| La pasión de Cristo | |

|---|---|

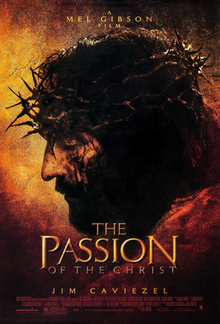

Cartel de estreno teatral. | |

| Dirigido por | Mel Gibson |

| Producido por |

|

| Guión por |

|

| Residencia en | La Pasión en el Nuevo Testamento de la Biblia y La Dolorosa Pasión de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo por Anne Catherine Emmerich |

| Protagonizada | |

| Musica por | John Debney |

| Cinematografía | Caleb Deschanel |

| Editado por |

|

| Empresa de producción | |

| Distribuido por | Producciones Icon |

| Fecha de lanzamiento |

|

| Tiempo de ejecución | 127 minutos [1] |

| País | Estados Unidos |

| Idiomas | |

| Presupuesto | $ 30 millones [2] |

| Taquilla | $ 612 millones [2] |

La Pasión de Cristo [3] es una película dramática bíblica estadounidense de 2004producida, coescrita y dirigida por Mel Gibson y protagonizada por Jim Caviezel como Jesús de Nazaret , Maia Morgenstern como la Virgen María y Monica Bellucci como María Magdalena . Representa la Pasión de Jesús en gran parte de acuerdo con los evangelios de Mateo , Marcos , Lucas y Juan . También se basa en relatos piadosos como el Viernes de Dolores., junto con otros escritos devocionales, como las supuestas visiones atribuidas a Anne Catherine Emmerich . [4] [5] [6] [7]

La película cubre principalmente las últimas 12 horas antes de la muerte de Jesucristo, que consisten en la Pasión, de ahí el título de la película. Comienza con la Agonía en el Huerto del Huerto de los Olivos (o Getsemaní), continúa con la traición de Judas Iscariote , la flagelación brutal en el Pilar , el sufrimiento de María profetizado por Simeón y la crucifixión y muerte de Jesús. y termina con una breve descripción de su resurrección . Sin embargo, la película también tiene flashbacks de momentos particulares en la vida de Jesús, algunos de los cuales están basados en la Biblia, como La Última Cena y El Sermón del Monte., y otras que son de licencia artística, como cuando María consuela a Jesús y cuando Jesús hace una mesa.

La película se rodó principalmente en Italia . [8] El diálogo está íntegramente en hebreo, latín y arameo reconstruido . Aunque Gibson inicialmente estaba en contra, la película está subtitulada.

La película ha sido controvertida y recibió críticas en gran medida polarizadas, con algunos críticos calificando la película de un clásico religioso, mientras que otros encontraron la violencia extrema distractora y excesiva. La película recaudó más de $ 612 millones en todo el mundo [9] y se convirtió en la séptima película más taquillera a nivel nacional al final de su carrera teatral. [2] Es la película cristiana más taquillera (sin ajustar la inflación) de todos los tiempos. [10] Recibió tres nominaciones en la 77ª edición de los Premios de la Academia en 2005, por Mejor maquillaje , Mejor fotografía y Mejor banda sonora original . [11]

Trama [ editar ]

En las últimas horas de la noche en el huerto boscoso de Getsemaní, Jesús ora mientras sus discípulos San Pedro , Santiago y Juan, los hijos de Zebedeo, duermen. Mientras ora en reclusión, Satanás se le aparece a Jesús en forma andrógina y lo tienta diciéndole que nadie puede soportar la carga que Dios le pide: sufrir y morir por los pecados de la humanidad. El sudor de Jesús se convierte en sangre y gotea al suelo mientras una serpiente emerge del disfraz de Satanás. Jesús escucha a sus discípulos llamarlo y reprende a Satanás aplastando la cabeza de la serpiente.

Judas Iscariote, otro de los discípulos de Jesús, habiendo recibido un soborno de 30 piezas de plata, conduce a un grupo de guardias del templo al bosque y traiciona la identidad de Jesús. Cuando los guardias arrestan a Jesús, estalla una pelea en la que Pedro saca su daga y corta la oreja de Malco, uno de los guardias y sirviente del sumo sacerdote Caifás. Jesús sana la herida de Malco mientras regaña a Pedro. Mientras los discípulos huyen, los guardias aseguran a Jesús y lo golpean durante el viaje al Sanedrín.

Juan informa a María, la madre de Jesús, y a María Magdalena del arresto, mientras que Pedro sigue a Jesús y sus captores. Magdalena le ruega a una patrulla romana que intervenga, pero un guardia del templo les asegura que está loca. Caifás lleva a cabo un juicio por la objeción de algunos de los otros sacerdotes, que son expulsados de la corte. Se presentan contra él falsas acusaciones y testigos. Cuando Caifás le pregunta si es el Hijo de Dios, Jesús responde "Yo soy". Caifás rasga sus vestiduras indignado y Jesús es condenado a muerte por blasfemia. Pedro se enfrenta a la multitud que lo rodea por ser un seguidor de Jesús. Después de maldecir a la turba durante la tercera negación, Pedro huye cuando recuerda la advertencia de Jesús sobre su defensa. Un Judas lleno de culpa intenta devolver el dinero que le pagaron para liberar a Jesús, pero los sacerdotes lo rechazan.Judas se aísla y un grupo de niños comienzan a atormentarlo y le revelan que son demonios. Judas, lleno de dolor, huye de la ciudad y se ahorca con una cuerda que le quitó a un burro muerto.

Caifás lleva a Jesús ante Poncio Pilato para que sea condenado a muerte. A instancias de su esposa Claudia, que conoce la condición de Jesús como hombre de Dios, y después de interrogar a Jesús y no encontrar ninguna falta, Pilato lo transfiere a la corte de Herodes Antipas (ya que Jesús es de Nazaret , dentro de la jurisdicción de Antipas de Antipas). Galilea ). Después de que Jesús es ridiculizado en la corte de Herodes y regresa, Pilato ofrece a la multitud la opción de castigar a Jesús o soltarlo. Intenta que Jesús sea liberado por la elección de la gente entre Jesús y el criminal violento Barrabás . La multitud exige que se libere a Barrabás y que se crucifique a Jesús. Intentando apaciguar a la multitud, Pilato ordena que se azote severamente a Jesús. Jesús es luego azotado, abusado y burladopor los guardias romanos. Lo llevan a un granero donde le colocan una corona de espinas en la cabeza y se burlan de él diciendo "Salve, rey de los judíos". Un Jesús sangrante se presenta ante Pilato, pero Caifás, con el ánimo de la multitud, sigue exigiendo que Jesús sea crucificado. Pilato se lava las manos del asunto y, a regañadientes, ordena la crucifixión de Jesús. Satanás observa el sufrimiento de Jesús con placer sádico.

Mientras Jesús lleva una pesada cruz de madera a lo largo de la Vía Dolorosa hasta el Calvario, Santa Verónica, una mujer, evita la escolta de los soldados y le pide a Jesús que le limpie la cara con su paño , a lo que él consiente. Le ofrece a Jesús una olla de agua para beber, pero el guardia la tira y la disipa. Durante el viaje al Gólgota, los guardias golpean a Jesús hasta que el involuntario Simón de Cirene se ve obligado a llevar la cruz con él. Al final de su viaje, con su madre María, María Magdalena y otros testigos, Jesús es crucificado.

Colgado de la cruz, Jesús ora a Dios Padre pidiendo perdón por las personas que lo atormentaban, y brinda salvación a un ladrón penitente crucificado a su lado. Jesús entrega su espíritu al Padre y muere. Una sola gota de lluvia cae del cielo al suelo, provocando un terremoto que destruye el templo y rasga el velo que cubre el Lugar Santísimo en dos. Satanás grita derrotado desde las profundidades del infierno. El cuerpo de Jesús es bajado de la cruz y sepultado. Jesús se levanta de entre los muertos y sale de la tumba resucitado, con los agujeros de las heridas visibles en sus palmas.

Transmitir [ editar ]

- Jim Caviezel como Jesús de Nazaret

- Maia Morgenstern como María, la madre de Jesús

- Christo Jivkov como John

- Francesco De Vito como Peter

- Monica Bellucci como María Magdalena

- Mattia Sbragia como Caifás

- Toni Bertorelli como Annas ben Seth

- Luca Lionello como Judas Iscariote

- Hristo Naumov Shopov como Poncio Pilato

- Claudia Gerini como Claudia Procles

- Fabio Sartor como Abenader

- Giacinto Ferro como José de Arimatea

- Olek Mincer como Nicodemus

- Sheila Mokhtari como mujer en audiencia

- Sergio Rubini como Dismas

- Roberto Bestazoni como Malchus

- Francesco Cabras como Gesmas

- Giovanni Capalbo como Cassius

- Rosalinda Celentano como Satan

- Emilio De Marchi como Román desdeñoso

- Lello Giulivo como Brutish Roman

- Abel Jafry como oficial del segundo templo

- Jarreth Merz como Simón de Cirene

- Matt Patresi como Janus

- Roberto Visconti como Román desdeñoso

- Luca De Dominicis como Herodes Ántipas

- Chokri Ben Zagden como James

- Sabrina Impacciatore como Santa Verónica

- Pietro Sarubbi como Barrabás

- Ted Rusoff como Chief Elder

Temas [ editar ]

En La Pasión: Fotografía de la película "La Pasión de Cristo" , el director Mel Gibson dice: "Esta es una película sobre el amor, la esperanza, la fe y el perdón. Jesús murió por toda la humanidad, sufrió por todos nosotros. Es hora de regrese al mensaje básico. El mundo se ha vuelto loco. A todos nos vendría bien un poco más de Amor, Fe, Esperanza y perdón ".

Material de origen [ editar ]

Nuevo Testamento [ editar ]

Según Mel Gibson, la fuente principal de material de La Pasión de Cristo son las cuatro narraciones canónicas del Evangelio de la pasión de Cristo . La película incluye un juicio de Jesús en la corte de Herodes , que solo se encuentra en el Evangelio de Lucas . Muchas de las declaraciones de Jesús en la película no pueden derivarse directamente del Evangelio y son parte de una narrativa cristiana más amplia. La película también se basa en otras partes del Nuevo Testamento . Una línea que dijo Jesús en la película, "Yo hago nuevas todas las cosas", se encuentra en el Libro de Apocalipsis , Capítulo 21, versículo 5. [12]

Antiguo Testamento [ editar ]

La película también se refiere al Antiguo Testamento . La película comienza con un epígrafe del cuarto cántico del siervo sufriente de Isaías . [13] En la escena inicial ambientada en el Huerto de Getsemaní , Jesús aplasta la cabeza de una serpiente en alusión visual directa a Génesis 3:15 . [14] A lo largo de la película, Jesús cita los Salmos , más allá de los casos registrados en el Nuevo Testamento .

Iconografía e historias tradicionales [ editar ]

Muchas de las representaciones de la película reflejan deliberadamente las representaciones tradicionales de la Pasión en el arte. Por ejemplo, las 14 Estaciones de la Cruz son fundamentales para la representación de la Vía Dolorosa en La Pasión de Cristo. Todas las estaciones están representadas excepto la octava estación (Jesús se encuentra con las mujeres de Jerusalén, una escena eliminada en el DVD) y la decimocuarta estación (Jesús está en la tumba). Gibson se inspiró en la representación de Jesús en la Sábana Santa de Turín . [15]

Por sugerencia de la actriz Maia Morgenstern , el Seder de Pascua se cita al principio de la película. María pregunta "¿Por qué esta noche es diferente a otras noches?", Y María Magdalena responde con la respuesta tradicional: "Porque una vez fuimos esclavos, y ya no somos esclavos". [dieciséis]

La fusión de María Magdalena con la adúltera salvada de la lapidación por Jesús tiene algún precedente en la tradición, y según el director se hizo por motivos dramáticos. Los nombres de algunos personajes de la película son tradicionales y extra-bíblicos, como los ladrones crucificados junto al Cristo, Dismas y Gesmas (también Gestas ).

Escritos devocionales católicos [ editar ]

Los guionistas Gibson y Benedict Fitzgerald dijeron que leyeron muchos relatos de la Pasión de Cristo en busca de inspiración, incluidos los escritos devocionales de los místicos católicos romanos. Una fuente principal es La Dolorosa Pasión de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo [17], las visiones de Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774-1824), escritas por el poeta Clemens Brentano . [5] [6] [7] Una lectura cuidadosa del libro de Emmerich muestra el alto nivel de dependencia de la película. [5] [6] [18]

Sin embargo, la atribución de Brentano del libro La Dolorosa Pasión de Nuestro Señor Jesucristo a Emmerich ha sido objeto de disputa, con acusaciones de que Brentano escribió gran parte del libro él mismo; una investigación del Vaticano que concluye que: "No es absolutamente seguro que alguna vez haya escrito esto". [19] [20] [21] En su reseña de la película en la publicación católica America , el sacerdote jesuita John O'Malley usó los términos "ficción devota" y "fraude bien intencionado" para referirse a los escritos de Clemens Brentano. [4] [19]

Producción [ editar ]

Guión e idioma [ editar ]

Gibson anunció originalmente que usaría dos idiomas antiguos sin subtítulos y que se basaría en la "narración cinematográfica". Debido a que la historia de la Pasión es tan conocida, Gibson sintió la necesidad de evitar las lenguas vernáculas para sorprender al público: "Creo que es casi contraproducente decir algunas de estas cosas en un idioma moderno. Te dan ganas de ponerte de pie y grita la siguiente línea, como cuando escuchas 'Ser o no ser' e instintivamente te dices a ti mismo: 'Esa es la pregunta' ". [22] El guión fue escrito en inglés por Gibson y Benedict Fitzgerald , luego traducido por William Fulco, SJ, profesor de la Universidad Loyola Marymount, en latín y arameo reconstruido. Gibson eligió usar el latín en lugar del griego koiné , que era la lengua franca de esa parte particular del Imperio Romano en ese momento, ya que no hay una fuente para el griego koiné que se habla en esa región. El griego de la calle que se hablaba en la antigua región del Levante de la época de Jesús no es el idioma griego exacto que se usa en la Biblia. [23] Fulco a veces incorporó errores deliberados en las pronunciaciones y terminaciones de palabras cuando los personajes hablaban un idioma desconocido para ellos, y parte del lenguaje tosco utilizado por los soldados romanos no se traducía en los subtítulos. [24]

Filmando [ editar ]

La película se produjo de forma independiente y se rodó en Italia en Cinecittà Studios en Roma, y en locaciones de la ciudad de Matera y la ciudad fantasma de Craco , ambas en la región de Basilicata . El costo de producción estimado de US $ 30 millones, más un estimado adicional de $ 15 millones en costos de marketing, fueron asumidos íntegramente por Gibson y su compañía Icon Productions . Según el artículo especial del DVD, Martin Scorsese acababa de terminar su película Gangs of New York , a partir de la cual Gibson y sus diseñadores de producción construyeron parte de su set utilizando el set de Scorsese. Esto le ahorró a Gibson mucho tiempo y dinero.

La película de Gibson se estrenó el miércoles de ceniza , 25 de febrero de 2004. Icon Entertainment distribuyó la versión teatral de la película y 20th Century Fox distribuyó la versión VHS / DVD / Blu-ray de la película.

Gibson consultó a varios asesores teológicos durante el rodaje, incluido el p. Jonathan Morris . Un sacerdote local visitó el set todos los días para brindar consejo, confesión y la sagrada comunión a Jim Caviezel , y se celebraron misas para el elenco y el equipo en varios lugares. [25] Durante el rodaje, el director asistente Jan Michelini fue alcanzado dos veces por un rayo. Minutos después, Caviezel también fue golpeado. [26] [27] [28]

Música [ editar ]

Se lanzaron tres álbumes con la cooperación de Mel Gibson : (1) la banda sonora de la película de la partitura orquestal original de John Debney dirigida por Nick Ingman ; (2) La Pasión de Cristo: Canciones , de los productores Mark Joseph y Tim Cook, con composiciones originales de varios artistas, y (3) Canciones inspiradas en La Pasión de Cristo . Los dos primeros álbumes recibieron cada uno un premio Dove en 2005 , y la banda sonora recibió una nominación al Premio de la Academia de Mejor Banda Sonora Original .

Una partitura preliminar fue compuesta y grabada por Lisa Gerrard y Patrick Cassidy , pero estaba incompleta en el lanzamiento de la película. Jack Lenz fue el investigador musical principal y uno de los compositores; [29] Se han publicado en línea varios clips de sus composiciones. [30]

Cambio de título [ editar ]

Aunque Mel Gibson quiso llamar a su película La Pasión , el 16 de octubre de 2003 su portavoz anunció que el título utilizado en Estados Unidos sería La Pasión de Cristo porque Miramax Films ya había registrado el título La Pasión en la MPAA para 1987. novela de Jeanette Winterson . [31] Posteriormente, el título se cambió nuevamente a La Pasión de Cristo para todos los mercados.

Distribución y marketing [ editar ]

Gibson comenzó la producción de su película sin obtener financiación ni distribución externas. En 2002, explicó por qué no podía conseguir el respaldo de los estudios de Hollywood: "Esta es una película sobre algo que nadie quiere tocar, rodada en dos idiomas muertos". [32] Gibson y su compañía Icon Productions proporcionaron el respaldo exclusivo de la película, gastando alrededor de $ 30 millones en costos de producción y un estimado de $ 15 millones en marketing. [33] Después de las primeras acusaciones de antisemitismo, Gibson tuvo dificultades para encontrar una empresa de distribución estadounidense. 20th Century Fox inicialmente tenía un acuerdo de primera vista con Icon, pero decidió pasar la película en respuesta a las protestas públicas. [34]Para evitar el espectáculo de otros estudios que rechazaban la película y para evitar someter a la distribuidora a la misma intensa crítica pública que había recibido, Gibson decidió distribuir la película él mismo en Estados Unidos, con la ayuda de Newmarket Films . [35]

Gibson se apartó de la fórmula habitual de marketing cinematográfico. Empleó una campaña publicitaria de televisión a pequeña escala sin reuniones de prensa. [36] Similar a las campañas de marketing de películas bíblicas anteriores como El Rey de Reyes , La Pasión de Cristo fue fuertemente promovida por muchos grupos eclesiásticos, tanto dentro de sus organizaciones como entre el público. La mercancía con licencia típica como carteles, camisetas, tazas de café y joyas se vendía a través de minoristas y sitios web. [37] La Iglesia Metodista Unida declaró que muchos de sus miembros, al igual que otros cristianos, sintieron que la película era una buena manera de evangelizar a los no creyentes. [38]Como resultado, muchas congregaciones planearon estar en los teatros y algunas instalaron mesas para responder preguntas y compartir oraciones. [38] El reverendo John Tanner, pastor de la Iglesia Metodista Unida de Cove en Hampton Cove, Alabama, dijo: "Sienten que la película presenta una oportunidad única para compartir el cristianismo de una manera con la que el público de hoy puede identificarse". [38] La Iglesia Adventista del Séptimo Día también expresó un respaldo similar a la imagen. [39]

Apoyo evangélico [ editar ]

La Pasión de Cristo recibió el apoyo entusiasta de la comunidad evangélica estadounidense . [40] Antes del estreno de la película, Gibson se acercó activamente a los líderes evangélicos en busca de su apoyo y comentarios. [41] Con su ayuda, Gibson organizó y asistió a una serie de proyecciones previas al lanzamiento para audiencias evangélicas y discutió la realización de la película y su fe personal. En junio de 2003, proyectó la película para 800 pastores que asistían a una conferencia de liderazgo en la Iglesia New Life , pastoreada por Ted Haggard , entonces presidente de la Asociación Nacional de Evangélicos . [42] Gibson ofreció proyecciones similares en Joel Osteen.Es la Iglesia Lakewood , Greg Laurie 's Harvest Christian Fellowship , y a 3.600 pastores en una conferencia en Rick Warren 's Iglesia Saddleback en Lake Forest. [43] Desde el verano de 2003 hasta el estreno de la película en febrero de 2004, se mostraron partes o cortes preliminares de la película a más de ochenta audiencias, muchas de las cuales eran audiencias evangélicas. [44] La película también recibió el respaldo público de líderes evangélicos, incluidos Rick Warren , Billy Graham , Robert Schuller , Darrell Bock , el editor de Christianity Today , David Neff,Pat Robertson , Lee Strobel , Jerry Falwell , Max Lucado , Tim LaHaye y Chuck Colson . [44] [45]

Liberar [ editar ]

Taquilla y carrera teatral [ editar ]

La Pasión de Cristo se inauguró en Estados Unidos el 25 de febrero de 2004 ( Miércoles de Ceniza , inicio de la Cuaresma ). Ganó $ 83,848,082 de 4,793 pantallas en 3,043 cines en su fin de semana de apertura y un total de $ 125,185,971 desde su apertura del miércoles, ubicándose en el cuarto lugar general en ganancias domésticas del fin de semana de apertura para 2004, así como el mayor debut de fin de semana para un estreno en febrero (hasta Fifty Shades of Gray fue liberado). Continuó ganando $ 370,782,930 en general en los Estados Unidos, [2] y sigue siendo la película con clasificación R más taquillera en el mercado nacional (EE. UU. Y Canadá). [46] [47] [48] [49] [50]La película vendió un estimado de 59,625,500 boletos en los EE. UU. En su presentación teatral inicial. [51]

En Filipinas, un país de mayoría católica, la película se estrenó el 31 de marzo de 2004, [52] [53] clasificada PG-13 por la Junta de Clasificación y Revisión de Cine y Televisión (MTRCB) [54] y respaldada por la Asociación Católica. Conferencia Episcopal de Filipinas (CBCP). [55]

En Malasia , los censores del gobierno inicialmente la prohibieron por completo, pero después de que los líderes cristianos protestaron, se levantó la restricción, pero solo para el público cristiano, lo que les permitió ver la película en cines especialmente designados. [56] En Israel, la película no fue prohibida. Sin embargo, nunca recibió distribución teatral porque ningún distribuidor israelí lo comercializaría. [57]

A pesar de las muchas controversias y negativas de algunos gobiernos para permitir que la película se vea en un amplio estreno, La Pasión de Cristo ganó $ 612,054,428 en todo el mundo. [2] La película también fue un éxito relativo en ciertos países con grandes poblaciones musulmanas, [58] como en Egipto, donde ocupó el puesto 20 en general en sus cifras de taquilla para 2004. [59] La película fue la más taquillera no Película en inglés de todos los tiempos [60] hasta 2017, cuando fue superada por Wolf Warrior 2 . [61]

Estreno en cines reeditado el 11 de marzo de 2005 [ editar ]

The Passion Recut se estrenó en los cines el 11 de marzo de 2005, con cinco minutos de la violencia más explícita eliminados. Gibson explicó su razonamiento para esta versión reeditada:

Después de la presentación inicial en los cines, recibí numerosas cartas de personas de todo el país. Muchos me dijeron que querían compartir la experiencia con sus seres queridos, pero les preocupaba que las imágenes más duras de la película fueran demasiado intensas para que las soportaran. A la luz de esto, decidí reeditar La Pasión de Cristo . [62]

A pesar de la reedición, la Motion Picture Association of America todavía consideró que The Passion Recut era demasiado violento para PG-13 , por lo que su distribuidor lo publicó como no calificado. [62] La película abreviada se mostró durante tres semanas en 960 cines por un total de taquilla de $ 567,692, minúsculo en comparación con los $ 612,054,428 de La Pasión . [63]

Medios domésticos [ editar ]

El 31 de agosto de 2004, la película fue lanzada en VHS y DVD en Norteamérica por 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, que inicialmente pasó a la distribución en cines. [ cita requerida ] Al igual que con el estreno en cines original, el lanzamiento de la película en formatos de video casero resultó ser muy popular. Las primeras estimaciones indicaron que más de 2,4 millones de copias de la película se vendieron a las 3 pm, [64] con un total de 4,1 millones de copias en su primer día de venta. [65] La película estaba disponible en DVD con subtítulos en inglés y español y en cinta VHS con subtítulos en inglés. La película fue lanzada en Blu-ray en Norteamérica como una Edición Definitiva de dos discos el 17 de febrero de 2009. [66] También se lanzó en Blu-ray en Australia una semana antes de Pascua.

Aunque el lanzamiento del DVD original se vendió bien, no contenía más características adicionales que un avance, lo que provocó especulaciones sobre cuántos compradores esperarían a que se lanzara una edición especial . [64] El 30 de enero de 2007, se lanzó una Edición Definitiva de dos discos en los mercados de América del Norte y el 26 de marzo en otros lugares. Contiene varios documentales, comentarios de bandas sonoras , escenas eliminadas , tomas descartadas , la versión sin clasificación de 2005 y la versión teatral original de 2004.

La versión británica del DVD de dos discos contiene dos escenas eliminadas adicionales. En el primero, Jesús se encuentra con las mujeres de Jerusalén (en la octava estación de la cruz) y cae al suelo mientras las mujeres se lamentan a su alrededor, y Simón de Cirene.intenta sostener la cruz y ayudar a Jesús simultáneamente. Después, mientras ambos sostienen la cruz, Jesús dice a las mujeres que lloran por él: "No lloréis por mí, sino por vosotros y por vuestros hijos". En el segundo, Pilato se lava las manos, se vuelve hacia Caifás y dice: "Míralo" (es decir, los fariseos desean que crucifiquen a Jesús). Pilato luego se vuelve hacia Abanader y le dice: "Haz lo que quieran". La escena siguiente muestra a Pilato llamando a su criado, que lleva una tabla de madera en la que Pilato escribe, "Jesús de Nazaret, el Rey de los judíos", en latín y hebreo. Luego sostiene la tabla sobre su cabeza a la vista de Caifás, quien después de leerla desafía a Pilato sobre su contenido. Pilato responde airadamente a Caifás en hebreo sin subtítulos. El disco contiene solo dos escenas eliminadas en total.No se muestran otras escenas de la película en el disco 2.[67]

El 7 de febrero de 2017, 20th Century Fox relanzó la película en Blu-ray y DVD con ambos cortes, con la versión teatral doblada en inglés y español; [68] Esta es la primera vez que la película se dobla a otro idioma.

Transmisión de televisión [ editar ]

El 17 de abril de 2011 ( Domingo de Ramos ), Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) presentó la película a las 7:30 pm ET / PT, con múltiples proyecciones programadas. La cadena ha continuado transmitiendo la película durante todo el año, y particularmente en Semana Santa. [69]

El 29 de marzo de 2013 ( Viernes Santo ), como parte de su programación especial de Semana Santa , TV5 presentó la versión doblada en filipino de la película a las 2:00 pm ( PST , UTC + 8 ) en Filipinas. Su transmisión total duró dos horas, pero excluyendo los anuncios, solo duraría aproximadamente una hora en lugar de su tiempo de ejecución completo de dos horas y seis minutos. Terminó a las 4:00 pm. Ha sido calificado como SPG por la Junta de Clasificación y Revisión de Películas y Televisión.(MTRCB) por temas, lenguaje y violencia con algunas escenas censuradas para televisión. TV5 es la primera red de transmisión fuera de los Estados Unidos y apodó el hebreo vernáculo y el latín al filipino (mediante la traducción de los subtítulos en inglés suministrados).

Recepción [ editar ]

Respuesta crítica [ editar ]

En Rotten Tomatoes , la película tiene una calificación de aprobación del 49% según 278 reseñas, con una calificación promedio de 5.91 / 10. El consenso crítico del sitio web dice: "El celo del director Mel Gibson es inconfundible, pero La Pasión de Cristo dejará a muchos espectadores emocionalmente agotados en lugar de elevados espiritualmente". [70] En Metacritic , la película tiene un promedio ponderado de 47 sobre 100, basado en 44 críticos, lo que indica "críticas mixtas o promedio". [71] Las audiencias encuestadas por CinemaScore le dieron a la película una calificación poco común de "A +". [72]

En una reseña positiva para Time , su crítico Richard Corliss calificó La pasión de Cristo como "una película seria, hermosa e insoportable que irradia un compromiso total". [71] El crítico de cine de New York Press Armond White elogió la dirección de Gibson, comparándolo con Carl Theodor Dreyer en cómo transformó el arte en espiritualidad. [73] White también señaló que era extraño ver al director Mel Gibson ofrecer al público "un desafío intelectual" con la película. [74] Roger Ebert del Chicago Sun-Times gave the movie four out of four stars, calling it "the most violent film I have ever seen" as well as reflecting on how it struck him, a former altar boy: "What Gibson has provided for me, for the first time in my life, is a visceral idea of what the Passion consisted of. That his film is superficial in terms of the surrounding message—that we get only a few passing references to the teachings of Jesus—is, I suppose, not the point. This is not a sermon or a homily, but a visualization of the central event in the Christian religion. Take it or leave it."[75]

In a negative review, Slate magazine's David Edelstein called it "a two-hour-and-six-minute snuff movie",[76] and Jami Bernard of the New York Daily News felt it was "the most virulently anti-Semitic movie made since the German propaganda films of World War II".[77] Writing for the Dallas Observer, Robert Wilonsky stated that he found the movie "too turgid to awe the nonbelievers, too zealous to inspire and often too silly to take seriously, with its demonic hallucinations that look like escapees from a David Lynch film; I swear I couldn't find the devil carrying around a hairy-backed midget anywhere in the text I read."[71]

The June 2006 issue of Entertainment Weekly named The Passion of the Christ the most controversial film of all time, followed by Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971).[78] In 2010, Time listed it as one of the most "ridiculously violent" films of all time.[79]

Independent promotion and discussion[edit]

A number of independent websites, such as MyLifeAfter.com and Passion-Movie.com, were launched to promote the film and its message and to allow people to discuss the film's effect on their lives. Documentaries such as Changed Lives: Miracles of the Passion chronicled stories of miraculous savings, forgiveness, newfound faith, and the story of a man who confessed to murdering his girlfriend after authorities determined her death was due to suicide.[80] Another documentary, Impact: The Passion of the Christ, chronicled the popular response of the film in the United States, India, and Japan and examined the claims of antisemitism against Mel Gibson and the film.

Accolades[edit]

Wins[edit]

- National Board of Review – Freedom of Expression (tie)

- People's Choice Awards – Favorite Motion Picture Drama

- Satellite Awards – Best Director

- Ethnic Multicultural Media Academy (EMMA Awards) – Best Film Actress – Maia Morgenstern

- Motion Picture Sound Editors (Golden Reel Awards) – Best Sound Editing in a Feature Film – Music – Michael T. Ryan

- American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers – ASCAP Henry Mancini Award – John Debney[citation needed]

- Hollywood Film Festival, US – Hollywood Producer of the Year – Mel Gibson[81][82]

- GMA Dove Award, The Passion of the Christ Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Instrumental Album of the Year

- Golden Eagle Award – Best Foreign Language Film[83]

Nominations[edit]

- Academy Awards

- Best Cinematography – Caleb Deschanel

- Best Makeup – Keith Vanderlaan, Christien Tinsley

- Best Original Score – John Debney

- American Society of Cinematographers – Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in Theatrical Releases – Caleb Deschanel

- Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards – Best Popular Movie

- Irish Film and Television Awards – Jameson People's Choice Award for Best International Film

- MTV Movie Awards – Best Male Performance – Jim Caviezel

Other honors[edit]

The film was nominated in the following categories for American Film Institute recognition:

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[84]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10 – Nominated Epic Film[85]

Rewritten on the Podcast "Never Seen It with Kyle Ayers" by comedian Ahri Findling[86]

Controversies[edit]

Questions of historical and biblical accuracy[edit]

Despite criticisms that Gibson deliberately added material to the historical accounts of first-century Judea and biblical accounts of Christ's crucifixion, some scholars defend the film as not being primarily concerned with historical accuracy. Biblical scholar Mark Goodacre protested that he could not find one documented example of Gibson explicitly claiming the film to be historically accurate.[87][88] Gibson has been quoted as saying: "I think that my first duty is to be as faithful as possible in telling the story so that it doesn't contradict the Scriptures. Now, so long as it didn't do that, I felt that I had a pretty wide berth for artistic interpretation, and to fill in some of the spaces with logic, with imagination, with various other readings."[89] One such example is a scene in which Satan is seen carrying a demonic baby during Christ's flogging, construed as a perversion of traditional depictions of the Madonna and Child, and also as a representation of Satan and the Antichrist. Gibson's description:

It's evil distorting what's good. What is more tender and beautiful than a mother and a child? So the Devil takes that and distorts it just a little bit. Instead of a normal mother and child you have an androgynous figure holding a 40-year-old 'baby' with hair on his back. It is weird, it is shocking, it's almost too much—just like turning Jesus over to continue scourging him on his chest is shocking and almost too much, which is the exact moment when this appearance of the Devil and the baby takes place.[90]

When asked about the film's faithfulness to the account given in the New Testament, Father Augustine Di Noia of the Vatican's Doctrinal Congregation replied: "Mel Gibson's film is not a documentary... but remains faithful to the fundamental structure common to all four accounts of the Gospels" and "Mel Gibson's film is entirely faithful to the New Testament".[91]

Disputed papal endorsement[edit]

On December 5, 2003, Passion of the Christ co-producer Stephen McEveety gave the film to Archbishop Stanisław Dziwisz, the pope's secretary.[92] John Paul II watched the film in his private apartment with Archbishop Dziwisz on Friday and Saturday, December 5 and 6, and later met with McEveety.[93] Jan Michelini, an Italian and the movie's assistant director, was also there when Dziwisz and McEveety met.[94][95] On December 16, Variety reported the pope, a movie buff, had watched a rough version of the film.[96] On December 17, Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan reported John Paul II had said "It is as it was", sourcing McEveety, who said he heard it from Dziwisz.[3] Noonan had emailed Joaquín Navarro-Valls, the head of the Vatican's press office, for confirmation before writing her December 17 column, surprised that the "famously close-mouthed" Navarro-Valls had approved the use of the "It is as it was" quote, and his emailed response stated he had no other comment at that time.[97] National Catholic Reporter journalist John L. Allen Jr., published a similar account on the same day, quoting an unnamed senior Vatican official.[93] On December 18, Reuters[97] and the Associated Press independently confirmed the story, citing Vatican sources.[98]

On December 24, an anonymous Vatican official told Catholic News Service "There was no declaration, no judgment from the pope." On January 9, Allen defended his earlier reporting, saying that his official source was adamant about the veracity of the original story.[93] On January 18, columnist Frank Rich for The New York Times wrote that the statement was "being exploited by the Gibson camp", and that when he asked Michelini about the meeting, Michelini said Dziwisz had reported the pope's words as "It is as it was", and said the pope also called the film "incredibile", an Italian word Michelini translated as "amazing".[94] The next day Archbishop Dziwisz told CNS, "The Holy Father told no one his opinion of this film."[95] This denial resulted in a round of commentators who accused the film producers of fabricating a papal quote to market their movie.

On January 19, 2004, Gabriel Snyder reported in Variety that before McEveety spoke to Noonan, he had requested and received permission from the Vatican to use the "It is as it was" quote.[99] Two days later, after receiving a leaked copy of an email from someone associated with Gibson, Rod Dreher reported in the Dallas Morning News that McEveety was sent an email on December 28 allegedly from papal spokesman Navarro-Valls that supported the Noonan account, and suggested "It is as it was" could be used as the leitmotif in discussions on the film and said to "Repeat the words again and again and again."[100]

Further complicating the situation, on January 21[97] Dreher emailed Navarro-Valls a copy of the December 28 email McEveety had received, and Navarro-Valls emailed Dreher back and said, "I can categorically deny its authenticity."[100] Dreher opined that either Mel Gibson's camp had created "a lollapalooza of a lie", or the Vatican was making reputable journalists and filmmakers look like "sleazebags or dupes" and he explained:

Interestingly, Ms. Noonan reported in her Dec. 17 column that when she asked the spokesman if the pope had said anything more than "It is as it was," he e-mailed her to say he didn't know of any further comments. She sent me a copy of that e-mail, which came from the same Vatican email address as the one to me and to Mr. McEveety.[100]

On January 22, Noonan noted that she and Dreher had discovered the emails were sent by "an email server in the Vatican's domain" from a Vatican computer with the same IP address.[97] The Los Angeles Times reported that, when it asked on December 19 when the story first broke if the "It is as it was" quote was reliable, Navarro-Valls had responded "I think you can consider that quote as accurate."[101] In an interview with CNN on January 21, Vatican analyst John L. Allen Jr. noted that while Dziwisz stated that Pope John Paul II made no declaration about this movie, other Vatican officials were "continuing to insist" the pope did say it, and other sources claimed they had heard Dziwisz say the pope said it on other occasions, and Allen called the situation "kind of a mess".[102] A representative from Gibson's Icon Productions expressed surprise at Dziwisz's statements after the correspondence and conversations between film representatives and the pope's official spokesperson, Navarro-Valls, and stated "there is no reason to believe that the pope's support of the film 'isn't as it was.'"[99]

On January 22, after speaking to Dziwisz, Navarro-Valls confirmed John Paul II had seen The Passion of the Christ, and released the following official statement:

The film is a cinematographic transposition of the historical event of the Passion of Jesus Christ according to the accounts of the Gospel. It is a common practice of the Holy Father not to express public opinions on artistic works, opinions that are always open to different evaluations of aesthetic character.[98]

On January 22 in The Wall Street Journal, Noonan addressed the question of why the issues being raised were not just "a tempest in a teapot" and she explained:[97]

The truth matters. What a pope says matters. And what this pontiff says about this film matters. The Passion, which is to open on Feb. 25, has been the focus of an intense critical onslaught since last summer. The film has been fiercely denounced as anti-Semitic, and accused of perpetuating stereotypes that will fan hatred against Jews. John Paul II has a long personal and professional history of opposing anti-Semitism, of working against it, and of calling for dialogue, respect and reconciliation between all religions. His comments here would have great importance.

Allegations of antisemitism[edit]

Before the film was released, there were prominent criticisms of perceived antisemitic content in the film. It was for that reason that 20th Century Fox told New York Assemblyman Dov Hikind it had passed on distributing the film in response to a protest outside the News Corporation building. Hikind warned other companies that "they should not distribute this film. This is unhealthy for Jews all over the world."[34]

A joint committee of the Secretariat for Ecumenical and Inter-religious Affairs of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Department of Inter-religious Affairs of the Anti-Defamation League obtained a version of the script before it was released in theaters. They released a statement, calling it

one of the most troublesome texts, relative to anti-Semitic potential, that any of us had seen in 25 years. It must be emphasized that the main storyline presented Jesus as having been relentlessly pursued by an evil cabal of Jews, headed by the high priest Caiaphas, who finally blackmailed a weak-kneed Pilate into putting Jesus to death. This is precisely the storyline that fueled centuries of anti-Semitism within Christian societies. This is also a storyline rejected by the Roman Catholic Church at Vatican II in its document Nostra aetate, and by nearly all mainline Protestant churches in parallel documents...Unless this basic storyline has been altered by Mr. Gibson, a fringe Catholic who is building his own church in the Los Angeles area and who apparently accepts neither the teachings of Vatican II nor modern biblical scholarship, The Passion of the Christ retains a real potential for undermining the repudiation of classical Christian anti-Semitism by the churches in the last 40 years.[103]

The ADL itself also released a statement about the yet-to-be-released film:

For filmmakers to do justice to the biblical accounts of the passion, they must complement their artistic vision with sound scholarship, which includes knowledge of how the passion accounts have been used historically to disparage and attack Jews and Judaism. Absent such scholarly and theological understanding, productions such as The Passion could likely falsify history and fuel the animus of those who hate Jews.[104]

Rabbi Daniel Lapin, the head of the Toward Tradition organization, criticized this statement, and said of Abraham Foxman, the head of the ADL, "what he is saying is that the only way to escape the wrath of Foxman is to repudiate your faith".[105]

In The Nation, reviewer Katha Pollitt wrote: "Gibson has violated just about every precept of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops own 1988 'Criteria' for the portrayal of Jews in dramatizations of the Passion (no bloodthirsty Jews, no rabble, no use of Scripture that reinforces negative stereotypes of Jews.) [...] The priests have big noses and gnarly faces, lumpish bodies, yellow teeth; Herod Antipas and his court are a bizarre collection of oily-haired, epicene perverts. The 'good Jews' look like Italian movie stars (Italian sex symbol Monica Bellucci is Mary Magdalene); Jesus's mother, who would have been around 50 and appeared 70, could pass for a ripe 35."[106] Jesuit priest Fr. William Fulco, S.J. of Loyola Marymount University—and the film's translator for Hebrew dialogue—specifically disagreed with that assessment, and disagreed with concerns that the film accused the Jewish community of deicide.[107]

One specific scene in the film perceived as an example of anti-Semitism was in the dialogue of Caiaphas, when he states "His blood [is] on us and on our children!", a quote historically interpreted by some as a curse taken upon by the Jewish people. Certain Jewish groups asked this be removed from the film. However, only the subtitles were removed; the original dialogue remains in the Hebrew soundtrack.[108] When asked about this scene, Gibson said: "I wanted it in. My brother said I was wimping out if I didn't include it. But, man, if I included that in there, they'd be coming after me at my house. They'd come to kill me."[109] In another interview when asked about the scene, he said, "It's one little passage, and I believe it, but I don't and never have believed it refers to Jews, and implicates them in any sort of curse. It's directed at all of us, all men who were there, and all that came after. His blood is on us, and that's what Jesus wanted. But I finally had to admit that one of the reasons I felt strongly about keeping it, aside from the fact it's true, is that I didn't want to let someone else dictate what could or couldn't be said."[110]

Additionally, the film's suggestion that the Temple's destruction was a direct result of the Sanhedrin's actions towards Jesus could also be interpreted as an offensive take on an event which Jewish tradition views as a tragedy, and which is still mourned by many Jews today on the fast day of Tisha B'Av.[111]

Reactions to allegations of antisemitism[edit]

Film critic Roger Ebert, who awarded The Passion of the Christ 4 out of 4 stars in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times, denied allegations that the film was anti-semitic. Ebert described the film as "a powerful and important film, helmed by a man with a sincere heart and a warrior's sense of justice. It is a story filled with searing images and ultimately a message of redemption and hope." Ebert said "It also might just be the greatest cinematic version of the greatest story ever told."[112]

Conservative columnist Cal Thomas also disagreed with allegations of antisemitism, stating "To those in the Jewish community who worry that the film might contain anti-Semitic elements, or encourage people to persecute Jews, fear not. The film does not indict Jews for the death of Jesus."[113] Two Orthodox Jews, Rabbi Daniel Lapin and conservative talk-show host and author Michael Medved, also vocally rejected claims that the film is antisemitic. They said the film contains many sympathetic portrayals of Jews: Simon of Cyrene (who helps Jesus carry the cross), Mary Magdalene, the Virgin Mary, St. Peter, St. John, Veronica (who wipes Jesus' face and offers him water) and several Jewish priests who protest Jesus' arrest (Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea) during Caiaphas' trial of Jesus.

Bob Smithouser of Focus on the Family's Plugged In also believed that film was trying to convey the evils and sins of humanity rather than specifically targeting Jews, stating: "The anthropomorphic portrayal of Satan as a player in these events brilliantly pulls the proceedings into the supernatural realm—a fact that should have quelled the much-publicized cries of anti-Semitism since it shows a diabolical force at work beyond any political and religious agendas of the Jews and Romans."[62]

Moreover, senior officer at the Vatican Cardinal Darío Castrillón Hoyos, who had seen the film, addressed the matter so:

Anti-Semitism, like all forms of racism, distorts the truth in order to put a whole race of people in a bad light. This film does nothing of the sort. It draws out from the historical objectivity of the Gospel narratives sentiments of forgiveness, mercy, and reconciliation. It captures the subtleties and the horror of sin, as well as the gentle power of love and forgiveness, without making or insinuating blanket condemnations against one group. This film expressed the exact opposite, that learning from the example of Christ, there should never be any more violence against any other human being.[114]

Asked by Bill O'Reilly if his movie would "upset Jews", Gibson responded "It's not meant to. I think it's meant to just tell the truth. I want to be as truthful as possible."[115] In an interview for The Globe and Mail, he added: "If anyone has distorted Gospel passages to rationalize cruelty towards Jews or anyone, it's in defiance of repeated Papal condemnation. The Papacy has condemned racism in any form...Jesus died for the sins of all times, and I'll be the first on the line for culpability."[116]

South Park parodied the controversy in the episodes "Good Times with Weapons", "Up the Down Steroid" and "The Passion of the Jew", all of which aired just a few weeks after the film's release.

Criticism of excessive violence[edit]

A.O. Scott in The New York Times wrote "The Passion of the Christ is so relentlessly focused on the savagery of Jesus' final hours that this film seems to arise less from love than from wrath, and to succeed more in assaulting the spirit than in uplifting it."[117] David Edelstein, Slate's film critic, dubbed the film "a two-hour-and-six-minute snuff movie—The Jesus Chainsaw Massacre—that thinks it's an act of faith", and further criticized Gibson for focusing on the brutality of Jesus' execution, instead of his religious teachings.[76] In 2008, writer Michael Gurnow in American Atheists stated much the same, labeling the work a mainstream snuff film.[118] Critic Armond White, in his review of the film for Africana.com offered another perspective on the violence in the film. He wrote, "Surely Gibson knows (better than anyone in Hollywood is willing to admit) that violence sells. It's problematic that this time, Gibson has made a film that asks for a sensitive, serious, personal response to violence rather than his usual glorifying of vengeance."[74]

During Diane Sawyer's interview of him, Gibson said:

I wanted it to be shocking; and I wanted it to be extreme...So that they see the enormity of that sacrifice; to see that someone could endure that and still come back with love and forgiveness, even through extreme pain and suffering and ridicule. The actual crucifixion was more violent than what was shown on the film, but I thought no one would get anything out of it.

Sequel[edit]

In June 2016, writer Randall Wallace stated that he and Gibson had begun work on a sequel to The Passion of the Christ focusing on the resurrection of Jesus.[119] Wallace previously worked with Gibson as the screenwriter for Braveheart and director of We Were Soldiers.[120] In September of that year, Gibson expressed his interest in directing it. He estimated that release of the film was still "probably three years off",[121] stating that "it is a big project".[122] Gibson implied that part of the movie would be taking place in Hell and, while talking to Raymond Arroyo, said that it also may show flashbacks depicting the fall of the Angels.[123] The film will explore the three-day period starting on Good Friday, the day of Jesus' death.[124]

In January 2018, Caviezel was in agreements with Mel Gibson to reprise his role as Jesus in the sequel.[125] In March 2020, Caviezel stated in an interview that the film was in its fifth draft.[126] However, in September 2020, Caviezel then said that Gibson had sent him the third draft of the screenplay. [127][128]

See also[edit]

- Depiction of Jesus

- Passion of Jesus

References[edit]

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ (18)". British Board of Film Classification. February 18, 2004. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "The Passion of the Christ (2004): summary". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ a b Noonan, Peggy (December 17, 2003). "'It is as it was': Mel Gibson's The Passion gets a thumbs-up from the pope". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ a b Father John O'Malley A Movie, a Mystic, a Spiritual Tradition America, March 15, 2004 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 5, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ a b c Jesus and Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ by Kathleen E. Corley, Robert Leslie Webb. 2004. ISBN 0-8264-7781-X. pp. 160–161.

- ^ a b c Mel Gibson's Passion and philosophy by Jorge J. E. Gracia. 2004. ISBN 0-8126-9571-2. p. 145.

- ^ a b Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia edited by Philip C. Dimare. 2011. ISBN 1-59884-296-X. p. 909.

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ". Movie-Locations

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ "Christian Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ Gibson, Mel (February 25, 2004), The Passion of the Christ, retrieved September 1, 2016

- ^ The Holy Bible, Book of Revelation 21:5.

- ^ The Holy Bible, Book of Isaiah 53:5.

- ^ The Holy Bible, Book of Genesis 3:15.

- ^ Cooney Carrillo, Jenny (February 26, 2004). "The Passion of Mel". Urbancinefile.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Abramowitz, Rachel (March 7, 2004). "Along came Mary; Mel Gibson was sold on Maia Morgenstern for 'Passion' at first sight". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Brentano, Clement. The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

- ^ Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia edited by Philip C. DiMare 2011 ISBN 1-59884-296-X p. 909

- ^ a b Emmerich, Anne Catherine, and Clemens Brentano. The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Anvil Publishers, Georgia, 2005 pp. 49–56

- ^ John Thavis, Catholic News Service February 4, 2004: "Vatican confirms papal plans to beatify nun who inspired Gibson film" [1]

- ^ John Thavis, Catholic News Service October 4, 2004: "Pope beatifies five, including German nun who inspired Gibson film" [2]

- ^ "Mel Gibson's great passion: Christ's agony as you've never seen it". Zenit News Agency. March 6, 2003. Archived from the original on August 15, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ 'Msgr. Charles Pope' "A Hidden, Mysterious, and Much Debated Word in the Our Father". May 6, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Translating the passion". Language Hat. March 8, 2004.

- ^ Jarvis, Edward (2018). Sede Vacante: The Life and Legacy of Archbishop Thuc. Berkeley CA: The Apocryphile Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1949643022.

- ^ Susman, Gary (October 24, 2003). "Charged Performance". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ Ross, Scott (March 28, 2008). "Behind the Scenes of 'The Passion' with Jim Caviezel". Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ "Jesus actor struck by lightning". BBC News. October 23, 2003. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ "Jack Lenz Bio". JackLenz.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015.

- ^ "Clips of Musical Compositions by Jack Lenz". JackLenz.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015.

- ^ Susman, Gary (October 16, 2004). "Napoleon Branding". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (September 23, 2002). "Gibson To Direct Christ Tale With Caviezel As Star". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Patsuris, Penelope (March 3, 2004). "What Mel's Passion Will Earn Him". Forbes.com.

- ^ a b "Fox passes on Gibson's 'The Passion'". Los Angeles Times. October 22, 2004. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Horn, John (October 22, 2004). "Gibson to Market 'Christ' on His Own, Sources Say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Cobb, Jerry (February 25, 2004). "Marketing 'The Passion of the Christ'". NBC News.

- ^ Maresco, Peter A. (Fall 2004). "Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ: Market Segmentation, Mass Marketing and Promotion, and the Internet". Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c "Many churches look to 'Passion' as evangelism tool". United Methodist Church. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- ^ ANN News Analysis: Adventists and "The Passion of the Christ", Adventist News Network, 23 February 2004

- ^ Pauley, John L.; King, Amy (2013). Woods, Robert H. (ed.). Evangelical Christians and Popular Culture. 1. Westport: Praeger Publishing. pp. 36–51. ISBN 978-0313386541.

- ^ Pawley, p. 38.

- ^ Pawley, p. 40.

- ^ Pawley, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Pauley, p. 41.

- ^ Fredriksen, Paula (2006). On 'The Passion of the Christ': Exploring the Issues Raised by the Controversial Movie. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520248533.[page needed]

- ^ "All time box office: domestic grosses by MPAA rating". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ DeSantis, Nick (February 22, 2016). "'Deadpool' Box Office On Pace To Dethrone 'Passion Of The Christ' As Top-Grossing R-Rated Movie Of All Time". Forbes. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (February 27, 2016). "Powerless Versus 'Deadpool', 'Gods of Egypt' Is First 2016 Big-Budget Bomb: Saturday AM B.O. Update". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (February 28, 2016). "Box Office: 'Deadpool' Entombs Big-Budget Bomb 'Gods of Egypt' to Stay No. 1". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (March 6, 2016). "Box Office: 'Zootopia' Defeats 'Deadpool' With Record $73.7M". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ (2004): domestic total estimated tickets". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ "'The Passion of the Christ': "A milestone in the cinema history"". Asia News. PIME Onlus – AsiaNews. April 7, 2004. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Passion Of The Christ Goes International". Worldpress.org. May 2004. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

A Philippine student shows a pirated DVD copy of The Passion of the Christ, which opened in local theaters, March 31, 2004.

- ^ Flores, Wilson Lee (March 29, 2004). "Mel Gibson's 'Passion' is powerful, disturbing work of art". Philstar.com. Gottingen, Germany: Philstar Global Corp. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Aravilla, Jose (March 11, 2004). "Bishops endorse Mel Gibson film". Philstar.com. Philstar Global Corp. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Censors in Malaysia give OK to 'Passion'". Los Angeles Times. July 10, 2004. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ King, Laura (March 15, 2004). "'Passion' goes unseen in Israel". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Blanford, Nicholas (April 9, 2004). "Gibson's movie unlikely box-office hit in Arab world". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "2004 Box Office Totals for Egypt". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ O'Neill, Eddie (February 2, 2014). "'The Passion of the Christ', a Decade Later". National Catholic Register. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ^ Frater, Patrick (August 8, 2017). "'Wolf Warriors II' Takes All Time China Box Office Record". Variety. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c "The Passion of the Christ Review". Plugged In. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Passion Recut: domestic total gross". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Hettrick, Scott (September 1, 2004). "DVD buyers express 'Passion'". Variety. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Associated Press (September 1, 2004). "Passion DVD sells 4.1 million in one day". Today. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ Gibson, Mel. The Passion of the Christ (Blu-ray; visual material) (in Latin and Hebrew) (definitive ed.). Beverly Hills, California: 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment. OCLC 302426419. Retrieved March 29, 2013. Lay summary – Amazon.

- ^ Papamichael, Stella. "The Passion of the Christ: Special Edition DVD". BBC. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's 'The Passion of the Christ' Returns to Blu-ray". High-Def Digest.

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ". TBN. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c "The Passion of the Christ (2004): reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (August 19, 2011). "Why CinemaScore matters for box office". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- ^ White, Armond (March 18, 2008). "Steve McQueen's Hunger". New York Press. Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ a b White, Armond (February 26, 2004). "Africana Reviews: The Passion of the Christ (web archive)". Archived from the original on March 12, 2004.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 24, 2004). "The Passion of the Christ". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 2, 2006 – via rogerebert.com.

- ^ a b Edelstein, David (February 24, 2004). "Jesus H. Christ". Slate. Archived from the original on November 23, 2009.

- ^ Bernard, Jami (February 24, 2004). "The Passion of the Christ". New York Daily News. New York City: Tronc. Archived from the original on April 16, 2004.

- ^ "Entertainment Weekly". June 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Sanburn, Josh (September 3, 2010). "Top 10 Ridiculously Violent Movies". Time. New York City. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ "Film prompts murder confession". Edinburgh: News.scotsman.com. March 27, 2004. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "Mel Gibson". IMDb. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ "Hollywood Awards ... and the winners are ..." Hollywood Film Awards. October 19, 2004. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ Золотой Орел 2004 [Golden Eagle 2004] (in Russian). Ruskino.ru. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's Top 10 Epic Nominations". Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Never Seen It".

- ^ Goodacre, Mark (May 2, 2004). "Historical Accuracy of The Passion of the Christ". Archived from the original on October 13, 2008.

- ^ Mark Goodacre, "The Power of The Passion: Reacting and Over-reacting to Gibson's Artistic Vision" in "Jesus and Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. The Film, the Gospels and the Claims of History", ed. Kathleen E. Corley and Robert L. Webb, 2004

- ^ Neff, David, and Struck, Jane Johnson (February 23, 2004). "'Dude, that was graphic': Mel Gibson talks about The Passion of The Christ". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Moring, Mark (March 1, 2004). "What's up with the ugly baby?". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's Passion: on review at the Vatican". Zenit News Agency. December 8, 2003. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Flynn, J. D. (December 18, 2003). "Pope John Paul endorses The Passion of Christ with five simple words". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c Allen, John L. Jr. (January 9, 2004)."U.S. bishops issue abuse report; more on The Passion ...". National Catholic Reporter: The Word from Rome. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ a b Rich, Frank (January 18, 2014). "The pope's thumbs up for Gibson's Passion". The New York Times Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Wooden, Cindy (January 19, 2004). "Pope never commented on Gibson's 'Passion' film, says papal secretary". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on January 24, 2004.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (December 15, 2003)."Pope peeks at private Passion preview". Variety. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Noonan, Peggy (January 22, 2004). "The story of the Vatican and Mel Gibson's film gets curiouser". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ a b Allen, John L. Jr. (January 23, 2004)."Week of prayer for Christian unity; update on The Passion ...". National Catholic Reporter: The Word from Rome. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ a b Snyder, Gabriel (January 19, 2004)."Did Pope really plug Passion? Church denies papal support of Gibson's pic". Variety. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c Dreher, Rod (January 21, 2004)."Did the Vatican endorse Gibson's film – or didn't it?" Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on January 27, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ^ Munoz, Lorenza and Stammer, Larry B. (January 23, 2004)." Fallout over Passion deepens". The Los Angeles Times. Contributions by Greg Braxton and the Associated Press. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "Transcripts: The Passion stirs controversy at the Vatican". CNN. Miles O'Brien interview with John L. Allen Jr. on January 21, 2004. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Pawlikowski, John T. (February 2004). "Christian Anti-Semitism: Past History, Present Challenges Reflections in Light of Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ". Journal of Religion and Film. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006.

- ^ "ADL Statement on Mel Gibson's 'The Passion'" (Press release). Anti-Defamation League. June 24, 2003. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008.

- ^ Cattan, Nacha (March 5, 2004). "'Passion' Critics Endanger Jews, Angry Rabbis Claim, Attacking Groups, Foxman". The Jewish Daily Forward.

- ^ Pollitt, Katha (March 11, 2004). "The Protocols of Mel Gibson". The Nation. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ Wooden, Cindy (May 2, 2003). "As filming ends, 'Passion' strikes some nerves". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ Vermes, Geza (February 27, 2003). "Celluloid brutality". The Guardian. London. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ "The Jesus War".

- ^ Lawson, Terry (February 17, 2004). "Mel Gibson and Other 'Passion' Filmakers say the Movie was Guided by Faith". Detroit Free Press.[dead link]

- ^ Markoe, Lauren (July 15, 2013). "Tisha B'Av 2013: A New Approach To A Solemn Jewish Holiday". Huffington Post.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 30, 2004). "Judge ye not Gibson's film until you've actually seen it". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "The Greatest Story Ever Filmed". TownHall.com. August 5, 2003.

- ^ Gaspari, Antonio (September 18, 2003). "The Cardinal & the Passion". National Review Online. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (January 19, 2003). "The Passion of Mel Gibson". Time. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Interview". The Globe and Mail. February 14, 2004.

- ^ A. O. Scott (February 25, 2004). "Good and Evil Locked in Violent Showdown". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- ^ Gurnow, Michael (April 2008). "The passion of the snuff: how the MPAA allowed a horror film to irreparably scar countless young minds in the name of religion" (PDF). American Atheists. pp. 17–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 18, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ Bond, Paul (June 9, 2016)."Mel Gibson planning Passion of the Christ sequel (exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ Dostis, Melanie (June 9, 2019)."Mel Gibson is working on a Passion of the Christ sequel". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Confirms Sequel To 'Passion Of The Christ'" (Interview).

- ^ Mike Fleming Jr (September 6, 2016). "Mel Gibson On His Venice Festival Comeback Picture 'Hacksaw Ridge' – Q&A". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ "Gibson on Passion of the Christ Sequel, The Resurrection" (Interview).

- ^ Scott, Ryan (November 2, 2016)."'Passion of the Christ 2' gets titled Resurrection, may take Jesus to Hell". MovieWeb. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ Bond, Paul (January 30, 2018). "Jim Caviezel in Talks to Play Jesus in Mel Gibson's 'Passion' Sequel". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ "'The Passion of the Christ' actor: Painful movie 'mistakes' made hit film 'more beautiful'". Fox Nation. March 23, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Burger, John (September 25, 2020). "Jim Caviezel to play Jesus again in sequel to 'The Passion of Christ'". Aleteia. Aleteia SAS. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Guno, Nina V. (September 24, 2020). "'Passion of the Christ 2' is coming, says Jim Caviezel". Inquirer Entertainment. INQUIRER.net. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Passion of the Christ |

- The Passion of the Christ at IMDb

- The Passion of the Christ at the TCM Movie Database

- The Passion of the Christ at AllMovie

- The Passion of the Christ at Box Office Mojo

- The Passion of the Christ at Metacritic

- The Passion of the Christ at Rotten Tomatoes