| Nueva Orleans La Nouvelle-Orléans ( francés ) | |

|---|---|

| Ciudad de nueva orleans | |

Desde arriba, de izquierda a derecha: Central Business District , un tranvía en Nueva Orleans, St. Louis Cathedral en Jackson Square , Bourbon Street , Mercedes-Benz Superdome , University of New Orleans , Crescent City Connection | |

| Apodo (s): "The Crescent City", "The Big Easy", "The City That Care Forgot", "NOLA", "The City of Yes", "Hollywood South" | |

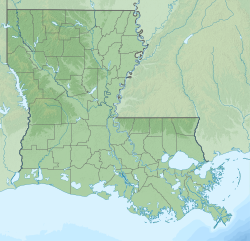

Ubicación dentro de Louisiana | |

| Coordenadas: 29.95 ° N 90.08 ° W Coordenadas : 29.95 ° N 90.08 ° W29°57′N 90°05′W / 29°57′N 90°05′W / | |

| País | Estados Unidos |

| Expresar | Luisiana |

| Parroquia | Orleans |

| Fundado | 1718 |

| Nombrado para | Felipe II, duque de Orleans (1674-1723) |

| Gobierno | |

| • Tipo | Alcalde-consejo |

| • Alcalde | LaToya Cantrell ( D ) |

| • Consejo | Ayuntamiento de Nueva Orleans |

| Área[1] | |

| • Ciudad-parroquia consolidada | 349,85 millas cuadradas (906,10 km 2 ) |

| • Tierra | 169,42 millas cuadradas (438,80 km 2 ) |

| • Agua | 180,43 millas cuadradas (467,30 km 2 ) |

| • Metro | 3.755,2 millas cuadradas (9.726,6 km 2 ) |

| Elevación | −6,5 a 20 pies (−2 a 6 m) |

| Población ( 2010 ) [2] | |

| • Ciudad-parroquia consolidada | 343,829 |

| • Estimación (2019) [3] | 390.144 |

| • Densidad | 2.029 / millas cuadradas (783 / km 2 ) |

| • Metro | 1,270,530 (Estados Unidos: 45 ) |

| Demonym (s) | Nueva Orleans |

| Zona horaria | UTC-6 ( CST ) |

| • Verano ( DST ) | UTC-5 ( CDT ) |

| Código (s) de área | 504 |

| Código FIPS | 22-55000 |

| ID de función GNIS | 1629985 |

| Sitio web | nola.gov |

New Orleans ( / ɔr l ( i ) ə n z , ɔr l i n z / , [4] [5] a nivel local / ɔr l ə n z / ; en francés : La Nouvelle-Orleans [la nuvɛlɔʁleɑ̃] ( escuchar ) ) es una ciudad-parroquia consolidada ubicada a lo largo del río Mississippi en la región sureste del estado estadounidense de Louisiana . Con una población estimada de 390.144 en 2019, [6] es la ciudad más poblada de Louisiana. Sirviendo como un puerto importante , Nueva Orleans se considera un centro económico y comercial para la región más amplia de la Costa del Golfo de los Estados Unidos .

Nueva Orleans es mundialmente conocida por su música distintiva , cocina criolla , dialectos únicos y sus celebraciones y festivales anuales, sobre todo el Mardi Gras . El corazón histórico de la ciudad es el Barrio Francés , conocido por su arquitectura criolla francesa y española y su vibrante vida nocturna a lo largo de Bourbon Street . La ciudad ha sido descrita como la "más singular" [7] en los Estados Unidos, [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] debido en gran parte a su herencia multicultural y multilingüe. [13]Además, Nueva Orleans ha sido cada vez más conocida como "Hollywood South" debido a su papel destacado en la industria del cine y en la cultura pop. [14] [15]

Fundada en 1718 por colonos franceses, Nueva Orleans fue una vez la capital territorial de la Luisiana francesa antes de ser comercializada a los Estados Unidos en la Compra de Luisiana de 1803. Nueva Orleans en 1840 fue la tercera ciudad más poblada de los Estados Unidos, [16] y fue la ciudad más grande del sur de Estados Unidos desde la era Antebellum hasta después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial . Históricamente, la ciudad ha sido muy vulnerable a las inundaciones , debido a sus altas precipitaciones, baja elevación, drenaje natural deficiente y proximidad a múltiples cuerpos de agua. Las autoridades estatales y federales han instalado un complejo sistema de diques y bombas de drenaje.en un esfuerzo por proteger la ciudad. [17]

Nueva Orleans se vio gravemente afectada por el huracán Katrina en agosto de 2005, que inundó más del 80% de la ciudad, mató a más de 1.800 personas y desplazó a miles de residentes, lo que provocó una disminución de la población de más del 50%. [18] Desde Katrina, los grandes esfuerzos de reurbanización han llevado a un repunte en la población de la ciudad. Se han expresado preocupaciones sobre la gentrificación , los nuevos residentes que compran propiedades en comunidades anteriormente unidas y el desplazamiento de residentes de mucho tiempo. [19]

La ciudad y la parroquia de Orleans (en francés : paroisse d'Orléans ) son colindantes. [20] A partir de 2017, Orleans Parish es la tercera parroquia más poblada de Louisiana, detrás de East Baton Rouge Parish y la vecina Jefferson Parish . [21] La ciudad y la parroquia están limitadas por la parroquia de St. Tammany y el lago Pontchartrain al norte, la parroquia de St. Bernard y el lago Borgne al este, la parroquia de Plaquemines al sur y la parroquia de Jefferson al sur y al oeste.

La ciudad ancla el área metropolitana más grande del Gran Nueva Orleans , que tenía una población estimada de 1.270.530 en 2019. [22] El Gran Nueva Orleans es el área estadística metropolitana más poblada de Louisiana y la 45.a MSA más poblada de los Estados Unidos. [23]

Etimología y apodos

La ciudad lleva el nombre del duque de Orleans , que reinó como regente de Luis XV de 1715 a 1723. [24] Tiene varios apodos:

- Crescent City , en alusión al curso del río Bajo Mississippi alrededor y a través de la ciudad. [25]

- The Big Easy , posiblemente una referencia de los músicos de principios del siglo XX a la relativa facilidad para encontrar trabajo allí. [26] [27]

- The City that Care Forgot , utilizada desde al menos 1938, [28] y se refiere a la naturaleza aparentemente tranquila y despreocupada de los residentes. [27]

Historia

Era colonial franco-española

La Nouvelle-Orléans (Nueva Orleans) fue fundada en la primavera de 1718 (el 7 de mayo se ha convertido en la fecha tradicional para conmemorar el aniversario, pero se desconoce el día real) [29] por la Compañía francesa de Mississippi , bajo la dirección de Jean- Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville , en tierras habitadas por Chitimacha . Lleva el nombre de Felipe II, duque de Orleans , que en ese momento era regente del Reino de Francia . [24] Su título proviene de la ciudad francesa de Orleans . La colonia francesa de Luisiana fue cedida al Imperio español en el1763 Tratado de París , tras la derrota de Francia por Gran Bretaña en la Guerra de los Siete Años . Durante la Guerra de Independencia de los Estados Unidos , Nueva Orleans fue un puerto importante para el contrabando de ayuda a los revolucionarios estadounidenses y para el transporte de equipos y suministros militares por el río Mississippi . A partir de la década de 1760, los filipinos comenzaron a establecerse en Nueva Orleans y sus alrededores. [30] Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Conde de Gálvez dirigió con éxito una campaña sureña contra los británicos desde la ciudad en 1779. [31] Nueva Orleans (el nombre de Nueva Orleans en español ) [32] permaneció bajo control español hasta 1803, cuando volvió brevemente al dominio francés . Casi toda la arquitectura sobreviviente del siglo XVIII del Vieux Carré ( Barrio Francés ) data del período español, con la excepción del Antiguo Convento de las Ursulinas . [33]

Como colonia francesa, Luisiana enfrentó luchas con numerosas tribus nativas americanas , una de las cuales fue la Natchez en el sur de Mississippi. En la década de 1720 se desarrollaron problemas entre los franceses y los indios Natchez que se llamarían Guerra Natchez o Revuelta Natchez . Aproximadamente 230 colonos franceses murieron y la joven colonia fue reducida a cenizas. [34]

El conflicto entre las dos partes fue un resultado directo de que el teniente d'Etcheparre (más comúnmente conocido como Sieur de Chépart ), el comandante en el asentamiento cerca de Natchez, decidió en 1729 que los indios Natchez debían entregar tanto sus tierras de cultivo cultivadas como sus tierras. ciudad de White Apple a los franceses. Los Natchez fingieron rendirse y de hecho trabajaron para los franceses en el juego de la caza, pero tan pronto como fueron armados, contraatacaron y mataron a varios hombres, lo que provocó que los colonos huyeran río abajo a Nueva Orleans. Los colonos que huían buscaron protección de lo que temían que pudiera ser una incursión indígena en toda la colonia. Los Natchez, sin embargo, no siguieron adelante después de su ataque sorpresa, dejándolos lo suficientemente vulnerables para el gobernador designado por el rey Luis XV.Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville para recuperar el asentamiento. [ cita requerida ]

Las relaciones con los indios de Luisiana, un problema heredado de Bienville, siguieron siendo motivo de preocupación para el próximo gobernador, el marqués de Vaudreuil . A principios de la década de 1740, los comerciantes de las Trece Colonias cruzaron a las Montañas Apalaches. Las tribus nativas americanas ahora operarían dependiendo de cuál de los varios colonos europeos los beneficiaría más. Varias de estas tribus y especialmente Chickasaw y Choctaw intercambiarían bienes y regalos por su lealtad. [35]

La economía emitida en la colonia, que continuó bajo Vaudreuil, resultó en muchas incursiones por parte de tribus nativas americanas, aprovechando la debilidad francesa. En 1747 y 1748, Chickasaw atacaría a lo largo de la orilla este del Mississippi hasta el sur hasta Baton Rouge. Estas redadas a menudo obligarían a los residentes de la Luisiana francesa a refugiarse en Nueva Orleans propiamente dicha. [ cita requerida ]

La imposibilidad de encontrar mano de obra era el problema más urgente en la joven colonia. Los colonos recurrieron a los esclavos africanos para rentabilizar sus inversiones en Luisiana. A finales de la década de 1710, el comercio transatlántico de esclavos importó africanos esclavizados a la colonia. Esto llevó al envío más grande en 1716, donde aparecieron varios barcos comerciales con esclavos como carga para los residentes locales en un lapso de un año. [ cita requerida ]

En 1724, la gran cantidad de negros en Luisiana impulsó la institucionalización de las leyes que gobiernan la esclavitud dentro de la colonia. [36] Estas leyes requerían que los esclavos fueran bautizados en la fe católica romana, que los esclavos se casaran en la iglesia y no les otorgaban derechos legales. La ley de esclavos formada en la década de 1720 se conoce como el Código Noir , que se desangraría también en el período anterior a la guerra del sur de Estados Unidos. La cultura esclavista de Luisiana tenía su propia sociedad afro-criolla distintiva que recurría a las culturas pasadas y la situación de los esclavos en el Nuevo Mundo. Afro-criollo estuvo presente en las creencias religiosas y el dialecto criollo de Luisiana. La religión más asociada con este período se llamó vudú . [37] [38]

En la ciudad de Nueva Orleans, una mezcla inspiradora de influencias extranjeras creó un crisol de culturas que todavía se celebra en la actualidad. Al final de la colonización francesa en Luisiana, Nueva Orleans fue reconocida comercialmente en el mundo atlántico. Sus habitantes comerciaban a través del sistema comercial francés. Nueva Orleans fue un centro para este comercio tanto física como culturalmente porque sirvió como punto de salida al resto del mundo para el interior del continente norteamericano.

En un caso, el gobierno francés estableció una sala capitular de hermanas en Nueva Orleans. Las hermanas Ursulinas después de ser patrocinadas por la Compañía de Indias , fundaron un convento en la ciudad en 1727. [39] Al final de la época colonial, la Academia Ursulina mantenía una casa de setenta internos y cien estudiantes de día. Hoy en día, numerosas escuelas de Nueva Orleans pueden rastrear su linaje desde esta academia.

Otro ejemplo notable es el plano y la arquitectura que aún distinguen a Nueva Orleans en la actualidad. La Luisiana francesa tuvo arquitectos tempranos en la provincia que fueron entrenados como ingenieros militares y ahora fueron asignados a diseñar edificios gubernamentales. Pierre Le Blond de Tour y Adrien de Pauger , por ejemplo, planearon muchas de las primeras fortificaciones, junto con el plano de las calles de la ciudad de Nueva Orleans. [40] Después de ellos, en la década de 1740, Ignace François Broutin, como ingeniero en jefe de Louisiana, reelaboró la arquitectura de Nueva Orleans con un extenso programa de obras públicas.

Los políticos franceses en París intentaron establecer normas políticas y económicas para Nueva Orleans. Actuó de forma autónoma en gran parte de sus aspectos culturales y físicos, pero también se mantuvo en comunicación con las tendencias extranjeras.

Después de que los franceses renunciaron a West Louisiana a los españoles, los comerciantes de Nueva Orleans intentaron ignorar el dominio español e incluso restablecer el control francés sobre la colonia. Los ciudadanos de Nueva Orleans celebraron una serie de reuniones públicas durante 1765 para mantener a la población en oposición al establecimiento del dominio español. Las pasiones anti-españolas en Nueva Orleans alcanzaron su nivel más alto después de dos años de administración española en Luisiana. El 27 de octubre de 1768, una turba de residentes locales, disparó las armas que custodiaban Nueva Orleans y tomó el control de la ciudad de manos de los españoles . [41]La rebelión organizó un grupo para zarpar hacia París, donde se reunió con funcionarios del gobierno francés. Este grupo trajo consigo un largo memorial para resumir los abusos que la colonia había sufrido por parte de los españoles. El rey Luis XV y sus ministros reafirmaron la soberanía de España sobre Luisiana.

Era territorial de Estados Unidos

Napoleón vendió Luisiana (Nueva Francia) a los Estados Unidos en la Compra de Luisiana en 1803. [42] A partir de entonces, la ciudad creció rápidamente con la afluencia de estadounidenses, franceses , criollos y africanos . Los inmigrantes posteriores fueron irlandeses , alemanes , polacos e italianos . Las principales cosechas de azúcar y algodón se cultivaron con mano de obra esclava en grandes plantaciones cercanas .

Miles de refugiados de la Revolución Haitiana de 1804 , tanto blancos como personas libres de color ( affranchis o gens de couleur libres ), llegaron a Nueva Orleans; algunos trajeron a sus esclavos con ellos, muchos de los cuales eran africanos nativos o de ascendencia pura sangre. Mientras que el gobernador Claiborne y otros funcionarios querían mantener fuera a más negros libres , los criollos franceses querían aumentar la población de habla francesa. A medida que se permitió la entrada de más refugiados al Territorio de Orleans , también llegaron emigrados haitianos que habían ido por primera vez a Cuba . [43]Muchos de los francófonos blancos habían sido deportados por funcionarios en Cuba en represalia por los esquemas bonapartistas . [44]

Casi el 90 por ciento de estos inmigrantes se establecieron en Nueva Orleans. La migración de 1809 trajo a 2.731 blancos, 3.102 personas libres de color (de raza mixta europea y afrodescendiente) y 3.226 esclavos principalmente de ascendencia africana, duplicando la población de la ciudad. La ciudad se convirtió en un 63 por ciento de negros, una proporción mayor que el 53 por ciento de Charleston, Carolina del Sur . [43]

Batalla de Nueva Orleans

Durante la campaña final de la Guerra de 1812 , los británicos enviaron una fuerza de 11.000 en un intento de capturar Nueva Orleans. A pesar de grandes retos, el general Andrew Jackson , con el apoyo de la Armada de Estados Unidos , adoquinados juntos con éxito una fuerza de la milicia de Louisiana y Mississippi , del Ejército de EE.UU. habituales, un gran contingente de Tennessee milicia del estado, Kentucky frontera y locales corsarios (esta última dirigida por el pirata Jean Lafitte ), para derrotar decisivamente a los británicos , liderados por Sir Edward Pakenham , en elBatalla de Nueva Orleans el 8 de enero de 1815. [46]

Los ejércitos no se habían enterado del Tratado de Gante , que había sido firmado el 24 de diciembre de 1814 (sin embargo, el tratado no exigía el cese de hostilidades hasta después de que ambos gobiernos lo hubieran ratificado. El gobierno de Estados Unidos lo ratificó el 16 de febrero de 1815). ). Los combates en Luisiana habían comenzado en diciembre de 1814 y no terminaron hasta finales de enero, después de que los estadounidenses mantuvieran a raya a la Royal Navy durante un asedio de diez días a Fort St. Philip (la Royal Navy pasó a capturar Fort Bowyer cerca de Mobile , antes de los comandantes recibieron noticias del tratado de paz). [46]

Puerto

Como puerto , Nueva Orleans jugó un papel importante durante la era anterior a la guerra en el comercio de esclavos en el Atlántico . El puerto manejaba mercancías para la exportación desde el interior y mercancías importadas de otros países, que se almacenaban y trasladaban en Nueva Orleans a embarcaciones más pequeñas y se distribuían a lo largo de la cuenca del río Mississippi. El río estaba lleno de barcos de vapor, botes y veleros. A pesar de su papel en el comercio de esclavos , Nueva Orleans en ese momento también tenía la comunidad más grande y próspera de personas de color libres de la nación, que a menudo eran propietarios educados de clase media. [47] [48]

Empequeñeciendo a las otras ciudades del sur de Antebellum , Nueva Orleans tenía el mercado de esclavos más grande de Estados Unidos. El mercado se expandió después de que Estados Unidos puso fin al comercio internacional en 1808. Dos tercios de más de un millón de esclavos traídos al sur profundo llegaron a través de la migración forzada en el comercio de esclavos doméstico . El dinero generado por la venta de esclavos en el Alto Sur se ha estimado en el 15 por ciento del valor de la economía de cultivos básicos. Los esclavosfueron valorados colectivamente en 500 millones de dólares. El comercio generó una economía auxiliar: transporte, vivienda y ropa, tarifas, etc., estimada en el 13,5% del precio por persona, que asciende a decenas de miles de millones de dólares (dólares de 2005, ajustados por inflación) durante el período anterior a la guerra . Orleans como principal beneficiario. [49]

Según el historiador Paul Lachance,

la adición de inmigrantes blancos [de Saint-Domingue] a la población criolla blanca permitió que los francófonos siguieran siendo la mayoría de la población blanca hasta casi 1830. Si una proporción sustancial de personas libres de color y esclavos no habían hablado también francés, sin embargo , la comunidad gala se habría convertido en una minoría de la población total ya en 1820. [50]

Después de la compra de Luisiana, numerosos angloamericanos emigraron a la ciudad. La población se duplicó en la década de 1830 y para 1840, Nueva Orleans se había convertido en la ciudad más rica y la tercera más poblada del país, después de Nueva York y Baltimore . [51] Los inmigrantes alemanes e irlandeses comenzaron a llegar en la década de 1840, trabajando como trabajadores portuarios. En este período, la legislatura estatal aprobó más restricciones sobre las manumisiones de esclavos y prácticamente la puso fin en 1852. [52]

En la década de 1850, los francófonos blancos seguían siendo una comunidad intacta y vibrante en Nueva Orleans. Mantuvieron la instrucción en francés en dos de los cuatro distritos escolares de la ciudad (todos atendían a estudiantes blancos). [53] En 1860, la ciudad tenía 13.000 personas libres de color ( gens de couleur libres ), la clase de personas libres, en su mayoría mestizas, que se expandió en número durante el dominio francés y español. Establecieron algunas escuelas privadas para sus hijos. El censo registró al 81 por ciento de las personas de color libres como mulatos , un término utilizado para cubrir todos los grados de raza mixta. [52]En su mayoría parte del grupo francófono, constituían la clase artesana, educada y profesional de los afroamericanos. La masa de negros todavía estaba esclavizada, trabajando en el puerto, en el servicio doméstico, en la artesanía y, sobre todo, en las numerosas y grandes plantaciones de caña de azúcar circundantes .

Después de crecer en un 45 por ciento en la década de 1850, en 1860, la ciudad tenía casi 170.000 habitantes. [54] Había crecido en riqueza, con un "ingreso per cápita [que] era el segundo en la nación y el más alto en el Sur". [54] La ciudad tenía un papel como la "puerta de entrada comercial principal para el sector medio en auge de la nación". [54] El puerto era el tercero más grande de la nación en términos de tonelaje de mercancías importadas, después de Boston y Nueva York, manejando 659.000 toneladas en 1859. [54]

Era de la Guerra Civil y la Reconstrucción

Como temía la élite criolla, la Guerra Civil estadounidense cambió su mundo. En abril de 1862, tras la ocupación de la ciudad por la Union Navy tras la Batalla de Forts Jackson y St. Philip , las fuerzas del Norte ocuparon la ciudad. General Benjamin F. Butler, un abogado respetado de Massachusetts que sirve en la milicia de ese estado, fue nombrado gobernador militar. Los residentes de Nueva Orleans que apoyaban a la Confederación lo apodaron "Bestia" Butler, debido a una orden que emitió. Después de que sus tropas habían sido asaltadas y hostigadas en las calles por mujeres que aún eran leales a la causa confederada, su orden advirtió que tales sucesos futuros darían lugar a que sus hombres trataran a esas mujeres como a las que "ejercen su afición en las calles", lo que implica que lo harían trata a las mujeres como prostitutas. Los relatos de esto se difundieron ampliamente. También llegó a ser llamado "Cucharas" Mayordomo por el presunto saqueo que hicieron sus tropas mientras ocupaban la ciudad, tiempo durante el cual él mismo supuestamente robó cubiertos de plata. [ cita requerida ]

De manera significativa, Butler abolió la enseñanza del idioma francés en las escuelas de la ciudad. Las medidas estatales en 1864 y, después de la guerra, en 1868 fortalecieron aún más la política de solo inglés impuesta por los representantes federales. Con el predominio de angloparlantes, ese idioma ya se había convertido en dominante en los negocios y el gobierno. [53] A finales del siglo XIX, el uso del francés se había desvanecido. También estuvo bajo la presión de inmigrantes irlandeses, italianos y alemanes. [55] Sin embargo, en 1902 "una cuarta parte de la población de la ciudad hablaba francés en las relaciones cotidianas normales, mientras que otras dos cuartas partes eran capaces de entender el idioma perfectamente", [56] y hasta 1945, muchos las ancianas criollas no hablaban inglés. [57]El último periódico importante en lengua francesa, L'Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans (Abeja de Nueva Orleans), dejó de publicarse el 27 de diciembre de 1923, después de noventa y seis años. [58] Según algunas fuentes, Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continuó hasta 1955. [59]

Como la ciudad fue capturada y ocupada al principio de la guerra, se salvó de la destrucción a través de la guerra sufrida por muchas otras ciudades del sur de Estados Unidos . El Ejército de la Unión finalmente extendió su control hacia el norte a lo largo del río Mississippi y a lo largo de las áreas costeras. Como resultado, la mayor parte de la parte sur de Luisiana estaba originalmente exenta de las disposiciones liberadoras de la " Proclamación de Emancipación " de 1863 emitida por el presidente Abraham Lincoln . Un gran número de ex esclavos rurales y algunas personas libres de color de la ciudad se ofrecieron como voluntarios para los primeros regimientos de tropas negras en la guerra. Dirigido por el general de brigada Daniel Ullman(1810-1892), del 78º Regimiento de la Milicia de Voluntarios del Estado de Nueva York, se les conocía como el " Cuerpo de África ". Si bien ese nombre había sido utilizado por una milicia antes de la guerra, ese grupo estaba compuesto por personas de color libres . El nuevo grupo estaba formado principalmente por antiguos esclavos. Fueron complementados en los dos últimos años de la guerra por las tropas de color de los Estados Unidos recientemente organizadas , que desempeñaron un papel cada vez más importante en la guerra. [60]

La violencia en todo el sur, especialmente los disturbios de Memphis de 1866 seguidos por los disturbios de Nueva Orleans el mismo año, llevaron al Congreso a aprobar la Ley de Reconstrucción y la Decimocuarta Enmienda , extendiendo las protecciones de la ciudadanía plena a los libertos y las personas de color libres. Luisiana y Texas quedaron bajo la autoridad del " Quinto Distrito Militar " de los Estados Unidos durante la Reconstrucción. Luisiana fue readmitida en la Unión en 1868. Su Constitución de 1868 otorgó el sufragio universal masculino y estableció la educación pública universal.. Tanto negros como blancos fueron elegidos para cargos locales y estatales. En 1872, el vicegobernador PBS Pinchback , quien era de raza mixta , sucedió a Henry Clay Warmouth durante un breve período como gobernador republicano de Luisiana , convirtiéndose en el primer gobernador de ascendencia africana de un estado estadounidense (el próximo afroamericano en servir como gobernador de una El estado estadounidense fue Douglas Wilder , elegido en Virginia en 1989). Nueva Orleans operó un sistema de escuelas públicas racialmente integrado durante este período.

Los daños causados por la guerra a los diques y las ciudades a lo largo del río Mississippi afectaron negativamente a los cultivos y el comercio del sur. El gobierno federal contribuyó a restaurar la infraestructura. La recesión financiera nacional y el pánico de 1873 afectaron negativamente a las empresas y desaceleraron la recuperación económica.

A partir de 1868, las elecciones en Luisiana estuvieron marcadas por la violencia, ya que los insurgentes blancos intentaron reprimir el voto de los negros e interrumpir las reuniones del Partido Republicano . La disputada elección de gobernador de 1872 resultó en conflictos que duraron años. La " Liga Blanca ", un grupo paramilitar insurgente que apoyaba al Partido Demócrata , se organizó en 1874 y operaba abiertamente, reprimiendo violentamente el voto negro y expulsando a los funcionarios republicanos. En 1874, en la Batalla de Liberty Place , 5.000 miembros de la Liga Blanca lucharon con la policía de la ciudad para hacerse cargo de las oficinas estatales del candidato demócrata a gobernador y las retuvieron durante tres días. En 1876, tales tácticas dieron como resultado que los demócratas blancos, los llamados Redentores , recuperando el control político de la legislatura estatal. El gobierno federal se rindió y retiró sus tropas en 1877, poniendo fin a la Reconstrucción .

Era de Jim Crow

Los demócratas blancos aprobaron las leyes Jim Crow , estableciendo la segregación racial en las instalaciones públicas. En 1889, la legislatura aprobó una enmienda constitucional que incorporaba una " cláusula del abuelo " que privaba efectivamente a los libertos así como a las personas propietarias de color manumitidas antes de la guerra. Al no poder votar, los afroamericanos no podían formar parte de jurados ni de cargos locales, y fueron excluidos de la política formal durante generaciones. El sur de Estados Unidos estaba gobernado por un Partido Demócrata blanco. Las escuelas públicas estaban segregadas racialmente y permanecieron así hasta 1960.

La gran comunidad de Nueva Orleans de personas de color libres , bien educadas, a menudo francófonas ( gens de couleur libres ), que habían sido libres antes de la Guerra Civil, luchó contra Jim Crow. Organizaron el Comité des Citoyens (Comité de Ciudadanos) para trabajar por los derechos civiles. Como parte de su campaña legal, reclutaron a uno de los suyos, Homer Plessy , para probar si la Ley de Automóviles Separados recientemente promulgada en Louisiana era constitucional. Plessy abordó un tren de cercanías que partía de Nueva Orleans hacia Covington, Louisiana , se sentó en el vagón reservado solo para blancos y fue arrestado. El caso resultante de este incidente, Plessy v. Ferguson , fue escuchado por la Corte Suprema de EE. UU.en 1896. El tribunal dictaminó que las acomodaciones " separadas pero iguales " eran constitucionales, lo que efectivamente defendía las medidas de Jim Crow.

En la práctica, las escuelas e instalaciones públicas afroamericanas carecían de fondos suficientes en todo el sur. El fallo de la Corte Suprema contribuyó a que este período fuera el punto más bajo de las relaciones raciales en Estados Unidos. La tasa de linchamientos de hombres negros fue alta en todo el sur, ya que otros estados también privaron de derechos a los negros y trataron de imponer a Jim Crow. También afloraron los prejuicios nativistas. El sentimiento anti-italiano en 1891 contribuyó al linchamiento de 11 italianos , algunos de los cuales habían sido absueltos del asesinato del jefe de policía. A algunos los mataron a tiros en la cárcel donde estaban detenidos. Fue el linchamiento masivo más grande en la historia de Estados Unidos. [61] [62]En julio de 1900, la ciudad fue arrasada por turbas blancas que se amotinaron después de que Robert Charles, un joven afroamericano, mató a un policía y escapó temporalmente. La turba lo mató a él ya unos 20 negros más; Siete blancos murieron en el conflicto que duró varios días, hasta que una milicia estatal lo reprimió.

A lo largo de la historia de Nueva Orleans, hasta principios del siglo XX, cuando los avances médicos y científicos mejoraron la situación, la ciudad sufrió repetidas epidemias de fiebre amarilla y otras enfermedades tropicales e infecciosas .

siglo 20

El cenit económico y poblacional de Nueva Orleans en relación con otras ciudades estadounidenses ocurrió en el período anterior a la guerra. Fue la quinta ciudad más grande del país en 1860 (después de Nueva York , Filadelfia , Boston y Baltimore ) y era significativamente más grande que todas las demás ciudades del sur. [63] Desde mediados del siglo XIX en adelante, el rápido crecimiento económico se trasladó a otras áreas, mientras que la importancia relativa de Nueva Orleans disminuyó constantemente. El crecimiento de los ferrocarriles y carreteras disminuyó el tráfico fluvial, desviando mercancías a otros corredores de transporte y mercados. [63] Miles de las personas de color más ambiciosas abandonaron el estado en la Gran Migración alrededorLa Segunda Guerra Mundial y después, muchos para destinos de la Costa Oeste . Desde finales del siglo XIX, la mayoría de los censos registraron que Nueva Orleans descendió en la lista de las ciudades estadounidenses más grandes (la población de Nueva Orleans siguió aumentando durante todo el período, pero a un ritmo más lento que antes de la Guerra Civil).

A mediados del siglo XX, los habitantes de Nueva Orleans reconocieron que su ciudad ya no era la principal zona urbana del sur . Para 1950, Houston , Dallas y Atlanta superaron en tamaño a Nueva Orleans, y en 1960 Miami eclipsó a Nueva Orleans, incluso cuando la población de esta última alcanzó su pico histórico. [63] Al igual que con otras ciudades estadounidenses más antiguas, la construcción de carreteras y el desarrollo suburbano atrajeron a los residentes del centro de la ciudad a viviendas más nuevas en el exterior. El censo de 1970 registró la primera disminución absoluta de la población desde que la ciudad pasó a formar parte de los Estados Unidos en 1803. El área metropolitana del Gran Nueva Orleanscontinuó expandiéndose en población, aunque más lentamente que otras ciudades importantes del Sun Belt . Si bien el puerto sigue siendo uno de los más grandes del país, la automatización y la contenedorización cuestan muchos puestos de trabajo. El antiguo papel de la ciudad como banquero del sur fue reemplazado por ciudades pares más grandes. La economía de Nueva Orleans siempre se había basado más en el comercio y los servicios financieros que en la manufactura, pero el sector manufacturero relativamente pequeño de la ciudad también se contrajo después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. A pesar de algunos éxitos en el desarrollo económico bajo las administraciones de DeLesseps "Chep" Morrison (1946-1961) y Victor "Vic" Schiro (1961-1970), la tasa de crecimiento metropolitana de Nueva Orleans fue consistentemente por detrás de las ciudades más vigorosas.

Movimiento de derechos civiles

Durante los últimos años de la administración de Morrison, y durante la totalidad de la de Schiro, la ciudad fue un centro del Movimiento de Derechos Civiles . La Conferencia de Liderazgo Cristiano del Sur se fundó en Nueva Orleans, y se llevaron a cabo sentadas en el mostrador del almuerzo en los grandes almacenes de Canal Street . Una serie prominente y violenta de enfrentamientos ocurrió en 1960 cuando la ciudad intentó la eliminación de la segregación escolar, luego del fallo de la Corte Suprema en Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Cuando Ruby Bridges, de seis años, integró la escuela primaria William Frantz en el noveno distrito, fue la primera niña de color en asistir a una escuela que anteriormente era completamente blanca en el sur. Mucha controversia precedió al Sugar Bowl de 1956 en el Tulane Stadium , cuando los Pitt Panthers , con el fullback afroamericano Bobby Grier en la lista, se enfrentaron a los Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets . [64] Hubo controversia sobre si a Grier se le debería permitir jugar debido a su raza, y si Georgia Tech incluso debería jugar debido a la oposición del gobernador de Georgia, Marvin Griffin , a la integración racial. [65] [66] [67]Después de que Griffin envió públicamente un telegrama a la Junta de Regentes del estado solicitando a Georgia Tech que no participara en eventos racialmente integrados, el presidente de Georgia Tech, Blake R Van Leer, rechazó la solicitud y amenazó con renunciar. El juego se desarrolló según lo planeado [68]

El éxito del Movimiento de Derechos Civiles en la aprobación federal de la Ley de Derechos Civiles de 1964 y la Ley de Derechos Electorales de 1965 renovó los derechos constitucionales, incluido el voto por los negros. Juntos, estos resultaron en los cambios de mayor alcance en la historia del siglo XX de Nueva Orleans. [69] Aunque la igualdad legal y civil se restableció a fines de la década de 1960, persistió una gran brecha en los niveles de ingresos y logros educativos entre las comunidades blancas y afroamericanas de la ciudad. [70]A medida que la clase media y los miembros más ricos de ambas razas abandonaron el centro de la ciudad, el nivel de ingresos de su población disminuyó y se volvió proporcionalmente más afroamericana. A partir de 1980, la mayoría afroamericana eligió principalmente a funcionarios de su propia comunidad. Lucharon por reducir la brecha creando condiciones propicias para la mejora económica de la comunidad afroamericana.

Nueva Orleans se volvió cada vez más dependiente del turismo como pilar económico durante las administraciones de Sidney Barthelemy (1986-1994) y Marc Morial (1994-2002). Los niveles relativamente bajos de logros educativos, las altas tasas de pobreza en los hogares y el aumento de la delincuencia amenazaron la prosperidad de la ciudad en las últimas décadas del siglo. [70] Los efectos negativos de estas condiciones socioeconómicas se alinearon mal con los cambios de finales del siglo XX en la economía de los Estados Unidos, que reflejaron un paradigma postindustrial basado en el conocimiento en el que las habilidades mentales y la educación eran más importantes para avance que las habilidades manuales.

Control de desagües e inundaciones

En el siglo XX, el gobierno y los líderes empresariales de Nueva Orleans creían que necesitaban drenar y desarrollar las áreas periféricas para facilitar la expansión de la ciudad. El desarrollo más ambicioso durante este período fue un plan de drenaje ideado por el ingeniero e inventor A. Baldwin Wood , diseñado para romper el dominio del pantano circundante sobre la expansión geográfica de la ciudad. Hasta entonces, el desarrollo urbano en Nueva Orleans se limitaba en gran medida a terrenos más altos a lo largo de los diques y pantanos naturales de los ríos .

El sistema de bombeo de Wood permitió a la ciudad drenar grandes extensiones de pantanos y marismas y expandirse a áreas bajas. Durante el siglo XX, el rápido hundimiento , tanto natural como inducido por el hombre, provocó que estas áreas recién pobladas se hundieran a varios pies por debajo del nivel del mar. [71] [72]

Nueva Orleans era vulnerable a las inundaciones incluso antes de que la huella de la ciudad se apartara del terreno elevado natural cerca del río Mississippi. Sin embargo, a finales del siglo XX, los científicos y los residentes de Nueva Orleans se dieron cuenta gradualmente de la creciente vulnerabilidad de la ciudad. En 1965, las inundaciones del huracán Betsy mataron a decenas de residentes, aunque la mayor parte de la ciudad permaneció seca. La inundación provocada por la lluvia del 8 de mayo de 1995 demostró la debilidad del sistema de bombeo. Después de ese evento, se tomaron medidas para mejorar drásticamente la capacidad de bombeo. En las décadas de 1980 y 1990, los científicos observaron que la erosión extensa, rápida y continua de las marismas y los pantanos que rodean a Nueva Orleans , especialmente la relacionada con laMississippi River – Gulf Outlet Canal , tuvo el resultado involuntario de dejar a la ciudad más vulnerable que antes a las catastróficas marejadas ciclónicas inducidas por huracanes .

Siglo 21

Huracan Katrina

Nueva Orleans se vio catastróficamente afectada por lo que Raymond B. Seed llamó "el peor desastre de ingeniería del mundo desde Chernobyl ", cuando el sistema federal de diques falló durante el huracán Katrina el 29 de agosto de 2005. [73] Cuando el huracán se acercó a la ciudad el 29 de agosto de 2005, la mayoría de los residentes habían sido evacuados. Cuando el huracán pasó por la región de la Costa del Golfo , el sistema federal de protección contra inundaciones de la ciudad falló, lo que resultó en el peor desastre de ingeniería civil en la historia de Estados Unidos. [74] Muros contra inundaciones y diques construidos por el Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército de los Estados Unidosfallaron por debajo de las especificaciones de diseño y el 80% de la ciudad se inundó. Decenas de miles de residentes que se habían quedado fueron rescatados o se dirigieron a refugios de último recurso en el Louisiana Superdome o el New Orleans Morial Convention Center . Se registró la muerte de más de 1.500 personas en Luisiana, la mayoría en Nueva Orleans, mientras que otras siguen desaparecidas. [75] [76] Antes del huracán Katrina, la ciudad pidió la primera evacuación obligatoria en su historia, seguida de otra evacuación obligatoria tres años después con el huracán Gustav .

Huracán rita

La ciudad fue declarada fuera de los límites de los residentes mientras comenzaban los esfuerzos para limpiar después del huracán Katrina . La aproximación del huracán Rita en septiembre de 2005 provocó que se pospusieran los esfuerzos de repoblación, [77] y el Lower Ninth Ward fue inundado por la marejada ciclónica de Rita. [76]

Recuperación posterior a un desastre

Debido a la magnitud del daño, muchas personas se reubicaron permanentemente fuera del área. Los esfuerzos federales, estatales y locales apoyaron la recuperación y reconstrucción en vecindarios severamente dañados. La Oficina del Censo en julio de 2006 estimó que la población era de 223.000 habitantes; un estudio posterior estimó que 32.000 residentes adicionales se habían trasladado a la ciudad en marzo de 2007, lo que eleva la población estimada a 255.000, aproximadamente el 56% del nivel de población anterior a Katrina. Otra estimación, basada en el uso de servicios públicos de julio de 2007, estimó que la población era aproximadamente 274.000 o el 60% de la población anterior a Katrina. Estas estimaciones son algo menores a una tercera estimación, según los registros de entrega de correo, del Centro de datos de la comunidad de Greater New Orleans en junio de 2007,lo que indicó que la ciudad había recuperado aproximadamente dos tercios de su población anterior a Katrina.[78] En 2008, la Oficina del Censo revisó su estimación de población para la ciudad hacia arriba, a 336,644. [79] Más recientemente, en julio de 2015, la población había vuelto a ser de 386.617, es decir, el 80% de lo que era en 2000. [80]

Han regresado varios eventos turísticos importantes y otras formas de ingresos para la ciudad. Regresaron las grandes convenciones. [81] [82] Los juegos de bolos universitarios regresaron para la temporada 2006-2007. Los New Orleans Saints regresaron esa temporada. Los New Orleans Hornets (ahora llamados Pelicans) regresaron a la ciudad para la temporada 2007-2008. Nueva Orleans fue sede del Juego de Estrellas de la NBA de 2008 . Además, la ciudad fue sede del Super Bowl XLVII .

Los principales eventos anuales como Mardi Gras , Voodoo Experience y el Jazz & Heritage Festival nunca fueron desplazados ni cancelados. En 2007 se creó un nuevo festival anual, "El encierro de Nueva Orleans". [83]

El 7 de febrero de 2017, un gran tornado en cuña EF3 golpeó partes del lado este de la ciudad, dañando casas y otros edificios, así como destruyendo un parque de casas móviles. Al menos 25 personas resultaron heridas por el evento. [84]

Geografía

Nueva Orleans está ubicada en el delta del río Mississippi , al sur del lago Pontchartrain , a orillas del río Mississippi , aproximadamente a 105 millas (169 km) río arriba del golfo de México . Según la Oficina del Censo de EE. UU. , El área de la ciudad es de 350 millas cuadradas (910 km 2 ), de las cuales 169 millas cuadradas (440 km 2 ) son tierra y 181 millas cuadradas (470 km 2 ) (52%) son agua. [85] El área a lo largo del río se caracteriza por crestas y hondonadas.

Elevación

Nueva Orleans se estableció originalmente en los diques naturales del río o en terrenos elevados. Después de la Ley de Control de Inundaciones de 1965 , el Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército de EE. UU. Construyó muros contra inundaciones y diques artificiales alrededor de una huella geográfica mucho más grande que incluía pantanos y marismas anteriores. Con el tiempo, el bombeo de agua de las marismas permitió el desarrollo en áreas de menor elevación. En la actualidad, la mitad de la ciudad está al nivel del mar medio local o por debajo de ella, mientras que la otra mitad está ligeramente por encima del nivel del mar. La evidencia sugiere que algunas partes de la ciudad pueden estar perdiendo altura debido al hundimiento . [86]

Un estudio de 2007 de la Universidad de Tulane y Xavier sugirió que "el 51% ... de las porciones urbanizadas contiguas de las parroquias de Orleans, Jefferson y St. Bernard se encuentran al nivel del mar o sobre él", con las áreas más densamente pobladas generalmente en terrenos más altos. La elevación promedio de la ciudad está actualmente entre 1 pie (0,30 m) y 2 pies (0,61 m) por debajo del nivel del mar, con algunas partes de la ciudad tan altas como 20 pies (6 m) en la base del dique del río en Uptown. y otros tan bajo como 7 pies (2 m) por debajo del nivel del mar en los confines más lejanos del este de Nueva Orleans . [87] [88] Sin embargo, un estudio publicado por la Revista de Ingeniería Hidrológica de la ASCE en 2016 declaró:

... la mayor parte de Nueva Orleans propiamente dicha, alrededor del 65%, se encuentra en el nivel medio del mar o por debajo de él, según lo definido por la elevación promedio del lago Pontchartrain [89]

La magnitud del hundimiento potencialmente causado por el drenaje de los pantanos naturales en el área de Nueva Orleans y el sureste de Louisiana es un tema de debate. Un estudio publicado en Geología en 2006 por un profesor asociado de la Universidad de Tulane afirma:

Si bien la erosión y la pérdida de humedales son grandes problemas a lo largo de la costa de Luisiana, el sótano de 30 pies (9,1 m) a 50 pies (15 m) debajo de gran parte del delta del Mississippi ha sido muy estable durante los últimos 8.000 años con tasas de hundimiento insignificantes. [90]

Sin embargo, el estudio señaló que los resultados no se aplicaban necesariamente al delta del río Mississippi ni al área metropolitana de Nueva Orleans propiamente dicha. Por otro lado, un informe de la Sociedad Estadounidense de Ingenieros Civiles afirma que "Nueva Orleans se está hundiendo (hundiéndose)": [91]

Grandes porciones de las parroquias de Orleans, St. Bernard y Jefferson se encuentran actualmente por debajo del nivel del mar y continúan hundiéndose. Nueva Orleans está construida sobre miles de pies de arena blanda, limo y arcilla. El hundimiento, o asentamiento de la superficie del suelo, ocurre naturalmente debido a la consolidación y oxidación de suelos orgánicos (llamados "pantanos" en Nueva Orleans) y al bombeo local de agua subterránea. En el pasado, las inundaciones y la deposición de sedimentos del río Mississippi contrarrestaron el hundimiento natural, dejando el sureste de Luisiana al nivel del mar o por encima de él . Sin embargo, debido a las principales estructuras de control de inundaciones que se están construyendo río arriba en el río Mississippi y a los diques que se están construyendo alrededor de Nueva Orleans, las capas frescas de sedimento no están reponiendo el suelo perdido por el hundimiento. [91]

En mayo de 2016, la NASA publicó un estudio que sugería que la mayoría de las áreas, de hecho, estaban experimentando hundimientos a una "tasa muy variable" que era "en general consistente, pero algo más alta que los estudios anteriores". [92]

Paisaje urbano

El Distrito Central de Negocios está ubicado inmediatamente al norte y al oeste del Mississippi y fue históricamente llamado el "Barrio Americano" o el "Sector Americano". Se desarrolló después del corazón del asentamiento francés y español. Incluye Lafayette Square . La mayoría de las calles de esta zona se abren en abanico desde un punto central. Las calles principales incluyen Canal Street , Poydras Street, Tulane Avenue y Loyola Avenue. Canal Street divide la zona tradicional del " centro " de la zona " alta ".

Cada calle que cruza Canal Street entre el río Mississippi y Rampart Street , que es el extremo norte del Barrio Francés, tiene un nombre diferente para las partes "uptown" y "downtown". Por ejemplo, St. Charles Avenue , conocida por su línea de tranvías, se llama Royal Street debajo de Canal Street, aunque donde atraviesa el Distrito Central de Negocios entre Canal y Lee Circle, se llama correctamente St. Charles Street. [93] En otras partes de la ciudad, Canal Street sirve como punto de división entre las porciones "Sur" y "Norte" de varias calles. En el lenguaje local, centro significa "río abajo de Canal Street", mientras que zona altasignifica "río arriba de Canal Street". Los vecindarios del centro incluyen French Quarter , Tremé , 7th Ward , Faubourg Marigny , Bywater (Upper Ninth Ward) y Lower Ninth Ward . Los vecindarios de Uptown incluyen Warehouse District, Lower Garden District , Garden District , Irish Channel , University District, Carrollton , Gert Town , Fontainebleau y Broadmoor . Sin embargo, el almacén y el distrito central de negocios se denominan con frecuencia "Centro" como una región específica, como en el Distrito de Desarrollo del Centro.

Otros distritos importantes dentro de la ciudad incluyen Bayou St. John , Mid-City , Gentilly , Lakeview , Lakefront, New Orleans East y Argel .

Arquitectura histórica y residencial

Nueva Orleans es mundialmente famosa por su abundancia de estilos arquitectónicos que reflejan la herencia multicultural de la ciudad. Aunque Nueva Orleans posee numerosas estructuras de importancia arquitectónica nacional, es igualmente, si no más, venerada por su enorme entorno histórico construido en gran parte intacto (incluso posterior a Katrina). Se han establecido veinte distritos históricos del Registro Nacional y catorce distritos históricos locales ayudan en la preservación. Trece de los distritos son administrados por la Comisión de Monumentos Históricos del Distrito Histórico de Nueva Orleans (HDLC), mientras que uno, el Barrio Francés, es administrado por la Comisión Vieux Carre (VCC). Además, tanto el Servicio de Parques Nacionales , a través del Registro Nacional de Lugares Históricos, y el HDLC han marcado edificios individuales, muchos de los cuales se encuentran fuera de los límites de los distritos históricos existentes. [94]

Los estilos de vivienda incluyen la casa de la escopeta y el estilo bungalow . Las casas adosadas y las cabañas criollas, que destacan por sus grandes patios y sus intrincados balcones de hierro, se alinean en las calles del Barrio Francés. Son notables las casas adosadas estadounidenses, las casas de doble galería y las cabañas de pasillo central elevadas. St. Charles Avenue es famosa por sus grandes casas anteriores a la guerra . Sus mansiones tienen varios estilos, como el renacimiento griego , el colonial americano y los estilos victorianos de la reina Ana y la arquitectura italiana . Nueva Orleans también se destaca por sus grandes cementerios católicos de estilo europeo.

Edificios mas altos

Durante gran parte de su historia, el horizonte de Nueva Orleans mostró solo estructuras de baja y media altura. Los suelos blandos son susceptibles de hundirse y existían dudas sobre la viabilidad de construir rascacielos. Los avances en ingeniería a lo largo del siglo XX finalmente hicieron posible construir cimientos sólidos en los cimientos que subyacen a las estructuras. En la década de 1960, el World Trade Center de Nueva Orleans y la Plaza Tower demostraron la viabilidad de los rascacielos. One Shell Square se convirtió en el edificio más alto de la ciudad en 1972. El boom petrolero de la década de 1970 y principios de la de 1980 redefinió el horizonte de Nueva Orleans con el desarrollo del corredor de Poydras Street. La mayoría están agrupadas a lo largo de Canal Street y Poydras Street en elDistrito central de negocios .

| Nombre | Cuentos | Altura |

|---|---|---|

| Un cuadrado de concha | 51 | 697 pies (212 m) |

| Place St. Charles | 53 | 645 pies (197 m) |

| Plaza Tower | 45 | 531 pies (162 m) |

| Centro de energía | 39 | 530 pies (160 m) |

| First Bank y Trust Tower | 36 | 481 pies (147 m) |

Clima

El clima de Nueva Orleans es subtropical húmedo ( Köppen : Cfa ), con inviernos cortos, generalmente suaves y veranos calurosos y húmedos; la mayoría de los suburbios y partes de los distritos 9 y 15 se encuentran en la Zona de Resistencia a las Plantas 9a del USDA , mientras que los otros 15 distritos de la ciudad tienen una calificación de 9b en total. [95] La temperatura promedio diaria mensual varía de 53,4 ° F (11,9 ° C) en enero a 83,3 ° F (28,5 ° C) en julio y agosto. Oficialmente, según lo medido en el Aeropuerto Internacional de Nueva Orleans, los registros de temperatura oscilan entre 11 y 102 ° F (-12 a 39 ° C) el 23 de diciembre de 1989 y el 22 de agosto de 1980, respectivamente; Audubon Park ha registrado temperaturas que oscilan entre 6 ° F (−14 ° C) el 13 de febrero de 1899hasta 104 ° F (40 ° C) el 24 de junio de 2009. [96] Los puntos de rocío en los meses de verano (junio-agosto) son relativamente altos, oscilando entre 71.1 y 73.4 ° F (21.7 a 23.0 ° C). [97]

La precipitación media es de 62,5 pulgadas (1,590 mm) al año; los meses de verano son los más húmedos, mientras que octubre es el mes más seco. [96] Las precipitaciones en invierno suelen acompañar al paso de un frente frío. En promedio, hay 77 días de 90 ° F (32 ° C) + máximos, 8.1 días por invierno donde el máximo no supera los 50 ° F (10 ° C) y 8.0 noches con bajas heladas anualmente. Es raro que la temperatura alcance los 20 o 100 ° F (−7 o 38 ° C), siendo la última aparición de cada uno el 5 de febrero de 1996 y el 26 de junio de 2016, respectivamente. [96]

Nueva Orleans experimenta nevadas solo en raras ocasiones. Una pequeña cantidad de nieve cayó durante la tormenta de nieve de la víspera de Navidad de 2004 y nuevamente en Navidad (25 de diciembre) cuando una combinación de lluvia, aguanieve y nieve cayó sobre la ciudad, dejando algunos puentes helados. La tormenta de nieve de la víspera de Año Nuevo de 1963 afectó a Nueva Orleans y trajo 11 cm (4,5 pulgadas). La nieve volvió a caer el 22 de diciembre de 1989 durante la ola de frío de los Estados Unidos de diciembre de 1989 , cuando la mayor parte de la ciudad recibió 1 a 2 pulgadas (2,5 a 5,1 cm).

La última nevada significativa en Nueva Orleans fue la mañana del 11 de diciembre de 2008. [98]

| Datos climáticos del Aeropuerto Internacional Louis Armstrong de Nueva Orleans (normales de 1981 a 2010, [a] extremos de 1946 al presente) [b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mes | ene | feb | mar | abr | Mayo | jun | jul | ago | sep | oct | nov | dic | Año |

| Registro alto ° F (° C) | 83 (28) | 85 (29) | 89 (32) | 92 (33) | 96 (36) | 101 (38) | 101 (38) | 102 (39) | 101 (38) | 95 (35) | 87 (31) | 84 (29) | 102 (39) |

| Máximo medio ° F (° C) | 77,2 (25,1) | 78,9 (26,1) | 82,3 (27,9) | 86,7 (30,4) | 91,5 (33,1) | 94,5 (34,7) | 96,0 (35,6) | 96,4 (35,8) | 93,5 (34,2) | 89,0 (31,7) | 83,7 (28,7) | 79,7 (26,5) | 97,3 (36,3) |

| Promedio alto ° F (° C) | 62,1 (16,7) | 65,4 (18,6) | 71,8 (22,1) | 78,2 (25,7) | 85,2 (29,6) | 89,5 (31,9) | 91,2 (32,9) | 91,2 (32,9) | 87,5 (30,8) | 80,0 (26,7) | 71,8 (22,1) | 64,4 (18,0) | 78,2 (25,7) |

| Promedio bajo ° F (° C) | 44,7 (7,1) | 48,0 (8,9) | 53,5 (11,9) | 60,0 (15,6) | 68,1 (20,1) | 73,5 (23,1) | 75,3 (24,1) | 75,3 (24,1) | 72,0 (22,2) | 62,6 (17,0) | 53,5 (11,9) | 46,9 (8,3) | 61,2 (16,2) |

| Mínimo medio ° F (° C) | 27,6 (−2,4) | 31,3 (−0,4) | 36,8 (2,7) | 44,6 (7,0) | 56,0 (13,3) | 65,7 (18,7) | 69,9 (21,1) | 70,0 (21,1) | 60,6 (15,9) | 45,6 (7,6) | 37,6 (3,1) | 29,6 (−1,3) | 24,6 (−4,1) |

| Grabar bajo ° F (° C) | 14 (−10) | 16 (−9) | 25 (−4) | 32 (0) | 41 (5) | 50 (10) | 60 (16) | 60 (16) | 42 (6) | 35 (2) | 24 (−4) | 11 (−12) | 11 (−12) |

| Precipitación promedio pulgadas (mm) | 5,15 (131) | 5,30 (135) | 4,55 (116) | 4,61 (117) | 4,63 (118) | 8.06 (205) | 5,93 (151) | 5,98 (152) | 4,97 (126) | 3,54 (90) | 4,49 (114) | 5,24 (133) | 62,45 (1.586) |

| Días de precipitación promedio (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.3 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 6,9 | 7.7 | 12,9 | 13,6 | 13,1 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 7,9 | 9.2 | 114,8 |

| Media de humedad relativa (%) | 75,6 | 73,0 | 72,9 | 73,4 | 74,4 | 76,4 | 79,2 | 79,4 | 77,8 | 74,9 | 77,2 | 76,9 | 75,9 |

| Promedio de horas de sol mensuales | 153,0 | 161,5 | 219,4 | 251,9 | 278,9 | 274,3 | 257,1 | 251,9 | 228,7 | 242,6 | 171,8 | 157,8 | 2.648,9 |

| Porcentaje posible de luz solar | 47 | 52 | 59 | sesenta y cinco | 66 | sesenta y cinco | 60 | 62 | 62 | 68 | 54 | 50 | 60 |

| Fuente: NOAA (humedad relativa y sol 1961-1990) [c] [96] [100] [97] | |||||||||||||

| Datos climáticos de Audubon Park, Nueva Orleans (extremos desde 1893 hasta el presente) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mes | ene | feb | mar | abr | Mayo | jun | jul | ago | sep | oct | nov | dic | Año |

| Registro alto ° F (° C) | 84 (29) | 85 (29) | 91 (33) | 93 (34) | 99 (37) | 104 (40) | 102 (39) | 103 (39) | 101 (38) | 97 (36) | 92 (33) | 85 (29) | 104 (40) |

| Grabar bajo ° F (° C) | 13 (−11) | 6 (−14) | 26 (−3) | 32 (0) | 46 (8) | 54 (12) | 61 (16) | 60 (16) | 49 (9) | 35 (2) | 26 (−3) | 12 (−11) | 6 (−14) |

| Fuente: NOAA [96] | |||||||||||||

Amenaza de ciclones tropicales

Los huracanes representan una grave amenaza para el área, y la ciudad está particularmente en riesgo debido a su baja elevación, porque está rodeada de agua del norte, este y sur y debido a la costa hundida de Luisiana. [101] Según la Agencia Federal para el Manejo de Emergencias , Nueva Orleans es la ciudad más vulnerable del país a los huracanes. [102] De hecho, partes del Gran Nueva Orleans han sido inundadas por el huracán Grand Isle de 1909 , [103] el huracán de Nueva Orleans de 1915 , [103] el huracán Fort Lauderdale de 1947 , [103] el huracán Flossy [104] en 1956,El huracán Betsy en 1965, el huracán Georges en 1998, los huracanes Katrina y Rita en 2005, el huracán Gustav en 2008 y el huracán Zeta en 2020 (Zeta también fue el huracán más intenso que pasó sobre Nueva Orleans) con las inundaciones en Betsy siendo significativas y en algunos barrios severo, y el de Katrina es desastroso en la mayor parte de la ciudad. [105] [106] [107]

El 29 de agosto de 2005, la marejada ciclónica del huracán Katrina causó fallas catastróficas de los diques diseñados y construidos por el gobierno federal , inundando el 80% de la ciudad. [108] [109] Un informe de la Sociedad Estadounidense de Ingenieros Civiles dice que "si los diques y los muros de inundación no hubieran fallado y las estaciones de bombeo hubieran funcionado, casi dos tercios de las muertes no habrían ocurrido". [91]

Nueva Orleans siempre ha tenido que considerar el riesgo de huracanes, pero los riesgos son dramáticamente mayores hoy debido a la erosión costera por la interferencia humana. [110] Desde principios del siglo XX, se ha estimado que Luisiana ha perdido 2000 millas cuadradas (5000 km 2 ) de costa (incluidas muchas de sus islas de barrera), que alguna vez protegieron a Nueva Orleans contra las marejadas ciclónicas. Después del huracán Katrina, el Cuerpo de Ingenieros del Ejército ha instituido medidas masivas de reparación de diques y protección contra huracanes para proteger la ciudad.

En 2006, los votantes de Louisiana adoptaron por abrumadora mayoría una enmienda a la constitución del estado para dedicar todos los ingresos de la perforación en alta mar a restaurar la erosionada línea costera de Louisiana. [111] El Congreso ha asignado $ 7 mil millones para reforzar la protección contra inundaciones de Nueva Orleans. [112]

Según un estudio de la Academia Nacional de Ingeniería y el Consejo Nacional de Investigación , los diques y muros de inundación que rodean a Nueva Orleans, sin importar cuán grandes o resistentes sean, no pueden brindar una protección absoluta contra desbordes o fallas en eventos extremos. Los diques y los muros contra inundaciones deben verse como una forma de reducir los riesgos de huracanes y marejadas ciclónicas, no como medidas que eliminen por completo el riesgo. Para las estructuras en áreas peligrosas y los residentes que no se reubican, el comité recomendó importantes medidas de protección contra inundaciones , como elevar el primer piso de los edificios al menos al nivel de inundación de 100 años. [113]

Demografía

| Año | Música pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1769 | 3,190 | - |

| 1778 | 3,060 | −4,1% |

| 1791 | 5.497 | + 79,6% |

| 1810 | 17.242 | + 213,7% |

| 1820 | 27,176 | + 57,6% |

| 1830 | 46.082 | + 69,6% |

| 1840 | 102,193 | + 121,8% |

| 1850 | 116,375 | + 13,9% |

| 1860 | 168.675 | + 44,9% |

| 1870 | 191,418 | + 13,5% |

| 1880 | 216,090 | + 12,9% |

| 1890 | 242,039 | + 12,0% |

| 1900 | 287,104 | + 18,6% |

| 1910 | 339,075 | + 18,1% |

| 1920 | 387,219 | + 14,2% |

| 1930 | 458,762 | + 18,5% |

| 1940 | 494,537 | + 7,8% |

| 1950 | 570,445 | + 15,3% |

| 1960 | 627,525 | + 10,0% |

| 1970 | 593,471 | −5,4% |

| 1980 | 557,515 | −6,1% |

| 1990 | 496,938 | −10,9% |

| 2000 | 484,674 | −2,5% |

| 2010 | 343,829 | −29,1% |

| 2019 | 390.144 | + 13,5% |

| Población dada para la ciudad de Nueva Orleans, no para la parroquia de Orleans, antes de que Nueva Orleans absorbiera los suburbios y áreas rurales de la parroquia de Orleans en 1874, desde entonces la ciudad y la parroquia han sido colindantes. La población de la parroquia de Orleans era 41.351 en 1820; 49.826 en 1830; 102.193 en 1840; 119.460 en 1850; 174.491 en 1860; y 191418 en 1870. Fuente: Censo decenal de EE. UU. [114] Cifras históricas de población [79] [115] [116] [117] [118] 1790-1960 [119] 1900-1990 [120] 1990-2000 [121] 2010 –2013 [122] Estimación de 2019 [3] | ||

Según el censo estadounidense de 2010 , 343,829 personas y 189,896 hogares vivían en Nueva Orleans. [123] En 2019, la Oficina del Censo de EE. UU. Estimó que Nueva Orleans tenía 390.144 residentes. [6]

A partir de 1960, la población disminuyó debido a factores como los ciclos de producción de petróleo y turismo, [124] [125] ya medida que aumentó la suburbanización (como en muchas ciudades), [126] y los trabajos migraron a las parroquias circundantes. [127] Esta disminución económica y demográfica resultó en altos niveles de pobreza en la ciudad; en 1960 tenía la quinta tasa de pobreza más alta de todas las ciudades de EE. UU. [128] y era casi el doble del promedio nacional en 2005, con un 24,5%. [126] Nueva Orleans experimentó un aumento en la segregación residencial de 1900 a 1980, dejando a los pobres afroamericanos desproporcionadamente en lugares más viejos y bajos. [127]Estas áreas fueron especialmente susceptibles a daños por inundaciones y tormentas. [129]

La última estimación de población antes del huracán Katrina era de 454.865, al 1 de julio de 2005. [130] Un análisis de población publicado en agosto de 2007 estimó que la población era de 273.000, el 60% de la población anterior a Katrina y un aumento de aproximadamente 50.000 desde julio. 2006. [131] Un informe de septiembre de 2007 del Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, que rastrea la población según las cifras del Servicio Postal de EE. UU., Encontró que en agosto de 2007, poco más de 137,000 hogares recibieron correo. Eso se compara con unos 198.000 hogares en julio de 2005, lo que representa alrededor del 70% de la población anterior a Katrina. [132] Más recientemente, la Oficina del Censo revisó al alza su estimación de población de 2008 para la ciudad, a 336,644 habitantes. [79]En 2010, las estimaciones mostraron que los vecindarios que no se inundaron estaban cerca o incluso más del 100% de sus poblaciones anteriores a Katrina. [133]

Katrina desplazó a 800.000 personas, lo que contribuyó significativamente a la disminución. [134] Los afroamericanos, los inquilinos, los ancianos y las personas con bajos ingresos se vieron afectados de manera desproporcionada por Katrina, en comparación con los residentes ricos y blancos. [135] [136] A raíz de Katrina, el gobierno de la ciudad encargó a grupos como la Comisión Bring New Orleans Back , el Plan de reconstrucción del vecindario de Nueva Orleans, el Plan Unificado de Nueva Orleans y la Oficina de Gestión de la Recuperación para contribuir a los planes que abordan la despoblación. Sus ideas incluyen la reducción de la ciudad de la huella de antes de la tormenta, la incorporación de voces de la comunidad en los planes de desarrollo, y la creación de espacios verdes , [135]algunos de los cuales incitaron a la controversia. [137] [138]

Un estudio de 2006 realizado por investigadores de la Universidad de Tulane y la Universidad de California, Berkeley, determinó que entre 10.000 y 14.000 inmigrantes indocumentados , muchos de ellos de México , residían en Nueva Orleans. [139] El Departamento de Policía de Nueva Orleans inició una nueva política para "dejar de cooperar con las autoridades federales de inmigración" a partir del 28 de febrero de 2016. [140] Janet Murguía , presidenta y directora ejecutiva del Consejo Nacional de La Raza , declaró que hasta 120.000 trabajadores hispanos vivían en Nueva Orleans. En junio de 2007, un estudio indicó que la población hispana había aumentado de 15.000, antes de Katrina, a más de 50.000.[141] De 2010 a 2014, la ciudad creció un 12%, agregando un promedio de más de 10,000 nuevos residentes cada año después del censo de 2010 de EE . UU . [115]

En 2010 [update], el 90,3% de los residentes de 5 años o más hablaban inglés en casa como idioma principal , mientras que el 4,8% hablaba español, el 1,9% vietnamita y el 1,1% hablaba francés. En total, el 9,7% de la población de 5 años o más hablaba una lengua materna que no era el inglés. [142]

Raza y etnia

| Composición racial | 2010 [143] | 1990 [144] | 1970 [144] | 1940 [144] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blanco | 33,0% | 34,9% | 54,5% | 69.7% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 30.5% | 33.1% | 50.6%[145] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 60.2% | 61.9% | 45.0% | 30.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 5.2% | 3.5% | 4.4%[145] | n/a |

| Asian | 2.9% | 1.9% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

The racial and ethnic makeup of New Orleans was 60.2% African American, 33.0% White, 2.9% Asian (1.7% Vietnamese, 0.3% Indian, 0.3% Chinese, 0.1% Filipino, 0.1% Korean), 0.0% Pacific Islander, and 1.7% were people of two or more races in 2010.[123] People of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 5.3% of the population; 1.3% were Mexican, 1.3% Honduran, 0.4% Cuban, 0.3% Puerto Rican, and 0.3% Nicaraguan. In 2018, the racial and ethnic makeup of the city was 30.6% non-Hispanic white, 59% Black or African American, 0.1% American Indian or Alaska Native, 2.9% Asian, <0.0% Pacific Islander, 0.4% from some other race, and 1.5% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race made up 5.5% of the population in 2018.[146]

As of 2011[update] the Hispanic and Latin American population had grown in the New Orleans area, including in Kenner, central Metairie, and Terrytown in Jefferson Parish and eastern New Orleans and Mid-City in New Orleans proper.[147] Among the Asian American community, the earliest Filipino Americans to live within the city arrived in the early 1800s.[148]

After Katrina the small Brazilian American population expanded. Portuguese speakers were the second most numerous group to take English as a second language classes in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans, after Spanish speakers. Many Brazilians worked in skilled trades such as tile and flooring, although fewer worked as day laborers than did Latinos. Many had moved from Brazilian communities in the northeastern United States, particularly Florida and Georgia. Brazilians settled throughout the metropolitan area. Most were undocumented. In January 2008 the New Orleans Brazilian population had a mid-range estimate of 3,000. By 2008 Brazilians had opened many small churches, shops and restaurants catering to their community.[149]

Religion

New Orleans' colonial history of French and Spanish settlement generated a strong Roman Catholic tradition. Catholic missions ministered to slaves and free people of color and established schools for them. In addition, many late 19th and early 20th century European immigrants, such as the Irish, some Germans, and Italians were Catholic. Within the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans (which includes not only the city but the surrounding parishes as well), 40% percent of the population is Roman Catholic.[150] Catholicism is reflected in French and Spanish cultural traditions, including its many parochial schools, street names, architecture and festivals, including Mardi Gras.

Influenced by the Bible Belt's prominent Protestant population, New Orleans also has a sizable non-Catholic Christian demographic. Roughly 12.2% of the population are Baptist, followed by 5.1% from another Christian faith including Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Oriental Orthodoxy, 3.1% Methodism, 1.8% Episcopalianism, 0.9% Presbyterianism, 0.8% Lutheranism, 0.8% from the Latter-Day Saints, and 0.6% Pentecostalism.[151] Of the Baptist population, the majority form the National Baptist Convention (USA and America), and the Southern Baptist Convention.[152]

New Orleans displays a distinctive variety of Louisiana Voodoo, due in part to syncretism with African and Afro-Caribbean Roman Catholic beliefs. The fame of voodoo practitioner Marie Laveau contributed to this, as did New Orleans' Caribbean cultural influences.[153][154][155] Although the tourism industry strongly associated Voodoo with the city, only a small number of people are serious adherents.

New Orleans was also home to the occultist Mary Oneida Toups, who was nicknamed the "Witch Queen of New Orleans". Toups' coven, The Religious Order of Witchcraft, was the first coven to be officially recognized as a religious institution by the state of Louisiana.[156]

Jewish settlers, primarily Sephardim, settled in New Orleans from the early nineteenth century. Some migrated from the communities established in the colonial years in Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. The merchant Abraham Cohen Labatt helped found the first Jewish congregation in New Orleans in the 1830s, which became known as the Portuguese Jewish Nefutzot Yehudah congregation (he and some other members were Sephardic Jews, whose ancestors had lived in Portugal and Spain). Ashkenazi Jews from eastern Europe immigrated in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

By the 21st century, 10,000 Jews lived in New Orleans. This number dropped to 7,000 after Hurricane Katrina, but rose again after efforts to incentivize the community's growth resulted in the arrival of about an additional 2,000 Jews.[157] New Orleans synagogues lost members, but most re-opened in their original locations. The exception was Congregation Beth Israel, the oldest and most prominent Orthodox synagogue in the New Orleans region. Beth Israel's building in Lakeview was destroyed by flooding. After seven years of holding services in temporary quarters, the congregation consecrated a new synagogue on land purchased from the Reform Congregation Gates of Prayer in Metairie.[158]

A visible religious minority,[159][160] Muslims constitute 0.6% of the religious population as of 2019.[151] The Islamic demographic in New Orleans and its metropolitan area are mainly made up of Middle Eastern immigrants and African Americans.

Economy

New Orleans operates one of the world's largest and busiest ports and metropolitan New Orleans is a center of maritime industry.[161] The region accounts for a significant portion of the nation's oil refining and petrochemical production, and serves as a white-collar corporate base for onshore and offshore petroleum and natural gas production.

New Orleans is also a center for higher learning, with over 50,000 students enrolled in the region's eleven two- and four-year degree-granting institutions. Tulane University, a top-50 research university, is located in Uptown. Metropolitan New Orleans is a major regional hub for the health care industry and boasts a small, globally competitive manufacturing sector. The center city possesses a rapidly growing, entrepreneurial creative industries sector and is renowned for its cultural tourism. Greater New Orleans, Inc. (GNO, Inc.)[162] acts as the first point-of-contact for regional economic development, coordinating between Louisiana's Department of Economic Development and the various business development agencies.

Port

New Orleans began as a strategically located trading entrepôt and it remains, above all, a crucial transportation hub and distribution center for waterborne commerce. The Port of New Orleans is the fifth-largest in the United States based on cargo volume, and second-largest in the state after the Port of South Louisiana. It is the twelfth-largest in the U.S. based on cargo value. The Port of South Louisiana, also located in the New Orleans area, is the world's busiest in terms of bulk tonnage. When combined with Port of New Orleans, it forms the 4th-largest port system in volume. Many shipbuilding, shipping, logistics, freight forwarding and commodity brokerage firms either are based in metropolitan New Orleans or maintain a local presence. Examples include Intermarine, Bisso Towboat, Northrop Grumman Ship Systems, Trinity Yachts, Expeditors International, Bollinger Shipyards, IMTT, International Coffee Corp, Boasso America, Transoceanic Shipping, Transportation Consultants Inc., Dupuy Storage & Forwarding and Silocaf. The largest coffee-roasting plant in the world, operated by Folgers, is located in New Orleans East.

New Orleans is located near to the Gulf of Mexico and its many oil rigs. Louisiana ranks fifth among states in oil production and eighth in reserves. It has two of the four Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) storage facilities: West Hackberry in Cameron Parish and Bayou Choctaw in Iberville Parish. The area hosts 17 petroleum refineries, with a combined crude oil distillation capacity of nearly 2.8 million barrels per day (450,000 m3/d), the second highest after Texas. Louisiana's numerous ports include the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), which is capable of receiving the largest oil tankers. Given the quantity of oil imports, Louisiana is home to many major pipelines: Crude Oil (Exxon, Chevron, BP, Texaco, Shell, Scurloch-Permian, Mid-Valley, Calumet, Conoco, Koch Industries, Unocal, U.S. Dept. of Energy, Locap); Product (TEPPCO Partners, Colonial, Plantation, Explorer, Texaco, Collins); and Liquefied Petroleum Gas (Dixie, TEPPCO, Black Lake, Koch, Chevron, Dynegy, Kinder Morgan Energy Partners, Dow Chemical Company, Bridgeline, FMP, Tejas, Texaco, UTP).[163] Several energy companies have regional headquarters in the area, including Royal Dutch Shell, Eni and Chevron. Other energy producers and oilfield services companies are headquartered in the city or region, and the sector supports a large professional services base of specialized engineering and design firms, as well as a term office for the federal government's Minerals Management Service.

Business

The city is the home to a single Fortune 500 company: Entergy, a power generation utility and nuclear power plant operations specialist. After Katrina, the city lost its other Fortune 500 company, Freeport-McMoRan, when it merged its copper and gold exploration unit with an Arizona company and relocated that division to Phoenix. Its McMoRan Exploration affiliate remains headquartered in New Orleans.

Companies with significant operations or headquarters in New Orleans include: Pan American Life Insurance, Pool Corp, Rolls-Royce, Newpark Resources, AT&T, TurboSquid, iSeatz, IBM, Navtech, Superior Energy Services, Textron Marine & Land Systems, McDermott International, Pellerin Milnor, Lockheed Martin, Imperial Trading, Laitram, Harrah's Entertainment, Stewart Enterprises, Edison Chouest Offshore, Zatarain's, Waldemar S. Nelson & Co., Whitney National Bank, Capital One, Tidewater Marine, Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits, Parsons Brinckerhoff, MWH Global, CH2M Hill, Energy Partners Ltd, The Receivables Exchange, GE Capital, and Smoothie King.

Tourist and convention business

Tourism is a staple of the city's economy. Perhaps more visible than any other sector, New Orleans' tourist and convention industry is a $5.5 billion industry that accounts for 40 percent of city tax revenues. In 2004, the hospitality industry employed 85,000 people, making it the city's top economic sector as measured by employment.[164] New Orleans also hosts the World Cultural Economic Forum (WCEF). The forum, held annually at the New Orleans Morial Convention Center, is directed toward promoting cultural and economic development opportunities through the strategic convening of cultural ambassadors and leaders from around the world. The first WCEF took place in October 2008.[165]

Federal and military agencies

Federal agencies and the Armed forces operate significant facilities there. The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals operates at the US. Courthouse downtown. NASA's Michoud Assembly Facility is located in New Orleans East and has multiple tenants including Lockheed Martin and Boeing. It is a huge manufacturing complex that produced the external fuel tanks for the Space Shuttles, the Saturn V first stage, the Integrated Truss Structure of the International Space Station, and is now used for the construction of NASA's Space Launch System. The rocket factory lies within the enormous New Orleans Regional Business Park, also home to the National Finance Center, operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Crescent Crown distribution center. Other large governmental installations include the U.S. Navy's Space and Naval Warfare (SPAWAR) Systems Command, located within the University of New Orleans Research and Technology Park in Gentilly, Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base New Orleans; and the headquarters for the Marine Force Reserves in Federal City in Algiers.

Culture and contemporary life

Tourism

New Orleans has many visitor attractions, from the world-renowned French Quarter to St. Charles Avenue, (home of Tulane and Loyola Universities, the historic Pontchartrain Hotel and many 19th-century mansions) to Magazine Street with its boutique stores and antique shops.

According to current travel guides, New Orleans is one of the top ten most-visited cities in the United States; 10.1 million visitors came to New Orleans in 2004.[164][166] Prior to Katrina, 265 hotels with 38,338 rooms operated in the Greater New Orleans Area. In May 2007, that had declined to some 140 hotels and motels with over 31,000 rooms.[167]

A 2009 Travel + Leisure poll of "America's Favorite Cities" ranked New Orleans first in ten categories, the most first-place rankings of the 30 cities included. According to the poll, New Orleans was the best U.S. city as a spring break destination and for "wild weekends", stylish boutique hotels, cocktail hours, singles/bar scenes, live music/concerts and bands, antique and vintage shops, cafés/coffee bars, neighborhood restaurants, and people watching. The city ranked second for: friendliness (behind Charleston, South Carolina), gay-friendliness (behind San Francisco), bed and breakfast hotels/inns, and ethnic food. However, the city placed near the bottom in cleanliness, safety and as a family destination.[168][169]

The French Quarter (known locally as "the Quarter" or Vieux Carré), which was the colonial-era city and is bounded by the Mississippi River, Rampart Street, Canal Street, and Esplanade Avenue, contains popular hotels, bars and nightclubs. Notable tourist attractions in the Quarter include Bourbon Street, Jackson Square, St. Louis Cathedral, the French Market (including Café du Monde, famous for café au lait and beignets) and Preservation Hall. Also in the French Quarter is the old New Orleans Mint, a former branch of the United States Mint which now operates as a museum, and The Historic New Orleans Collection, a museum and research center housing art and artifacts relating to the history and the Gulf South.

Close to the Quarter is the Tremé community, which contains the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park and the New Orleans African American Museum—a site which is listed on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.

The Natchez is an authentic steamboat with a calliope that cruises the length of the city twice daily. Unlike most other places in the United States, New Orleans has become widely known for its elegant decay. The city's historic cemeteries and their distinct above-ground tombs are attractions in themselves, the oldest and most famous of which, Saint Louis Cemetery, greatly resembles Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.