La lignina es una clase de polímeros orgánicos complejos que forman materiales estructurales clave en los tejidos de soporte de la mayoría de las plantas. [1] Las ligninas son particularmente importantes en la formación de las paredes celulares , especialmente en la madera y la corteza , porque confieren rigidez y no se pudren fácilmente. Químicamente, las ligninas son polímeros fabricados por reticulación de precursores fenólicos . [2]

Historia [ editar ]

La lignina fue mencionada por primera vez en 1813 por el botánico suizo AP de Candolle , quien la describió como un material fibroso, insípido, insoluble en agua y alcohol pero soluble en soluciones alcalinas débiles, y que puede precipitarse de la solución usando ácido. [3] Llamó a la sustancia "lignina", que se deriva de la palabra latina lignum , [4] que significa madera. Es uno de los abundantes mayoría de los polímeros orgánicos en la Tierra , sólo superada por la celulosa . La lignina constituye el 30% del carbono orgánico no fósil [5] y del 20 al 35% de la masa seca de madera.

La lignina está presente en las algas rojas , lo que sugiere que el ancestro común de las plantas y las algas rojas también sintetizaba lignina. Este hallazgo también sugiere que la función original de la lignina era estructural, ya que desempeña este papel en el alga roja Calliarthron , donde sostiene las articulaciones entre los segmentos calcificados . [6]

Estructura [ editar ]

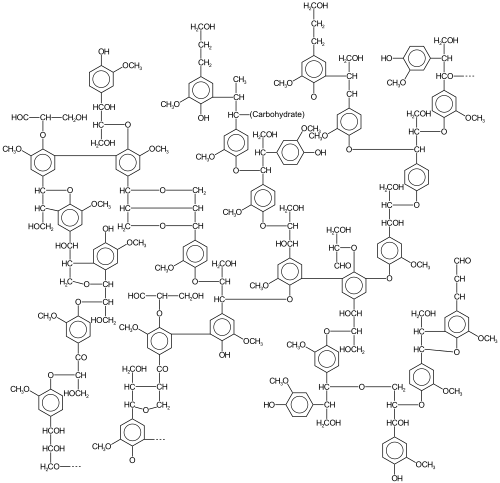

La lignina es un polímero altamente heterogéneo derivado de un puñado de lignol precursores que se entrecruzan de diversas formas. Los lignol que se reticulan son de tres tipos principales, todos derivados del fenilpropano: alcohol de coniferilo (4-hidroxi-3-metoxifenilpropano) (su radical a veces se llama guaiacilo), alcohol sinapílico (3,5-dimetoxi-4-hidroxifenilpropano) (su radical se llama a veces siringilo) y alcohol paracumarílico (4-hidroxifenilpropano) (su radical a veces se llama 4-hidroxifenilo).

Las cantidades relativas de los "monómeros" precursores varían según la fuente de la planta. En términos generales: [5]

- Las maderas duras son ricas en unidades de coniferilo y sinapilo.

- las maderas blandas son ricas en unidades de coniferilo

- las gramíneas son ricas en unidades de coniferilo y sinapilo

Las masas moleculares de la lignina superan las 10.000 u . Es hidrófobo ya que es rico en subunidades aromáticas . El grado de polimerización es difícil de medir, ya que el material es heterogéneo. Se han descrito diferentes tipos de lignina según los medios de aislamiento. [7]

Muchas hierbas tienen principalmente G, mientras que algunas palmas tienen principalmente S. [8] Todas las ligninas contienen pequeñas cantidades de monolignol incompletos o modificados, y otros monómeros son prominentes en plantas no leñosas. [9]

Función biológica [ editar ]

La lignina llena los espacios en la pared celular entre los componentes de celulosa , hemicelulosa y pectina , especialmente en los tejidos vasculares y de soporte: xilema traqueidas , elementos vasculares y células esclereideas .

La lignina juega un papel crucial en la conducción de agua y nutrientes acuosos en los tallos de las plantas . Los componentes polisacáridos de las paredes de las células vegetales son muy hidrófilos y, por tanto, permeables al agua, mientras que la lignina es más hidrófoba . La reticulación de los polisacáridos por la lignina es un obstáculo para la absorción de agua por la pared celular. Por lo tanto, la lignina hace posible que el tejido vascular de la planta conduzca el agua de manera eficiente. [10] La lignina está presente en todas las plantas vasculares , pero no en las briofitas , lo que respalda la idea de que la función original de la lignina estaba restringida al transporte de agua.

Está unido covalentemente a la hemicelulosa y, por lo tanto, reticula diferentes polisacáridos vegetales , lo que confiere resistencia mecánica a la pared celular y, por extensión, a la planta en su conjunto. [11] Su función más común es el apoyo a través del fortalecimiento de la madera (compuesta principalmente por células del xilema y fibras del esclerénquima lignificado ) en las plantas vasculares. [12] [13] [14]

Finalmente, la lignina también confiere resistencia a enfermedades al acumularse en el sitio de infiltración del patógeno, lo que hace que la célula vegetal sea menos accesible a la degradación de la pared celular. [15]

Importancia económica [ editar ]

La producción comercial mundial de lignina es una consecuencia de la fabricación de papel. En 1988, se produjeron más de 220 millones de toneladas de papel en todo el mundo. [16] Gran parte de este documento fue deslignificado; la lignina comprende aproximadamente 1/3 de la masa de lignocelulosa, el precursor del papel. Por tanto, se puede ver que la lignina se manipula a gran escala. La lignina es un impedimento para la fabricación de papel, ya que está coloreada, amarillea en el aire y su presencia debilita el papel. Una vez separada de la celulosa, se quema como combustible. Solo una fracción se utiliza en una amplia gama de aplicaciones de bajo volumen donde la forma, pero no la calidad, es importante. [17]

La pulpa mecánica o de alto rendimiento , que se utiliza para hacer papel de periódico , todavía contiene la mayor parte de la lignina presente originalmente en la madera. Esta lignina es responsable del color amarillento del papel de periódico con la edad. [4] El papel de alta calidad requiere la eliminación de lignina de la pulpa. Estos procesos de deslignificación son tecnologías centrales de la industria de fabricación de papel, así como la fuente de importantes preocupaciones ambientales. [ cita requerida ]

En la pulpa de sulfito , la lignina se elimina de la pulpa de madera como lignosulfonatos , para lo cual se han propuesto muchas aplicaciones. [18] Se utilizan como dispersantes , humectantes , estabilizadores de emulsiones y secuestrantes ( tratamiento de agua ). [19] El lignosulfonato también fue la primera familia de reductores de agua o superplastificantes que se agregaron en la década de 1930 como aditivo al concreto fresco para disminuir la relación agua-cemento (a / c ), el principal parámetro que controla la porosidad del concreto , y por lo tanto suresistencia mecánica , su difusividad y su conductividad hidráulica , todos parámetros esenciales para su durabilidad. Tiene aplicación en agente de supresión de polvo ambientalmente sostenible para carreteras. Además, se puede utilizar en la fabricación de plástico biodegradable junto con celulosa como una alternativa a los plásticos hechos con hidrocarburos si la extracción de lignina se logra a través de un proceso ambientalmente más viable que la fabricación de plástico genérico. [20]

Lignin removed by the kraft process is usually burned for its fuel value, providing energy to power the mill. Two commercial processes exist to remove lignin from black liquor for higher value uses: LignoBoost (Sweden) and LignoForce (Canada). Higher quality lignin presents the potential to become a renewable source of aromatic compounds for the chemical industry, with an addressable market of more than $130bn.[21]

Given that it is the most prevalent biopolymer after cellulose, lignin has been investigated as a feedstock for biofuel production and can become a crucial plant extract in the development of a new class of biofuels.[22][23]

Biosynthesis[edit]

Lignin biosynthesis begins in the cytosol with the synthesis of glycosylated monolignols from the amino acid phenylalanine. These first reactions are shared with the phenylpropanoid pathway. The attached glucose renders them water-soluble and less toxic. Once transported through the cell membrane to the apoplast, the glucose is removed, and the polymerisation commences.[24] Much about its anabolism is not understood even after more than a century of study.[5]

The polymerisation step, that is a radical-radical coupling, is catalysed by oxidative enzymes. Both peroxidase and laccase enzymes are present in the plant cell walls, and it is not known whether one or both of these groups participates in the polymerisation. Low molecular weight oxidants might also be involved. The oxidative enzyme catalyses the formation of monolignol radicals. These radicals are often said to undergo uncatalyzed coupling to form the lignin polymer.[25] An alternative theory invokes an unspecified biological control.[1]

Biodegradation[edit]

In contrast to other bio-polymers (e.g. proteins, DNA, and even cellulose), lignin is resistant to degradation and acid- and base-catalyzed hydrolysis. However the extent to which lignin does or does not degrade varies with species and plant tissue type. For example, syringyl (S) lignol is more susceptible to degradation by fungal decay as it has fewer aryl-aryl bonds and a lower redox potential than guaiacyl units.[26][27] Because it is cross-linked with the other cell wall components, lignin minimizes the accessibility of cellulose and hemicellulose to microbial enzymes, leading to a reduced digestibility of biomass.[10]

Some ligninolytic enzymes include heme peroxidases such as lignin peroxidases, manganese peroxidases, versatile peroxidases, and dye-decolourizing peroxidases as well as copper-based laccases. Lignin peroxidases oxidize non-phenolic lignin, whereas manganese peroxidases only oxidize the phenolic structures. Dye-decolorizing peroxidases, or DyPs, exhibit catalytic activity on a wide range of lignin model compounds, but their in vivo substrate is unknown. In general, laccases oxidize phenolic substrates but some fungal laccases have been shown to oxidize non-phenolic substrates in the presence of synthetic redox mediators.[28][29]

Lignin degradation by fungi[edit]

Well-studied ligninolytic enzymes are found in Phanerochaete chrysosporium[30] and other white rot fungi. Some white rot fungi, such as C. subvermispora, can degrade the lignin in lignocellulose, but others lack this ability. Most fungal lignin degradation involves secreted peroxidases. Many fungal laccases are also secreted, which facilitate degradation of phenolic lignin-derived compounds, although several intracellular fungal laccases have also been described. An important aspect of fungal lignin degradation is the activity of accessory enzymes to produce the H2O2 required for the function of lignin peroxidase and other heme peroxidases.[28]

Lignin degradation by bacteria[edit]

Bacteria lack most of the enzymes employed in fungal lignin degradation, yet bacterial degradation can be quite extensive.[31] The ligninolytic activity of bacteria has not been studied extensively even though it was first described in 1930. Many bacterial DyPs have been characterized. Bacteria do not express any of the plant-type peroxidases (lignin peroxidase, Mn peroxidase, or versatile peroxidases), but three of the four classes of DyP are only found in bacteria. In contrast to fungi, most bacterial enzymes involved in lignin degradation are intracellular, including two classes of DyP and most bacterial laccases.[29]

Bacterial degradation of lignin is particularly relevant in aquatic systems such as lakes, rivers, and streams, where inputs of terrestrial material (e.g. leaf litter) can enter waterways and leach dissolved organic carbon rich in lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose. In the environment, lignin can be degraded either biotically via bacteria or abiotically via photochemical alteration, and oftentimes the latter assists in the former.[32] In addition to the presence or absence of light, several of environmental factors affect the biodegradability of lignin, including bacterial community composition, mineral associations, and redox state.[33][34]

Pyrolysis[edit]

Pyrolysis of lignin during the combustion of wood or charcoal production yields a range of products, of which the most characteristic ones are methoxy-substituted phenols. Of those, the most important are guaiacol and syringol and their derivatives. Their presence can be used to trace a smoke source to a wood fire. In cooking, lignin in the form of hardwood is an important source of these two compounds, which impart the characteristic aroma and taste to smoked foods such as barbecue. The main flavor compounds of smoked ham are guaiacol, and its 4-, 5-, and 6-methyl derivatives as well as 2,6-dimethylphenol. These compounds are produced by thermal breakdown of lignin in the wood used in the smokehouse.[35]

Chemical analysis[edit]

The conventional method for lignin quantitation in the pulp industry is the Klason lignin and acid-soluble lignin test, which is standardized procedures. The cellulose is digested thermally in the presence of acid. The residue is termed Klason lignin. Acid-soluble lignin (ASL) is quantified by the intensity of its Ultraviolet spectroscopy. The carbohydrate composition may be also analyzed from the Klason liquors, although there may be sugar breakdown products (furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural).[36] or NREL[37]

A solution of hydrochloric acid and phloroglucinol is used for the detection of lignin (Wiesner test). A brilliant red color develops, owing to the presence of coniferaldehyde groups in the lignin.[38]

Thioglycolysis is an analytical technique for lignin quantitation.[39] Lignin structure can also be studied by computational simulation.[40]

Thermochemolysis (chemical break down of a substance under vacuum and at high temperature) with tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) or cupric oxide[41] has also been used to characterize lignins. The ratio of syringyl lignol (S) to vanillyl lignol (V) and cinnamyl lignol (C) to vanillyl lignol (V) is variable based on plant type and can therefore be used to trace plant sources in aquatic systems (woody vs. non-woody and angiosperm vs. gymnosperm).[42] Ratios of carboxylic acid (Ad) to aldehyde (Al) forms of the lignols (Ad/Al) reveal diagenetic information, with higher ratios indicating a more highly degraded material.[26][27] Increases in the (Ad/Al) value indicate an oxidative cleavage reaction has occurred on the alkyl lignin side chain which has been shown to be a step in the decay of wood by many white-rot and some soft rot fungi.[26][27][43][44][45]

Lignin and its models have been well examined by 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy. Owing to the structural complexity of lignins, the spectra are poorly resolved and quantitation is challenging.[46]

Further reading[edit]

- K. Freudenberg & A.C. Nash (eds) (1968). Constitution and Biosynthesis of Lignin. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Saake, Bodo; Lehnen, Ralph (2007). Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_305.pub3.

- ^ Lebo, Stuart E. Jr.; Gargulak, Jerry D.; McNally, Timothy J. (2001). "Lignin". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. Kirk‑Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/0471238961.12090714120914.a01.pub2. ISBN 978-0-471-23896-6. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ de Candolle, M.A.P. (1813). Theorie Elementaire de la Botanique ou Exposition des Principes de la Classification Naturelle et de l'Art de Decrire et d'Etudier les Vegetaux. Paris: Deterville. See p. 417.

- ^ a b E. Sjöström (1993). Wood Chemistry: Fundamentals and Applications. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-647480-0.

- ^ a b c W. Boerjan; J. Ralph; M. Baucher (June 2003). "Lignin biosynthesis". Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 54 (1): 519–549. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.031902.134938. PMID 14503002.

- ^ Martone, Pt; Estevez, Jm; Lu, F; Ruel, K; Denny, Mw; Somerville, C; Ralph, J (Jan 2009). "Discovery of Lignin in Seaweed Reveals Convergent Evolution of Cell-Wall Architecture". Current Biology. 19 (2): 169–75. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.031. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 19167225. S2CID 17409200.

- ^ "Lignin and its Properties: Glossary of Lignin Nomenclature". Dialogue/Newsletters Volume 9, Number 1. Lignin Institute. July 2001. Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2007-10-14.

- ^ Kuroda K, Ozawa T, Ueno T (April 2001). "Characterization of sago palm (Metroxylon sagu) lignin by analytical pyrolysis". J Agric Food Chem. 49 (4): 1840–7. doi:10.1021/jf001126i. PMID 11308334. S2CID 27962271.

- ^ J. Ralph; et al. (2001). "Elucidation of new structures in lignins of CAD- and COMT-deficient plants by NMR". Phytochemistry. 57 (6): 993–1003. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00109-1. PMID 11423146.

- ^ a b K.V. Sarkanen & C.H. Ludwig (eds) (1971). Lignins: Occurrence, Formation, Structure, and Reactions. New York: Wiley Intersci.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Chabannes, M.; et al. (2001). "In situ analysis of lignins in transgenic tobacco reveals a differential impact of individual transformations on the spatial patterns of lignin deposition at the cellular and subcellular levels". Plant J. 28 (3): 271–282. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01159.x. PMID 11722770.

- ^ Arms, Karen; Camp, Pamela S. (1995). Biology. Saunders College Pub. ISBN 9780030500039.

- ^ Esau, Katharine (1977). Anatomy of Seed Plants. Wiley. ISBN 9780471245209.

- ^ Wardrop; The (1969). "Eryngium sp.;". Aust. J. Botany. 17 (2): 229–240. doi:10.1071/bt9690229.

- ^ Bhuiyan, Nazmul H; Selvaraj, Gopalan; Wei, Yangdou; King, John (February 2009). "Role of lignification in plant defense". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 4 (2): 158–159. doi:10.4161/psb.4.2.7688. ISSN 1559-2316. PMC 2637510. PMID 19649200.

- ^ Rudolf Patt et al. (2005). "Pulp". Paper and Pulp. Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–92. doi:10.1002/14356007.a18_545.pub4. ISBN 9783527306732.

- ^ Higson, A; Smith, C (25 May 2011). "NNFCC Renewable Chemicals Factsheet: Lignin". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ^ "Uses of lignin from sulfite pulping". Archived from the original on 2007-10-09. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ Barbara A. Tokay (2000). "Biomass Chemicals". Ullmann's Encyclopedia Of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a04_099. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Patt, Rudolf; Kordsachia, Othar; Süttinger, Richard; Ohtani, Yoshito; Hoesch, Jochen F.; Ehrler, Peter; Eichinger, Rudolf; Holik, Herbert; Hamm (2000). Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a18_545.

- ^ "Frost & Sullivan: Full Speed Ahead for the Lignin Market with High-Value Opportunities as early as 2017".

- ^ Folkedahl, Bruce (2016), "Cellulosic ethanol: what to do with the lignin", Biomass, retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ^ Abengoa (2016-04-21), The importance of lignin for ethanol production, retrieved 2016-08-10.

- ^ Samuels AL, Rensing KH, Douglas CJ, Mansfield SD, Dharmawardhana DP, Ellis BE (November 2002). "Cellular machinery of wood production: differentiation of secondary xylem in Pinus contorta var. latifolia". Planta. 216 (1): 72–82. doi:10.1007/s00425-002-0884-4. PMID 12430016. S2CID 20529001.

- ^ Davin, L.B.; Lewis, N.G. (2005). "Lignin primary structures and dirigent sites". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 16 (4): 407–415. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2005.06.011. PMID 16023847.

- ^ a b c Vane, C. H.; et al. (2003). "Biodegradation of Oak (Quercus alba) Wood during Growth of the Shiitake Mushroom (Lentinula edodes): A Molecular Approach". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (4): 947–956. doi:10.1021/jf020932h. PMID 12568554.

- ^ a b c Vane, C. H.; et al. (2006). "Bark decay by the white-rot fungus Lentinula edodes: Polysaccharide loss, lignin resistance and the unmasking of suberin". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 57 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2005.10.004.

- ^ a b Advances in applied microbiology. Vol. 82. Gadd, Geoffrey M., Sariaslani, Sima. Oxford: Academic. 2013. pp. 1–28. ISBN 9780124076792. OCLC 841913543.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ a b de Gonzalo, Gonzalo; Colpa, Dana I.; Habib, Mohamed H.M.; Fraaije, Marco W. (2016). "Bacterial enzymes involved in lignin degradation". Journal of Biotechnology. 236: 110–119. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.08.011. PMID 27544286.

- ^ Tien, M (1983). "Lignin-Degrading Enzyme from the Hymenomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium Burds". Science. 221 (4611): 661–3. Bibcode:1983Sci...221..661T. doi:10.1126/science.221.4611.661. PMID 17787736. S2CID 8767248.

- ^ Pellerin, Brian A.; Hernes, Peter J.; Saraceno, JohnFranco; Spencer, Robert G. M.; Bergamaschi, Brian A. (May 2010). "Microbial degradation of plant leachate alters lignin phenols and trihalomethane precursors". Journal of Environmental Quality. 39 (3): 946–954. doi:10.2134/jeq2009.0487. ISSN 0047-2425. PMID 20400590.

- ^ Hernes, Peter J. (2003). "Photochemical and microbial degradation of dissolved lignin phenols: Implications for the fate of terrigenous dissolved organic matter in marine environments". Journal of Geophysical Research. 108 (C9): 3291. Bibcode:2003JGRC..108.3291H. doi:10.1029/2002JC001421. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ "Persistence of Soil Organic Matter as an Ecosystem Property". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ^ Dittmar, Thorsten (2015-01-01). "Reasons Behind the Long-Term Stability of Dissolved Organic Matter". Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter. pp. 369–388. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-405940-5.00007-8. ISBN 9780124059405.

- ^ Wittkowski, Reiner; Ruther, Joachim; Drinda, Heike; Rafiei-Taghanaki, Foroozan "Formation of smoke flavor compounds by thermal lignin degradation" ACS Symposium Series (Flavor Precursors), 1992, volume 490, pp 232–243. ISBN 978-0-8412-1346-3.

- ^ TAPPI. T 222 om-02 - Acid-insoluble lignin in wood and pulp

- ^ Sluiter, A., Hames, B., Ruiz, R., Scarlata, C., Sluiter, J., Templeton, D., Crocker, D. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass. Technical Report NREL/TP-510-42618, U.S. Department of Energy, 2008. [1]

- ^ Lignin production and detection in wood. John M. Harkin, U.S. Forest Service Research Note FPL-0148, November 1966 (article)

- ^ Lange, B. M.; Lapierre, C.; Sandermann, Jr (1995). "Elicitor-Induced Spruce Stress Lignin (Structural Similarity to Early Developmental Lignins)". Plant Physiology. 108 (3): 1277–1287. doi:10.1104/pp.108.3.1277. PMC 157483. PMID 12228544.

- ^ Glasser, Wolfgang G.; Glasser, Heidemarie R. (1974). "Simulation of Reactions with Lignin by Computer (Simrel). II. A Model for Softwood Lignin". Holzforschung. 28 (1): 5–11, 1974. doi:10.1515/hfsg.1974.28.1.5. S2CID 95157574.

- ^ Hedges, John I.; Ertel, John R. (February 1982). "Characterization of lignin by gas capillary chromatography of cupric oxide oxidation products". Analytical Chemistry. 54 (2): 174–178. doi:10.1021/ac00239a007. ISSN 0003-2700.

- ^ Hedges, John I.; Mann, Dale C. (1979-11-01). "The characterization of plant tissues by their lignin oxidation products". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 43 (11): 1803–1807. Bibcode:1979GeCoA..43.1803H. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(79)90028-0. ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ Vane, C. H.; et al. (2001). "The effect of fungal decay (Agaricus bisporus) on wheat straw lignin using pyrolysis–GC–MS in the presence of tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)". Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis. 60 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1016/s0165-2370(00)00156-x.

- ^ Vane, C. H.; et al. (2001). "Degradation of Lignin in Wheat Straw during Growth of the Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) Using Off-line Thermochemolysis with Tetramethylammonium Hydroxide and Solid-State 13C NMR". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49 (6): 2709–2716. doi:10.1021/jf001409a. PMID 11409955.

- ^ Vane, C. H.; et al. (2005). "Decay of cultivated apricot wood (Prunus armeniaca) by the ascomycete Hypocrea sulphurea, using solid state 13C NMR and off-line TMAH thermochemolysis with GC–MS". International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 55 (3): 175–185. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2004.11.004.

- ^ Ralph, John; Landucci, Larry L. (2010). "NMR of Lignin and Lignans". Lignin and Lignans: Advances in Chemistry. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis. pp. 137–244. ISBN 9781574444865.

External links[edit]

- Tecnaro website