| Chica con un pendiente de perla | |

|---|---|

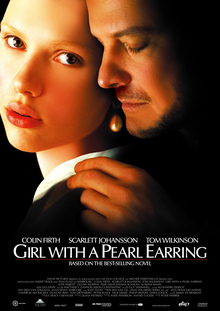

Cartel de estreno en cines del Reino Unido | |

| Dirigido por | Peter Webber |

| Producido por | |

| Guión por | Olivia Hetreed |

| Residencia en | Chica con un pendiente de perlas de Tracy Chevalier |

| Protagonizada | |

| Musica por | Alexandre Desplat |

| Cinematografía | Eduardo Serra |

| Editado por | Kate Evans |

| producción empresas |

|

| Distribuido por |

|

| Fecha de lanzamiento |

|

| Tiempo de ejecución | 100 minutos |

| Países | |

| Idioma | inglés |

| Presupuesto | £ 10 millones |

| Taquilla | $ 31,4 millones |

Girl with a Pearl Earring es una película de drama de 2003dirigida por Peter Webber . El guión fue adaptado por el guionista Olivia Hetreed desde el 1999 novela del mismo nombre por Tracy Chevalier . Scarlett Johansson interpreta a Griet, una joven sirvienta del siglo XVII en la casa del pintor holandés Johannes Vermeer (interpretado por Colin Firth ) en el momento en que pintó Chica con un pendiente de perla (1665) en la ciudad de Delft en Holanda . Otros miembros del elenco incluyen a Tom Wilkinson , Cillian Murphy yJudy Parfitt .

Hetreed leyó la novela antes de su publicación y la productora de su marido convenció a Chevalier de vender los derechos cinematográficos . Inicialmente, la producción iba a presentar a Kate Hudson como Griet con la dirección de Mike Newell . Hudson se retiró poco antes de que comenzara la filmación, sin embargo, y la película se puso en pausa hasta la contratación de Webber, quien reinició el proceso de casting.

En su debut cinematográfico, Webber trató de evitar emplear características tradicionales del drama cinematográfico de época . [4] En una entrevista de 2003 con IGN, dijo: "Lo que me asustaba era terminar con algo que fuera como Masterpiece Theatre , [ese] tipo de cosa muy educada de la BBC del domingo por la noche, y estaba decidido a hacer algo bastante diferente a eso ... ". El director de fotografía Eduardo Serra utilizó una iluminación distintiva y esquemas de color similares a las pinturas de Vermeer.

Lanzada el 12 de diciembre de 2003 en Norteamérica y el 16 de enero de 2004 en el Reino Unido, Girl with a Pearl Earring obtuvo una recaudación mundial bruta de 31,4 millones de dólares. Obtuvo una recepción crítica mayoritariamente positiva, y los críticos generalmente aplaudieron las imágenes y las actuaciones de la película mientras cuestionaban elementos de su historia. Posteriormente, la película fue nominada a diez premios de cine de la Academia Británica , tres premios de la Academia y dos premios Globo de Oro .

Trama [ editar ]

Griet es una niña tímida que vive en la República Holandesa en 1665. Su padre, un pintor de Delftware , se ha quedado ciego recientemente, lo que le impide trabajar y deja a su familia en una situación económica precaria. Griet es enviada a trabajar como sirvienta en la casa del famoso pintor Johannes Vermeer y su esposa, Catharina. En el camino, se detiene momentáneamente en un cruce de caminos.

Griet trabaja con diligencia y casi sin palabras en la posición más baja de una dura jerarquía. Ella hace todo lo posible por adaptarse, a pesar del trato cruel de la hija adolescente malcriada de Vermeer, Cornelia. Mientras Griet está de compras, el hijo de un carnicero, Pieter, se siente atraído por ella. Ella tarda en devolver sus afectos a medida que se desarrolla su relación. Mientras Griet limpia el estudio de Vermeer, en el que Catharina nunca entra, la pintora comienza a conversar con ella y la anima a apreciar la pintura, la luz y el color. Él le da lecciones sobre cómo mezclar pinturas y otras tareas mientras mantiene estos secretos de Catharina, para evitar enojarla. Por el contrario, la pragmática suegra de Vermeer, Maria Thins , ve a Griet como útil para la carrera de Vermeer.

El rico mecenas de Vermeer , Van Ruijven , visita la casa y se da cuenta de Griet. Él pregunta si Vermeer renunciará a Griet para que pueda trabajar en la casa del patrón, donde Van Ruijven " arruinóVermeer se niega, pero acepta pintar un retrato de Griet para Van Ruijven. Mientras él trabaja en secreto en la pintura, Catharina se da cuenta de que algo anda mal. Su creciente desdén por la criada se hace evidente, estimulado por Van Ruijven sugerencias deliberadas de una relación inapropiada entre Vermeer y Griet. Griet en conflicto se ocupa de su creciente fascinación por Vermeer y su talento mientras se defiende de Van Ruijven, que intenta violarla en el patio. Más tarde, cuando Catharina está fuera por el día, su La madre le entrega a Griet los pendientes de perlas de su hija y le pide a Vermeer que termine la pintura.

En la última sesión de pintura, Vermeer perfora el lóbulo de la oreja izquierda de Griet para que pueda usar uno de los pendientes para el retrato. La tensión aumenta cuando ella reacciona con dolor y Vermeer le acaricia la cara. Corre hacia Pieter en busca de consuelo y distracción de sus pensamientos sobre Vermeer. Los dos hacen el amor en un granero. Pieter propone matrimonio, pero Griet se marcha inesperadamente. Devuelve los pendientes a la madre de Catharina.

Catharina se enfurece al descubrir que Griet llevaba sus pendientes y entra en el estudio, acusando a su madre de complicidad. Ella exige que Vermeer le muestre el retrato encargado. Ofendida por la naturaleza íntima de la pintura, Catharina la descarta como "obscena" y entre lágrimas pregunta por qué Vermeer no la pintaría. Cuando Vermeer responde que no comprende, intenta destruir la pintura, pero no logra. Ella destierra a Griet de la casa. Vermeer no se opone. Griet regresa a la casa de sus padres y se encuentra una vez más en una encrucijada. Más tarde, recibe la visita en la casa de sus padres de la cocinera de Vermeer, Tanneke, quien trae un regalo: el pañuelo azul que Griet usó en la pintura, envuelto alrededor de los pendientes de perlas de Catharina.

En la escena final, Van Ruijven se sienta mirando con aire de suficiencia la pintura de la vida real, Chica con un pendiente de perla .

Transmitir [ editar ]

- Colin Firth como Johannes Vermeer

- Scarlett Johansson como Griet

- Tom Wilkinson como Pieter van Ruijven

- Judy Parfitt como Maria Thins

- Cillian Murphy como Pieter

- Essie Davis como Catharina Vermeer

- Joanna Scanlan como Tanneke

- Alakina Mann como Cornelia Vermeer

- Chris McHallem como el padre de Griet

- Gabrielle Reidy como la madre de Griet

- Rollo Weeks como Frans

- Anna Popplewell como Maertge

- Geoff Bell como Paul el carnicero

- John McEnery como boticario

Producción [ editar ]

Desarrollo [ editar ]

Este artículo contiene demasiadas citas o demasiado largas para una entrada enciclopédica . ( Febrero de 2020 ) |

La producción de Girl with a Pearl Earring comenzó en 1999, cuando la guionista Olivia Hetreed obtuvo acceso a la novela de Tracy Chevalier Girl with a Pearl Earring poco antes de su publicación en agosto. [5] [nota 1] La novela aún no se había convertido en un éxito de ventas, pero varios grupos estaban comenzando a mostrar interés. [6] A Hetreed le encantaba el personaje de Griet y "su determinación de ser libre en un mundo en el que eso era casi imposible para una chica de su entorno". [9] Anand Tucker y el marido de Hetreed, Andy Paterson , ambos productores del pequeño estudio británico Archer Street Films [8] [10] - se acercó a la autora de la novela, Tracy Chevalier , para una adaptación cinematográfica. Chevalier estuvo de acuerdo, creyendo que un estudio británico ayudaría a resistir el impulso de Hollywood de "darle vida a la película". [6] [11] Ella estipuló que su adaptación evita que los personajes principales consuman su relación. Paterson y Tucker prometieron "replicar la 'verdad emocional' de la historia [...]", y Chevalier no buscó retener el control durante el proceso creativo de la película, aunque consideró brevemente adaptarla ella misma. [6] [12]

Hetreed trabajó en estrecha colaboración con Tucker y Webber para adaptar el libro, explicando que "trabajar con ellos en los borradores me ayudó a concentrarme en lo que sería la película, en lugar de lo bien que podría hacer funcionar una línea". [6] Su primer borrador estaba más cerca del material original y lentamente "desarrolló su propio carácter" a través de reescrituras. [6] Evitó usar una voz en off, que estaba presente en la novela, "en parte porque la haría muy literaria". [6] En cambio, se centró en transmitir los pensamientos de Griet visualmente, por ejemplo, en su adaptación Griet y Vermeer inspeccionan la cámara oscura.juntos bajo su manto en medio de la tensión sexual; mientras que, en la novela, Griet lo ve solo inmediatamente después de él y disfruta del calor y el aroma duraderos que deja. [6] [13]

La novela maximiza los pocos hechos conocidos de la vida de Vermeer, que Hetreed describió como "pequeños pilares que sobresalen del polvo de la historia". [6] Para aprender más sobre el artista, el guionista investigó la sociedad holandesa en el siglo XVII, habló con amigos artistas sobre pintura y entrevistó a un historiador de arte del Victoria & Albert Museum que había restaurado la obra de arte original . [6] Hetreed se mantuvo en estrecho contacto con Chevalier, y los dos se volvieron tan cercanos cerca del final de la producción que presentaron juntos una clase magistral sobre escritura de guiones. [9]

Casting [ editar ]

Originalmente, la actriz estadounidense Kate Hudson fue elegida para interpretar a Griet, [10] después de haber obtenido con éxito el papel de los productores de la película. En septiembre de 2001, sin embargo, Hudson se retiró cuatro semanas antes de que comenzara la filmación, oficialmente debido a "diferencias creativas". [14] [15] La decisión de Hudson arruinó la producción y provocó la pérdida del apoyo financiero de la productora Intermedia . También resultó en la retirada de Mike Newell como director y Ralph Fiennes como Vermeer; Fiennes dejó el proyecto para trabajar en su película Maid in Manhattan de 2002 . [5] Debido a este incidente, The Guardianinformó que "ahora parece poco probable que la película se haga alguna vez". [14]

La producción comenzó de nuevo ese mismo año cuando los productores contrataron al relativamente desconocido director de televisión británico Peter Webber para dirigir el proyecto, [9] [16] a pesar de que no había dirigido un largometraje antes. [8] [17] Tucker y Paterson ya conocían a Webber de varios proyectos anteriores; [9] el director descubrió el proyecto por accidente después de visitar su oficina, donde notó un cartel del trabajo de Vermeer y comenzó a discutirlo. [16] Webber leyó el guión y lo describió como "sobre la creatividad y el vínculo entre el arte y el dinero y el poder y el sexo en una extraña mezcla impía". [18] Caracterizándolo como una " mayoría de edad"historia con una" fascinante resaca oscura ", [8] Webber deliberadamente no leyó el libro antes de la filmación, ya que estaba preocupado por ser influenciado por él, optando en cambio por confiar en el guión y el período. [19]

El casting de Griet fue el primer gran paso de Webber y llevó a entrevistas con 150 chicas antes de que Webber eligiera a la actriz de 17 años Scarlett Johansson . Sintió que ella "simplemente se destacó. Tenía algo distintivo en ella". [17] Johansson le parecía muy moderno a Webber, pero creía que esto era un atributo positivo, al darse cuenta de que "lo que funcionaría era tomar a esta chica inteligente y enérgica y reprimir todo eso". [8] La actriz terminó de filmar Lost in Translation inmediatamente antes de llegar al set en Luxemburgo y, en consecuencia, se preparó poco para el papel. Consideró que el guión estaba "bellamente escrito" y el personaje "muy conmovedor", [20]pero no leyó el libro porque pensó que sería mejor abordar la historia con "borrón y cuenta nueva". [8] [21]

Después de la contratación de Johansson, se tomaron rápidamente otras decisiones importantes sobre el reparto, comenzando con la incorporación del actor inglés Colin Firth como Vermeer. [16] Firth y Webber, ambos de edad y antecedentes similares, pasaron un tiempo considerable discutiendo la personalidad y el estilo de vida de Vermeer en el período previo al comienzo de la filmación. [20] Mientras investigaba el papel, Firth se dio cuenta de que Vermeer era "increíblemente esquivo como artista". [8] Como resultado, a diferencia de Webber y Johansson, Firth decidió leer el libro para comprender mejor a un hombre del que existía poca información sobre su vida privada. [19]Firth buscó "inventar" el personaje y descubrir sus motivaciones, y finalmente se identificó con el artista por tener un espacio privado en medio de una bulliciosa familia. Firth también estudió técnicas de pintura y visitó museos con obras de Vermeer. [8] [22]

Después de Firth, la siguiente decisión de casting de Webber fue Tom Wilkinson como el mecenas Pieter van Ruijven, quien fue contratado a finales de 2002. [16] [23] Pronto se le unieron Judy Parfitt como la dominante suegra de Vermeer, y Essie Davis, quien interpretó a la esposa de Vermeer, Catharina. [9] [16] La hija australiana de un artista, Davis no creía que su personaje fuera el "chico malo" de la película, ya que "[Catharina] tiene cierto papel que desempeñar para que quieras que Griet y Vermeer se involucren". [24] Cillian Murphy, conocido por su papel reciente en 28 Days Later , fue contratado como Pieter, el interés amoroso del carnicero de Griet. [25]Murphy, que asumió su primer papel en una película de época, estaba interesado en servir como contraste con Vermeer de Firth y representar el mundo "ordinario" que Griet busca evitar al conocer al artista. [9] Otros miembros del reparto incluyeron a Joanna Scanlan como la sirvienta Tanneke, así como a las jóvenes actrices Alakina Mann y Anna Popplewell como las hijas de Vermeer, Cornelia y Maertge, respectivamente. [9]

Filmando [ editar ]

Este artículo contiene demasiadas citas o demasiado largas para una entrada enciclopédica . ( Febrero de 2020 ) |

Durante la preproducción, Webber y el director de fotografía Eduardo Serra estudiaron la obra de arte de la época y discutieron los diferentes estados de ánimo que querían crear para cada escena. [26] El director era un amante del drama de época de Stanley Kubrick , Barry Lyndon , pero sabía que Girl With a Pearl Earring sería diferente; a diferencia de las "piezas elaboradas y costosas" de la película anterior, la producción de Webber debía ser "sobre las relaciones íntimas dentro de una sola casa". [27] No buscaba crear una película biográfica históricamente precisa de Vermeer; [19] Webber buscó dirigir una película de época que evitara ser "excesivamente servil".a las características delgénero , deseando en cambio "dar vida a la película" y que los espectadores "puedan casi oler la carne en el mercado". [8] Webber empleó poco diálogo y se inspiró en el "mundo tranquilo, tenso, misterioso y trascendente" de las pinturas de Vermeer. [18] El director también hizo un esfuerzo consciente por ralentizar el ritmo de la película, con la esperanza de que al "ralentizar las cosas [pudiéramos] crear estos momentos entre el diálogo que estaban llenos de emoción. Y cuanto más silenciosa se volvía la película, cuanto más cerca parecía estar de la condición de esas pinturas de Vermeer y más cerca parecía captar algún tipo de verdad ". [28]

La película fue presupuestada en £ 10 millones. [10] Aunque está ambientada en Delft, la película se rodó principalmente en Ámsterdam, Bélgica y Luxemburgo. [12] [29] Chevalier comentó más tarde que Webber y Serra "necesitaban un control absoluto del espacio y la luz con los que trabajaban, algo que nunca podrían lograr cerrando una calle concurrida de Delft durante una o dos horas". [12] Solo se filmaron algunas tomas exteriores en Delft. [8]

Webber contrató a Ben van Os como diseñador de producción porque "no estaba intimidado por las obligaciones de la época. Estaba mucho más interesado en la historia y el personaje". [27] Para inspirarse en la construcción de los decorados de la película, Webber y van Os estudiaron las obras de Vermeer y otros artistas de la época, como Gerard ter Borch . [8] El diseñador de escenarios Todd van Hulzen dijo que el objetivo era "reflejar esa ética tranquila, sobria y casi moralizante que se ve en las pinturas holandesas". [8]Construyeron la casa de Vermeer en uno de los escenarios de sonido de películas más grandes de Luxemburgo, un set de tres pisos donde diseñaron habitaciones que debían transmitir una falta de privacidad. Según van Os, la película trataba de "ser observada", por lo que tenían la intención de que Griet siempre sintiera que la estaban observando. [27] Además, construyeron otros dos decorados interiores para representar las casas de Griet y van Ruijven: la casa de Griet poseía características calvinistas, mientras que la de Van Ruijven contenía animales montados para reflejar su "naturaleza depredadora". [27] El museo Mauritshuis hizo una fotografía de alta resolución de la pintura real, que luego fue filmada en una cámara de tribuna para ser utilizada en la película. [30]

Según Webber, Serra "estaba obsesionado con reproducir el asombroso uso de la luz por parte de los artistas de ese período, y más particularmente el uso de Vermeer". [26] Para reflejar la "luminosidad mágica" de la obra de arte de Vermeer, Serra empleó iluminación difusa y diferentes películas al filmar escenas en el estudio del artista. [8] Sin embargo, Webber y Serra no querían depender demasiado de la estética de Vermeer; querían que el público saliera centrando sus elogios en su historia, no en sus imágenes. [26]

Diseño de vestuario y maquillaje [ editar ]

In desiring to avoid stereotypes of the costume drama, Webber costumed his actors in simple outfits he termed "period Prada," rather than use the ruffles and baggy costumes common for the era. The intent was to "take the real clothes from the period and reduce them to their essence."[27] Costume designer Dien van Straalen explored London and Holland markets in search for period fabrics, including curtains and slipcovers.[27] For Griet, van Straalen employed "pale colors for Scarlett Johansson to give her the drab look of a poor servant girl."[27] Firth was also outfitted simply, as Vermeer was not rich.[27] Van Straalen created more elaborate costumes for Wilkinson, as van Ruijven was to her "a peacock strutting around with his money."[27]

Make-up and hair designer Jenny Shircore desired that Griet appear without make-up, so Johansson was given very little; rather, Shircore focused on maintaining the actress' skin as "milky, thick and creamy ," and bleached her eyebrows.[27] They gave Davis as Catharina a "very simple Dutch hairstyle", which they learned from studying drawings and prints of the period.[27]

Music[edit]

The musical score for Girl with a Pearl Earring was written by the French composer Alexandre Desplat. Webber decided to hire Desplat after hearing a score he had composed for a Jacques Audiard film. Webber explained, "He had a sense of restraint and a sense of lyricism that I liked. I remember the first time I saw the cue where Griet opens the shutters. He was really describing what the light was doing, articulating that in a musical sphere."[31] Desplat was then known primarily for scoring films in his native language.[32][33]

The score employs strings, piano, and woodwinds, with a central theme featuring a variety of instrumental forms.[34] Desplat created a melody that recurs throughout the film, stating in a later interview that "it evolves and it's much more flowing with a very gentle theme that's haunting."[35] The score, his career breakthrough, gained him international attention and garnered him further film projects.[36][37] The soundtrack was released in 2004;[34] it earned a nomination for the Golden Globe Award for Best Original Score, helping increase Desplat's name recognition in Hollywood.[38]

Desplat's work also garnered positive reviews. The New York Times described it as a " gorgeous score ...[which] brushes in a haunted gloom that gives the picture life where none seems to exist,"[39] whilst Boston.com said it "burbles with elegant baroque minimalism."[40] Empire magazine called his score "a supremely elegant work" that "creates a captivating atmosphere of cautious emotion and wonderment, the true highlight being 'Colours in the Clouds', so simply majestic that it really captures the heart of the story."[34]

Editing[edit]

In the interest of shortening the adaptation, approximately one-third of the story was eventually edited out;[6] entire subplots and characters were removed.[12] Before becoming a screenwriter Hetreed worked as an editor, and credits this experience for knowing "about structure and what you need to say and what you can leave out. I am a big enthusiast for leaving things out."[41] She focused the story on the relationship between Griet and Vermeer, deciding what other storylines were "distracting and had to be jettisoned. Before editing, there was great stuff there, but Peter was fantastically ruthless."[6] Changes from the novel did not bother Chevalier, who felt that as a result the film gained "a focused, driven plot and a sumptuous visual feast."[12]

Themes and analysis[edit]

According to Webber, Girl with a Pearl Earring is "more than just a quaint little film about art" but is concerned with themes of money, sex, repression, obsession, power, and the human heart.[20] Laura M. Sager Eidt in her book, Writing and Filming the Painting: Ekphrasis in Literature and Film, asserts that the film deviates significantly from the source material and emphasises a "socio-political dimension that is subtler in the novel."[42] Girl with a Pearl Earring, Sager Eidt says, "shifts its focus from a young girl's evolving consciousness to the class and power relations in the story."[43]

In his work, Film England: Culturally English Filmmaking Since the 1990s, author Andrew Higson notes that the film overcomes the novel's "subjective narration" device by having the camera stay fixed on Griet for much of the film. But, Higson says, "no effort is made to actually render her point of view as the point of view of the film or the spectator."[44]

Vermeer channels Griet's sexual awakening into his painting, with the piercing of her ear and his directives to her posing being inherently sexual.[45][46] In the opinion of psychologist Rosemary Rizq, the pearl Griet dons is a metaphor, something which normally would convey wealth and status. But, when worn by Griet the pearl is also a directive to the audience to look at the "psychological potential within" her erotic, unconsummated bond with Vermeer, unclear up to that point if it is real or not.[47]

The film incorporates seven of Vermeer's paintings into its story.[48][note 2] Thomas Leitch, in his book Film Adaptation and Its Discontents: From Gone with the Wind to The Passion of the Christ, writes that while Chevalier's Griet describes ten Vermeer paintings (without naming them), Webber's film avoids "show[ing] an external world that looks like a series of Vermeer paintings," as this would have been a trivialisation of the artist's achievements.[49] Leitch adds the director "compromises by showing far fewer actual Vermeer paintings than Chevalier's Griet describes but lingering longer over the visual particulars of the studio in which he creates them."[49]

Release[edit]

Box office[edit]

Girl With a Pearl Earring's world premiere occurred at the Telluride Film Festival on 31 August 2003.[50] In North America it was distributed by Lions Gate Entertainment.[9] The film was limited in release to seven cinemas on 12 December 2003, landing in 32nd place for the week with $89,472. Lions Gate slowly increased its release to a peak of 402 cinemas by 6 February 2004.[51] Its total domestic gross was $11,670,971.[52]

The film was released in the United Kingdom on 16 January 2004[53] by Pathé Films.[9] In its opening week, the film finished in tenth place with a total of £384,498 from 106 cinemas.[54] In the UK and Ireland, the film finished in 14th place for the year with a total box office gross of £3.84 million.[55] It had a worldwide gross of $31,466,789.[52]

Home media[edit]

In the US, the Girl With a Pearl Earring DVD was released on 4 May 2004 by Lions Gate.[56] The Region 2 DVD's release on 31 May 2004 included audio commentaries from Webber, Paterson, Hetreed, and Chevalier; a featurette on "The Art of Filmmaking"; and eight deleted scenes.[57]

Reception[edit]

– Sandra Hall in a review for The Sydney Morning Herald[58]

The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes calculated a 72% approval rating based on 178 reviews, with an average score of 6.88/10. The website reported the critical consensus as "visually arresting, but the story could be told with a bit more energy."[59] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 72 out of 100, based on 37 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[60] Critical reception of Girl With a Pearl Earring was mostly positive,[49] with reviewers positively emphasizing the film's visuals and performances while questioning elements of its story. Historian Alex von Tunzelmann, writing for The Guardian, praised the film for its "sumptuous design and incredible Vermeerish appearance" but felt that "it's a bit too much like watching paint dry."[61] In The Observer, Philip French referred to the film as "quiet, intelligent and well-acted" and believed that "most people will be impressed by, and carry away in their mind's eye, the film's appearance ... [Serra, van Os, and van Strallen] have given the movie a self-conscious beauty."[62]

The BBC's review, written by Susan Hodgetts, described the film as "a superior British costume drama that expertly mixes art history with romantic fiction", which would appeal to "anyone who likes serious, intelligent drama and gentle erotic tension."[63] Hodgetts said that both Firth and Johansson gave "excellent" performances who did "a grand job of expressing feelings and emotions without the use of much dialogue, and the picture is the better for it."[63] Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times called the film an "earnest, obvious melodrama with no soul, filled with the longing silences that come after a sigh."[39] Mitchell did however laud its cinematography, production design, and musical score,[39] as did the Film Journal International's Erica Abeel. Despite praising its visuals, Abeel criticized Girl with a Pearl Earring for being "a chick flick dressed up in Old Master clothes" and for failing "to render Griet's growing artistic sensibility dramatically credible."[64] She cited its melodramatic villains as another failing, but concluded that it was "to Johansson's credit that she alone pulls something plausible out of her character."[64]

Sandra Hall of The Sydney Morning Herald praised Webber's ability to "build individual moments [such as] the crackle of a bed-sheet which has grown an ice overcoat after being hung out to dry in the wintry air", but opined that he failed to "invest these elegant reproductions of the art of the period with the emotional charge you've been set up to expect."[58] Griet and Vermeer's relationship, Hall wrote, lacked "the sense of two people breathing easily in one another's company."[58] Owen Gleiberman, writing for Entertainment Weekly, remarked that Girl with a Pearl Earring "brings off something that few dramas about artists do. It gets you to see the world through new – which is to say, old – eyes."[65] Gleiberman added that while Johansson is silent for most of the film, "the interplay on her face of fear, ignorance, curiosity, and sex is intensely dramatic."[65] In Sight & Sound, David Jays wrote that "Johansson's marvellous performance builds on the complex innocence of her screen presence (Ghost World, Lost in Translation)."[46] Jays concluded his review by praising Webber and Serra's ability to "deftly deploy daylight, candle and shadow, denying our desire to see clearly just as Vermeer refuses to explicate the situations in his paintings. The film's scenarios may be unsurprising, but Webber's solemn evocation of art in a grey world gives his story an apt, unspoken gravity."[46]

Accolades[edit]

| Award | Category | Recipients | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[66] | Best Art Direction | Ben van Os | Nominated |

| Best Cinematography | Eduardo Serra | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Dien van Straalen | Nominated | |

| Art Directors Guild[67] | Excellence in Production Design for a Period Film | Ben van Os, Christina Schaffer | Nominated |

| British Academy Film Awards[68] | Best British Film | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Olivia Hetreed | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Scarlett Johansson | Nominated | |

| Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Judy Parfitt | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction | Ben van Os | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | Eduardo Serra | Nominated | |

| Best Costume Design | Dien van Straalen | Nominated | |

| Best Makeup & Hair | Jenny Shircore | Nominated | |

| Best Score | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | |

| Outstanding Debut | Peter Webber | Nominated | |

| British Independent Film Awards[69] | Best Achievement in Production | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Scarlett Johansson | Nominated | |

| Douglas Hickox Award (Debut Director) | Peter Webber | Nominated | |

| British Society of Cinematographers | Best Cinematography Award | Eduardo Serra | Nominated |

| Camerimage[70] | Bronze Frog | Won | |

| Golden Frog | Nominated | ||

| European Film Awards[71][72] | Best Cinematographer | Eduardo Serra | Won |

| Best Composer | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards[73] | Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama | Scarlett Johansson | Nominated |

| Best Original Score | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards[74] | Best Cinematography | Eduardo Serra | Won |

| San Diego Film Critics Societys[75] | Best Cinematography | Won | |

| San Sebastián International Film Festival[76] | Best Cinematography | Won |

See also[edit]

- 2003 in film

- Girl with a Pearl Earring (play)

Notes[edit]

- ^ Screenwriter Olivia Hetreed gained early access to the book because she shared the same agent as Chevalier,[6][7] and read it in two hours.[8]

- ^ These paintings were Woman with a Water Jug, View of Delft, The Milkmaid, The Girl with the Wine Glass, Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Concert, and Woman with a Pearl Necklace.[48]

References[edit]

- ^ "British Council Film: Girl With A Pearl Earring". UK Film Council. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Girl with a Pearl Earring (2004)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ "Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003)". American Film Institute. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ https://www.ign.com/articles/2003/12/12/an-interview-with-the-director-and-stars-of-girl-with-a-pearl-earring?page=1

- ^ a b Jardine, Cassandra (9 September 2003). "I thought: 'Who's playing a prank?'". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Grandon, Marisol (15 January 2004). "'We didn't want the "Griet discovers her sexuality in front of the mirror" scene'". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Grove, Christopher (18 December 2003). "Novel adventure: deep connections to source material were key to this year's adaptations". Daily Variety. Penske Business Media. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Winters, Laura (4 January 2004). "The story beneath that calm Vermeer". The Washington Post. Nash Holdings LLC. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Girl with a Pearl Earring production notes" (Press release). Pathé Films. 2003.

- ^ a b c Membery, York; Jenny Jarvie (5 August 2001). "Kate Hudson to star as Vermeer's inspiration". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "Painting a portrait of Vermeer". The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. 5 January 2004. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e Chevalier, Tracy (28 December 2003). "Mother of Pearl". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Weddle, David (4 January 2004). "Girl With a Pearl Earring". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Hudson withdrawal scuppers British production". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. 18 September 2001. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Susman, Gary (19 September 2001). "Shining stars". Entertainment Weekly. Time Warner. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Riding, Alan (9 December 2003). "Smoldering daughter of Delft". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ a b Davies, Hugh (20 January 2004). "Small pearl takes on the Bafta blockbusters". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Brushing up on an age-old inspiration". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. 10 December 2003. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Otto, Jeff (11 December 2003). "An interview with the director and stars of Girl with a Pearl Earring". IGN. News Corporation. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Hohenadel, Kristin (14 December 2003). "Imagining an elusive Dutch painter's world". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ Gent, Paul (23 September 2008). "Tracy Chevalier on letting go of Girl with a Pearl Earring". The Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Wollman Rusoff, Jane (9 January 2004). "Being the onscreen Vermeer". The Record. North Jersey Media Group. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ Kilian, Michael (10 March 2003). "An Oscar nomination is actor's ticket to DeKalb". Chicago Tribune. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ Maynard, Kevin (2 January 2004). "Overseas sensations". USA Today. Gannett Company. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam (25 October 2002). "Murphy right 'Girl': historical pic fleshes out supporting cast". Daily Variety. Penske Business Media. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Weddle, David (12 January 2004). "Eduardo Serra Girl With a Pearl Earring". Daily Variety. Penske Business Media. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Weddle, David (13 January 2004). "Girl With a Pearl Earring". Daily Variety. Penske Business Media. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ Hansen, Liane (21 December 2003). "Profile: Film adaptation of the novel "Girl with a Pearl Earring"". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ "Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003 Movie)". PeriodDramas.com. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Cavagna, Carlo. "Girl with a Pearl Earring: A profile of the film including an interview with director Peter Webber". Aboutfilm.com. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Burlingame, Jon (7 January 2007). "Thinking in colors and textures, then writing in music". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Artist Biography by William Ruhlmann". AllMusic. All Media Network. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Romano, Andrew (11 February 2014). "Meet Alexandre Desplat, Hollywood's master composer". The Daily Beast. The Newsweek Daily Beast Company. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Graydon, Danny. "Empire's Girl with a Pearl Earring soundtrack review". Empire. Bauer Consumer Media. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Gallo, Phil (3 January 2014). "Conversations with composers: Alexandre Desplat". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Randy (5 January 2012). "Alexandre Desplat adroitly finds the proper musical key". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (23 November 2011). "Composer Alexandre Desplat is music to Oscar's ears again this season". Deadline Hollywood. PMC. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Goldwasser, Dan (January 2006). "Alexandre Desplat – Interview". Soundtrack.net. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Elvis (12 December 2003). "Girl With a Pearl Earring (2003)". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Burr, Ty (9 January 2004). "'Girl' finds the passion behind the pose". Boston.com. Boston Globe Electronic Publishing Inc. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Koseluk, Chris (18 January 2004). "Taking a page from a bestseller". The Record. North Jersey Media Group. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 22 February 2014. (subscription required)

- ^ Sager Eidt 2008, p. 184.

- ^ Sager Eidt 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Higson 2011, p. 110.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (15 January 2004). "Girl With a Pearl Earring". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Jays, David (20 December 2011). "Girl with a Pearl Earring". Sight & Sound. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Rizq 2005, p. 259.

- ^ a b Costanzo Cahir 2006, p. 252.

- ^ a b c Leitch 2009.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (1 September 2003). "Rare air at Telluride fest". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003) Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003) – International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "UK Box Office: 2004" (Press release). UK Film Council. 2005. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ "UK Film Council Statistical Yearbook Annual Review 2004/05" (PDF) (Press release). UK Film Council. 2005. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Armstrong, Jennifer (7 May 2004). "Movie on DVD Review: Girl With a Pearl Earring (2004)". Entertainment Weekly. Time Warner. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Papamichael, Stella (July 2007). "Girl with a Pearl Earring DVD (2004)". BBC. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Hall, Sandra (13 March 2004). "Girl With a Pearl Earring". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ "Girl With a Pearl Earring (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ https://www.metacritic.com/movie/girl-with-a-pearl-earring

- ^ von Tunzelmann, Alex (25 July 2013). "Girl with a Pearl Earring: plenty of style, but not a whole lot of substance". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ French, Philip (17 January 2004). "Old Masters, young servants". The Observer. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ a b Hodgetts, Susan (13 January 2004). "Girl with a Pearl Earring (2004)". BBC. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ a b Abeel, Erica (2008). "Girl With a Pearl Earring". Film Journal International. Prometheus Global Media. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b Gleiberman, Owen (3 December 2003). "Girl With a Pearl Earring Review". Entertainment Weekly. Time Warner. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ "The 76th Academy Awards (2004) Nominees and Winners" (Press release). Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "8th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards – 2003 Nominees & Winners" (Press release). Art Directors Guild. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Baftas: the full list". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. 19 January 2004. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "2004 Nominations Announced 7th British Independent Film Awards" (Press release). British Independent Film Awards. 26 October 2004. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Camerimage 2003" (Press release). International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography Plus Camerimage. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "2004: The Nominations" (Press release). European Film Academy. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Variety staff (11 December 2004). "'Head' of EFA class". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "The 61st Annual Golden Globe Awards (2004)". hfpa.org. Retrieved 13 March 2004.

- ^ "Los Angeles Film Critics Association 29th Annual Awards" (PDF) (Press release). Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Bennett, Dan (30 December 2003). "S.D. film critics name 'Dirty Pretty Things' the year's best". San Diego Union-Tribune. MLIM Holdings. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ "51 edition. 2003 Awards" (Press release). San Sebastián International Film Festival. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

Bibliography[edit]

- Costanzo Cahir, Linda (2006). Literature into Film: Theory and Practical Approaches. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2597-6.

- Higson, Andrew (2011). Film England: Culturally English Filmmaking Since the 1990s. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-454-3.

- Leitch, Thomas (2009). Film Adaptation and Its Discontents: From Gone with the Wind to The Passion of the Christ. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9271-4.

- Rizq, Rosemary (August 2005). "Finding the self in mind: Vermeer and reflective function". Psychodynamic Practice. 11 (3): 255–268. doi:10.1080/14753630500232156. S2CID 144813929.

- Sager Eidt, Laura M. (2008). Writing and Filming the Painting: Ekphrasis in Literature and Film. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2457-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Neumeyer, David (2013). "Film II". In Shephard, Tim; Leonard, Anne (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Music and Visual Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-62925-6.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Girl with a Pearl Earring at IMDb

- Girl with a Pearl Earring at AllMovie

- Girl with a Pearl Earring at Rotten Tomatoes