Las masacres de Renania , también conocidas como las persecuciones de 1096 o Gzerot Tatnó [1] (en hebreo : גזרות תתנ"ו , "Edictos de 4856" en hebreo), fueron una serie de asesinatos en masa de judíos perpetrados por turbas de cristianos alemanes de la Cruzada del Pueblo en el año 1096, o según el calendario judío 4856. La masacre es vista como la primera de una secuencia de eventos antisemitas en Europa que culminaron en el Holocausto . [2]

Los líderes prominentes de los cruzados involucrados en las masacres incluyeron a Pedro el Ermitaño y especialmente al Conde Emicho . [3] Como parte de esta persecución, la destrucción de las comunidades judías en Speyer , Worms y Mainz se señaló como el "Hurban Shum" (Destrucción de Shum ). [4] Estas fueron nuevas persecuciones de los judíos en las que los cruzados campesinos de Francia y Alemania atacaron a las comunidades judías. Varios historiadores se refieren a los eventos antisemitas como " pogromos ". [5]

Antecedentes [ editar ]

La predicación de la Primera Cruzada inspiró un estallido de violencia antijudía. En algunas partes de Francia y Alemania, los judíos eran percibidos como enemigos tanto como los musulmanes: se les consideraba responsables de la crucifixión y eran más visibles de inmediato que los musulmanes distantes. Muchas personas se preguntaron por qué deberían viajar miles de millas para luchar contra los no creyentes cuando ya había no creyentes más cerca de casa. [6]

También es probable que los cruzados estuvieran motivados por su necesidad de dinero. Las comunidades de Renania eran relativamente ricas, tanto por su aislamiento como porque no estaban restringidas ya que los católicos estaban en contra de los préstamos . Muchos cruzados tuvieron que endeudarse para comprar armamento y equipo para la expedición; Dado que el catolicismo occidental prohibía estrictamente la usura , muchos cruzados se vieron inevitablemente endeudados con los prestamistas judíos. Habiéndose armado asumiendo la deuda, los cruzados racionalizaron la matanza de judíos como una extensión de su misión católica. [7]

No había habido un movimiento tan amplio contra los judíos por parte de los católicos desde las expulsiones masivas y las conversiones forzadas del siglo VII. Si bien había habido una serie de persecuciones regionales de judíos por parte de católicos, como la de Metz en 888, un complot contra los judíos en Limoges en 992, una ola de persecución antijudía por parte de movimientos milenarios cristianos (que creían que Jesús era inmediatamente descender del cielo) en el año 1000, y la amenaza de expulsión de Trier en 1066; todos estos son vistos "en los términos tradicionales de ilegalización gubernamental en lugar de ataques populares desenfrenados". [8] También muchos movimientos contra los judíos (como conversiones forzadas por el rey Roberto el Piadoso de Francia,Ricardo II, duque de Normandía , y Enrique II, emperador del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico alrededor de 1007-1012) habían sido anulados por el papado del catolicismo romano o sus obispos. [8] Las pasiones despertadas en la población católica por el llamado de Urbano II a la primera cruzada llevaron la persecución de los judíos a un nuevo capítulo de la historia en el que estas limitaciones anteriores ya no se sostenían.

40 años después, el historiador judío Solomon bar Simson registró una perspectiva relevante sobre el alcance del antisemitismo de la época. Dijo que Godofredo de Bouillon juró

para emprender este viaje solo después de vengar la sangre del crucificado derramando sangre judía y erradicando por completo cualquier rastro de los que llevaban el nombre de 'judío', apaciguando así su propia ira ardiente. [9]

El emperador Enrique IV (después de ser notificado de la promesa por Kalonymus Ben Meshullam , el líder judío en Mainz ) emitió una orden prohibiendo tal acción. Godfrey afirmó que nunca tuvo la intención de matar judíos, pero la comunidad de Mainz y Colonia le envió un soborno cobrado de 500 marcos de plata . [10]

Sigebert de Gembloux escribió que antes de que pudiera librarse "una guerra en nombre del Señor" era esencial que los judíos se convirtieran; los que resistieron fueron "privados de sus bienes, masacrados y expulsados de las ciudades". [10]

Los primeros estallidos de violencia se produjeron en Francia. Según una crónica contemporánea de eventos escrita por un autor anónimo en Mainz:

Primero se levantaron los oficiales, los nobles y la gente común que estaba en la tierra de Francia [Sarefat] que se reunieron en consejo y conspiraron… para dejar despejado el camino a seguir hacia Jerusalén. [10]

Ricardo de Poitiers escribió que la persecución judía estaba muy extendida en Francia al comienzo de las expediciones al este. El cronista anónimo de Mainz admiraba a los judíos:

En el momento en que las comunidades [judías] de Francia se enteraron [de estas cosas], temblando ... se apoderaron de ellas. Escribieron cartas y enviaron mensajeros a todas las comunidades alrededor del río Rin, [en el sentido de] que ayunaran ... y buscaran misericordia de Aquel que habita en las alturas, para que Él pudiera salvarlos de sus manos. Cuando la carta llegó a los santos en la tierra [del Rin], es decir, los hombres de renombre ... en Mainz, respondieron [a sus hermanos en] Francia de la siguiente manera: 'Las comunidades han decretado un ayuno. Hemos hecho lo que era nuestro [hacer]. Que el Señor nos salve y que Él los salve a ustedes de todo dolor y opresión [que puedan sobrevenir] sobre ustedes. Tenemos mucho miedo ''. [10]

En junio y julio de 1095, las comunidades judías de Renania (al norte de las principales zonas de partida en Neuss , Wevelinghoven , Altenahr , Xanten y Moers ) fueron atacadas, pero no se registró el liderazgo y la membresía de estos grupos cruzados. [11] Algunos judíos se dispersaron hacia el este para escapar de la persecución. [12]

Además de la sospecha generalizada de los católicos hacia los judíos en ese momento, cuando los miles de miembros franceses de la Cruzada Popular llegaron al Rin, se habían quedado sin provisiones. [13] Para reabastecer sus suministros, comenzaron a saquear alimentos y propiedades judías mientras intentaban obligarlos a convertirse al catolicismo. [13]

No todos los cruzados que se habían quedado sin suministros recurrieron al asesinato; algunos, como Pedro el Ermitaño , utilizaron la extorsión en su lugar. Si bien ninguna fuente afirma que predicó contra los judíos, llevó consigo una carta de los judíos de Francia a la comunidad de Tréveris . La carta los instó a proporcionar provisiones a Peter y sus hombres. El bar de Solomon, Simson Chronicle, registra que estaban tan aterrorizados por la aparición de Peter en las puertas que aceptaron de inmediato satisfacer sus necesidades. [10] Cualquiera que fuera la posición de Pedro sobre los judíos, los hombres que decían seguirlo se sentían libres de masacrar judíos por su propia iniciativa, para saquear sus posesiones. [10] A veces, los judíos sobrevivían al ser sometidos a bautismos involuntarios, como enRatisbona , donde una turba de cruzados rodeó a la comunidad judía, la obligó a entrar en el Danubio y realizó un bautismo masivo. Después de que los cruzados abandonaron la región, estos judíos volvieron a practicar el judaísmo. [8]

Según David Nirenberg , [14] los eventos de 1096 en Renania "ocupan un lugar significativo en la historiografía judía moderna y a menudo se presentan como el primer ejemplo de un antisemitismo que de ahora en adelante nunca será olvidado y cuyo clímax fue el Holocausto ". [15]

Folkmar y Gottschalk [ editar ]

En la primavera de 1096, una serie de pequeñas bandas de caballeros y campesinos, inspiradas en la predicación de la Cruzada, partieron de varias partes de Francia y Alemania ( Worms y Colonia ). La cruzada del sacerdote Folkmar , que comenzó en Sajonia , persiguió a los judíos en Magdeburgo y más tarde, el 30 de mayo de 1096 en Praga en Bohemia . El obispo católico Cosmas intentó evitar conversiones forzadas, y toda la jerarquía católica en Bohemia predicó contra tales actos. [8] Duque Bretislaus IIestaba fuera del país y las protestas de los funcionarios de la Iglesia Católica no pudieron detener a la multitud de cruzados. [8]

La jerarquía de la Iglesia católica en su conjunto condenó la persecución de los judíos en las regiones afectadas (aunque sus protestas tuvieron poco efecto). Los sacerdotes de la parroquia fueron especialmente vocales (solo un monje, llamado Gottschalk, está registrado como uniéndose y alentando a la turba). [8] El cronista Hugo de Flavigny registró cómo se ignoraron estos llamamientos religiosos, escribiendo:

Ciertamente parece asombroso que en un solo día en muchos lugares diferentes, movidos al unísono por una inspiración violenta, tales masacres hayan tenido lugar, a pesar de su desaprobación generalizada y su condena como contrarias a la religión. Pero sabemos que no pudieron evitarse ya que se produjeron ante la excomunión impuesta por numerosos clérigos, y ante la amenaza de castigo por parte de muchos príncipes. [8]

En general, las turbas de cruzados no temían represalias, ya que los tribunales locales no tenían la jurisdicción para perseguirlos más allá de su localidad ni tenían la capacidad de identificar y enjuiciar a las personas fuera de la turba. [8] Las súplicas del clero fueron ignoradas por motivos similares (no se presentaron casos contra individuos para excomunión) y la turba creía que cualquiera que predicara misericordia a los judíos lo hacía solo porque había sucumbido al soborno judío. [8]

Gottschalk, el monje, dirigió una cruzada desde Renania y Lorena hasta Hungría , atacando ocasionalmente a las comunidades judías en el camino. A finales de junio de 1096, el rey Coloman de Hungría dio la bienvenida a la turba cruzada de Gottschalk , pero pronto empezaron a saquear el campo y provocar un desorden de borrachos. El Rey luego exigió que se desarmaran. Una vez aseguradas sus armas, los húngaros enfurecidos cayeron sobre ellos y "toda la llanura se cubrió de cadáveres y sangre". [dieciséis]

El sacerdote Folkmar y sus sajones también encontraron un destino similar de parte de los húngaros cuando comenzaron a saquear pueblos allí porque "se incitó a la sedición". [11] [16]

Emicho [ editar ]

La más grande de estas cruzadas, y la más involucrada en atacar a los judíos, fue la dirigida por el Conde Emicho . Partiendo a principios del verano de 1096, un ejército de unos 10.000 hombres, mujeres y niños avanzó a través del valle del Rin, hacia el río Meno y luego hacia el Danubio . A Emicho se unieron Guillermo el Carpintero y Drogo de Nesle , entre otros de Renania, el este de Francia, Lorena, Flandes e incluso Inglaterra .

El emperador del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico Enrique IV , ausente en el sur de Italia , ordenó que se protegiera a los judíos cuando se enteró de la intención de Emicho. Después de que algunos judíos fueran asesinados en Metz en mayo, John, obispo de Speyer, dio refugio a los habitantes judíos. Aún así, 12 judíos de Speyer fueron asesinados por cruzados el 3 de mayo. [10] El obispo de Worms también intentó albergar a judíos, pero los cruzados irrumpieron en su palacio episcopal y mataron a los judíos en su interior el 18 de mayo. Al menos 800 judíos fueron masacrados. en Worms cuando rechazaron el bautismo católico. [10] [17]

La noticia de la cruzada de Emicho se difundió rápidamente y el obispo Ruthard le impidió entrar en Mainz el 25 de mayo . Emicho también tomó una ofrenda de oro levantada por los judíos de Mainz con la esperanza de ganarse su favor y su seguridad. [10] El obispo Ruthard trató de proteger a los judíos ocultándolos en su palacio ligeramente fortificado. Sin embargo, Emicho no impidió que sus seguidores ingresaran a la ciudad [10] el 27 de mayo y se produjo una masacre. Muchos entre la clase empresarial cristiana (los burgueses ) en Mainz, tenían lazos de trabajo con judíos y les dieron refugio de las turbas (como habían hecho los burgueses en Praga). [8]Los burgueses de Mainz se unieron a la milicia del obispo y el burgrave (el gobernador militar de la ciudad) para luchar contra las primeras oleadas de cruzados. Esta posición tuvo que ser abandonada cuando los cruzados siguieron llegando en números cada vez mayores, [8] y la milicia del obispo junto con el propio obispo huyeron y dejaron a los judíos para que fueran masacrados por los cruzados. [18] A pesar del ejemplo de los burgueses, muchos ciudadanos comunes en Mainz y otras ciudades se vieron atrapados en el frenesí y se unieron a la persecución y el pillaje. [8] Mainz fue el lugar de mayor violencia, con al menos 1.100 judíos (y posiblemente más) muertos por las tropas de Clarambaud y Thomas. [10]Un hombre, llamado Isaac, se convirtió a la fuerza, pero más tarde, atormentado por la culpa, mató a su familia y se quemó vivo en su casa. Otra mujer, Rachel, mató a sus cuatro hijos con sus propias manos para que los cruzados no los mataran cruelmente.

Eliezer ben Nathan , un cronista judío de la época, parafraseó Habacuc 1: 6 y escribió sobre

extranjeros crueles, feroces y veloces, franceses y alemanes… [que] se pusieron cruces en la ropa y fueron más abundantes que langostas sobre la faz de la tierra. [10]

El 29 de mayo Emicho llegó a Colonia , donde la mayoría de los judíos ya se habían ido o estaban escondidos en casas cristianas. En Colonia, otras bandas más pequeñas de cruzados se reunieron con Emicho y se fueron con bastante dinero tomado de los judíos allí. Emicho continuó hacia Hungría, pronto se unieron algunos suevos . Coloman de Hungría se negó a permitirles pasar por Hungría. El conde Emicho y sus guerreros sitiaron Moson (o Wieselburg), en Leitha . Esto llevó a Coloman a prepararse para huir a Rusia, pero la moral de la mafia cruzada comenzó a fallar, lo que inspiró a los húngaros, y la mayoría de la mafia fue asesinada o ahogada en el río. El conde Emicho y algunos de los líderes escaparon a Italia o regresaron a sus propios hogares.[16] William el Carpintero y otros sobrevivientes finalmente se unieron a Hugh de Vermandois y al cuerpo principal de caballeros cruzados. El emperador del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico Enrique IV anuló la ley de la Iglesia y permitió que los judíos convertidos por la fuerza volvieran al judaísmo. [19]

Ataques posteriores a judíos [ editar ]

Más tarde, en 1096, Godofredo de Bouillon también recaudó tributos de los judíos en Mainz y Colonia, y habría participado él mismo en pogromos si Enrique IV no le hubiera ordenado que no lo hiciera. [20] El profesor de la Universidad de Saint Louis Thomas F. Madden , autor de A Concise History of the Crusades , afirma que los defensores judíos de Jerusalén se retiraron a su sinagoga para "prepararse para la muerte" una vez que los cruzados habían traspasado los muros exteriores de la ciudad durante el asedio de 1099 . [21] La crónica de Ibn al-Qalanisi menciona que el edificio fue incendiado mientras los judíos todavía estaban dentro. [22]Se informó que los cruzados levantaron sus escudos y cantaron "¡Cristo te adoramos!" mientras rodeaban el complejo ardiente ". [23] Sin embargo, una carta judía contemporánea escrita poco después del asedio no menciona la sinagoga en llamas. Pero jugando con el cisma religioso entre las dos sectas del judaísmo, [24] el arabista SD Goitein especula que La razón por la que el incidente no aparece en la carta es porque fue escrito por judíos caraítas y la sinagoga pertenecía a judíos rabínicos . [25]

Después del asedio, los judíos capturados de la Cúpula de la Roca , junto con los cristianos nativos, fueron obligados a limpiar la ciudad de los muertos. [26] Tancredo tomó a algunos judíos como prisioneros de guerra y los deportó a Apuleia en el sur de Italia. Varios de estos judíos no llegaron a su destino final porque "Muchos de ellos [...] fueron arrojados al mar o decapitados en el camino". [26] Numerosos judíos y sus libros sagrados (incluido el Códice de Alepo ) fueron rescatados por Raimundo de Toulouse . [27] La comunidad judía caraíta de Ashkelon (Ascalon) se acercó a sus correligionarios en Alejandría.pagar primero los libros sagrados y luego rescatar bolsillos de judíos durante varios meses. [26] Todos los que pudieron ser rescatados fueron liberados en el verano de 1100. Los pocos que no pudieron ser rescatados fueron convertidos al catolicismo o asesinados. [28] La Primera Cruzada encendió una larga tradición de violencia organizada contra los judíos en la cultura europea. El dinero judío también se utilizó en Francia para financiar la Segunda Cruzada ; los judíos también fueron atacados en muchos casos, pero no en la escala de los ataques de 1096. En Inglaterra, la Tercera Cruzada fue el pretexto para la expulsión de los judíos y la confiscación de su dinero. Las cruzadas de los dos pastores, en 1251y 1320, también vio ataques contra judíos en Francia; el segundo en 1320 también atacó y mató a judíos en Aragón .

Respuesta de la Iglesia Católica [ editar ]

| Parte de una serie sobre |

| Antisemitismo |

|---|

|

The massacre of the Rhineland Jews by the People's Crusade and other associated persecutions were condemned by the leaders and officials of the Catholic Church.[29] The Church and its members had previously carried out policies to protect the presence of Jews in Christian culture. For example, the twenty-five letters regarding the Jews of Pope Gregory I from the late sixth century became the primary texts for the canons, or Church laws, which were implanted to not only regulate Jewish life in Europe but also to protect it.[30] These policies did have limits to them; the Jews were granted protection and the right to their faith if they did not threaten Christianity and remained entirely submissive to Christian rule. These regulations were enacted in a letter by Pope Alexander II in 1063.[31] Their goal was to define the place of the Jews in Christian society. The Dispar nimirum of 1060, was the late eleventh-century papal policy concerning the Jews. It rejected acts of violence and punishments of the Jews, and it enforced the idea of protecting the Jews because they were not the enemy of the Christians. This papal policy aimed at creating a balance of privilege and restrictions on Jews so that the Christians did not see their presence as a threat. Sixty years after the Dispar nimirum, inspired by the atrocities of the First Crusade, the Sicut Judaeis was issued.[30] It was a more detailed and organized text of the position of the papacy concerning the treatment of Jews. This text was enacted by Pope Calixtus II in 1120. It defined the limits of the Jews' eternal servitude and continued the reinforcement of the Jews' right to their faith.

The bishops of Mainz, Speyer, and Worms had attempted to protect the Jews of those towns within the walls of their palaces. In 1084 Rüdiger Huzmann (1073–1090), bishop of Speyer, established an area for the Jews to live, to protect them from potential violence. Rüdiger's successor, Bishop John, continued the protection of Jews during the First Crusade. During the attack on Speyer, John saved many of the Jews, providing them protection in his castle. Bishop John had the hands of many attackers cut off.[32] Archbishop Ruthard of Mainz tried to save the Jews by gathering them in his courtyard; this was unsuccessful as Emicho and his troops stormed the palace. Ruthard managed to save a small number of Jews by putting them on boats in the Rhine.[32] The Archbishop of Cologne, Hermann II, sent many of the Jews to outlying villages, so that they would be safe from Crusaders. The archbishop of Trier was less effective; he favored protecting the Jews from violence, but during the attack on Trier, he hid and did not take any action to help them. Some bishops, like Albrecht of Magdeburg (1513–1545), went as far as offering the Crusaders silver to spare the Jews.[32]

After the First Crusade, there was a continued effort made by the popes to protect the Jews, so that violence that occurred in the Rhineland Valley would not reoccur. In 1272, Pope Gregory X stated that the Jews "are not capable of harming Christians, nor do they know how to do so."[31] Popes continually assured the Christians people that the Jews were not the enemy, but the Saracens were because they opposed Christianity, and Jews would only become the enemy if they challenged the religion. Following Gregory X's lead, Pope Benedict XIII clearly stated to the Christian people how to treat the Jews. "Jews are never to be burdened beyond the limits of the present constitution. [They are not] to be molested, to be offered in their persons, or to have their goods seized… [Rather, they are to be treated] humanely and with clemency…"[31] Benedict enforced the privileges given to the Jews by warning the Christians that their actions toward the Jewish people must not violate those given to them by the Church.

Fifty years later, when St. Bernard of Clairvaux was urging recruitment for the Second Crusade, he specifically criticized the attacks on Jews that had occurred in the First Crusade. Though Clairvaux considered the Jews to be "personae non gratae," he condemned in his letters the crusaders' attacks on the Jews and ordered protection for Jewish communities.[33] There is debate on Bernard's exact motivations: he may have been disappointed that the People's Crusade devoted so much time and resources to attacking the Jews of Western Europe while contributing almost nothing to the attempt to retake the Holy Land itself, the result being that Bernard was urging the knights to maintain focus on the goal of protecting Catholic interests in the Holy Land. It is equally possible that Bernard held the belief that forcibly converting the Jews was immoral or perceived that greed motivated the original Rhineland massacre: both sentiments are echoed in the canon of Albert of Aachen in his chronicle of the First Crusade. Albert of Aachen's view was that the People's Crusaders were uncontrollable semi-Catholicized country-folk (citing the "goose incident," which Hebrew chronicles corroborate)[further explanation needed] who massacred hundreds of Jewish women and children and that the People's Crusaders were themselves slaughtered by Turkish forces in Asia Minor.[34]

Jewish reactions[edit]

News of the attacks spread quickly and reached the Jewish communities in and around Jerusalem long before the crusaders themselves arrived. However, Jews were not systematically killed in Jerusalem, despite being caught up in the general indiscriminate violence caused by the crusaders once they reached the city.

The Hebrew chronicles portray the Rhineland Jews as martyrs who willingly sacrificed themselves in order to honour God and to preserve their own honour.[35]

Sigebert of Gembloux wrote that most of those Jews who converted before the crusader threat later returned to Judaism.[10]

In the years following the crusade, the Jewish communities were faced with troubling questions about murder and suicide, which were normally sins for Jews just as they were for Catholics. The Rhineland Jews looked to historical precedents since Biblical times to justify their actions: the honourable suicide of Saul, the Maccabees revolt against Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the suicide pact at Masada, and the Bar Kochba revolt were seen as justifiable deaths in the face of a stronger enemy.[36] Despite this, the suicidal and homicidal nature of the Rhineland Jews' actions largely separated the events of 1096 from previous incidents in Jewish history. While the events of Masada most closely parallel those of the Rhineland Massacres, it is important to note that the dramatic suicides of that event were often downplayed by Rabbinic scholars, even to the point of Masada's total omission from some Rabbinic histories.[37] Consequently, the deaths of the Rhineland Jews still held a great deal of novelty and presented confusion for both contemporary and subsequent theologians and historians.

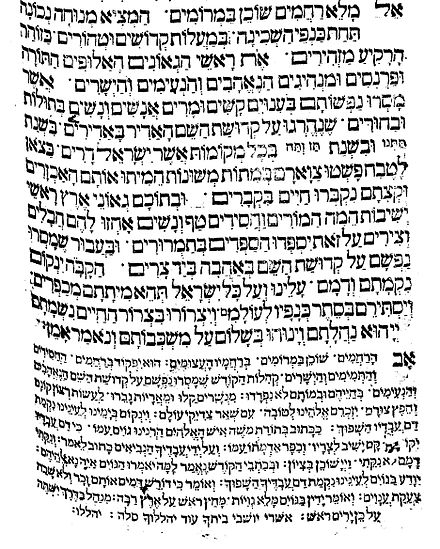

The Biblical moment that was most commonly evoked by chroniclers of the Rhineland Massacres was the Binding of Isaac, to which several allusions appear throughout the major primary sources, the Mainz Anonymous, the Soloman bar Simson Chronicle, and the Eliezer bar Nathan Chronicle (though allusions to this moment persist beyond these sources, and even in to more modern interpretations).[3] Although it was the most common Biblical reference, the details of the Binding of Isaac presented significant dissimilarities (alongside definite parallels) that put the actions of the Rhineland Jewry at odds with the Biblical narrative. While Isaac was spared from sacrifice by divine intervention, the Jews of the Rhineland committed their ritual suicide to its end. This influenced novel interpretations of the binding of Isaac. The Soloman bar Simson Chronicle interprets the sacrifice of the Rhineland Jews as a similar, though even greater expression of righteousness and piety than that of Abraham, a theme echoed throughout other chronicles of the events. Similarly, a preexisting alternative Midrashic reading of the Binding of Isaac claiming that Isaac truly was sacrificed gained a newfound popularity following the events of 1096.[38] Still, a total synthesis of the Binding of Isaac (particularly as a condemnation of human sacrifice) with the ritual deaths of 1096 was never quite achieved, and remains an inconsistency between Jewish theology and historical practice.

Several 20th century Jewish authors have related the events of 1096 to an underlying theme of human sacrifice.[38] Historian Israel Yuval understood these choices as a manifestation of a Messianic theology that was uniquely tied to medieval Jews living in the midst of Latin Christendom. This theology understood the Messiah's coming as a time of vengeance against those who transgressed against God and the Jewish people, as well as a process that was sensitive to the blood of Jewish martyrs.[38] Such ideas are alluded to in the Sefer Hasidim, a work of the twelfth century consisting of an amalgamation of Rabbinic teachings common to the era and the centuries immediately preceding it. Additionally relevant was a medieval Ashkenazi genealogical interpretation of Christians as descendants of the Biblical Esau (referred to as Edomites), over whom the Jews (the descendants of Jacob) would eventually succeed and gain dominion. Following from this, the events of 1096 presented an opportunity for the Rhineland Jews to ritually offer their deaths as an example of Christian transgression and spur the Messianic Age – an analysis supported by the frequent ritual tone and symbolism employed by Jewish chroniclers while describing the deaths, and their somewhat lesser interest for Jews who simply died by Christian hands directly. This included frequent descriptions of suicides occurring within synagogues (which were on occasion burning), and the shedding of blood on the Holy Ark.[38] Despite this, somewhat more post hoc explanations provided by Medieval Jewish chroniclers also existed. Most often, the homicide of the Rhineland children was explained by the adage "lest they dwell among the Gentiles; it is better that they die innocent and not guilty", meaning that it was better to kill Jewish children and prevent them from losing their religion, then allow them to die later as a non-Jew. The descriptions of Jewish parents killing their children was shocking to Christian ears, and may have served as fuel for later accusations of blood libel.[38]

Prior to the Crusades, the Jews were divided among three major areas which were largely independent of one another. These were the Jews living in Islamic nations (still the majority), those in the Byzantine Empire and those in the Roman Catholic West. With the persecutions that began around 1096, a new awareness of the entire people took hold across all of these groups, reuniting the three separate strands.[39]

In the late 19th century, Jewish historians used the episode as a demonstration of the need for Zionism (that is, for a new Jewish state).[40]

References[edit]

- ^ David Nirenberg, 'The Rhineland Massacres of Jews in the First Crusade, Memories Medieval and Modern', in Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory, Historiography, p.279-310

- ^ David Nirenberg (2002). Gerd Althoff (ed.). Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory, Historiography. Johannes Fried. Cambridge University Press. pp. 279–. ISBN 978-0-521-78066-7.

- ^ a b Chazan, Robert (1996). European Jewry and the First Crusade. U. of California Press. pp. 55–60, 127. ISBN 9780520917767.

- ^ Shum Hebrew: שו"ם were the letters of the three towns as pronounced at the time in old French: Shaperra, Wermieza and Magenzza.

- ^ Sources describing these attacks as pogroms include:

- Richard S. Levy. Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia Of Prejudice And Persecution, ABC-CLIO, 2005, ISBN 9781851094394. p. 153.

- Christopher Tyerman. God's War: A New History of the Crusades, Harvard University Press, 2006, ISBN 9780674023871, p. 100.

- Israel Jacob Yuval. Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, University of California Press, 2008, ISBN 9780520258181, p. 186.

- Nikolas Jaspert. The Crusades, Taylor & Francis, 2006, ISBN 9780415359672, p. 39.

- Louis Arthur Berman. The Akedah: The Binding of Isaac, Jason Aronson, 1997, ISBN 9781568218991, p. 92.

- Anna Sapir Abulafia, "Crusades", in Edward Kessler, Neil Wenborn. A Dictionary of Jewish-Christian Relations, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 9780521826921, p. 116.

- Ian Davies. Teaching the Holocaust: Educational Dimensions, Principles and Practice, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000, ISBN 9780826448514, p. 17.

- Avner Falk. A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1996, ISBN 9780838636602, p. 410.

- Hugo Slim. Killing Civilians: Method, Madness, and Morality in War, Columbia University Press, 2010, ISBN 9780231700375, p. 47.

- Richard A. Fletcher. The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity, University of California Press, 1999, ISBN 9780520218598, p. 318.

- David Biale. Power & Powerlessness in Jewish History. Random House, 2010, ISBN 9780307772534, p. 65.

- I. S. Robinson. Henry IV of Germany 1056–1106, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 9780521545907, p. 318.

- Will Durant. The Age of Faith. The Story of Civilization 4, Simon & Schuster, 1950, p. 391.

- ^ Christopher Tyerman, The Crusades, p.99

- ^ Hans Mayer. "The Crusades" (Oxford University Press: 1988) p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Salo Wittmayer Baron (1957). Social and Religious History of the Jews, Volume 4. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Patrick J. Geary, ed. (2003). Readings in Medieval History. Toronto: Broadview Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Norman Golb (1998). The Jews in Medieval Normandy: a social and intellectual history. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b John France (1997). Victory in the East: A Military History of the First Crusade. Cambridge University Press, 1994. p. 92.

- ^ Robert S. Robins, Jerrold M. Post (1997). Political Paranoia: The Psychopolitics of Hatred. Yale College. p. 168.

- ^ a b Max I. Dimont (1984). The Amazing Adventures of the Jewish People. Springfield, NJ: Behrman House, Inc.

- ^ "David Nirenberg | Department of History | The University of Chicago". history.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory, Historiography, page 279 Chapter 13, The Rhineland Massacres of Jews in the First Crusade, Memories Medieval and Modern, by David Nirenberg

- ^ a b c T. A. Archer (1894). The Crusades: The Story Of The Latin Kingdom Of Jerusalem. G.P. Putnam Sons.

- ^ Jim Bradbury (2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 182.

- ^ Marvin Lowenthal, The Jews of Germany (1939)

- ^ Rubenstein, Jay, Armies of Heaven, ISBN 978 – 0 – 465 – 01929 – 8. page 51

- ^ P. Frankopan, The First Crusade: The Call from the East (London, 2012), p. 120.

- ^ CROSS PURPOSES: The Crusades (Transcript of Hoover Institute television show).

- ^ Gibb, H. A. R. The Damascus Chronicle of the Crusades: Extracted and Translated from the Chronicle of Ibn Al-Qalanisi. Dover Publications, 2003 (ISBN 0486425193), p.48

- ^ Rausch, David. Legacy of Hatred: Why Christians Must Not Forget the Holocaust. Baker Pub Group, 1990 (ISBN 0801077583), p.27

- ^ Goitein, S.D. A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. Vol. V: The Individual: Portrait of a Mediterranean Personality of the High Middle Ages as Reflected in the Cairo Geniza. University of California Press, 1988 (ISBN 0520056477), p.358

- ^ Kedar, Benjamin Z. "The Jerusalem Massacre of July 1099 in the Western Historiography of the Crusades." The Crusades. Vol. 3 (2004) (ISBN 075464099X), pp. 15–76, pg. 64

- ^ a b c Goitein, S.D. "Contemporary Letters on the Capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders." Journal of Jewish Studies 3 (1952), pp. 162–177, pg 163

- ^ Goitein, "Contemporary Letters on the Capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders," pg. 165

- ^ Goitein, "Contemporary Letters on the Capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders", p.166

- ^ http://catholiceducation.org/articles/history/world/wh0070.html

- ^ a b Stow, Kenneth (2007). Popes, Church, and Jews in the Middle Ages: Confrontation and Response. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754659150.

- ^ a b c Stow, Kenneth (1999). "The Church and the Jews". In Abulafia, David (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. 5. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521362894.012.

- ^ a b c Roth, Norman (1994). "Bishops and Jews in the Middle Ages". The Catholic Historical Review. 80 (1): 1–17. JSTOR 25024201.

- ^ Stacey, Robert C. "Crusades, Martyrdoms, and the Jews of Norman England, 1096–1190,"Juden Und Christen Der Zeit Der Kreuzzüge, edited by Alfred Haverkamp,p.233-51. Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 1999.

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1987). A History of the Crusades, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780521347709.

- ^ (German) Mentgen, Gerd (1996). "Die Juden des Mittelrhein-Mosel-Gebietes im Hochmittelalter unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Kreuzzugsverfolgungen". Der Erste Kreuzzug 1096 und Seine Folgen, die Verfolgung der Juden Im Rheinland. Evangelical Church in the Rhineland Schriften des Archivs der Evangelischen Kirche im Rheinland. 9.

- ^ Haverkamp, Eva (2009). "Martyrs in rivalry: the 1096 Jewish martyrs and the Thebean legion". Jewish History. 23 (4): 319–342. doi:10.1007/s10835-009-9091-1. JSTOR 25653802.

- ^ Chazan, Robert. God, Humanity, and History: The Hebrew First Crusade Narratives. (Berkeley; University of California Press, 2000), p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e Yuval, Israel. Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006. p. 140.

- ^ Hacker, Joseph (1966). "On the Persecutions of 1096". Zion. 31.

- ^ Althoff, Gerd; Fried, Johannes; Geary, Patrick J. (2002). Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory, Historiography. Cambridge UP. pp. 305–8. ISBN 9780521780667.

Bibliography[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

Manuscripts[edit]

- Albert of Aix, Historia Hierosolymitana

- Mainz Anonymous

- Solomon bar Simson Chronicle

- Eliezer bar Nathan Chronicle

Primary[edit]

- Charny, Israel W. (1994). The Widening Circle of Genocide. ISBN 978-1560001720.

- Chazan, Robert (1987). European Jewry and the First Crusade. University of California Press.

- Chazan, Robert (1996). In the Year 1096: The First Crusade and the Jews. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0827606326.

- Claster, Jill N. (2009). Sacred Violence: The European Crusades to the Middle East, 1095–1396. ISBN 978-1442600607.

- Cohen, Jeremy (2004). Sanctifying The Name of God: Jewish Martyrs and Jewish Memories of the First Crusade. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Eidelberg, Shlomo (1996). The Jews and the Crusaders. ISBN 978-0881255416.

- Hoffman, Lawrence A. (1989). Beyond the Text: A Holistic Approach to Liturgy. ISBN 978-0253205384.

- Nirenberg, David. "The Rhineland Massacres of Jews in the First Crusade, Memories Medieval and Modern*". Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory, Historiography.

- Reif, Stefan C. (1995). Judaism and Hebrew Prayer. ISBN 978-0521483414.

- Shwartz, Susan (2002). Cross and Crescent. ISBN 978-0759212923.

- Tartakoff, Paola (2012). Between Christian and Jew: Conversion and Inquisition in the Crown. ISBN 978-0812244212.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2009). The Crusades. ISBN 978-1402768910.

- Vauchez, André; Dobson, Richard Barrie; Lapidge, Michael (2000). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. 1. ISBN 978-1579582821.

Secondary sources[edit]

- (Hebrew) Yom Tov Assis; Geremi Cohen; Ora Limor; Aharon Kedar; Michael Toch, eds. (July 2000). Facing the Cross: The Persecutions of 1096 in History and Historiography. Jerusalem.

- Robert Chazan (2000). God, Humanity, and History: The Hebrew First-Crusade Narratives. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Chazan, Robert (1996). In the Year 1096: The Jews and the First Crusade. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America.

- Cohen, Jeremy. "A 1096 Complex? Constructing the First Crusade in Jewish Historical Memory, Medieval and Modern" (PDF).

- Cohen, Jeremy (13 Feb 2006). Sanctifying the Name of God: Jewish Martyrs and Jewish Memories of the First Crusade. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Nirenberg, David. The Rhineland Massacres of Jews in the First Crusade, Memories Medieval and Modern, in Medieval Concepts of the Past: Ritual, Memory. Historiography.

- Kedar, Benjamin Z. (1998). "Crusade Historians and the Massacres of 1096". Jewish History. 12 (2): 11–31. doi:10.1007/BF02335496. JSTOR 20101340.

- Otter, Monika (2012). Goscelin of St Bertin. ISBN 978-1843842941.

- Kenneth Setton, ed. (1969–1989). "A History of the Crusades". Madison.

- Vauchez, André; Dobson, Richard Barrie; Lapidge, Michael (2000). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. 1. ISBN 978-1579582821.

- Stow, Kenneth (2007). Popes, Church, and Jews in the Middle Ages: Confrontation and Response. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754659150.

- Roth, Norman (January 1994). "Bishops and Jews in the Middle Ages". The Catholic Historical Review. 80 (1): 1–17. JSTOR 25024201.

- Stow, Kenneth and David Abulafia (1999). "The Church and the Jews". Chapter 8: The Church and the Jews,The New Cambridge Medieval History,5:p.204–19. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 204–219. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521362894.012. ISBN 9781139055734.

- Stacey, Robert (1999). Chapter: Crusades, Martyrdoms, and the Jews of Norman England, 1096-1190, Juden Und Christen Der Zeit Der Kreuzzüge:p.233-251. Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag.

Journal articles[edit]

- Eidelberg, Shlomo (1999). "The First Crusade and the persecutions of 1096: a recollection for their 900th anniversary". Medieval Ashkenazic History.

- Eidelberg, Shlomo (1996). "The Jews and the Crusaders: The Hebrew Chronicles of the First and Second Crusades". History. KTAV Publishing House Inc. ISBN 9780881255416.

- Gabriele, Matthew (2007). Michael Frassetto (ed.). "Against the Enemies of Christ: The Role of Count Emicho in the Anti-Jewish Violence of the First Crusade". Christian Attitudes Towards the Jews in the Middle Ages. Routledge. ISBN 9780415978279.

- Goitein, G.D (1952). "Contemporary Letters on the Capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders". Journal of Jewish Studies. 3 (4): 162–177, 163. doi:10.18647/97/JJS-1952.

- (Hebrew) Hacker, Joseph (1966). "On the Persecutions of 1096". Zion. 31.

- (German) Haverkamp, Eva (2005). "Hebräische Berichte über die Judenverfolgungen während des Ersten Kreuzzugs [Hebrew reports on the persecution of Jews during the First Crusade]". Monumenta Germaniae Historica: Hebräische Texte aus dem Mittelalterlichen Deutschland. Hanover Hahnsche Buchhandlung. 1.

- Haverkamp, Eva (2008). "What did the Christians know? Latin reports on the persecutions of Jews in 1096". The Journal of the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East.

- Haverkamp, Eva (2009). "Martyrs in rivalry: the 1096 Jewish martyrs and the Thebean legion". Jewish History. 23 (4): 319–342. doi:10.1007/s10835-009-9091-1. JSTOR 25653802.

- Kober, Adolf (1940). "Cologne". Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America.

- Malkiel, David (2001). "Destruction or Conversion: Intention and Reaction, Crusaders and Jews, in 1096". Jewish History. 15 (3): 257–280. doi:10.1023/A:1014208904545. JSTOR 20101451.

- (German) Mentgen, Gerd. "Die Juden des Mittelrhein-Mosel-Gebietes im Hochmittelalter unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Kreuzzugsverfolgungen [The Jews of the Middle Rhine Moselle area in the High Middle Ages, with special emphasis on crusade persecutions]". Der Erste Kreuzzug 1096 und seine Folgen, die Verfolgung der Juden im Rheinland [The First Crusade in 1096 and its aftermath, the persecution of Jews in the Rhineland]. Evangelical Church in the Rhineland, Düsseldorf 1996 (Schriften des Archivs der Evangelischen Kirche im Rheinland. 9.

- "Die Juden des Mittelrhein-Mosel-Gebietes im Hochmittelalter unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Kreuzzugsverfolgungen [The Jews of the Middle Rhine Moselle area in the High Middle Ages, with special emphasis on crusade persecutions]". Monatshefte für Evangelische Kirchengeschichte des Rheinlandes. 44. 1995.

External links[edit]

- Albert of Aix and Ekkehard of Aura: Emico and the Slaughter of the Rhineland Jews.

- Jewish Encyclopedia: The Crusades

- Map and picture concerning German crusade

- Who Was Count Emicho? by Dr. Henry Abramson