographic. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

Further reading[edit]

- Gyles C, Boerlin P (March 2014). "Horizontally transferred genetic elements and their role in pathogenesis of bacterial disease". Veterinary Pathology. 51 (2): 328–40. doi:10.1177/0300985813511131. PMID 24318976. S2CID 206510894.

- – Papers by Dr Michael Syvanen on Horizontal Gene Transfer

- Salzberg SL, White O, Peterson J, Eisen JA (June 2001). "Microbial genes in the human genome: lateral transfer or gene loss?" (PDF). Science. 292 (5523): 1903–6. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1903S. doi:10.1126/science.1061036. PMID 11358996. S2CID 17016011.

About 40 genes were found to be exclusively shared by humans and bacteria and are candidate examples of horizontal transfer from bacteria to vertebrates. Gene loss combined with sample size effects and evolutionary rate variation provide an alternative, more biologically plausible explanation

- Qi Z, Cui Y, Fang W, Ling L, Chen R (January 2004). "Autosomal similarity revealed by eukaryotic genomic comparison". Journal of Biological Physics. 30 (4): 305–12. doi:10.1007/s10867-004-0996-0. PMC 3456315. PMID 23345874.

- Woese CR (June 2002). "On the evolution of cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (13): 8742–7. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.8742W. doi:10.1073/pnas.132266999. PMC 124369. PMID 12077305. This article seeks to shift the emphasis in early phylogenic adaptation from vertical to horizontal gene transfer. He uses the term "Darwinian Threshold" for the time of major transition of evolutionary mechanisms from mostly horizontal to mostly vertical transfer, and the "origin of speciation".

- Snel B, Bork P, Huynen MA (January 1999). "Genome phylogeny based on gene content". Nature Genetics. 21 (1): 108–10. doi:10.1038/5052. PMID 9916801. S2CID 10296406. This article proposes using the presence or absence of a set of genes to infer phylogenies, in order to avoid confounding factors such as horizontal gene transfer.

- "Webfocus in Nature with free review articles". Archived from the original on 2005-11-02.

- Patil PB, Sonti RV (October 2004). "Variation suggestive of horizontal gene transfer at a lipopolysaccharide (lps) biosynthetic locus in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae, the bacterial leaf blight pathogen of rice". BMC Microbiology. 4 (1): 40. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-4-40. PMC 524487. PMID 15473911.

- Jin G, Nakhleh L, Snir S, Tuller T (November 2006). "Maximum likelihood of phylogenetic networks". Bioinformatics. 22 (21): 2604–11. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl452. PMID 16928736.

- Jain R, Rivera MC, Lake JA (March 1999). "Horizontal gene transfer among genomes: the complexity hypothesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (7): 3801–6. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.3801J. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.3801. PMC 22375. PMID 10097118.

- Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA (May 2000). "Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation". Nature. 405 (6784): 299–304. doi:10.1038/35012500. PMID 10830951. S2CID 85739173.

- Preston R (July 12, 1999). "The Demon in the Freezer". The New Yorker. pp. 44–61.

Smallpox knows how to make a mouse protein. How did smallpox learn that? 'The poxviruses are promiscuous at capturing genes from their hosts,' Esposito said. 'It tells you that smallpox was once inside a mouse or some other small rodent.'

- Szpirer C, Top E, Couturier M, Mergeay M (December 1999). "Retrotransfer or gene capture: a feature of conjugative plasmids, with ecological and evolutionary significance". Microbiology. 145 ( Pt 12) (Pt 12): 3321–3329. doi:10.1099/00221287-145-12-3321. PMID 10627031.

- "Can transgenes from genetically modified plants be absorbed by micro-organisms and spread in this way?". GMO Safety: Results of research into horizontal gene transfer. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21.

- Whitaker JW, McConkey GA, Westhead DR (2009). "The transferome of metabolic genes explored: analysis of the horizontal transfer of enzyme encoding genes in unicellular eukaryotes". Genome Biology. 10 (4): R36. doi:10.1186/gb-2009-10-4-r36. PMC 2688927. PMID 19368726.

External links[edit]

| Scholia has a topic profile for Horizontal gene transfer. |

- Citizendium:Horizontal gene transfer

- Citizendium:Horizontal gene transfer in prokaryotes

- Citizendium:Horizontal gene transfer in plants

- Citizendium:Horizontal gene transfer (History)