Alkane

In organic chemistry, an alkane, or paraffin (a historical trivial name that also has other meanings), is an acyclic saturated hydrocarbon. In other words, an alkane consists of hydrogen and carbon atoms arranged in a tree structure in which all the carbon–carbon bonds are single.[1] Alkanes have the general chemical formula CnH2n+2. The alkanes range in complexity from the simplest case of methane (CH4), where n = 1 (sometimes called the parent molecule), to arbitrarily large and complex molecules, like pentacontane (C50H102) or 6-ethyl-2-methyl-5-(1-methylethyl) octane, an isomer of tetradecane (C14H30).

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines alkanes as "acyclic branched or unbranched hydrocarbons having the general formula CnH2n+2, and therefore consisting entirely of hydrogen atoms and saturated carbon atoms". However, some sources use the term to denote any saturated hydrocarbon, including those that are either monocyclic (i.e. the cycloalkanes) or polycyclic,[2] despite their having a distinct general formula (i.e. cycloalkanes are CnH2n).

In an alkane, each carbon atom is sp3-hybridized with 4 sigma bonds (either C–C or C–H), and each hydrogen atom is joined to one of the carbon atoms (in a C–H bond). The longest series of linked carbon atoms in a molecule is known as its carbon skeleton or carbon backbone. The number of carbon atoms may be considered as the size of the alkane.

One group of the higher alkanes are waxes, solids at standard ambient temperature and pressure (SATP), for which the number of carbon atoms in the carbon backbone is greater than about 17. With their repeated –CH2 units, the alkanes constitute a homologous series of organic compounds in which the members differ in molecular mass by multiples of 14.03 u (the total mass of each such methylene-bridge unit, which comprises a single carbon atom of mass 12.01 u and two hydrogen atoms of mass ~1.01 u each).

Methane is produced by methanogenic bacteria and some long-chain alkanes function as pheromones in certain animal species or as protective waxes in plants and fungi. Nevertheless, most alkanes do not have much biological activity. They can be viewed as molecular trees upon which can be hung the more active/reactive functional groups of biological molecules.

An alkyl group is an alkane-based molecular fragment that bears one open valence for bonding. They are generally abbreviated with the symbol for any organyl group, R, although Alk is sometimes used to specifically symbolize an alkyl group (as opposed to an alkenyl group or aryl group).

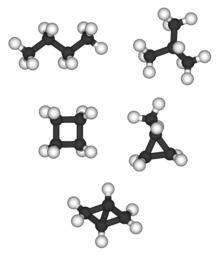

Bicyclo[1.1.0]butane is the only C4H6 alkane and has no alkane isomer; tetrahedrane (below) is the only C4H4 alkane and so has no alkane isomer.