Este artículo necesita citas adicionales para su verificación . ( enero de 2013 ) ( Aprenda cómo y cuándo eliminar este mensaje de plantilla ) |

| señorLaurens van der PostCBE | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nació | Lourens Jan van der Post 13 de diciembre de 1906 |

| Fallecido | 16 de diciembre de 1996 (90 años) Londres , inglaterra |

| Lugar de descanso | Philippolis , Free State , Sudáfrica |

| Educación | Universidad gris , Bloemfontein |

| Esposos) | Marjorie Edith Wendt (1928-1949) Ingaret Giffard (1949-muerte) |

| Niños | 4 |

| Padres) | Christiaan van der Post Lammie van der Post |

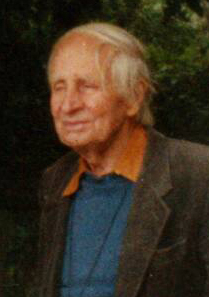

Sir Laurens Jan van der Post , CBE (13 de diciembre de 1906 - 16 de diciembre de 1996) fue un autor afrikaner sudafricano del siglo XX , agricultor, soldado, asesor político de los jefes de gobierno británicos, amigo cercano del príncipe Carlos , padrino del príncipe William , educador , periodista , humanitario , filósofo , explorador y conservacionista .

Primeros años y educación [ editar ]

Van der Post nació en la pequeña ciudad de Philippolis en la colonia del río Orange , el nombre británico posterior a la guerra de los bóers para lo que anteriormente había sido el Afrikaner Orange Free State en lo que hoy es Sudáfrica. [1] Su padre, Christiaan Willem Hendrik van der Post (1856-1914), un holandés de Leiden , había emigrado a Sudáfrica con sus padres y se había casado con Johanna Lubbe en 1889. Los van der Posts tuvieron un total de 13 hijos, con Laurens es el decimotercero. El quinto hijo. Christiaan fue abogado y político, y luchó en la Segunda Guerra de los Bóers contra los británicos. Después de la Segunda Guerra de los Bóers, fue exiliado con su familia a Stellenbosch., donde fue concebido Laurens. Regresaron a Philippolis en Orange River Colony, donde nació en 1906.

Pasó sus primeros años de infancia en la granja familiar y adquirió el gusto por la lectura en la extensa biblioteca de su padre, que incluía a Homer y Shakespeare . Su padre murió en agosto de 1914. En 1918, van der Post fue a la escuela en Gray College en Bloemfontein . Allí, escribió, fue un gran impacto para él que "lo educaran en algo que destruyó el sentido de humanidad común que compartía con la gente negra". En 1925 tomó su primer trabajo como reportero en entrenamiento en The Natal Advertiser en Durban , donde sus reportajes incluían sus propios logros jugando en el hockey sobre césped de Durban y Natal.equipos. En 1926, él y otros dos escritores rebeldes, Roy Campbell y William Plomer , publicaron una revista satírica llamada Voorslag (inglés: whip lash ) que criticaba los sistemas imperialistas; duró tres números antes de verse obligado a cerrar debido a sus controvertidas opiniones. [2] Más tarde ese año despegó durante tres meses con Plomer y navegó a Tokio y de regreso en un carguero japonés, el Canada Maru , una experiencia que produjo libros de ambos autores más tarde en la vida.

En 1927, van der Post conoció a Marjorie Edith Wendt (m. 1995), hija del fundador y director de la Orquesta de Ciudad del Cabo . La pareja viajó a Inglaterra y el 8 de marzo de 1928 se casó en Bridport , Dorset . Un hijo nació el 26 de diciembre, llamado Jan Laurens (más tarde conocido como John). En 1929, van der Post regresó a Sudáfrica para trabajar para Cape Times , un periódico de Ciudad del Cabo , donde "Por el momento, Marjorie y yo vivimos en la pobreza más extrema que existe", escribió en su diario. Comenzó a asociarse con bohemios e intelectuales que se oponían a James Hertzog ( Primer Ministro ) y a la política blanca sudafricana.. En un artículo titulado 'Sudáfrica en el crisol', que aclaró sus puntos de vista sobre el problema racial de Sudáfrica, dijo: "El sudafricano blanco nunca ha creído conscientemente que el nativo debería llegar a ser su igual". Sin embargo, predijo que "el proceso de nivelación e intermezcla debe acelerarse continuamente ... la futura civilización de Sudáfrica, creo, no es ni negra ni blanca, sino marrón". [ cita requerida ]

La influencia de Bloomsbury [ editar ]

En 1931, van der Post regresó a Inglaterra. Su amigo Plomer había sido publicado por Hogarth Press , una empresa dirigida por el matrimonio Leonard Woolf y la novelista Virginia Woolf . Los Woolf eran miembros del grupo literario y artístico de Bloomsbury y, a través de las presentaciones de Plomer, van der Post también conoció a figuras como Arthur Waley , JM Keynes y EM Forster . [ cita requerida ]

En 1934, los Woolf publicaron la primera novela de van der Post. Llamado En una provincia , retrató las trágicas consecuencias de una Sudáfrica dividida racial e ideológicamente. Más tarde ese año, decidió convertirse en un granjero de productos lácteos y, posiblemente con la ayuda de la poeta Lilian Bowes Lyon , adinerada e independiente , compró Colley Farm, cerca de Tetbury , Gloucestershire , con Lilian como su vecina. Allí dividió su tiempo entre las necesidades de las vacas y visitas ocasionales a Londres, donde era corresponsal de periódicos sudafricanos. Consideraba que esta era una fase sin rumbo en su vida que reflejaba la lenta deriva de Europa hacia la guerra. [ cita requerida ]

En 1936 hizo cinco viajes a Sudáfrica y durante un viaje conoció y se enamoró de Ingaret Giffard (1902-1997), una actriz y escritora inglesa cuatro años mayor que él. Más tarde, ese mismo año, su esposa Marjorie dio a luz a un segundo hijo, una hija llamada Lucia, y en 1938 envió a su familia de regreso a Sudáfrica. Cuando comenzó la Segunda Guerra Mundial en 1939, se encontró dividido entre Inglaterra y Sudáfrica, su nuevo amor y su familia; su carrera estaba en un callejón sin salida, y estaba deprimido, a menudo bebiendo mucho. [ cita requerida ]

Servicio de guerra [ editar ]

Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, en mayo de 1940, van der Post se ofreció como voluntario para el ejército británico y al completar el entrenamiento de oficiales en enero de 1941 fue enviado a África Oriental en el Cuerpo de Inteligencia como capitán . Allí se incorporó a la Fuerza Gideon del general Wingate , a la que se le encomendó la tarea de restaurar al emperador Haile Selassie en su trono en Abisinia . Su unidad condujo a 11.000 camellos a través de terrenos montañosos difíciles y fue recordado por ser un excelente cuidador de los animales. En marzo, contrajo malaria y fue enviado a Palestina para recuperarse. [cita requerida ]

A principios de 1942, cuando las fuerzas japonesas invadieron el sudeste asiático , van der Post fue transferido a las fuerzas aliadas en las Indias Orientales Holandesas (Indonesia), debido a sus habilidades en el idioma holandés. Según su propia declaración, se le dio el mando de la Misión Especial 43, cuyo propósito era organizar la evacuación encubierta de la mayor cantidad posible de personal aliado, después de la rendición de Java . [ cita requerida ]

El 20 de abril de 1942 se rindió a los japoneses. Fue llevado a campos de prisioneros primero en Sukabumi y luego a Bandung . Van der Post fue famoso por su trabajo en el mantenimiento de la moral de los prisioneros de muchas nacionalidades diferentes. Junto con otros, organizó una "universidad de campamento" con cursos desde alfabetización básica hasta historia antigua estándar, y también organizó una granja de campamento para complementar las necesidades nutricionales. También podía hablar algo de japonés básico, lo que le ayudó mucho. Una vez, deprimido, escribió en su diario: "Es una de las cosas más duras de esta vida carcelaria: la tensión que provoca estar continuamente en el poder de personas que están medio cuerdas y viven en un crepúsculo de razón y humanidad. " Escribió sobre sus experiencias en prisión en A Bar of Shadow.(1954), La semilla y el sembrador (1963) y La noche de la luna nueva (1970). La directora de cine japonesa Nagisa Oshima basó su película Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1982) en los dos últimos de estos libros. [3]

Tras la rendición de Japón , mientras sus compañeros prisioneros de guerra eran repatriados, van der Post decidió permanecer en Java y, el 15 de septiembre de 1945, se unió al almirante Wilfrid Patterson en el HMS Cumberland para la rendición oficial de los japoneses en Java a las fuerzas británicas que representaban a los Estados Unidos. Aliados.

Van der Post pasó dos años ayudando a mediar entre los nacionalistas indonesios y los miembros del gobierno colonial holandés. Se había ganado la confianza de los líderes nacionalistas como Mohammad Hatta y Sukarno y advirtió tanto al primer ministro Clement Attlee como al comandante supremo aliado en el sudeste asiático , el almirante Lord Louis Mountbatten , a quien conoció en Londres en octubre de 1945, que el país estaba en a punto de explotar. Van der Post fue a La Haya para repetir su advertencia directamente al gabinete holandés. En noviembre de 1946, las fuerzas británicas se retiraron y van der Post se convirtió en agregado militar del consulado británico en Batavia.. By 1947, after he had returned to England, the Indonesian Revolution had begun. That same year, van der Post retired from the army and was made a CBE. The events of these early post-war years in Java are examined in his memoir The Admiral's Baby (1996).

Post-war life[edit]

With the war over and his business with the army concluded, van der Post returned to South Africa in late 1947 to work at the Natal Daily News, but with the election victory of the National Party and the onset of apartheid he came back to London. He later published a critique of apartheid (The Dark Eye in Africa, 1955), basing many of his insights on his developing interest in psychology. In May 1949 he was commissioned by the Colonial Development Corporation (CDC) to "assess the livestock capacities of the uninhabited Nyika and Mulanje plateaux of Nyasaland" (now part of Malawi).

Around this time he divorced Marjorie, and on 13 October 1949, married Ingaret Giffard.

In the early 1950s, when he was 46, he sexually exploited (statutory rape) Bonny Kohler-Baker, the 14-year-old daughter of a prominent South African wine-making family, who had been entrusted to his care during a sea voyage. She became pregnant, and although he sent her a small stipend, he never publicly acknowledged the daughter born of the relationship.[4][5]

He went on honeymoon with Ingaret to Switzerland, where his new wife introduced him to Carl Jung. Jung was to have probably a greater influence upon him than anybody else, and he later said that he had never met anyone of Jung's stature. He continued to work on a travel book about his Nyasaland adventures called Venture to the Interior, which became an immediate best-seller in the US and Europe on its publication in 1952.[citation needed]

In 1950 Lord Reith (head of the CDC) asked van der Post to head an expedition to Bechuanaland (now part of Botswana), to see the potential of the remote Kalahari Desert for cattle ranching. There van der Post for the first time met the hunter-gatherer bush people known as Bushmen or San. He repeated the journey to the Kalahari in 1952. In 1953 he published his third book, The Face Beside the Fire, a semi-autobiographical novel about a psychologically "lost" artist in search of his soul and soul-mate, which clearly shows Jung's influence on his thinking and writing.

Flamingo Feather (1955) was an anti-communist novel in the guise of a Buchanesque adventure story, about a Soviet plot to take over South Africa. It sold very well. Alfred Hitchcock planned to film the book, but lost support from South African authorities and gave up the idea. Penguin Books kept Flamingo Feather in print until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In 1955 the BBC commissioned van der Post to return to the Kalahari in search of the Bushmen, a journey that turned into a six-part television documentary series in 1956. In 1958 his best known book was published under the same title as the BBC series: The Lost World of the Kalahari. He followed this in 1961 by The Heart of the Hunter, derived from Specimens of Bushman Folklore (1910), collected by Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd, and Mantis and His Hunter, collected by Dorothea Bleek.[6]

Van der Post described the Bushmen as the original natives of southern Africa, outcast and persecuted by all other races and nationalities. He said they represented the "lost soul" of all mankind, a type of noble savage myth. This mythos of the Bushmen inspired the colonial government to create the Central Kalahari Game Reserve in 1961 to guarantee their survival, and the reserve became a part of settled law when Botswana was created in 1966.

Later years[edit]

Van der Post had become a respected television personality, had introduced the world to the Kalahari Bushmen, and was considered an authority on Bushman folklore and culture. "I was compelled towards the Bushmen," he said, "like someone who walks in his sleep, obedient to a dream of finding in the dark what the day has denied him." Over the next fifteen years he had a steady stream of publications, including the two books drawn from his war experiences (see above), a travel book called A Journey into Russia (1964) describing a long trip through the Soviet Union, and two novels of adventure set on the fringes of the Kalarahi desert, A Story Like the Wind (1972) and its sequel A Far-Off Place (1974). The latter volumes, about four young people, two of them San, caught up in violent events on the borders of 1970s Rhodesia, became popular as class readers in secondary schools. In 1972 there was a BBC television series about his 16-year friendship with Jung, who died in 1961, which was followed by the book Jung and the Story of our Time (1976).

Ingaret and he moved to Aldeburgh, Suffolk, where they became involved with a circle of friends that included an introduction to Prince Charles, whom he then took on a safari to Kenya in 1977 and with whom he had a close and influential friendship for the rest of his life. Also in 1977, together with Ian Player, a South African conservationist, he created the first World Wilderness Congress in Johannesburg. In 1979 his Chelsea neighbor Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister and she called on his advice with matters dealing with southern Africa, notably the Rhodesia settlement of 1979–80. In 1981 he was given a Knighthood.

In 1982 he fell and injured his back and used the hiatus from tennis and skiing to write an autobiography called Yet Being Someone Other (1982), which discussed his love of the sea and his journey to Japan with Plomer in 1926. (His affection for that country and its people, despite his wartime experiences, had first been explored in 1968 in his Portrait of Japan.) By now Ingaret was slipping into senility, and he spent much time with Frances Baruch, an old friend. In 1984 his son John (who had gone on to be an engineer in London) died, and van der Post spent time with his youngest daughter Lucia and her family.[citation needed]

In old age Sir Laurens van der Post was involved with many projects, from the worldwide conservationist movement, to setting up a centre of Jungian studies in Cape Town. A Walk with a White Bushman (1986), the transcript of a series of interviews, gives a taste of his appeal as a conversationalist. In 1996, he tried to prevent the eviction of the Bushmen from their homeland in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, which had been set up for that purpose, but ironically it was his work in the 1950s to promote the land for cattle ranching that led to their eventual removal. In October 1996 he published The Admiral's Baby, describing the events in Java at the end of the war. His 90th birthday celebration was spread over five days in Colorado, with a "this is your life" type event with friends from every period of his life. A few days later, on 16 December 1996, after whispering in Afrikaans "die sterre" (the stars), he died. The funeral took place on 20 December in London, attended by Zulu chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, Prince Charles, Margaret Thatcher, and many friends and family.[7] His ashes were buried in a special memorial garden at Philippolis on 4 April 1998. Ingaret died five months after him on 5 May 1997.

Posthumous controversy[edit]

After his death a number of writers questioned the accuracy of van der Post's claims about his life.[8] His reputation as a "modern sage" and "guru" was questioned, and journalists published examples of van der Post's embellishing the truth in his memoirs and travel books,[8] most notably J. D. F. Jones, who in his authorised biography Teller of Many Tales: The Lives of Laurens van der Post (2001) claimed that van der Post was "a fraud, a fantasist, a liar, a serial adulterer and a paternalist. He falsified his Army record and inflated his own importance at every possible opportunity."[7][9][10] A rebuttal was published by Christopher Booker (van der Post's ODNB biographer and friend) in The Spectator.[11]

Selected works[edit]

For a complete list see External links.

- In a Province; novel (1934; reprinted 1953).

- Venture to the Interior; travel (1952).

- The Face Beside the Fire; novel (1953).

- A Bar of Shadow; novella (1954).

- Flamingo Feather; novel (1955).

- The Dark Eye in Africa; politics, psychology (1955).

- The Lost World of the Kalahari; travel (1958) [BBC 6-part TV series, 1956].

- The Heart of the Hunter; travel, folklore (1961).

- The Seed and the Sower; three novellas (1963).

- A Journey into Russia (US title: A View of All the Russias); travel (1964).

- A Portrait of Japan; travel (1968).

- The Night of the New Moon (US title: The Prisoner and the Bomb); wartime memoirs (1970).

- A Story Like the Wind; novel (1972).

- A Far-Off Place; novel, sequel to the above (1974).

- Jung and the Story of Our Time; psychology, memoir (1975).

- Yet Being Someone Other; memoir, travel (1982).

- A Walk with A White Bushman; interview-transcripts (1986).

- The Admiral's Baby; memoir (1996).

Movies[edit]

Film adaptations of his books.

- Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983)—based on The Seed and the Sower (1963) and The Night of the New Moon (1970), about his experience as a prisoner of war.[3] Directed by Nagisa Oshima and starring David Bowie.

- A Far Off Place (1993)—based on A Far-Off Place (1974) and A Story Like the Wind (1972).

References[edit]

- ^ "A Prophet Out of Africa". The Times. 17 December 1996. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ Campbell, Roy; van der Post, Laurens & Plomer, William (1926). Voorslag 1–3: A Magazine of South African Life and Art. ISBN 0-86980-423-5.

- ^ a b Dennis, Jon (1 March 2012). "Readers Recommend: Songs about Books". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Smith, Dinitia (3 August 2002). "Master Storyteller or Master Deceiver?". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ Bennett, Catherine (29 November 2020). "The Crown isn't making the royal family look bad. They do a fine job of that themselves". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ van der Post, Laurens (1961). The Heart of the Hunter. London: Hogarth Press. Introduction.

- ^ a b Smith, Dinitia (3 August 2003). "Master Storyteller or Master Deceiver?". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ a b Booker, Christopher (May 2005). "Post, Sir Laurens Jan van der (1906–1996)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (4 February 2001). "Secret life of royal guru revealed". The Observer. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ "The guru who got away with it". The Daily Telegraph. 22 September 2001. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Booker, Christopher (20 October 2001). "Small lies and the greater truth". The Spectator. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Carpenter, Frederic I. (1969). Laurens Van Der Post. New York: Twayne Publishers.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laurens van der Post. |

- Complete published works by or about LvdP

- Laurens van der Post at IMDb

- Images of LvdP, from the National Portrait Gallery.