| |

| |

| Nombres | |

|---|---|

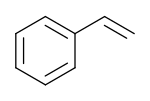

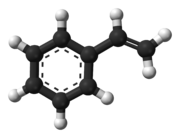

| Nombre IUPAC preferido Etenilbenceno [1] | |

| Otros nombres Estireno [1] Vinilbenceno Feniletileno Feniletileno Cinnamene Styrol Diarex HF 77 Styrolene Styropol | |

| Identificadores | |

Modelo 3D ( JSmol ) | |

| CHEBI | |

| CHEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Tarjeta de información ECHA | 100.002.592 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID | |

| Número RTECS |

|

| UNII | |

Tablero CompTox ( EPA ) | |

| |

| |

| Propiedades | |

| C 8 H 8 | |

| Masa molar | 104,15 g / mol |

| Apariencia | líquido aceitoso incoloro |

| Olor | dulce, floral [2] |

| Densidad | 0,909 g / cm 3 |

| Punto de fusion | −30 ° C (−22 ° F; 243 K) |

| Punto de ebullición | 145 ° C (293 ° F; 418 K) |

| 0,03% (20 ° C) [2] | |

| log P | 2,70 [3] |

| Presión de vapor | 5 mmHg (20 ° C) [2] |

| −6,82 × 10 −5 cm 3 / mol | |

Índice de refracción ( n D ) | 1.5469 |

| Viscosidad | 0,762 cP a 20 ° C |

| Estructura | |

| 0,13 D | |

| Peligros | |

| Principales peligros | inflamable, tóxico, probablemente cancerígeno |

| Ficha de datos de seguridad | MSDS |

| Frases R (desactualizadas) | R10 R36 |

| Frases S (desactualizadas) | S38 S20 S23 |

| NFPA 704 (diamante de fuego) |  2 3 2 |

| punto de inflamabilidad | 31 ° C (88 ° F; 304 K) |

| Límites explosivos | 0,9–6,8% [2] |

| Dosis o concentración letal (LD, LC): | |

LC 50 ( concentración media ) | 2194 ppm (ratón, 4 h ) 5543 ppm (rata, 4 h) [4] |

LC Lo ( más bajo publicado ) | 10,000 ppm (humano, 30 min) 2771 ppm (rata, 4 h) [4] |

| NIOSH (límites de exposición a la salud de EE. UU.): | |

PEL (permitido) | TWA 100 ppm C 200 ppm 600 ppm (pico máximo de 5 minutos en 3 horas cualesquiera) [2] |

REL (recomendado) | TWA 50 ppm (215 mg / m 3 ) ST 100 ppm (425 mg / m 3 ) [2] |

IDLH (peligro inmediato) | 700 ppm [2] |

| Compuestos relacionados | |

Estirenos relacionados; compuestos aromáticos relacionados | poliestireno , estilbeno ; etilbencina |

Salvo que se indique lo contrario, los datos se proporcionan para materiales en su estado estándar (a 25 ° C [77 ° F], 100 kPa). | |

| Referencias de Infobox | |

Estireno ( / s t aɪ r i n / ) [5] es un compuesto orgánico con la fórmula química C 6 H 5 CH = CH 2 . Este derivado de benceno es un aceitoso incoloro líquido , aunque muestras envejecidas pueden aparecer amarillento. El compuesto se evapora fácilmente y tiene un olor dulce, aunque las concentraciones altas tienen un olor menos agradable. El estireno es el precursor del poliestireno y varios copolímeros. En 2010 se produjeron aproximadamente 25 millones de toneladas de estireno [6]. aumentando a alrededor de 35 millones de toneladas para 2018.

Ocurrencia natural [ editar ]

El estireno lleva el nombre del bálsamo de estorax , la resina de los árboles Liquidambar de la familia de plantas Altingiaceae . El estireno se encuentra naturalmente en pequeñas cantidades en algunas plantas y alimentos ( canela , granos de café , árboles de bálsamo y maní ) [7] y también se encuentra en el alquitrán de hulla .

Historia [ editar ]

En 1839, el boticario alemán Eduard Simon aisló un líquido volátil de la resina (llamada estorax o styrax (latín)) del liquidámbar americano ( Liquidambar styraciflua ). Llamó al líquido "estirol" (ahora estireno). [8] [9] También notó que cuando el estirol se exponía al aire, la luz o el calor, se transformaba gradualmente en una sustancia dura parecida al caucho, a la que llamó "óxido de estirol". [10] En 1845, el químico alemán August Hofmann y su alumno John Blyth habían determinado la fórmula empírica del estireno : C 8 H 8 .[11] También habían determinado que el "óxido de estirol" de Simon, al que rebautizaron como "metastyrol", tenía la misma fórmula empírica que el estireno. [12] Además, podían obtener estireno destilando en seco "metastirol". [13] En 1865, el químico alemán Emil Erlenmeyer descubrió que el estireno podía formar un dímero , [14] y en 1866 el químico francés Marcelin Berthelot declaró que el "metastyrol" era un polímero de estireno (es decir, poliestireno ). [15] Mientras tanto, otros químicos habían estado investigando otro componente del estorax, a saber, el ácido cinámico.. Habían descubierto que el ácido cinámico podía descarboxilarse para formar "cinnamene" (o "cinnamol"), que parecía ser estireno. En 1845, el químico francés Emil Kopp sugirió que los dos compuestos eran idénticos, [16] y en 1866, Erlenmeyer sugirió que tanto el "cinnamol" como el estireno podrían ser vinilbenceno. [17] Sin embargo, el estireno que se obtenía del ácido cinámico parecía diferente del estireno que se obtenía al destilar la resina de estorax: este último era ópticamente activo . [18] Finalmente, en 1876, el químico holandés van 't HoffResolvió la ambigüedad: la actividad óptica del estireno que se obtenía al destilar la resina de estorax se debía a un contaminante. [19]

Producción industrial [ editar ]

De etilbenceno [ editar ]

La gran mayoría del estireno se produce a partir de etilbenceno , [20] y casi todo el etilbenceno producido en todo el mundo se destina a la producción de estireno. Como tal, los dos procesos de producción suelen estar muy integrados. El etilbenceno se produce mediante una reacción de Friedel-Crafts entre el benceno y el etileno ; originalmente, este utilizaba cloruro de aluminio como catalizador , pero en la producción moderna ha sido reemplazado por zeolitas .

Por deshidrogenación [ editar ]

Alrededor del 80% del estireno se produce por deshidrogenación de etilbenceno . Esto se logra utilizando vapor sobrecalentado (hasta 600 ° C) sobre un catalizador de óxido de hierro (III) . [21] La reacción es altamente endotérmica y reversible, con un rendimiento típico de 88 a 94%.

El producto de etilbenceno / estireno crudo se purifica luego por destilación. Como la diferencia en los puntos de ebullición entre los dos compuestos es de solo 9 ° C a presión ambiente, es necesario el uso de una serie de columnas de destilación. Esto consume mucha energía y se complica aún más por la tendencia del estireno a sufrir una polimerización inducida térmicamente en poliestireno, [22] requiriendo la adición continua de inhibidor de polimerización al sistema.

Vía hidroperóxido de etilbenceno [ editar ]

El estireno también se coproduce comercialmente en un proceso conocido como POSM ( Lyondell Chemical Company ) o SM / PO ( Shell ) para monómero de estireno / óxido de propileno . En este proceso, el etilbenceno se trata con oxígeno para formar el hidroperóxido de etilbenceno . Este hidroperóxido se usa luego para oxidar propileno a óxido de propileno, que también se recupera como coproducto. El 1-feniletanol restante se deshidrata para dar estireno:

Otras rutas industriales [ editar ]

Extracción de gasolina por pirólisis [ editar ]

La extracción de gasolina de pirólisis se realiza a una escala limitada. [20]

From toluene and methanol[edit]

Styrene can be produced from toluene and methanol, which are cheaper raw materials than those in the conventional process. This process has suffered from low selectivity associated with the competing decomposition of methanol.[23] Exelus Inc. claims to have developed this process with commercially viable selectivities, at 400–425 °C and atmospheric pressure, by forcing these components through a proprietary zeolitic catalyst. It is reported[24] that an approximately 9:1 mixture of styrene and ethylbenzene is obtained, with a total styrene yield of over 60%.[25]

From benzene and ethane[edit]

Another route to styrene involves the reaction of benzene and ethane. This process is being developed by Snamprogetti and Dow. Ethane, along with ethylbenzene, is fed to a dehydrogenation reactor with a catalyst capable of simultaneously producing styrene and ethylene. The dehydrogenation effluent is cooled and separated and the ethylene stream is recycled to the alkylation unit. The process attempts to overcome previous shortcomings in earlier attempts to develop production of styrene from ethane and benzene, such as inefficient recovery of aromatics, production of high levels of heavies and tars, and inefficient separation of hydrogen and ethane. Development of the process is ongoing.[26]

Laboratory synthesis[edit]

A laboratory synthesis of styrene entails the decarboxylation of cinnamic acid:[27]

- C6H5CH=CHCO2H → C6H5CH=CH2 + CO2

Styrene was first prepared by this method.[28]

Polymerization[edit]

The presence of the vinyl group allows styrene to polymerize. Commercially significant products include polystyrene, ABS, styrene-butadiene (SBR) rubber, styrene-butadiene latex, SIS (styrene-isoprene-styrene), S-EB-S (styrene-ethylene/butylene-styrene), styrene-divinylbenzene (S-DVB), styrene-acrylonitrile resin (SAN), and unsaturated polyesters used in resins and thermosetting compounds. These materials are used in rubber, plastic, insulation, fiberglass, pipes, automobile and boat parts, food containers, and carpet backing.

Hazards[edit]

Explosive autopolymerisation[edit]

As a liquid or a gas, pure styrene will polymerise spontaneously to polystyrene, without the need of external initiators.[29] This is known as autopolymerisation. At 100 °C it will autopolymerise at a rate of ~2% per hour, and more rapidly than this at higher temperatures.[22] The polymerisation reaction is exothermic; hence, there is a real risk of thermal runaway and explosion. An example is the 2019 explosion of the tanker Stolt Groenland; in this incident 5,250 metric tons of styrene monomer detonated while the ship was docked in Ulsan, Republic of Korea. The autopolymerisation reaction can only be kept in check by the continuous addition of polymerisation inhibitors.

Health effects[edit]

Styrene is regarded as a "known carcinogen", especially in case of eye contact, but also in case of skin contact, of ingestion and of inhalation, according to several sources.[20][30][31][32] Styrene is largely metabolized into styrene oxide in humans, resulting from oxidation by cytochrome P450. Styrene oxide is considered toxic, mutagenic, and possibly carcinogenic. Styrene oxide is subsequently hydrolyzed in vivo to styrene glycol by the enzyme epoxide hydrolase.[33] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has described styrene to be "a suspected toxin to the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, and respiratory system, among others".[34][35] On 10 June 2011, the U.S. National Toxicology Program has described styrene as "reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen".[36][37] However, a STATS author describes[38] a review that was done on scientific literature and concluded that "The available epidemiologic evidence does not support a causal relationship between styrene exposure and any type of human cancer".[39] Despite this claim, work has been done by Danish researchers to investigate the relationship between occupational exposure to styrene and cancer. They concluded, "The findings have to be interpreted with caution, due to the company based exposure assessment, but the possible association between exposures in the reinforced plastics industry, mainly styrene, and degenerative disorders of the nervous system and pancreatic cancer, deserves attention".[40] In 2012, the Danish EPA concluded that the styrene data do not support a cancer concern for styrene.[41] The U.S. EPA does not have a cancer classification for styrene,[42] but it has been the subject of their Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) program.[43] The National Toxicology Program of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has determined that styrene is "reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen".[44] Various regulatory bodies refer to styrene, in various contexts, as a possible or potential human carcinogen. The International Agency for Research on Cancer considers styrene to be "probably carcinogenic to humans".[45][46]

The neurotoxic[47] properties of styrene have also been studied and reported effects include effects on vision[48] (although unable to reproduce in a subsequent study[49]) and on hearing functions.[50][51][52][53] Studies on rats have yielded contradictory results,[51][52] but epidemiologic studies have observed a synergistic interaction with noise in causing hearing difficulties.[54][55][56]

Industrial accident[edit]

On 7 May 2020, a gas, reported to be styrene, leaked from a tank at the LG Chem (LG Polymers India Private Limited) plant at RR Venkatapuram, Visakhapatnam, Andra Pradesh, India. The leak occurred in the early morning hours while workers were preparing to reopen the plant, which was closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thirteen people reportedly died and over 200 people were hospitalized.[57][58]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. pp. P001–P004. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0571". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "Styrene". www.chemsrc.com.

- ^ a b "Styrene". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ "styrene". Oxford English and Spanish Dictionary, Thesaurus, and Spanish to English Translator. Lexico.com.

- ^ "New Process for Producing Styrene Cuts Costs, Saves Energy, and Reduces Greenhouse Gas Emissions" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2013.

- ^ Steele, D.H.; M.J., Thornburg; J.S., Stanley; R.R., Miller; R., Brooke; J.R., Cushman; G., Cruzan (1994). "Determination of styrene in selected foods". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 42 (8): 1661–1665. doi:10.1021/jf00044a015. ISSN 0021-8561. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018.

- ^ Simon, E. (1839) "Ueber den flüssigen Storax (Styrax liquidus)" (On liquid storax (Styrax liquidus), Annalen der Chemie, 31 : 265–277. From p. 268: "Das flüchtige Oel, für welches ich den Namen Styrol vorschlage, … " (The volatile oil, for which I suggest the name "styrol", … )

- ^ For further details of the history of styrene, see: F. W. Semmler, Die ätherischen Öle nach ihren chemischen Bestandteilen unter Berücksichtigung der geschichtlichen Entwicklung [The volatile liquids according to their chemical components with regard to historical development], vol. 4 (Leipzig, Germany, Veit & Co., 1907), § 327. Styrol, pp. 24-28. Archived 1 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (Simon, 1839), p. 268. From p. 268: "Für den festen Rückstand würde der Name Styroloxyd passen." (For the solid residue, the name "styrol oxide" would fit.)

- ^ See:

- Blyth, John; Hofmann, Aug. Wilhelm (1845a). "On styrole, and some of the products of its decomposition". Memoirs and Proceedings of the Chemical Society of London. 2: 334–358. doi:10.1039/mp8430200334. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018.; see p. 339.

- Reprinted in: Blyth, John; Hofmann, Aug. Wilhelm (August 1845b). "On styrole, and some of the products of its decomposition". Philosophical Magazine. 3rd series. 27 (178): 97–121. doi:10.1080/14786444508645234.; see p. 102.

- German translation: Blyth, John; Hofmann, Aug. Wilh. (1845c). "Ueber das Styrol und einige seiner Zersetzungsproducte" [On styrol and some of its decomposition products]. Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie (in German). 53 (3): 289–329. doi:10.1002/jlac.18450530302.; see p. 297.

- Note that Blyth and Hofmann state the empirical formula of styrene as C16H8 because at that time, some chemists used the wrong atomic mass for carbon (6 instead of 12).

- ^ (Blyth and Hofmann, 1845a), p. 348. From p. 348: "Analysis as well as synthesis has equally proved that styrol and the vitreous mass (for which we propose the name of metastyrol) possess the same constitution per cent."

- ^ (Blyth and Hofmann, 1845a), p. 350.

- ^ Erlenmeyer, Emil (1865) "Ueber Distyrol, ein neues Polymere des Styrols" (On distyrol, a new polymer of styrol), Annalen der Chemie, 135 : 122–123.

- ^ Berthelot, M. (1866) "Sur les caractères de la benzine et du styrolène, comparés avec ceux des autres carbures d'hydrogène" (On the characters of benzene and styrene, compared with those of other hydrocarbons), Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Paris, 2nd series, 6 : 289–298. From p. 294: "On sait que le styrolène chauffé en vase scellé à 200°, pendant quelques heures, se change en un polymère résineux (métastyrol), et que ce polymère, distillé brusquement, reproduit le styrolène." (One knows that styrene [when] heated in a sealed vessel at 200 °C, for several hours, is changed into a resinous polymer (metastyrol), and that this polymer, [when] distilled abruptly, reproduces styrene.)

- ^ Kopp, E. (1845), "Recherches sur l'acide cinnamique et sur le cinnamène" Archived 8 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Investigations of cinnamic acid and cinnamen), Comptes rendus, 21 : 1376–1380. From p. 1380: "Je pense qu'il faudra désormais remplacer le mot de styrol par celui de cinnamène, et le métastyrol par le métacinnamène." (I think that henceforth one will have to replace the word "styrol" with that of "cinnamène", and "metastyrol" with "metacinnamène".)

- ^ Erlenmeyer, Emil (1866) "Studien über die s.g. aromatischen Säuren" (Studies of the so-called aromatic acids), Annalen der Chemie, 137 : 327–359; see p. 353.

- ^ Berthelot, Marcellin (1867). "Sur les états isomériques du styrolène" [On the isomeric states of styrene]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 4th series (in French). 12: 159–161. From p. 160: "1° Le carbure des cinnamates est privé de pouvoir rotatoire, tandis que le carbure du styrax dévie de 3 degrés la teinte de passage (l = 100 mm)." (1. The carbon [atom] of cinnamates is bereft of rotary power [i.e., the ability to rotate polarized light], whereas the carbon of styrax deflects by 3 degrees the neutral tint [i.e., the relative orientation of the polarized quartz plates at which the light through the polarimeter appears colorless] (length = 100 mm). [For further details about 19th century polarimeters, see: Spottiswode, William (1883). Polarisation of Light (4th ed.). London: Macmillan and Co. pp. 51–52. Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2016.])

- ^ van 't Hoff, J. H. (1876) "Die Identität von Styrol und Cinnamol, ein neuer Körper aus Styrax" (The identity of styrol and cinnamol, a new substance from styrax), Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, 9 : 5-6.

- ^ a b c James, Denis H.; Castor, William M. (2007), "Styrene", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, p. 1, doi:10.1002/14356007.a25_329.pub2, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ Lee, Emerson H. (13 December 2006). "Iron Oxide Catalysts for Dehydrogenation of Ethylbenzene in the Presence of Steam". Catalysis Reviews. 8 (1): 285–305. doi:10.1080/01614947408071864.

- ^ a b Khuong, Kelli S.; Jones, Walter H.; Pryor, William A.; Houk, K.N. (February 2005). "The Mechanism of the Self-Initiated Thermal Polymerization of Styrene. Theoretical Solution of a Classic Problem". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (4): 1265–1277. doi:10.1021/ja0448667. PMID 15669866.

- ^ Yashima, Tatsuaki; Sato, Keiichi; Hayasaka, Tomoki; Hara, Nobuyoshi (1972). "Alkylation on synthetic zeolites: III. Alkylation of toluene with methanol and formaldehyde on alkali cation exchanged zeolites". Journal of Catalysis. 26 (3): 303–312. doi:10.1016/0021-9517(72)90088-7.

- ^ "Welcome to ICIS". www.icis.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Stephen K. Ritter, Chemical & Engineering News, 19 March 2007, p.46.

- ^ "CHEMSYSTEMS.COM" (PDF). www.chemsystems.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Abbott, T.W.; Johnson, J.R. (1941). "Phenylethylene (Styrene)". Organic Syntheses.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collective Volume, 1, p. 440

- ^ R. Fittig und F. Binder "Ueber die Additionsproducte der Zimmtssaure" in "Untersuchungen über die ungesättigten Säuren. I. Weitere Beiträge zur Kenntniß der Fumarsäure und Maleïnsäure" Rudolph Fittig, Camille Petri, Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1879, volume 195, pp. 56–179. doi:10.1002/jlac.18791950103

- ^ Miller, A.A.; Mayo, F.R. (March 1956). "Oxidation of Unsaturated Compounds. I. The Oxidation of Styrene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 78 (5): 1017–1023. doi:10.1021/ja01586a042.

- ^ MSDS (1 November 2010). "Material Safety Data Sheet Styrene (monomer) MSDS". MSDS. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "OPPT Chemical Fact Sheets (Styrene) Fact Sheet: Support Document (CAS No. 100-42-5)" (PDF). US EPA. December 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Liebman, Kenneth C. (1975). "Metabolism and toxicity of styrene" (PDF). Environmental Health Perspectives. 11: 115–119. doi:10.2307/3428333. JSTOR 3428333. PMC 1475194. PMID 809262.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "EPA settles case against Phoenix company for toxic chemical reporting violations". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ "EPA Fines California Hot Tub Manufacturer for Toxic Chemical Release Reporting Violations". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ Harris, Gardiner (10 June 2011). "Government Says 2 Common Materials Pose Risk of Cancer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ National Toxicology Program (10 June 2011). "12th Report on Carcinogens". National Toxicology Program. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Boffetta, P., et al., Epidemiologic Studies of Styrene and Cancer: A Review of the Literature Archived 9 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, J. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Nov.2009, V.51, N.11.

- ^ Kolstad, HA; Juel, K; Olsen, J; Lynge, E. (May 1995). "Exposure to styrene and chronic health effects: mortality and incidence of solid cancers in the Danish reinforced plastics industry". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 52 (5): 320–7. doi:10.1136/oem.52.5.320. PMC 1128224. PMID 7795754.

- ^ Danish EPA 2011 review "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) US environmental protection agency. Section I.B.4 relates to neurotoxicology.

- ^ "EPA IRIS track styrene page". epa.gov. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ "Styrene entry in National Toxicology Program's Thirteenth Report on Carcinogens" (PDF). nih.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ^ Kogevinas, Manolis; Gwinn, William M.; Kriebel, David; Phillips, David H.; Sim, Malcolm; Bertke, Stephen J.; Calaf, Gloria M.; Colosio, Claudio; Fritz, Jason M.; Fukushima, Shoji; Hemminki, Kari (2018). "Carcinogenicity of quinoline, styrene, and styrene-7,8-oxide". The Lancet Oncology. 19 (6): 728–729. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30316-4. ISSN 1470-2045. PMID 29680246.

- ^ "After 40 years in limbo: Styrene is probably carcinogenic". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Cherry, N.; Gautrin, D. (January 1990). "Neurotoxic effects of styrene: further evidence". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 47 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1136/oem.47.1.29. ISSN 0007-1072. PMC 1035091. PMID 2155647.

- ^ Murata, K.; Araki, S.; Yokoyama, K. (1991). "Assessment of the peripheral, central, and autonomic nervous system function in styrene workers". American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 20 (6): 775–784. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700200609. ISSN 0271-3586. PMID 1666820.

- ^ Seeber, Andreas; Bruckner, Thomas; Triebig, Gerhard (29 March 2009). "Occupational styrene exposure, colour vision and contrast sensitivity: a cohort study with repeated measurements". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. 82 (6): 757–770. doi:10.1007/s00420-009-0416-7. ISSN 0340-0131. PMID 19330514. S2CID 7463900.

- ^ Campo, Pierre; Venet, Thomas; Rumeau, Cécile; Thomas, Aurélie; Rieger, Benoît; Cour, Chantal; Cosnier, Frédéric; Parietti-Winkler, Cécile (October 2011). "Impact of noise or styrene exposure on the kinetics of presbycusis". Hearing Research. 280 (1–2): 122–132. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2011.04.016. ISSN 1878-5891. PMID 21616132. S2CID 34799773.

- ^ a b Lataye, R.; Campo, P.; Loquet, G.; Morel, G. (April 2005). "Combined effects of noise and styrene on hearing: comparison between active and sedentary rats". Noise & Health. 7 (27): 49–64. doi:10.4103/1463-1741.31633. ISSN 1463-1741. PMID 16105249.

- ^ a b Campo, Pierre; Venet, Thomas; Thomas, Aurélie; Cour, Chantal; Brochard, Céline; Cosnier, Frédéric (July 2014). "Neuropharmacological and cochleotoxic effects of styrene. Consequences on noise exposures". Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 44: 113–120. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2014.05.009. ISSN 1872-9738. PMID 24929234.

- ^ Johnson, Ann-Christin (2010) [2009]. Occupational exposure to chemicals and hearing impairment. Morata, Thais C., Nordic Expert Group for Criteria Documentation of Health Risks from Chemicals., Sahlgrenska akademin (Göteborgs universitet), Göteborgs universitet., Arbetsmiljöverket. Gotenburg: University of Gothenburg. ISBN 9789185971213. OCLC 792746283.

- ^ Sliwińska-Kowalska, Mariola; Zamyslowska-Szmytke, Ewa; Szymczak, Wieslaw; Kotylo, Piotr; Fiszer, Marta; Wesolowski, Wiktor; Pawlaczyk-Luszczynska, Malgorzata (January 2003). "Ototoxic effects of occupational exposure to styrene and co-exposure to styrene and noise". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 45 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1097/00043764-200301000-00008. ISSN 1076-2752. PMID 12553175. S2CID 7030810.

- ^ Morata, Thais C.; Sliwinska-Kowalska, Mariola; Johnson, Ann-Christin; Starck, Jukka; Pawlas, Krystyna; Zamyslowska-Szmytke, Ewa; Nylen, Per; Toppila, Esko; Krieg, Edward (October 2011). "A multicenter study on the audiometric findings of styrene-exposed workers". International Journal of Audiology. 50 (10): 652–660. doi:10.3109/14992027.2011.588965. ISSN 1708-8186. PMID 21812635. S2CID 207571026.

- ^ Sisto, R.; Cerini, L.; Gatto, M.P.; Gherardi, M.; Gordiani, A.; Sanjust, F.; Paci, E.; Tranfo, G.; Moleti, A. (November 2013). "Otoacoustic emission sensitivity to exposure to styrene and noise". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 134 (5): 3739–3748. Bibcode:2013ASAJ..134.3739S. doi:10.1121/1.4824618. ISSN 1520-8524. PMID 24180784.

- ^ "Vizag Gas Leak Live News: Eleven dead, several hospitalised after toxic gas leak from LG Polymers plant". The Economic Times. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Hundreds in hospital after leak at Indian chemical factory closed by lockdown". The Guardian. 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

External links[edit]

- American Industrial Hygiene Association, The Ear Poisons, The Synergist, November 2018.

- CDC – Styrene – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

- Safety and Health Topics | Styrene (OSHA)

- Nordic Expert Group, Occupational Exposure to Chemicals and Hearing Impairment, 2010.

- OSHA-NIOSH 2018. Preventing Hearing Loss Caused by Chemical (Ototoxicity) and Noise Exposure Safety and Health Information Bulletin (SHIB), Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. SHIB 03-08-2018. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2018-124.