Un árbol de levas ( OHC ) motor es un motor de pistón en el que el árbol de levas se encuentra en la cabeza del cilindro por encima de la cámara de combustión . [1] [2] Esto contrasta con los motores de válvulas en cabeza (OHV) anteriores, donde el árbol de levas está ubicado debajo de la cámara de combustión en el bloque del motor . [3]

Los motores de árbol de levas en cabeza simple (SOHC) tienen un árbol de levas por banco de cilindros . Los motores de doble árbol de levas en cabeza (DOHC, también conocido como "twin-cam". [4] ) tienen dos árboles de levas por banco. El primer automóvil de producción que usó un motor DOHC se construyó en 1910. El uso de motores DOHC aumentó lentamente desde la década de 1940, lo que llevó a la mayoría de los automóviles a principios de la década de 2000 a utilizar motores DOHC. [ cita requerida ]

Diseño [ editar ]

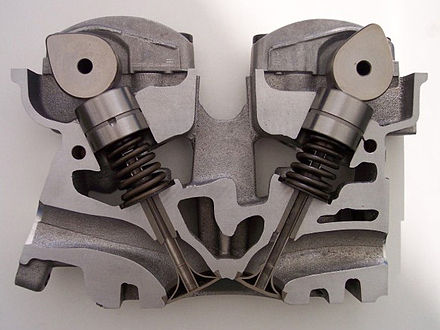

En un motor de árbol de levas en cabeza, el árbol de levas está ubicado en la parte superior del motor, por encima de la cámara de combustión . Esto contrasta el motor de válvulas en cabeza (OHV) anterior y las configuraciones del motor de cabeza plana , donde el árbol de levas está ubicado hacia abajo en el bloque del motor . Las válvulas de los motores OHC y OHV están ubicadas sobre la cámara de combustión; sin embargo, un motor OHV requiere varillas de empuje y balancines para transferir el movimiento del árbol de levas a las válvulas, mientras que un motor OHC tiene las válvulas accionadas directamente por el árbol de levas.

En comparación con los motores OHV con el mismo número de válvulas, hay menos componentes alternativos en un motor OHC y hay menos inercia del tren de válvulas en un motor OHC, lo que reduce la flotación de la válvula a velocidades del motor más altas (RPM). [1] Una desventaja es que el sistema utilizado para impulsar el árbol de levas (generalmente una cadena de distribución en los motores modernos) es más complejo en un motor OHC.

La otra ventaja principal de los motores OHC es que hay una mayor flexibilidad para optimizar el tamaño, la ubicación y la forma de los puertos de admisión y escape, ya que no hay varillas de empuje que deban evitarse. [1] Esto mejora el flujo de gas a través del motor, aumentando la potencia y la eficiencia del combustible.

Durante las reparaciones del motor que requieren la extracción de la culata de cilindros, una desventaja de los motores OHC es que la sincronización del árbol de levas debe restablecerse si se retira la culata de cilindros. En los automóviles Morris y Wolseley de 1920-1940 con motores OHC, las fugas de aceite en los sistemas de lubricación también fueron un problema. [5] ( págs . 15-18 )

Árbol de levas en cabeza simple (SOHC) [ editar ]

La configuración más antigua de motor de árbol de levas en cabeza es el diseño de árbol de levas simple o árbol de levas simple . [1] [6] Un motor SOHC tiene un árbol de levas por banco de cilindros, por lo tanto, un motor recto tiene un total de un árbol de levas. Un motor V o plano con un total de dos árboles de levas (uno por banco de cilindros) es un motor de árbol de levas en cabeza simple, no un motor de árbol de levas en cabeza doble.

Independientemente del número, el árbol de levas generalmente opera las válvulas indirectamente a través de un balancín . [1] [6]

La mayoría de los motores SOHC tienen dos válvulas por cilindro. Sin embargo, algunos motores, como el motor Triumph Dolomite Sprint de 1973 y el motor V6 de la serie J de Honda, tenían una configuración SOHC con cuatro válvulas por cilindro. Esto se logró mediante la ubicación del árbol de levas en el centro de la culata de cilindros, con balancines de igual longitud que accionaban las válvulas de admisión y escape. [7] Esta disposición se utilizó para proporcionar cuatro válvulas por cilindro mientras se minimiza la masa del tren de válvulas y se minimiza el tamaño total del motor. [8] [9] [10]

Doble árbol de levas en cabeza (DOHC) [ editar ]

Un doble árbol de levas , doble árbol de levas , o de doble leva motor tiene dos árboles de levas por banco de la cabeza del cilindro, [1] [2] [6] uno para las válvulas de admisión y el otro para las válvulas de escape. Por lo tanto, hay dos árboles de levas para un motor recto y un total de cuatro árboles de levas para un motor en V o un motor plano. A veces, un motor DOHC V se comercializa como quad cammotor, sin embargo, los dos árboles de levas "adicionales" son el resultado del diseño del motor en lugar de proporcionar un beneficio en comparación con otros motores DOHC. Para confundir aún más la terminología, algunos motores de motocicleta SOHC de dos cilindros en V y dos cilindros en V fabricados por Harley-Davidson, Indian, Riley Motors y Triumph se han comercializado con el término engañoso "motor de dos levas".

La mayoría de los motores DOHC tienen cuatro válvulas por cilindro, sin embargo, los motores DOHC con dos válvulas por cilindro incluyen el motor Alfa Romeo Twin Cam , el motor Jaguar XK6 , el primer motor Ford I4 DOHC y el motor Lotus Ford Twin Cam . [6]

El árbol de levas generalmente opera las válvulas directamente a través de un taqué de cubo . Un diseño DOHC permite un ángulo más amplio entre las válvulas de admisión y escape que en los motores SOHC, lo que mejora el flujo de gas a través del motor. Un beneficio adicional es que la bujía se puede colocar en la ubicación óptima, lo que a su vez mejora la eficiencia de la combustión. [6] [ enlace muerto ]

Componentes [ editar ]

Correa de distribución / cadena de distribución [ editar ]

La rotación de los árboles de levas es impulsada por el cigüeñal . Muchos motores del siglo XXI utilizan una correa de distribución dentada hecha de caucho y kevlar para impulsar el árbol de levas. [1] [6] [11] Las correas de distribución son económicas, producen un ruido mínimo y no necesitan lubricación. [12] ( p93 ) Una desventaja de las correas de distribución es la necesidad de un reemplazo regular de la correa; [12] ( p94 ) La vida útil recomendada de la banda normalmente varía entre aproximadamente 50 000 y 100 000 km (31 000 a 62 000 mi). [12] ( págs . 94-95 ) [13] ( pág . 250 )Si la correa de distribución no se reemplaza a tiempo y falla y el motor es un motor de interferencia , es de esperar que se produzcan daños importantes en el motor.

La primera aplicación automotriz conocida de correas de distribución para impulsar árboles de levas en cabeza fueron las especiales de carreras Devin-Panhard de 1953 construidas para la serie de carreras SCCA modificada en H en los Estados Unidos. [14] ( p62 ) Estos motores se basaron en motores Panhard OHV de dos cilindros planos, que se convirtieron en motores SOHC utilizando componentes de motores de motocicleta Norton. [14] ( p62 ) El primer automóvil de producción en usar una correa de distribución fue el coupé compacto Glas 1004 de 1962 . [15]

Otro método de transmisión del árbol de levas comúnmente utilizado en los motores modernos es una cadena de distribución , construida a partir de una o dos filas de cadenas de rodillos de metal . [1] [6] [11] A principios de la década de 1960, la mayoría de los diseños de árboles de levas en cabeza de los automóviles de producción utilizaban cadenas para impulsar el (los) árbol (s) de levas. [5] ( p17 ) Las cadenas de distribución generalmente no requieren reemplazo a intervalos regulares, sin embargo, la desventaja es que son más ruidosas que las correas de distribución. [13] ( p253 )

Tren de engranajes [ editar ]

A gear train system between the crankshaft and the camshaft is commonly used in diesel overhead camshaft engines used in heavy trucks.[16] Gear trains are less commonly used in OHC engines for light trucks or automobiles.[1]

Other camshaft drive systems[edit]

Several OHC engines up until the 1950s used a shaft with bevel gears to drive the camshaft. Examples include the 1908-1911 Maudslay 25/30,[17][18] the Bentley 3 Litre,[19] the 1929-1932 MG Midget, the 1925-1948 Velocette K series,[20] the 1931-1957 Norton International and the 1947-1962 Norton Manx.[21] In more recent times, the 1950-1974 Ducati Single,[22] 1973-1980 Ducati L-twin engine, 1999-2007 Kawasaki W650 and 2011-2016 Kawasaki W800 motorcycle engines have used bevel shafts.[23][24] The Crosley four cylinder was the last automotive engine to use the shaft tower design to drive the camshaft, from 1946 to 1952; the rights to the Crosley engine format were bought by a few different companies, including General Tire in 1952, followed by Fageol in 1955, Crofton in 1959, Homelite in 1961, and Fisher Pierce in 1966, after Crosley closed the automotive factory doors, and they continued to produce the same engine for several more years.

A camshaft drive using three sets of cranks and rods in parallel was used in the 1920-1923 Leyland Eight luxury car built in the United Kingdom.[25][26][27] A similar system was used in the 1926-1930 Bentley Speed Six and the 1930-1932 Bentley 8 Litre.[27][28] A two-rod system with counterweights at both ends was used by many models of the 1958-1973 NSU Prinz.[5](p16-18)

History[edit]

1900-1914[edit]

Among the first overhead camshaft engines were the 1902 Maudslay SOHC engine built in the United Kingdom[18](p210)[5](p906)[29] and the 1903 Marr Auto Car SOHC engine built in the United States.[30][31] The first DOHC engine was a Peugeot inline-four racing engine which powered the car that won the 1912 French Grand Prix. Another Peugeot with a DOHC engine won the 1913 French Grand Prix, followed by the Mercedes-Benz 18/100 GP with an SOHC engine winning the 1914 French Grand Prix.

The Isotta Fraschini Tipo KM— built in Italy from 1910-1914— was one of the first production cars to use an SOHC engine.[32]

World War I[edit]

During World War I, both the Allied and Central Powers; specifically those of the German Empire's Luftstreitkräfte air forces, sought to quickly apply the overhead camshaft technology of motor racing engines to military aircraft engines. The SOHC engine from the Mercedes 18/100 GP car (which won the 1914 French Grand Prix) became the starting point for both Mercedes' and Rolls Royce's aircraft engines. Mercedes created a series of six-cylinder engines which culminated in the Mercedes D.III. Rolls Royce reversed-engineered the Mercedes cylinder head design based on a racing car left in England at the beginning of the war, leading to the Rolls-Royce Eagle V12 engine. Other SOHC designs included the Spanish Hispano-Suiza 8 V8 engine (with a fully enclosed-drivetrain), the American Liberty L-12 V12 engine, which closely followed the later Mercedes D.IIIa design's partly-exposed SOHC valvetrain design; and the Max Friz-designed; German BMW IIIa straight-six engine. The DOHC Napier Lion W12 engine was built in Great Britain beginning in 1918.

Most of these engines used a shaft to transfer drive from the crankshaft up to the camshaft at the top of the engine. Large aircraft engines— particularly air-cooled engines— experienced considerable thermal expansion, causing the height of the cylinder block to vary during operating conditions. This expansion caused difficulties for pushrod engines, so an overhead camshaft engine using a shaft drive with sliding spline was the easiest way to allow for this expansion. These bevel shafts were usually in an external tube outside the block, and were known as "tower shafts".[33]

1914-1918 Hispano-Suiza 8A SOHC aircraft engine

1914-1918 Hispano-Suiza 8Be SOHC aircraft engine with "tower shafts" at the rear of each cylinder bank

1919-1944[edit]

An early American overhead camshaft production engine was the SOHC straight-eight engine used in the 1921-1926 Duesenberg Model A luxury car.[34]

In 1926, the Sunbeam 3 litre Super Sports became the first production car to use a DOHC engine.[35][36]

In the United States, Duesenberg added DOHC engines (alongside their existing SOHC engines) with the 1928 release of the Duesenberg Model J, which was powered by a DOHC straight-eight engine. The 1931-1935 Stutz DV32 was another early American luxury car to use a DOHC engine. Also in the United States, the DOHC Offenhauser racing engine was introduced in 1933. This inline-four engine dominated North American open-wheel racing from 1934 until the 1970s.

Other early SOHC automotive engines were the 1920-1923 Wolseley Ten, the 1928-1931 MG 18/80, the 1926-1935 Singer Junior and the 1928-1929 Alfa Romeo 6C Sport. Early overhead camshaft motorcycles included the 1925-1949 Velocette K Series and the 1927-1939 Norton CS1.

1945-present[edit]

The 1946-1948 Crosley CC Four was arguably the first American mass-produced car to use an SOHC engine.[37][38][39] This small mass-production engine powered the winner of the 1950 12 Hours of Sebring.[37](p121)

Use of a DOHC configuration gradually increased after World War II, beginning with sports cars. Iconic DOHC engines of this period include the 1948-1959 Lagonda straight-six engine, the 1949–1992 Jaguar XK straight-six engine and the 1954-1994 Alfa Romeo Twin Cam inline-four engine.[40][41] The 1966-2000 Fiat Twin Cam inline-four engine was one of the first DOHC engines to use a toothed timing belt instead of a timing chain.[42]

In the 1980s, the need for increased performance while reducing fuel consumption and exhaust emissions saw increasing use of DOHC engines in mainstream vehicles, beginning with Japanese manufacturers.[40] By the mid-2000s, most automotive engines used a DOHC layout.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- Cam-in-block

- Camless

- Overhead valve engine

- Variable valve timing

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hillier, V.A.W. (2012) [First published 1966]. "2". Fundamentals of Motor Vehicle Technology (Academic text-book). Book 1. In association with: (IMI) (6th ed.). Nelson Thornes Ltd. ISBN 9781408515181.

- ^ a b Stoakes, Graham; Sykes, Eric; Whittaker, Catherine (2011). "3". Principles of Light Vehicle maintenance & repair. Heinmann Work-Based Learning. Babcock International Group and Graham Stoakes. pp. 208–209. ISBN 9780435048167.

- ^ "OHV, OHC, SOHC and DOHC (twin cam) engine - Automotive illustrated glossary". www.samarins.com. Retrieved 2018-09-20.

- ^ Harley-Davidson Twin Cam engine, Fiat Twin Cam engine, Alfa Romeo Twin Cam engine, Quad 4 engine, Lotus-Ford Twin Cam

- ^ a b c d Boddy, William (January 1964). "Random Thoughts About O.H.C." Motor Sport. London, UK: Teesdale Publishing. XL (1).

- ^ a b c d e f g "SOHC vs DOHC Valvetrains: A Comparison". www.paultan.org. Driven Communications Sdn Bhd. 22 June 2005. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ Heseltine, Richard (June 2010). Roebuck, Nigel (ed.). "Triumph Dolomite Sprint". Motor Sport. London, UK. 86 (6): 122. ISSN 0027-2019. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Lewis, Jimmy (November 2001). Edwards, David (ed.). "New for '02: Honda CR250R CRF450R". Cycle World. Hachette-Filipacchi Magazines. 40 (11): 62. ISSN 0011-4286. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "How It Works: Honda Unicam® Engines". www.honda.com. 23 January 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ "2010 Honda VFR1200A First Ride". www.moto123.com. 19 October 2009. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ a b "Dan's motorcycle 'Cam Drives'". www.dansmc.com. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Decker, John (June 1993). Oldham, Joe (ed.). "Saturday Mechanic: Replacing Your Timing Belt". Popular Mechanics. New York, NY US: Hearst. 170 (6). ISSN 0032-4558. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ a b Dorries, Elisabeth H. (2005). TechOne: Automotive Engine Repair. Clifton Park, NY US: Thompson Delmar Learning. ISBN 1-4018-5941-0. LCCN 2004057974. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ a b Pace, Harold W.; Brinker, Mark R. (2004). Vintage American Road Racing Cars 1950-1969. St. Paul MN US: MotorBooks International. p. 62. ISBN 0-7603-1783-6. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Norbye, Jan P. (1984). "Expanding on Excellence: The 5-Series and 3-Series". BMW - Bavaria's Driving Machines. Skokie, IL: Publications International. p. 191. ISBN 0-517-42464-9.

- ^ Bennett, Sean (2014-01-01). Modern Diesel Technology: Diesel Engines. Stamford, CT US: Cengage Learning. pp. 88–89, 362. ISBN 978-1-285-44296-9. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

In most commercial diesels, OHCs are gear-driven.

- ^ Boddy, William (August 1972). Boddy, William (ed.). "An Edwardian Overhead-Camshaft 25/30 Maudslay". Motor Sport. London, UK: Teesdale Publishing. XLVIII (8): 909. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ a b Culshaw, David; Horrobin, Peter (2013) [1974]. "Maudslay". The Complete Catalogue of British Cars 1895 - 1975 (e-book ed.). Poundbury, Dorchester, UK: Veloce Publishing. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-845845-83-4.

- ^ Norbye, Jan P. (1981). The complete handbook of automotive power trains. Tab Books. p. 318. ISBN 0-8306-2069-9. LCCN 79026958. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Cameron, Kevin (March 2004). "TDC: Little things". Cycle World. 43 (3): 14. ISSN 0011-4286. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Hugo (1995). "The A-Z of Motorcycles". The Encyclopedia of the Motorcycle. London, UK: Dorling Kindersley. p. 144. ISBN 0-7513-0206-6.

- ^ Walker, Mick (2003) [1991]. "4 Engine". Ducati Singles Restoration. St. Paul, MN US: Motorbooks International. p. 48. ISBN 0-7603-1734-8. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "2015 W800". www.kawasaki.eu. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Ash, Kevin (26 October 2011). "Kawasaki W800 review". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013.

- ^ A US patent 1495620 A, John Godfrey Parry Thomas, "Internal Combustion Engine", issued 1924-05-27

- ^ U.S. Patent 1,495,620

- ^ a b Boddy, William (March 1974). Boddy, William (ed.). "How Did The Leyland Eight Rate?". Motor Sport. L (3): 230. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ Brooks, Philip C. (2009). Carpenter, Rhonda; Iwalani, Kahikina (eds.). "The Mighty Sixes". The International Club for Rolls-Royce & Bentley Owners Desk Diary 2010. Tampa, FL USA: Faircount: 27, 32.

- ^ Georgano, G. N. (1982) [1968]. "Maudslay". In Georgano, G. N. (ed.). The New Encyclopedia of Motorcars 1885 to the Present (Third ed.). New York: E. P. Dutton. p. 407. ISBN 0525932542. LCCN 81-71857.

- ^ "Marr Auto Car Company". www.marrautocar.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018.

- ^ Kimes, Beverly Rae (2007). Walter L Marr: Buick's Amazing Engineer. Racemaker Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0976668343.

- ^ "1913 Isotta Fraschini 100-120 hp Tipo KM 4 Four-Seat Torpedo Tourer - Auction Lot". www.motorbase.com. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ Thorpe, Leslie Aaron (1936). A text book on aviation: the new cadet system of ground school training. 3. Aviation Press. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

The overhead camshafts are driven by bevel gears and vertical shafts known as tower shafts.

- ^ Mueller, Mike (2006). "Chapter 6 - Chariot of the Gods Duesenberg Straight Eight". American Horsepower 100 Years of Great Car Engines. St. Paul, MN USA: Motorbooks. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7603-2327-4. LCCN 2006017040. Retrieved 2015-02-02.

- ^ "Talking of sports cars: Sunbeam three-litre". Autocar. 147 (nbr 4221): 69–71. 1 October 1977.

- ^ Georgano, G.N. (1985). Cars: Early and Vintage, 1886-1930. London: Grange-Universal.

- ^ a b Simanaitis, Dennis (January 1994). Bryant, Thos L. (ed.). "Tech Tidbits". Road & Track. Newport Beach, CA US: Hachette Filipacchi Magazines. 45 (6): 121. ISSN 0035-7189.

- ^ "Crosley Engine Family Tree - Taylor Years". www.crosleyautoclub.com. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Crosley Engine Family Tree - CoBra Years". www.crosleyautoclub.com. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ a b "An Echo of the Past — the history and evolution of twin-cam engines". www.EuropeanCarWeb.com. European Car Magazine, Source Interlink Media. February 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ "Technical- Boxer History". www.alfisti.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013.

- ^ "Old Fiat ad with Aurelio Lampredi". www.kinja-img.com. Retrieved 31 January 2015.