| Mofeta moteada occidental [1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Spilogale gracilis | |

| |

| Spilogale gracilis amphialus | |

| clasificación cientifica | |

| Reino: | Animalia |

| Filo: | Chordata |

| Clase: | Mammalia |

| Pedido: | Carnivora |

| Familia: | Mephitidae |

| Género: | Spilogale |

| Especies: | S. gracilis |

| Nombre binomial | |

| Spilogale gracilis ( Merriam , 1890) | |

| |

Gama de mofeta moteada occidental | |

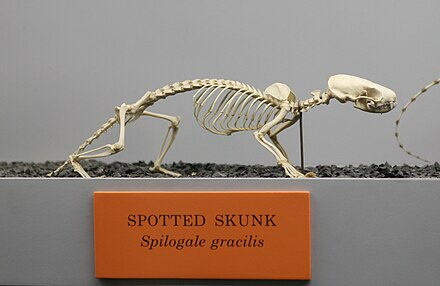

La mofeta moteada occidental ( Spilogale gracilis ) es una mofeta moteada del oeste de América del Norte.

Descripción [ editar ]

Con una longitud total de 35 a 45 cm (14 a 18 pulgadas), la mofeta moteada occidental es más pequeña que la mofeta rayada ( Mephitis mephitis). Los machos, que pesan de 336 a 734 g (11,9 a 25,9 oz), son significativamente más pesados que las hembras, de 227 a 482 g (8,0 a 17,0 oz), pero solo alrededor de un 6% más, en promedio. El adulto tiene franjas audaces de color negro y blanco cremoso, con tres franjas longitudinales a cada lado de la parte delantera del cuerpo y tres franjas verticales en las partes traseras. Un par de franjas longitudinales corre a ambos lados de la columna, y el segundo par corre sobre los hombros y se extiende hacia adelante sobre la cara. El tercer par es más bajo sobre los hombros y se curva hacia abajo en la mitad del cuerpo para formar el primer par de rayas verticales. Detrás de esto, el segundo par de rayas verticales se eleva desde las rodillas hasta la grupa, mientras que las rayas finales suelen ser poco más que manchas. [3]En casos especiales, las áreas normalmente negras del pelaje pueden aparecer en tonos de rojo o marrón, y las áreas de la mofeta que tradicionalmente parecen blancas pueden aparecer en tonos de gris o amarillo, aún no está claro qué causa la variación de color. . [4]

Las orejas son cortas y redondeadas, mientras que la cara está marcada con una mancha blanca entre los ojos y una mancha blanca debajo de cada oreja. El animal tiene una cola notablemente grande y de pelo largo, que mide de 10 a 16 cm (3,9 a 6,3 pulgadas). El pelo de la cola es mayormente negro, pero es blanco en la punta y, a veces, también en la superficie superior. Las garras de las patas delanteras son más largas y más curvas que las de las patas traseras. [3] El patrón único de manchas y rayas en blanco y negro de la mofeta moteada occidental y su pequeño tamaño las diferencia de las mofetas desnudas normales. [5]

Al igual que con otras especies relacionadas, los zorrillos manchados occidentales poseen un par de glándulas almizcleras grandes que se abren justo dentro del ano y que pueden rociar su contenido a través de la acción muscular. El almizcle es similar al de las mofetas rayadas, pero contiene 2-feniletanotiol como componente adicional y carece de algunos de los compuestos producidos por las otras especies. Se dice que estas diferencias le dan a la almizcle de mofeta moteada occidental un olor más penetrante, pero no se propagan tanto como el de las mofetas rayadas. [3]

Distribución y hábitat [ editar ]

La mofeta moteada occidental se encuentra en todo el oeste de los Estados Unidos , el norte de México y el suroeste de la Columbia Británica . Su hábitat son bosques mixtos, áreas abiertas y tierras de cultivo. Sus áreas de ocupación preferidas difieren mucho según los recursos disponibles en el área inmediata. En áreas como Idaho y Washington, prefieren las áreas ribereñas que tienen matorrales de matorrales en los que esconderse y alimentarse. Por el contrario, los miembros de las especies que viven en áreas como el este de Oregón o el norte de México a menudo se pueden encontrar cerca de acantilados y cañones. [6]

Comportamiento y dieta [ editar ]

Los zorrillos manchados occidentales son omnívoros nocturnos, que se alimentan de insectos, escorpiones, pequeños vertebrados (como ratones, ratones de campo, otros roedores, conejos, pájaros pequeños, pequeños reptiles y anfibios), raíces, granos, frutas y bayas. [7] Los insectos comunes que se comen incluyen escarabajos, saltamontes y orugas. [8] Sin embargo, se ha descubierto que consumen presas tan grandes como el petrel tormentoso ceniciento . También se alimentan de huevos y carroña. [9] Las poblaciones cercanas a estos animales a menudo tienen poblaciones de plagas disminuidas. Incluso se ha informado que consumen escorpiones en el suroeste. [10]

Golden eagles are among their few predators. They spend the day in dens, and are usually solitary, although sometimes two or three females will share a single burrow.[3] Males remain solitary during the winter.[11]

Western spotted skunks will attempt to build reserves of fat before winter. While they do not engage in true hibernation, they may sleep for several weeks during the winter.[12] During this time, females may den in groups that have been observed as large as 20.[11]

When threatened, western spotted skunks display threat behavior, stamping their fore-feet before raising their hind parts in the air and showing their conspicuous warning coloration. While they can spray by standing on their forelegs and raising their hindlegs and tail in the air, they more commonly do so with all four feet on the ground, bending their body around so that both their head and their tail face the attacker.[3][13]

Reproduction[edit]

The western spotted skunk typically reach sexual maturity much faster than other skunk species.[7] Western spotted skunks typically breed in September because that when females come into heat, although both sexes remain fertile for several months thereafter if they fail to breed early.[14][5] After fertilisation, the embryo develops to the blastocyst stage, but then becomes dormant for several months before implanting in the uterine wall around April. Including this period of delayed implantation, gestation lasts 230 to 250 days,[15] with the litter of two to five young being born in May.[14] These baby skunks are called kits.[5] At birth, the young are blind and almost hairless, weighing around 11 g (0.39 oz).[16] At around 4 or 5 months of age, young females become sexually mature and the cycle starts again.[5] Western spotted skunks have lived for almost ten years in captivity.[17]

Taxonomy and etymology[edit]

The western spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis) was first described by Clinton Hart Merriam in 1890;[18] its specific name, gracilis, is derived from the Latin for "slender".[3] There remains discussion on whether the western spotted skunk (S. gracilis) is a subspecies of the eastern spotted skunk (S. putorius), a common skunk in the eastern United States. Many support the idea that the two species are more distinctly evolved because of contrasts in morphology, breeding strategy, and molecular data.[19][14] There are currently seven recognized subspecies of S. gracilis that are indigenous to the western United States and northern Mexico, which were discovered in the late 1800s and early 1900s by biologists Merriam and Elliot.[20] The different subspecies reside in select locations within the western spotted skunk territory and therefore are acclimated to specific climates and niches in these areas.

Subspecies[edit]

Seven subspecies are generally recognized:[1]

- S. g. amphialus Dickey, 1929 — Channel Islands spotted skunk (Channel Islands of California)

- S. g. gracilis Merriam, 1890 — from south-eastern Washington to the extreme west of Oklahoma

- S. g. latifrons Merriam, 1890 — southwestern British Columbia to western Oregon

- S. g. leucoparia Merriam, 1890 — southern Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, and northern Mexico

- S. g. lucasana Merriam, 1890 — southern Baja California

- S. g. martirensis Elliot, 1903 — northern and central Baja California

- S. g. phenax Merriam, 1890 — California

Interaction with humans[edit]

Skunks are increasingly kept as house pets and can be trained to use a litter box much like a house cat (Felis catus). S. gracilis can cause problems in rural areas, as it will make dens on private property and in the attics of homes, and has a tendency to steal eggs from farmers.[10] The western spotted skunk is one of many species that are opportunistic within the expansion of human civilization, and remains neither endangered nor threatened.[7]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 623. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Cuarón, A.D.; Reid, F. & Helgen, K. (2008). "Spilogale gracilis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Verts, B.J.; Carraway, L.N. & Kinlaw, A. (2001). "Spilogale gracilis". Mammalian Species. 674: Number 674: pp. 1–10. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2001)674<0001:SG>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Carraway, L. N., Verts, B. J., & Kinlaw, A. (2001). Spilogale gracilis. Mammalian Species. doi: 10.2307/0.674.1

- ^ a b c d Webmaster, David Ratz. "Western Spotted Skunk - Montana Field Guide". fieldguide.mt.gov. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- ^ Carey, A. B., & Kershner, J. E. (1996). Spilogale gracilis in Upland Forests of Western Washington and Oregon. Northwestern Naturalist, 77(2), 29. doi: 10.2307/3536615

- ^ a b c Hakkinen, K. (2001). "Spilogale gracilis" (On-line), Animal diversity web. Accessed October 13, 2019 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Spilogale_gracilis/

- ^ Baker, R.H. & Baker, M.W. (1975). "Montane habitat used by the spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius) in Mexico". Journal of Mammalogy. 56 (3): 671–673. doi:10.2307/1379480. JSTOR 1379480.

- ^ Mciver, W. R., Carter, H. R., Harvey, A. L., Mazurkiewicz, D. M., Howard, J. A., Martin, P. L., & Mason, J. W. (2018). Avian and Skunk Predation of Ashy Storm-Petrels at Santa Cruz Island, California. Western North American Naturalist, 78(3), 421–440. doi: 10.3398/064.078.0313

- ^ a b Davis, W., Schmidly. (1994). The Mammals of Texas. Austin, TX: Texas parks and wildlife nongame and urban program.

- ^ a b University of Nebraska-Lincoln. (1977). Plains Anthropologist, 22(75), 84–84. doi: 10.1080/2052546.1977.11908814

- ^ Genoways, H. H. (1984). Jones, J. K., Jr., D. M. Armstrong, R. S. Hoffmann, and C. Jones. MAMMALS OF THE NORTHERN GREAT PLAINS. Univ. Nebraska Press, Lincoln, xii 379 pp., illustrated, 1983. Price, $32.50 (hardbound). Journal of Mammalogy, 65(4), 730–731. doi: 10.2307/1380869

- ^ Crooks, K.R. & Van Vuren, D. (1995). "Resource utilization by two insular endemic mammalian carnivores, the island fox and island spotted skunk". Oecologia. 104 (3): 301–307. Bibcode:1995Oecol.104..301C. doi:10.1007/BF00328365. PMID 28307586. S2CID 11431727.

- ^ a b c Mead, R.A. (1968). "Reproduction in western forms of the spotted skunk (genus Spilogale)". Journal of Mammalogy. 49 (3): 373–390. doi:10.2307/1378196. JSTOR 1378196. PMID 5691422.

- ^ Foreman, K.R. & Mead, R.A. (1973). "Duration of post-implantation in a western subspecies of the spotted skunk (Spilogale putorius)". Journal of Mammalogy. 54 (2): 521–523. doi:10.2307/1379146. JSTOR 1379146. PMID 4706258.

- ^ Constantine, D.G. (1968). "Gestation period in the spotted skunk". Journal of Mammalogy. 42 (3): 421–422. doi:10.2307/1377064. JSTOR 1377064.

- ^ Egoscue, H.J.; Bittmein, J.G. & Petrovich, J.A. (1970). "Some fecundity and longevity records for captive small mammals". Journal of Mammalogy. 51 (3): 622–623. doi:10.2307/1378407. JSTOR 1378407.

- ^ ITIS Report. "ITIS Standard Report: Spilogale gracilis". Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ^ Mead, R. A. (1968)[full citation needed]

- ^ Schmid, R., Wilson, D. E., & Reeder, D. M. (1993). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Taxon, 42(2), 512. doi: 10.2307/1223169

External links[edit]

- Media related to Spilogale gracilis at Wikimedia Commons

- Data related to Spilogale at Wikispecies