| Parte de una serie sobre el |

| Biblia |

|---|

|

| Esquema de temas relacionados con la Biblia portal bíblico |

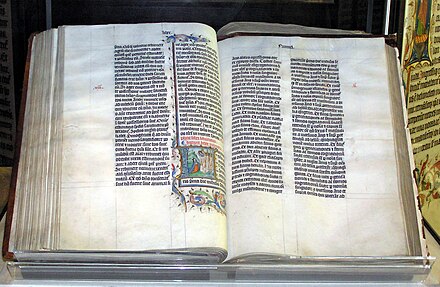

Un canon bíblico , también llamado canon de las escrituras , es un conjunto de textos (o "libros") que una comunidad religiosa judía o cristiana en particular considera escrituras autorizadas . [1] La palabra inglesa canon proviene del griego κανών, que significa " regla " o " vara de medir ". Los cristianos fueron los primeros en usar el término en referencia a las escrituras, pero Eugene Ulrich considera la noción como judía. [2] [3]

La mayoría de los cánones enumerados a continuación son considerados por los adherentes como "cerrados" (es decir, no se pueden agregar ni quitar libros), [4] lo que refleja la creencia de que la revelación pública ha terminado y, por lo tanto, alguna persona o personas pueden reunir textos inspirados aprobados en un canon completo y autorizado, que el erudito Bruce Metzger define como "una colección autorizada de libros". [5] En contraste, un "canon abierto", que permite la adición de libros a través del proceso de revelación continua , Metzger lo define como "una colección de libros autorizados".

Estos cánones se han desarrollado mediante el debate y el acuerdo de las autoridades religiosas de sus respectivas creencias y denominaciones. Algunos libros, como los evangelios judeo-cristianos , se han excluido de varios cánones por completo, pero muchos libros en disputa se consideran apócrifos bíblicos o deuterocanónicos.por muchos, mientras que algunas denominaciones pueden considerarlos completamente canónicos. Existen diferencias entre la Biblia hebrea y los cánones bíblicos cristianos, aunque la mayoría de los manuscritos son comunes. En algunos casos donde se han acumulado diversos estratos de inspiración bíblica, es prudente discutir textos que solo tienen un estatus elevado dentro de una tradición particular. Esto se vuelve aún más complejo cuando se consideran los cánones abiertos de las diversas sectas Santos de los Últimos Días y las revelaciones bíblicas que supuestamente se dieron a varios líderes a lo largo de los años dentro de ese movimiento .

Los diferentes grupos religiosos incluyen diferentes libros en sus cánones bíblicos, en diferentes órdenes y, a veces, dividen o combinan libros. El Tanakh judío (a veces llamado Biblia hebrea ) contiene 24 libros divididos en tres partes: los cinco libros de la Torá ("enseñanza"); los ocho libros de los Nevi'im ("profetas"); y los once libros de Ketuvim ("escritos"). Está compuesto principalmente en hebreo bíblico . La Septuaginta griega se parece mucho a la Biblia hebrea, pero incluye textos adicionales, es la principal fuente textual del Antiguo Testamento griego cristiano. [6]

Las Biblias cristianas van desde los 73 libros del canon de la Iglesia Católica , los 66 libros del canon de algunas denominaciones o los 80 libros del canon de otras denominaciones de protestantes , hasta los 81 libros del canon de la Iglesia Etíope Ortodoxa Tewahedo . La primera parte de las Biblias cristianas es el Antiguo Testamento , que contiene, como mínimo, los 24 libros anteriores de la Biblia hebrea, pero divididos en 39 (protestantes) o 46 (católicos) y ordenados de manera diferente. La segunda parte es el Nuevo Testamento , que contiene 27 libros; los cuatro evangelios canónicos , Hechos de los Apóstoles , 21 epístolas o cartas y elLibro de Apocalipsis . Por ejemplo, la Biblia King James contiene 80 libros: 39 en su Antiguo Testamento, 14 en su Apócrifo y 27 en su Nuevo Testamento.

La Iglesia católica y las iglesias cristianas orientales sostienen que ciertos libros y pasajes deuterocanónicos son parte del canon del Antiguo Testamento . Las iglesias cristianas ortodoxas orientales , ortodoxas orientales y asirias pueden tener pequeñas diferencias en sus listas de libros aceptados. La lista que se proporciona aquí para estas iglesias es la más inclusiva: si al menos una iglesia oriental acepta el libro, se incluye aquí.

Cánones judíos

Judaísmo rabínico

| Parte de una serie sobre |

| judaísmo |

|---|

|

|

El judaísmo rabínico (en hebreo: יהדות רבנית) reconoce los veinticuatro libros del Texto Masorético , comúnmente llamado Tanakh (en hebreo: תַּנַ"ךְ) o Biblia hebrea . [7] La evidencia sugiere que el proceso de canonización ocurrió entre el 200 a. C. y el 200 a. C. D. C., y una posición popular es que la Torá fue canonizada c. 400 a. C., los Profetas c. 200 a. C. y los Escritos c. 100 d. C. [8] quizás en un hipotético Concilio de Jamnia; sin embargo, esta posición es cada vez más criticada por eruditos modernos. [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14]Según Marc Zvi Brettler , las escrituras judías fuera de la Torá y los Profetas eran fluidas, diferentes grupos veían la autoridad en diferentes libros. [15]

El Libro de Deuteronomio incluye una prohibición contra sumar o restar ( 4: 2 , 12:32 ) que podría aplicarse al libro en sí (es decir, un "libro cerrado", una prohibición contra la edición futura de escribas ) o a la instrucción recibida por Moisés en monte Sinaí . [16] El libro de 2 Macabeos , que en sí mismo no forma parte del canon judío, describe a Nehemías (c. 400 a. C.) como quien "fundó una biblioteca y reunió libros sobre los reyes y profetas, y los escritos de David, y cartas de reyes sobre las ofrendas votivas "( 2: 13-15 ).

El Libro de Nehemías sugiere que el sacerdote-escriba Esdras trajo la Torá de Babilonia a Jerusalén y al Segundo Templo ( 8–9 ) alrededor del mismo período de tiempo. Tanto I como II Macabeos sugieren que Judas Macabeo (c. 167 a. C.) también recopiló libros sagrados ( 3: 42-50 , 2: 13-15 , 15: 6-9 ); de hecho, algunos eruditos argumentan que la dinastía asmonea arregló la historia judía. canon. [17] Sin embargo, estas fuentes primarias no sugieren que el canon estuviera cerrado en ese momento.; además, no está claro que estos libros sagrados fueran idénticos a los que luego pasaron a formar parte del canon.

La Gran Asamblea , también conocida como la Gran Sinagoga, fue, según la tradición judía, una asamblea de 120 escribas, sabios y profetas, en el período comprendido entre el fin de los profetas bíblicos y la época del desarrollo del judaísmo rabínico, marcando una transición de una era de profetas a una era de rabinos. Vivieron en un período de aproximadamente dos siglos que terminó c. 70 d.C. Entre los desarrollos del judaísmo que se les atribuyen están la fijación del canon bíblico judío [fuente requerida], incluidos los libros de Ezequiel, Daniel, Ester y los Doce Profetas Menores; la introducción de la triple clasificación de la Torá Oral , dividiendo su estudio en las tres ramas de midrash , halakot y aggadot; la introducción de la Fiesta de Purim ; y la institución de la oración conocida como Shemoneh 'Esreh , así como las oraciones, rituales y bendiciones de la sinagoga. [ cita requerida ]

Además del Tanaj, la corriente principal del judaísmo rabínico considera que el Talmud (hebreo: תַּלְמוּד) es otro texto central y autorizado. Toma la forma de un registro de discusiones rabínicas relacionadas con la ley , la ética , la filosofía, las costumbres y la historia judías. El Talmud tiene dos componentes: la Mishná (c. 200 d. C.), el primer compendio escrito de la ley oral del judaísmo; y la Guemará (c. 500 d. C.), una elucidación de la Mishná y escritos tannaíticos relacionados que a menudo se aventura en otros temas y expone ampliamente el Tanaj. Hay numerosas citas de Sirach dentro del Talmud, aunque el libro no fue finalmente aceptado en el canon hebreo.

El Talmud es la base de todos los códigos de la ley rabínica y a menudo se cita en otra literatura rabínica . Ciertos grupos de judíos, como los caraítas , no aceptan la Ley oral tal como está codificada en el Talmud y solo consideran que el Tanaj tiene autoridad.

Beta Israel

Los judíos etíopes, también conocidos como Beta Israel ( Ge'ez : ቤተ እስራኤል— Bēta 'Isrā'ēl ), poseen un canon de las escrituras que es distinto del judaísmo rabínico. Mäṣḥafä Kedus (Sagradas Escrituras) es el nombre de la literatura religiosa de estos judíos, que está escrita principalmente en ge'ez. Su libro más sagrado, el Orit , consta del Pentateuco , así como de Josué , Jueces y Rut . El resto del canon judío etíope se considera de importancia secundaria. [ cita requerida ] Consiste en el resto del canon hebreo, con la posible excepción delLibro de Lamentaciones y varios libros deuterocanónicos . Estos incluyen Sirach , Judith , Tobit , 1 y 2 Esdras , 1 y 4 Baruc , los tres libros de Meqabyan , Jubilees , Enoch , [nota 1] el Testamento de Abraham , el Testamento de Isaac y el Testamento de Jacob . Los últimos tres testamentos patriarcales son distintos a esta tradición bíblica. [nota 2]

Un tercer nivel de escritos religiosos que son importantes para los judíos etíopes, pero que no se consideran parte del canon, incluyen los siguientes: Nagara Muse (La conversación de Moisés), Mota Aaron (Muerte de Aaron), Mota Muse (Muerte de Moisés). Moisés), Te'ezaza Sanbat (Preceptos del sábado), Arde'et (Estudiantes), el Apocalipsis de Gorgorios, Mäṣḥafä Sa'atat (Libro de Horas), Abba Elias (Padre Elija), Mäṣḥafä Mäla'əkt (Libro de los Ángeles ), Mäṣḥafä Kahan (Libro de los sacerdotes), Dərsanä Abrəham Wäsara Bägabs (Homilía sobre Abraham y Sara en Egipto), Gadla Sosna(Los Hechos de Susanna) y Baqadāmi Gabra Egzi'abḥēr (En el principio, Dios creó). [ cita requerida ]

Además de estos, Zëna Ayhud (la versión etíope de Josippon ) y los dichos de varios fālasfā (filósofos) son fuentes que no necesariamente se consideran sagradas, pero que, sin embargo, tienen una gran influencia. [ cita requerida ]

Canon samaritano

También existe otra versión de la Torá, en el alfabeto samaritano . Este texto está asociado con los samaritanos (hebreo: שומרונים; árabe: السامريون), un pueblo de quien la Enciclopedia judía afirma: "Su historia como una comunidad distinta comienza con la toma de Samaria por los asirios en el 722 a. C." [18]

La relación del Pentateuco Samaritano con el Texto Masorético todavía se discute. Algunas diferencias son menores, como las edades de las diferentes personas mencionadas en la genealogía, mientras que otras son mayores, como el mandamiento de ser monógamo, que solo aparece en la versión samaritana. Más importante aún, el texto samaritano también difiere del masorético al afirmar que Moisés recibió los Diez Mandamientos en el monte Gerizim, no en el monte Sinaí, y que es en el monte Gerizim donde se deben hacer sacrificios a Dios, no en Jerusalén. No obstante, los eruditos consultan la versión samaritana cuando intentan determinar el significado del texto del Pentateuco original, así como para rastrear el desarrollo de las familias de textos. Algunos rollos entre los rollos del Mar Muertohan sido identificados como tipo de texto proto-samaritano Pentateuco. [19] También se han hecho comparaciones entre la Torá samaritana y la versión de la Septuaginta.

Los samaritanos consideran que la Torá es una escritura inspirada, pero no aceptan ninguna otra parte de la Biblia, probablemente una posición que también ocupaban los saduceos . [20] No ampliaron su canon agregando ninguna composición samaritana. Hay un libro samaritano de Josué ; sin embargo, esta es una crónica popular escrita en árabe y no se considera escritura. Otros textos religiosos samaritanos no canónicos incluyen el Memar Markah ("Enseñanza del Markah") y el Defter (Libro de Oraciones ), ambos del siglo IV o posteriores. [21]

La gente de los remanentes de los samaritanos en la actual Israel / Palestina retiene su versión de la Torá como completa y autoritariamente canónica. [18] Se consideran a sí mismos como los verdaderos "guardianes de la ley". Esta afirmación solo se ve reforzada por la afirmación de la comunidad samaritana en Nablus (un área tradicionalmente asociada con la antigua ciudad de Siquem ) de poseer la copia más antigua de la Torá, una que creen que fue escrita por Abisha, un nieto de Aaron . [22]

Cánones cristianos

| Parte de una serie sobre |

| cristiandad |

|---|

|

Con la posible excepción de la Septuaginta, los apóstoles no dejaron un conjunto definido de escrituras ; en cambio, el canon tanto del Antiguo como del Nuevo Testamento se desarrolló con el tiempo . Las diferentes denominaciones reconocen diferentes listas de libros como canónicos, siguiendo varios concilios de la iglesia y las decisiones de los líderes de varias iglesias.

Para la corriente principal del cristianismo paulino (que surge del cristianismo proto-ortodoxo en tiempos pre-nicenos), qué libros constituían los cánones bíblicos cristianos tanto del Antiguo como del Nuevo Testamento se estableció generalmente en el siglo V, a pesar de algunos desacuerdos académicos, [23] para los antiguos Iglesia indivisa (las tradiciones católica y ortodoxa oriental , antes del cisma Este-Oeste ). El canon católico se estableció en el Concilio de Roma (382), [24] el mismo Concilio encargó a Jerónimo que compilara y tradujera esos textos canónicos alBiblia Vulgata Latina . A raíz de la Reforma Protestante, el Concilio de Trento (1546) afirmó la Vulgata como la Biblia católica oficial con el fin de abordar los cambios que hizo Martín Lutero en su traducción al alemán recientemente completada, que se basó en el idioma hebreo Tanakh además del original. Griego de los textos componentes. Los cánones de la Iglesia de Inglaterra y los presbiterianos ingleses fueron decididos definitivamente por los Treinta y Nueve Artículos (1563) y la Confesión de Fe de Westminster (1647), respectivamente. El Sínodo de Jerusalén (1672) estableció cánones adicionales que son ampliamente aceptados en todo elIglesia ortodoxa .

Varias formas de cristianismo judío persistieron hasta alrededor del siglo V y canonizaron conjuntos de libros muy diferentes, incluidos los evangelios judeocristianos que se han perdido en la historia. Estas y muchas otras obras están clasificadas como apócrifas del Nuevo Testamento por las denominaciones paulinas.

Los cánones del Antiguo y del Nuevo Testamento no se desarrollaron independientemente unos de otros y la mayoría de las fuentes primarias del canon especifican tanto los libros del Antiguo como del Nuevo Testamento. Para conocer la escritura bíblica de ambos Testamentos, aceptada canónicamente en las principales tradiciones de la cristiandad , consulte el canon bíblico § Cánones de varias tradiciones .

Iglesia primitiva

Comunidades cristianas más antiguas

La Iglesia Primitiva usó el Antiguo Testamento , a saber, la Septuaginta (LXX) [25] entre los hablantes de griego, con un canon tal vez como se encuentra en la Lista de Bryennios o el canon de Melito . Los Apóstoles no dejaron de otra manera un conjunto definido de nuevas escrituras ; en cambio, el Nuevo Testamento se desarrolló con el tiempo.

Los escritos atribuidos a los apóstoles circularon entre las primeras comunidades cristianas . Las epístolas paulinas estaban circulando en forma recopilada a finales del siglo I d.C. Justino Mártir , a principios del siglo II, menciona las "memorias de los Apóstoles", que los cristianos (en griego: Χριστιανός) llamaban " evangelios ", y que se consideraban autoritativamente iguales al Antiguo Testamento. [26]

Lista de Marcion

Marción de Sinope fue el primer líder cristiano en la historia registrada (aunque luego se consideró herético ) en proponer y delinear un canon exclusivamente cristiano [27] (c. 140 d. C.). Esto incluyó 10 epístolas de San Pablo , así como una versión del Evangelio de Lucas , que hoy se conoce como el Evangelio de Marción . Al hacer esto, estableció una forma particular de mirar los textos religiosos que persiste en el pensamiento cristiano de hoy. [28]

Después de Marción, los cristianos comenzaron a dividir los textos en aquellos que se alineaban bien con el "canon" (vara de medir) del pensamiento teológico aceptado y los que promovían la herejía. Esto jugó un papel importante en la finalización de la estructura de la colección de obras llamada Biblia. Se ha propuesto que el ímpetu inicial para el proyecto cristiano proto-ortodoxo de canonización fluyó de la oposición a la lista elaborada por Marción. [28]

Padres Apostólicos

Ireneo afirmó un canon de cuatro evangelios (el tetramorfo )en la siguiente cita: "No es posible que los evangelios puedan ser más o menos en número de lo que son. Porque, dado que hay cuatro cuartas partes de la tierra en la que vivimos, y cuatro vientos universales, mientras que la iglesia está esparcidos por todo el mundo, y el 'pilar y baluarte' de la iglesia es el evangelio y el espíritu de vida, es apropiado que ella tenga cuatro pilares que exhalen inmortalidad por todos lados y vivifiquen de nuevo a los hombres ... los evangelios están de acuerdo con estas cosas ... Porque los seres vivientes son cuadriformes y el evangelio es cuadriforme ... Siendo así, todos los que destruyen la forma del evangelio son vanos, ignorantes y también audaces; esos [quiero decir ] quienes representan los aspectos del evangelio como más en número que como se dijo anteriormente, o, por otro lado, menos. "[29]

A principios del siglo III, los teólogos cristianos como Orígenes de Alejandría pueden haber estado usando, o al menos estaban familiarizados con, los mismos 27 libros que se encuentran en las ediciones modernas del Nuevo Testamento, aunque todavía había disputas sobre la canonicidad de algunos de los escritos (ver también Antilegomena ). [30] Asimismo, en el año 200, el fragmento de Muratorian muestra que existía un conjunto de escritos cristianos algo similar a lo que ahora es el Nuevo Testamento, que incluía cuatro evangelios y argumentaba en contra de las objeciones a ellos. [31] Por lo tanto, aunque hubo una buena medida de debate en la Iglesia Primitiva sobre el canon del Nuevo Testamento, los principales escritos fueron aceptados por casi todos los cristianos a mediados del siglo III. [32]

Iglesia del Este

Padres alejandrinos

Orígenes de Alejandría (184 / 85-253 / 54), un erudito temprano involucrado en la codificación del canon bíblico, tenía una educación completa tanto en teología cristiana como en filosofía pagana, pero fue condenado póstumamente en el Segundo Concilio de Constantinopla en 553. ya que algunas de sus enseñanzas fueron consideradas herejías. El canon de Orígenes incluía todos los libros del canon actual del Nuevo Testamento, excepto cuatro libros: Santiago , 2º de Pedro y la 2ª y 3ª epístolas de Juan . [33]

También incluyó al Pastor de Hermas, que luego fue rechazado. El erudito religioso Bruce Metzger describió los esfuerzos de Orígenes, diciendo: "El proceso de canonización representado por Orígenes procedió a través de la selección, pasando de muchos candidatos para su inclusión a menos". [34] Este fue uno de los primeros intentos importantes en la compilación de ciertos libros y cartas como enseñanza autorizada e inspirada para la Iglesia Primitiva en ese momento, aunque no está claro si Orígenes pretendía que su lista tuviera autoridad en sí misma.

En su carta de Pascua de 367, el Patriarca Atanasio de Alejandría dio una lista de exactamente los mismos libros que se convertirían en el Nuevo Testamento –27 libro – protocanon, [35] y usó la frase "ser canonizado" ( kanonizomena ) con respecto a ellos. [36] Atanasio también incluyó el Libro de Baruc , así como la Carta de Jeremías , en su canon del Antiguo Testamento. Sin embargo, de este canon, omitió el Libro de Ester .

Cincuenta Biblias de Constantino

En 331, Constantino I encargó a Eusebio que entregara cincuenta Biblias para la Iglesia de Constantinopla . Atanasio [37] registró a los escribas alejandrinos alrededor de 340 preparando Biblias para Constante . Poco más se sabe, aunque hay mucha especulación. Por ejemplo, se especula que esto puede haber motivado las listas de canon, y que el Codex Vaticanus y el Codex Sinaiticus son ejemplos de estas Biblias. Esos códices contienen casi una versión completa de la Septuaginta ; Al Vaticano solo le faltan 1-3 Macabeos y al Sinaítico le faltan 2-3 Macabeos,1 Esdras , Baruc y Carta de Jeremías . [38] Junto con la Peshitta y el Codex Alexandrinus , estas son las primeras Biblias cristianas existentes. [39]

No hay evidencia entre los cánones del Primer Concilio de Nicea de alguna determinación sobre el canon , sin embargo, Jerónimo (347-420), en su Prólogo a Judith , afirma que el Libro de Judith fue "encontrado por el Concilio de Nicea haber sido contado entre el número de las Sagradas Escrituras ". [40]

Cánones orientales

Las iglesias orientales tenían, en general, un sentimiento más débil que las occidentales por la necesidad de hacer delineamientos precisos con respecto al canon. Eran más conscientes de la gradación de la calidad espiritual entre los libros que aceptaban (por ejemplo, la clasificación de Eusebio, véase también Antilegomena ) y estaban menos dispuestos a afirmar que los libros que rechazaban no poseían ninguna calidad espiritual. Por ejemplo, el Sínodo de Trullan de 691-692 , que el Papa Sergio I (en el cargo 687-701) rechazó [41] (ver también Pentarquía ), aprobó las siguientes listas de escritos canónicos: los Cánones Apostólicos (c. 385), el Sínodo de Laodicea(c. 363), el Tercer Sínodo de Cartago (c. 397) y la 39ª Carta Festal de Atanasio (367). [42] Y, sin embargo, estas listas no concuerdan. De manera similar, los cánones del Nuevo Testamento de las iglesias siríaca , armenia , georgiana , copta egipcia y etíope tienen diferencias menores, sin embargo, cinco de estas iglesias son parte de la misma comunión y tienen las mismas creencias teológicas. [43] La revelación de Juanse dice que es uno de los libros más inciertos; no se tradujo al georgiano hasta el siglo X, y nunca se ha incluido en el leccionario oficial de la Iglesia Ortodoxa Oriental , ni en la época bizantina ni en la moderna.

Peshitta

La Peshitta es la versión estándar de la Biblia para las iglesias de tradición siríaca . La mayoría de los libros deuterocanónicos del Antiguo Testamento se encuentran en siríaco, y se cree que la Sabiduría de Sirac ha sido traducida del hebreo y no de la Septuaginta . [44] Este Nuevo Testamento, que originalmente excluía ciertos libros en disputa (2 Pedro, 2 Juan, 3 Juan, Judas, Apocalipsis), se había convertido en un estándar a principios del siglo quinto. Los cinco libros excluidos se agregaron en la versión de Harklean (616 d.C.) de Tomás de Harqel . [45]

La edición estándar de 1905 de las Sociedades Bíblicas Unidas del Nuevo Testamento de la Peshitta se basó en ediciones preparadas por los siríacos Philip E. Pusey (muerto en 1880), George Gwilliam (muerto en 1914) y John Gwyn . [46] Los veintisiete libros del Nuevo Testamento occidental común están incluidos en la edición Peshitta de 1905 de esta Sociedad Bíblica Británica y Extranjera.

Iglesia occidental

Padres latinos

El primer Concilio que aceptó el canon católico actual (el Canon de Trento de 1546) pudo haber sido el Sínodo de Hippo Regius , celebrado en el norte de África en 393. Un breve resumen de los actos fue leído y aceptado por el Concilio de Cartago ( 397) y también el Concilio de Cartago (419) . [47] Estos Concilios se llevaron a cabo bajo la autoridad de San Agustín (354-430), quien consideró el canon como ya cerrado. [48] Sus decretos también declararon por decreto que la Epístola a los Hebreos fue escrita por Pablo, por un tiempo poniendo fin a todo debate sobre el tema.

Agustín de Hipona declaró sin reservas que hay que "preferir las que son recibidas por todas las Iglesias católicas a las que algunas de ellas no reciben" (Sobre las doctrinas cristianas 2.12). En el mismo pasaje, Agustín afirmó que estas iglesias disidentes deberían ser superadas por las opiniones de "las iglesias más numerosas y de mayor peso", que incluirían las Iglesias orientales, cuyo prestigio afirmó Agustín lo movió a incluir el Libro de Hebreos entre los canónicos. escritos, aunque tenía reservas sobre su autoría. [49]

Philip Schaff dice que "el concilio de Hipona en 393, y el tercero (según otro cálculo del sexto) concilio de Cartago en 397, bajo la influencia de Agustín, quien asistió a ambos, fijó el canon católico de las Sagradas Escrituras, incluido el Apócrifos del Antiguo Testamento ... Sin embargo, esta decisión de la iglesia transmarina estaba sujeta a ratificación; y la concurrencia de la sede romana la recibió cuando Inocencio I y Gelasio I (414 d.C.) repitieron el mismo índice de libros bíblicos. el canon permaneció inalterado hasta el siglo XVI, y fue sancionado por el concilio de Trento en su cuarta sesión ". [50] Según Lee Martin McDonald, la Revelaciónfue agregado a la lista en 419. [47] Estos concilios fueron convocados bajo la influencia de San Agustín , quien consideró el canon como ya cerrado. [51] [52] [53]

El Concilio de Roma del Papa Dámaso I en 382 (si el Decretum emitió un canon bíblico idéntico al mencionado anteriormente). [35] Asimismo, el encargo de Dámaso de la edición Vulgata Latina de la Biblia, c. 383, resultó fundamental en la fijación del canon en Occidente. [54]

En una carta ( c. 405) a Exsuperius de Toulouse , un obispo galo, el Papa Inocencio mencioné los libros sagrados que ya se recibieron en el canon. [55] Cuando los obispos y concilios hablaron sobre el canon bíblico, sin embargo, no estaban definiendo algo nuevo, sino que "estaban ratificando lo que ya se había convertido en la mente de la Iglesia". [56] Así, desde el siglo IV existió unanimidad en Occidente con respecto al canon del Nuevo Testamento como es hoy, [57] con la excepción del Libro de Apocalipsis . En el siglo V Orientetambién, con unas pocas excepciones, llegó a aceptar el Libro del Apocalipsis y así entró en armonía en el tema del canon del Nuevo Testamento. [58]

A medida que el canon cristalizó, los textos no canónicos cayeron en un relativo desamor y descuido. [59]

Era de la reforma

Antes de la Reforma Protestante , tuvo lugar el Concilio de Florencia (1439-1443). Con la aprobación de este concilio ecuménico , el Papa Eugenio IV (en el cargo 1431-1447) emitió varias bulas ( decretos ) papales con miras a restaurar las iglesias orientales , que la Iglesia católica consideraba como cuerpos cismáticos , en comunión con Roma . Los teólogos católicos consideran estos documentos como declaraciones infalibles de la doctrina católica . El Decretum pro Jacobitiscontiene una lista completa de los libros recibidos por la Iglesia Católica como inspirados, pero omite los términos "canon" y "canonical". Por lo tanto, el Concilio de Florencia enseñó la inspiración de todas las Escrituras, pero no se pronunció formalmente sobre la canonicidad. [60] [61]

Solo en el siglo XVI, cuando los reformadores protestantes comenzaron a insistir en la autoridad suprema de las escrituras (la doctrina de la sola scriptura ), se hizo más importante para Roma establecer un canon dogmático definitivo, [ cita requerida ] que el Concilio de Trento adoptado en 1546.

Canon y apócrifos de Lutero

Martín Lutero (1483-1546) movió siete libros del Antiguo Testamento (Tobit, Judith, 1-2 Macabeos, Libro de la Sabiduría, Eclesiástico y Baruc) en una sección que llamó " Apócrifos , que son libros que no se consideran iguales a los Sagradas Escrituras, pero son útiles y de buena lectura ". [62] Debido a que la palabra "apócrifos" ya se refería a escritos cristianos antiguos que la Iglesia Católica no incluyó en su canon establecido, el término deuterocanónico fue adoptado en el Concilio de Trento (1545-1563) para referirse a aquellos libros que Lutero movió en la sección apócrifa de su Biblia.

Lutero eliminó los libros de Hebreos, Santiago, Judas y Apocalipsis del canon en parte porque se percibía que algunos iban en contra de ciertas doctrinas protestantes como sola scriptura y sola fide ), [63] [ verificación fallida ] mientras que los defensores de Lutero citan precedentes académicos previos y apoyo como justificación para su marginación de ciertos libros, [64] incluyendo 2 Macabeos [65] El canon más pequeño de Lutero no fue completamente aceptado en el protestantismo, aunque los libros apócrifos se ordenan en último lugar en la Biblia de Lutero en idioma alemán hasta el día de hoy.

Todos estos apócrifos son llamados anagignoskomena por los ortodoxos orientales según el Sínodo de Jerusalén .

Al igual que con las iglesias luteranas , [66] la Comunión Anglicana acepta "los apócrifos para la instrucción en la vida y los modales, pero no para el establecimiento de la doctrina", [67] y muchas "lecturas del leccionario en el Libro de Oración Común se toman del Apócrifos ", con estas lecciones" leídas de la misma manera que las del Antiguo Testamento ". [68] El Protestant Apocrypha contiene tres libros (3 Esdras, 4 Esdras y la Oración de Manasseh) que son aceptados por muchas Iglesias Ortodoxas Orientales y Iglesias Ortodoxas Orientales como canónicos, pero son considerados no canónicos por la Iglesia Católica y por lo tanto son no incluido en las Biblias católicas modernas. [69]

Los anabautistas usan la Biblia de Lutero , que contiene los libros intertestamentarios; Las ceremonias de boda amish incluyen "el recuento del matrimonio de Tobías y Sarah en los Apócrifos". [70] Los padres del anabautismo, como Menno Simmons , los citaron "[los apócrifos] con la misma autoridad y casi con la misma frecuencia que los libros de la Biblia hebrea" y los textos relacionados con los mártires bajo Antíoco IV en 1 Macabeos y 2 Los anabautistas tienen en alta estima a los macabeos , quienes históricamente enfrentaron persecución en su historia. [71]

Los leccionarios luteranos y anglicanos continúan incluyendo lecturas de los apócrifos. [72]

Concilio de Trento

En respuesta a las demandas de Martín Lutero , el Concilio de Trento del 8 de abril de 1546 aprobó el actual canon bíblico católico , que incluye los libros deuterocanónicos , y la decisión fue confirmada por un anatema por voto (24 sí, 15 no, 16 abstenciones). . [73] El concilio confirma la misma lista que se produjo en el Concilio de Florencia en 1442, [74] los 397-419 Concilios de Cartago de Agustín , [50] y probablemente el 382 Concilio de Roma de Dámaso . [35] [75]Los libros del Antiguo Testamento que habían sido rechazados por Lutero se denominaron más tarde "deuterocanónicos", lo que no indica un grado menor de inspiración, sino un tiempo posterior de aprobación final. La Vulgata Sixto-Clementina contenía en el Apéndice varios libros considerados apócrifos por el concilio: Oración de Manasés , 3 Esdras y 4 Esdras . [76]

Confesiones protestantes

Varias confesiones de fe protestantes identifican los 27 libros del canon del Nuevo Testamento por su nombre, incluida la Confesión de fe francesa (1559), [77] la Confesión belga (1561) y la Confesión de fe de Westminster (1647). La Segunda Confesión Helvética (1562), afirma que "ambos testamentos es la verdadera Palabra de Dios" y apelando a Agustín 's De Civitate Dei , que rechazó la canonicidad de los libros apócrifos. [78] Los Treinta y Nueve Artículos , publicados por la Iglesia de Inglaterra en 1563, nombran los libros del Antiguo Testamento, pero no el Nuevo Testamento. La confesión belga [79]y la Confesión de Westminster nombraron los 39 libros del Antiguo Testamento y, aparte de los libros del Nuevo Testamento antes mencionados, rechazaron expresamente la canonicidad de cualquier otro. [80]

El Epítome Luterano de la Fórmula de Concordia de 1577 declaró que las Escrituras proféticas y apostólicas comprendían solo el Antiguo y el Nuevo Testamento. [81] El mismo Lutero no aceptó la canonicidad de los apócrifos aunque creía que sus libros "no eran iguales a las Escrituras, pero son útiles y buenos para leer". [82] Los leccionarios luteranos y anglicanos continúan incluyendo lecturas de los apócrifos. [72]

Otros apócrifos

Varios libros que nunca fueron canonizados por ninguna iglesia, pero que se sabe que existieron en la antigüedad, son similares al Nuevo Testamento y a menudo reclaman la autoría apostólica, se conocen como los apócrifos del Nuevo Testamento . Algunos de estos escritos han sido citados como escritura por los primeros cristianos, pero desde el siglo V ha surgido un consenso generalizado que limita el Nuevo Testamento a los 27 libros del canon moderno . [83] [84] Por lo tanto, las iglesias católica romana, ortodoxa oriental y protestante generalmente no ven estos apócrifos del Nuevo Testamento como parte de la Biblia. [84]

Cánones de diversas tradiciones

Las articulaciones dogmáticas finales de los cánones se hicieron en el Concilio de Trento de 1546 para el catolicismo romano, [85] los Treinta y Nueve Artículos de 1563 para la Iglesia de Inglaterra , la Confesión de Fe de Westminster de 1647 para el Calvinismo y el Sínodo de Jerusalén. de 1672 para los ortodoxos orientales . Otras tradiciones, aunque también tienen cánones cerrados, es posible que no puedan señalar un año exacto en el que se completaron sus cánones. Las siguientes tablas reflejan el estado actual de varios cánones cristianos.

Antiguo Testamento

La Iglesia Primitiva usó principalmente la Septuaginta griega (o LXX) como fuente del Antiguo Testamento. Entre los hablantes de arameo , el Targum también se utilizó ampliamente. Todas las principales tradiciones cristianas aceptan los libros del protocanon hebreo en su totalidad como de inspiración divina y con autoridad, de diversas maneras y grados.

Otro conjunto de libros, escritos en gran parte durante el período intertestamental , son llamados apócrifos bíblicos ("cosas ocultas") por los protestantes, el deuterocanon ("segundo canon") por los católicos y el deuterocanon o anagignoskomena ("digno de lectura") por Ortodoxo. Estas son obras reconocidas por las iglesias católica, ortodoxa oriental y ortodoxa oriental como parte de las escrituras (y, por lo tanto, deuterocanónicas en lugar de apócrifas), pero los protestantes no las reconocen como de inspiración divina . Algunas Biblias protestantes, especialmente la Biblia King James en inglés y la Biblia luterana, incluyen una sección "Apócrifa".

Muchas denominaciones reconocen los libros deuterocanónicos como buenos, pero no al nivel de los otros libros de la Biblia. El anglicanismo considera los apócrifos dignos de ser "leídos por ejemplo de la vida" pero no para ser utilizados "para establecer ninguna doctrina". [86] Lutero hizo una declaración paralela al llamarlos: "no se consideran iguales a las Sagradas Escrituras, pero ... útiles y de buena lectura". [87]

La diferencia en los cánones se deriva de la diferencia en el Texto Masorético y la Septuaginta . Los libros que se encuentran tanto en hebreo como en griego son aceptados por todas las denominaciones, y para los judíos, estos son los libros protocanónicos. Los católicos y ortodoxos también aceptan aquellos libros presentes en los manuscritos de la Septuaginta, una antigua traducción griega del Antiguo Testamento con gran vigencia entre los judíos del mundo antiguo, con la coda que los católicos consideran apócrifos 3 Esdras y 3 Macabeos . [ cita requerida ]

Daniel fue escrito varios cientos de años después de la época de Esdras, y desde entonces se han encontrado varios libros de la Septuaginta en el hebreo original, en los Rollos del Mar Muerto , la Geniza de El Cairo y en Masada , incluido un texto hebreo de Siraj ( Qumran, Masada) y un texto arameo de Tobit (Qumran); las adiciones a Esther y Daniel también están en sus respectivos idiomas semíticos. [ cita requerida ]

En el canon ortodoxo oriental de Tewahedo , los libros de Lamentaciones , Jeremías y Baruc, así como la Carta de Jeremías y 4 Baruch , son todos considerados canónicos por las Iglesias ortodoxas de Tewahedo. Sin embargo, no siempre está claro cómo se organizan o dividen estos escritos. En algunas listas, simplemente pueden caer bajo el título "Jeremías", mientras que en otras, se dividen de varias maneras en libros separados. Además, el libro de Proverbios se divide en dos libros: Messale (Prov. 1-24) y Tägsas (Prov. 25-31).

Además, mientras que los libros de Jubileos y Enoch son bastante conocidos entre los eruditos occidentales, 1, 2 y 3 Meqabyan no lo son. Los tres libros de Meqabyan a menudo se llaman los "Macabeos etíopes", pero son completamente diferentes en contenido de los libros de Macabeos que se conocen o han sido canonizados en otras tradiciones. Finalmente, el Libro de Joseph ben Gurion, o Pseudo-Josefo , es una historia del pueblo judío que se cree está basada en los escritos de Josefo . [nota 3] La versión etíope (Zëna Ayhud) tiene ocho partes y está incluida en el canon más amplio ortodoxo Tewahedo . [nota 4] [88]

Libros adicionales aceptados por la Iglesia Ortodoxa Siria (debido a su inclusión en la Peshitta ):

- 2 Baruc con la Carta de Baruch (solo la carta ha alcanzado el estatus canónico)

- Salmos 152-155 (no canónico)

La iglesia etíope de Tewahedo acepta todos los libros deuterocanónicos del catolicismo y anagignoskomena de la ortodoxia oriental, excepto los cuatro libros de los Macabeos. [89] Acepta los 39 libros protocanónicos junto con los siguientes libros, llamados " canon estrecho ". [90] La enumeración de libros en la Biblia etíope varía mucho entre las diferentes autoridades e impresiones. [91]

- 4 Baruc o el Paralipomena de Jeremías

- 1 Enoc

- Jubileos

- Primer, segundo y tercer libro de los macabeos etíopes

- El canon bíblico más amplio de Etiopía

Protestantes y católicos [6] utilizan el Texto Masorético del Tanaj judío como base textual para sus traducciones de los libros protocanónicos (aquellos aceptados como canónicos tanto por judíos como por todos los cristianos), con varios cambios derivados de una multiplicidad de otras fuentes antiguas ( como la Septuaginta , la Vulgata , los Rollos del Mar Muerto , etc.), mientras que generalmente usa la Septuaginta y la Vulgata, ahora complementadas por los antiguos manuscritos hebreos y arameos, como base textual para los libros deuterocanónicos .

Los ortodoxos orientales usan la Septuaginta (traducida en el siglo III a. C.) como la base textual de todo el Antiguo Testamento tanto en libros protocanónicos como deuteroncanónicos, para usarlos en griego con fines litúrgicos y como base para las traducciones a la lengua vernácula . [92] [93] La mayoría de las citas (300 de 400) del Antiguo Testamento en el Nuevo Testamento, aunque difieren más o menos de la versión presentada por el texto masorético, se alinean con la de la Septuaginta. [94]

Diagrama del desarrollo del Antiguo Testamento

Mesa

El orden de algunos libros varía según los cánones.

| Tradición occidental | Tradición ortodoxa oriental | Tradición ortodoxa oriental | Tradición de la Iglesia de Oriente | judaísmo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Libros | Protestante inconformista [O 1] | luterano | anglicano | Católico romano [95] [O 2] | ortodoxo griego | Ortodoxo eslavo | Ortodoxo georgiano | Apostólico armenio [O 3] | Siríaco ortodoxo | Copto ortodoxo | Tewahedo ortodoxo [96] [O 4] | Iglesia asiria de Oriente | la Biblia hebrea |

| Pentateuco | Tora | ||||||||||||

| Génesis | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si Bereshit |

| éxodo | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si Shemot |

| Levíticio | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si Vayikra |

| Números | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Bemidbar |

| Deuteronomio | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si Devarim |

| Historia | Nevi'im | ||||||||||||

| Joshua | sí | sí | sí | Si Josue | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si Yehoshua |

| Jueces | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Shofetim |

| Piedad | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Rut (parte de Ketuvim) |

| 1 y 2 Samuel | sí | sí | sí | Si 1 y 2 Reyes | Si 1 y 2 Reinos | Si 1 y 2 Reinos | Si 1 y 2 Reinos | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si Shemuel |

| 1 y 2 reyes | sí | sí | sí | Si 3 y 4 Reyes | Si 3 y 4 Reinos | Si 3 y 4 Reinos | Si 3 y 4 Reinos | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Melakhim |

| 1 y 2 Crónicas | sí | sí | sí | Sí 1 y 2 Paraíso | Sí 1 y 2 Paraíso | Sí 1 y 2 Paraíso | Sí 1 y 2 Paraíso | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Divrei Hayamim (parte de Ketuvim) |

| Oración de Manasés | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) [O 5] | No (apócrifos) [O 5] | No - inc. en algunos mss. | Sí (?) (Parte de Odas) [O 6] | Sí (?) (Parte de Odas) [O 6] | Sí (?) (Parte de Odas) [O 6] | Sí (?) | Sí (?) | Sí [97] | Sí [98] | Sí (?) | No |

| Esdras (1 Esdras) | sí | sí | sí | Sí 1 Esdras | Sí Esdras B ' | Sí 1 Esdras | Sí 1 Ezra | Sí 1 Ezra | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí, Ezra – Nehemiah (parte de Ketuvim) |

| Nehemías (2 Esdras) | sí | sí | sí | Sí 2 Esdras | Sí Esdras Γ 'o Neemias | Si Neemias | Si Neemias | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | |

| 1 Esdras (3 Esdras) | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No | No 1 Esdras (Apócrifos) | No 3 Esdras (incluido en algunos manuscritos) [99] | Sí Esdras A ' | Sí 2 Esdras | Sí 2 Ezra | Sí 2 Esdras [O 7] | No (?) - inc. en algunos mss. | No - inc. en algunos mss. | Sí, Ezra Kali | No (?) - inc. en algunos mss. | No |

| 2 Esdras 3-14 (4 Esdras o Apocalipsis de Esdras) [O 8] | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No | No 2 Esdras (Apócrifos) | No 4 Esdras (inc. En algunos mss.) | No (griego ms. Perdido) [O 9] | No 3 Esdras (apéndice) | Sí (?) 3 Ezra | Sí 3 Esdras [O 7] | No (?) - inc. en algunos mss. | No - inc. en algunos mss. | Sí, Ezra Sutu'el | No (?) - inc. en algunos mss. | No |

| 2 Esdras 1–2; 15-16 (5 y 6 Esdras o Apocalipsis de Esdras) [O 8] | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No | No (parte del apócrifo de 2 Esdras) | No (parte de 4 Esdras) | No (ms griego) [O 10] | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Esther [O 11] | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Ester (parte de Ketuvim) |

| Adiciones a Esther | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | No |

| Tobit (Tobías) | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | No |

| Judith | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | No |

| 1 Macabeos [O 12] | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | Si 1 Macabeos | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | No | sí | No |

| 2 Macabeos [O 12] | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | Si 2 Macabeos | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | No | sí | No |

| 3 macabeos | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No | sí | sí | sí | Sí [O 7] | sí | No - inc. en algunos mss. | No | sí | No |

| 4 macabeos | No | No | No | No | No (apéndice) | No (apéndice) | sí | No (tradición temprana) | No (?) - inc. en algunos mss. | No (señora copta) | No | No (?) - inc. en algunos mss. | No |

| Jubileos | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | sí | No | No |

| Enoc | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | sí | No | No |

| 1 Macabeos etíopes (1 Meqabyan) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | sí | No | No |

| 2 y 3 Macabeos etíopes [O 13] (2 y 3 Meqabyan) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | sí | No | No |

| Pseudo-Josefo etíope (Zëna Ayhud) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sí (canon más amplio) [O 14] | No | No |

| La VI Guerra Judía de Josefo | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No - inc. en algunos mss. [O 15] | No | No | No - inc. en algunos mss. [O 15] | No |

| Testamentos de los Doce Patriarcas | No | No | No | No | No (griego ms.) | No | No | No - inc. en algunos mss. | No | No | No | No | No |

| José y Asenath | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No - inc. en algunos mss. | No | No | No (¿tradición antigua?) [O 16] | No | No |

| Sabiduría | Ketuvim | ||||||||||||

| Libro de Job | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si Iyov |

| Salmos 1–150 [O 17] | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Tehillim |

| Salmo 151 | No | No | No | No - inc. en algunos mss. | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | No |

| Salmos 152-155 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sí (?) | No | No | No (?) - inc. en algunos mss. | No |

| Salmos de Salomón [O 18] | No | No | No | No | No - inc. en algunos mss. | No | No | No | No - inc. en algunos mss. | No | No | No - inc. en algunos mss. | No |

| Proverbios | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si (en 2 libros) | sí | Sí Mishlei |

| Eclesiastés | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Qohelet |

| Canción de canciones | sí | sí | sí | Sí, cántico de los cánticos | Sí Aisma Aismaton | Sí Aisma Aismaton | Sí Aisma Aismaton | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Shir Hashirim |

| Libro de Sabiduría o Sabiduría de Salomón | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | No |

| Sabiduría de Eclesiástico o Eclesiástico (1–51) [O 19] | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | Sí [O 20] Eclesiástico | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | No |

| Oración de Salomón (Eclesiástico 52) [O 21] | No | No | No | No (?) - inc. en algunos mss. | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Profetas mayores | Nevi'im | ||||||||||||

| Isaías | sí | sí | sí | Si Isaias | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Si Yeshayahu |

| Ascensión de Isaías | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No - litúrgico (?) [O 22] | No | No | No - mss etíope. (¿tradición antigua?) [O 23] | No | No |

| Jeremías | sí | sí | sí | Si Jeremias | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí Yirmeyahu |

| Lamentaciones (1–5) | sí | sí | sí | Sí [O 24] | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí (parte de Säqoqawä Eremyas ) [O 25] | sí | Sí Eikhah (parte de Ketuvim) |

| Lamentaciones etíopes (6; 7: 1–11,63) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sí (parte de Säqoqawä Eremyas) [O 25] | No | No |

| Baruch | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí [O 26] [O 27] | sí | No |

| Carta de Jeremías | No - inc. en algunos eds. | No (apócrifos) | No (apócrifos) | Sí (capítulo 6 de Baruc) | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | sí | Sí (parte de Säqoqawä Eremyas) [O 28] [O 25] [O 27] | sí | No |

| Apocalipsis siríaco de Baruc ( 2 Baruc 1-77) [O 29] | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Sí (?) | No | No | No (?) – inc. in some mss. | No |

| Letter of Baruch (2 Baruch 78–87)[O 29] | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (?) | No | No | Yes (?) | No |

| Greek Apocalypse of Baruch (3 Baruch)[O 30] | No | No | No | No | No (Greek ms.) | No (Slavonic ms.) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 4 Baruch | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (part of Säqoqawä Eremyas) | No | No |

| Ezekiel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Ezechiel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Yekhezqel |

| Daniel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Daniyyel (part of Ketuvim) |

| Additions to Daniel[O 31] | No − inc. in some eds. | No (Apocrypha) | No (Apocrypha) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Twelve Minor Prophets | Trei Asar | ||||||||||||

| Hosea | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Osee | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Joel | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Amos | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Obadiah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Abdias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jonah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Jonas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Micah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Micheas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nahum | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Habakkuk | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Habacuc | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zephaniah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Sophonias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Haggai | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Aggeus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Zechariah | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Zacharias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Malachi | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes Malachias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table notes

The table uses the spellings and names present in modern editions of the Bible, such as the New American Bible Revised Edition, Revised Standard Version and English Standard Version. The spelling and names in both the 1609–1610 Douay Old Testament (and in the 1582 Rheims New Testament) and the 1749 revision by Bishop Challoner (the edition currently in print used by many Catholics, and the source of traditional Catholic spellings in English) and in the Septuagint differ from those spellings and names used in modern editions that derive from the Hebrew Masoretic text.[100]

The King James Version references some of these books by the traditional spelling when referring to them in the New Testament, such as "Esaias" (for Isaiah). In the spirit of ecumenism more recent Catholic translations (e.g., the New American Bible, Jerusalem Bible, and ecumenical translations used by Catholics, such as the Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition) use the same "standardized" (King James Version) spellings and names as Protestant Bibles (e.g., 1 Chronicles, as opposed to the Douaic 1 Paralipomenon, 1–2 Samuel and 1–2 Kings, instead of 1–4 Kings) in the protocanonicals.

The Talmud in Bava Batra 14b gives a different order for the books in Nevi'im and Ketuvim. This order is also quoted in Mishneh Torah Hilchot Sefer Torah 7:15. The order of the books of the Torah are universal through all denominations of Judaism and Christianity.

- ^ The term "Protestant" is not accepted by all Christian denominations who often fall under this title by default—especially those who view themselves as a direct extension of the New Testament church. However, the term is used loosely here to include, with the exception of Lutherans and Anglicans, most of the non-Roman Catholic Protestant, Charismatic/Pentecostal, Reformed, and Evangelical churches. Other western churches and movements that have a divergent history from Roman Catholicism, but are not necessarily considered to be historically Protestant, may also fall under this umbrella terminology.

- ^ The Roman Catholic Canon as represented in this table reflects the Latin tradition. Some Eastern Rite churches who are in fellowship with the Roman Catholic Church may have different books in their canons.

- ^ The growth and development of the Armenian Biblical canon is complex. Extra-canonical Old Testament books appear in historical canon lists and recensions that are either exclusive to this tradition, or where they do exist elsewhere, never achieved the same status. These include the Deaths of the Prophets, an ancient account of the lives of the Old Testament prophets, which is not listed in this table. (It is also known as the Lives of the Prophets.) Another writing not listed in this table entitled the Words of Sirach—which is distinct from Ecclesiasticus and its prologue—appears in the appendix of the 1805 Armenian Zohrab Bible alongside other, more commonly known works.

- ^ Adding to the complexity of the Orthodox Tewahedo Biblical canon, the national epic Kebra Negast has an elevated status among many Ethiopian Christians to such an extent that some consider it to be inspired scripture.

- ^ a b The English Apocrypha includes the Prayer of Manasseh, 1 & 2 Esdras, the Additions to Esther, Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, the Book of Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, the Letter of Jeremiah, and the Additions to Daniel. The Lutheran Apocrypha omits from this list 1 & 2 Esdras. Some Protestant Bibles include 3 Maccabees as part of the Apocrypha. However, many churches within Protestantism—as it is presented here—reject the Apocrypha, do not consider it useful, and do not include it in their Bibles.

- ^ a b c The Prayer of Manasseh is included as part of the Book of Odes, which follows the Psalms in Eastern Orthodox Bibles. The rest of the Book of Odes consists of passages found elsewhere in the Bible. It may also be found at the end of 2 Chronicles (2 Paralipomenon)

- ^ a b c 2 Ezra, 3 Ezra, and 3 Maccabees are included in Bibles and have an elevated status within the Armenian scriptural tradition, but are considered "extra-canonical".

- ^ a b In many eastern Bibles, the Apocalypse of Ezra is not an exact match to the longer Latin Esdras–2 Esdras in KJV or 4 Esdras in the Vulgate—which includes a Latin prologue (5 Ezra) and epilogue (6 Ezra). However, a degree of uncertainty continues to exist here, and it is certainly possible that the full text—including the prologue and epilogue—appears in Bibles and Biblical manuscripts used by some of these eastern traditions. Also of note is the fact that many Latin versions are missing verses 7:36–7:106. (A more complete explanation of the various divisions of books associated with the scribe Ezra may be found in the Wikipedia article entitled "Esdras".)

- ^ Evidence strongly suggests that a Greek manuscript of 4 Ezra once existed; this furthermore implies a Hebrew origin for the text.

- ^ An early fragment of 6 Ezra is known to exist in the Greek language, implying a possible Hebrew origin for 2 Esdras 15–16.

- ^ Esther's placement within the canon was questioned by Luther. Others, like Melito, omitted it from the canon altogether.

- ^ a b The Latin Vulgate, Douay–Rheims, and Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition place First and Second Maccabees after Malachi; other Catholic translations place them after Esther.

- ^ 2 and 3 Meqabyan, though relatively unrelated in content, are often counted as a single book.

- ^ Some sources place Zëna Ayhud within the "narrower canon".

- ^ a b A Syriac version of Josephus's Jewish War VI appears in some Peshitta manuscripts as the "Fifth Book of Maccabees", which is clearly a misnomer.

- ^ Several varying historical canon lists exist for the Orthodox Tewahedo tradition. In one particular list Archived 10 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine found in a British Museum manuscript (Add. 16188), a book of Assenath is placed within the canon. This most likely refers to the book more commonly known as Joseph and Asenath. An unknown book of Uzziah is also listed there, which may be connected to the lost Acts of Uziah referenced in 2 Chronicles 26:22.

- ^ Some traditions use an alternative set of liturgical or metrical Psalms.

- ^ In many ancient manuscripts, a distinct collection known as the Odes of Solomon is found together with the similar Psalms of Solomon.

- ^ The book of Sirach is usually preceded by a non-canonical prologue written by the author's grandson.

- ^ In some Latin versions, chapter 51 of Ecclesiasticus appears separately as the "Prayer of Joshua, son of Sirach".

- ^ A shorter variant of the prayer by King Solomon in 1 Kings 8:22–52 appeared in some medieval Latin manuscripts and is found in some Latin Bibles at the end of or immediately following Ecclesiasticus. The two versions of the prayer in Latin may be viewed online for comparison at the following website: BibleGateway.com: Sirach 52 / 1 Kings 8:22–52; Vulgate

- ^ The "Martyrdom of Isaiah" is prescribed reading to honor the prophet Isaiah within the Armenian Apostolic liturgy (see this list). While this likely refers to the account of Isaiah's death within the Lives of the Prophets, it may be a reference to the account of his death found within the first five chapters of the Ascension of Isaiah, which is widely known by this name. The two narratives have similarities and may share a common source.

- ^ The Ascension of Isaiah has long been known to be a part of the Orthodox Tewahedo scriptural tradition. Though it is not currently considered canonical, various sources attest to the early canonicity—or at least "semi-canonicity"—of this book.

- ^ In some Latin versions, chapter 5 of Lamentations appears separately as the "Prayer of Jeremiah".

- ^ a b c Ethiopic Lamentations consists of eleven chapters, parts of which are considered to be non-canonical.

- ^ The canonical Ethiopic version of Baruch has five chapters, but is shorter than the LXX text.

- ^ a b Some Ethiopic translations of Baruch may include the traditional Letter of Jeremiah as the sixth chapter.

- ^ The "Letter to the Captives" found within Säqoqawä Eremyas—and also known as the sixth chapter of Ethiopic Lamentations—may contain different content from the Letter of Jeremiah (to those same captives) found in other traditions.

- ^ a b The Letter of Baruch is found in chapters 78–87 of 2 Baruch—the final ten chapters of the book. The letter had a wider circulation and often appeared separately from the first 77 chapters of the book, which is an apocalypse.

- ^ Included here for the purpose of disambiguation, 3 Baruch is widely rejected as a pseudepigraphon and is not part of any Biblical tradition. Two manuscripts exist—a longer Greek manuscript with Christian interpolations and a shorter Slavonic version. There is some uncertainty about which was written first.

- ^ Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, and The Prayer of Azariah and Song of the Three Holy Children.

New Testament

Among the various Christian denominations, the New Testament canon is a generally agreed-upon list of 27 books. However, the way in which those books are arranged may vary from tradition to tradition. For instance, in the Slavonic, Orthodox Tewahedo, Syriac, and Armenian traditions, the New Testament is ordered differently from what is considered to be the standard arrangement. Protestant Bibles in Russia and Ethiopia usually follow the local Orthodox order for the New Testament. The Syriac Orthodox Church and the Assyrian Church of the East both adhere to the Peshitta liturgical tradition, which historically excludes five books of the New Testament Antilegomena: 2 John, 3 John, 2 Peter, Jude, and Revelation. However, those books are included in certain Bibles of the modern Syriac traditions.

Other New Testament works that are generally considered apocryphal nonetheless appear in some Bibles and manuscripts. For instance, the Epistle to the Laodiceans[note 5] was included in numerous Latin Vulgate manuscripts, in the eighteen German Bibles prior to Luther's translation, and also a number of early English Bibles, such as Gundulf's Bible and John Wycliffe's English translation—even as recently as 1728, William Whiston considered this epistle to be genuinely Pauline. Likewise, the Third Epistle to the Corinthians[note 6] was once considered to be part of the Armenian Orthodox Bible,[101] but is no longer printed in modern editions. Within the Syriac Orthodox tradition, the Third Epistle to the Corinthians also has a history of significance. Both Aphrahat and Ephraem of Syria held it in high regard and treated it as if it were canonical.[102] However, it was left-out of the Peshitta and ultimately excluded from the canon altogether.

The Didache,[note 7] The Shepherd of Hermas,[note 8] and other writings attributed to the Apostolic Fathers, were once considered scriptural by various early Church fathers. They are still being honored in some traditions, though they are no longer considered to be canonical. However, certain canonical books within the Orthodox Tewahedo traditions find their origin in the writings of the Apostolic Fathers as well as the Ancient Church Orders. The Orthodox Tewahedo churches recognize these eight additional New Testament books in its broader canon. They are as follows: the four books of Sinodos, the two books of the Covenant, Ethiopic Clement, and the Ethiopic Didascalia.[103]

Table

| Books | Protestant & Restoration traditions | Roman Catholic tradition | Eastern Orthodox tradition | Armenian Apostolic tradition[N 1] | Coptic Orthodox tradition | Orthodox Tewahedo traditions | Syriac Christian traditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical gospels[N 2] | |||||||

| Matthew | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 3] |

| Mark[N 4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 3] |

| Luke | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 3] |

| John[N 4][N 5] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 3] |

| Acts of apostles | |||||||

| Acts[N 4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Acts of Paul and Thecla[N 6][104][105] | No | No | No | No (early tradition) | No | No | No (early tradition) |

| Pauline epistles | |||||||

| Romans | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Corinthians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Corinthians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Corinthians to Paul and 3 Corinthians[N 6][N 7] | No | No | No | No − inc. in some mss. | No | No | No (early tradition) |

| Galatians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ephesians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Philippians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Colossians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Laodiceans | No − inc. in some eds.[N 8] | No − inc. in some mss. | No | No | No | No | No |

| 1 Thessalonians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Thessalonians | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Timothy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Timothy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Titus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Philemon | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Catholic epistles (General epistles) | |||||||

| Hebrews | Yes[N 9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| James | Yes[N 9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 1 Peter | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 Peter | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| 1 John[N 4] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 John | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| 3 John | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| Jude | Yes[N 9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| Apocalypse[N 11] | |||||||

| Revelation | Yes[N 9] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[N 10] |

| Apostolic Fathers[N 12] and Church Orders[N 13] | |||||||

| 1 Clement[N 14] | No (Codices Alexandrinus and Hierosolymitanus) | ||||||

| 2 Clement[N 14] | No (Codices Alexandrinus and Hierosolymitanus) | ||||||

| Shepherd of Hermas[N 14] | No (Codex Siniaticus) | ||||||

| Epistle of Barnabas[N 14] | No (Codices Hierosolymitanus and Siniaticus) | ||||||

| Didache[N 14] | No (Codex Hierosolymitanus) | ||||||

| Ser'atä Seyon (Sinodos) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Te'ezaz (Sinodos) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Gessew (Sinodos) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Abtelis (Sinodos) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Book of theCovenant 1 (Mäshafä Kidan) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Book of theCovenant 2 (Mäshafä Kidan) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Ethiopic Clement (Qälëmentos)[N 15] | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

| Ethiopic Didescalia (Didesqelya)[N 15] | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (broader canon) | No |

Table notes

- ^ The growth and development of the Armenian Biblical canon is complex. Extra-canonical New Testament books appear in historical canon lists and recensions that are either distinct to this tradition, or where they do exist elsewhere, never achieved the same status. Some of the books are not listed in this table. These include the Prayer of Euthalius, the Repose of St. John the Evangelist, the Doctrine of Addai (some sources replace this with the Acts of Thaddeus), a reading from the Gospel of James (some sources replace this with the Apocryphon of James), the Second Apostolic Canons, the Words of Justus, Dionysius Aeropagite, the Acts of Peter (some sources replace this with the Preaching of Peter), and a Poem by Ghazar. (Various sources also mention undefined Armenian canonical additions to the Gospels of Mark and John, however, these may refer to the general additions—Mark 16:9–20 and John 7:53–8:11—discussed elsewhere in these notes.) A possible exception here to canonical exclusivity is the Second Apostolic Canons, which share a common source—the Apostolic Constitutions—with certain parts of the Orthodox Tewahedo New Testament broader canon. The correspondence between King Agbar and Jesus Christ, which is found in various forms—including within both the Doctrine of Addai and the Acts of Thaddeus—sometimes appears separately (see this list). It is noteworthy that the Prayer of Euthalius and the Repose of St. John the Evangelist appear in the appendix of the 1805 Armenian Zohrab Bible. However, some of the aforementioned books, though they are found within canon lists, have nonetheless never been discovered to be part of any Armenian Biblical manuscript.

- ^ Though widely regarded as non-canonical, the Gospel of James obtained early liturgical acceptance among some Eastern churches and remains a major source for many of Christendom's traditions related to Mary, the mother of Jesus.

- ^ a b c d The Diatessaron, Tatian's gospel harmony, became a standard text in some Syriac-speaking churches down to the 5th century, when it gave-way to the four separate gospels found in the Peshitta.

- ^ a b c d Parts of these four books are not found in the most reliable ancient sources; in some cases, are thought to be later additions; and have therefore not historically existed in every Biblical tradition. They are as follows: Mark 16:9–20, John 7:53–8:11, the Comma Johanneum, and portions of the Western version of Acts. To varying degrees, arguments for the authenticity of these passages—especially for the one from the Gospel of John—have occasionally been made.

- ^ Skeireins, a commentary on the Gospel of John in the Gothic language, was included in the Wulfila Bible. It exists today only in fragments.

- ^ a b The Acts of Paul and Thecla, the Epistle of the Corinthians to Paul, and the Third Epistle to the Corinthians are all portions of the greater Acts of Paul narrative, which is part of a stichometric catalogue of New Testament canon found in the Codex Claromontanus, but has survived only in fragments. Some of the content within these individual sections may have developed separately, however.

- ^ The Third Epistle to the Corinthians often appears with and is framed as a response to the Epistle of the Corinthians to Paul.

- ^ The Epistle to the Laodiceans is present in some western non-Roman Catholic translations and traditions. Especially of note is John Wycliffe's inclusion of the epistle in his English translation, and the Quakers' use of it to the point where they produced a translation and made pleas for its canonicity (Poole's Annotations, on Col. 4:16). The epistle is nonetheless widely rejected by the vast majority of Protestants.

- ^ a b c d These four works were questioned or "spoken against" by Martin Luther, and he changed the order of his New Testament to reflect this, but he did not leave them out, nor has any Lutheran body since. Traditional German Luther Bibles are still printed with the New Testament in this changed "Lutheran" order. The vast majority of Protestants embrace these four works as fully canonical.

- ^ a b c d e The Peshitta excludes 2 John, 3 John, 2 Peter, Jude, and Revelation, but certain Bibles of the modern Syriac traditions include later translations of those books. Still today, the official lectionary followed by the Syriac Orthodox Church and the Assyrian Church of the East, present lessons from only the twenty-two books of Peshitta, the version to which appeal is made for the settlement of doctrinal questions.

- ^ The Apocalypse of Peter, though not listed in this table, is mentioned in the Muratorian fragment and is part of a stichometric catalogue of New Testament canon found in the Codex Claromontanus. It was also held in high regard by Clement of Alexandria.

- ^ Other known writings of the Apostolic Fathers not listed in this table are as follows: the seven Epistles of Ignatius, the Epistle of Polycarp, the Martyrdom of Polycarp, the Epistle to Diognetus, the fragment of Quadratus of Athens, the fragments of Papias of Hierapolis, the Reliques of the Elders Preserved in Irenaeus, and the Apostles' Creed.

- ^ Though they are not listed in this table, the Apostolic Constitutions were considered canonical by some including Alexius Aristenus, John of Salisbury, and to a lesser extent, Grigor Tat'evatsi. They are even classified as part of the New Testament canon within the body of the Constitutions itself. Moreover, they are the source for a great deal of the content in the Orthodox Tewahedo broader canon.

- ^ a b c d e These five writings attributed to the Apostolic Fathers are not currently considered canonical in any Biblical tradition, though they are more highly regarded by some more than others. Nonetheless, their early authorship and inclusion in ancient Biblical codices, as well as their acceptance to varying degrees by various early authorities, requires them to be treated as foundational literature for Christianity as a whole.

- ^ a b Ethiopic Clement and the Ethiopic Didascalia are distinct from and should not be confused with other ecclesiastical documents known in the west by similar names.

Latter Day Saint canons

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The standard works are the four books that currently constitute the open scriptural canon of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church):

- The King James Version of the Bible[note 9] without the biblical apocrypha

- The Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ

- The Doctrine and Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- The Pearl of Great Price

The Pearl of Great Price contains five sections: "Selections from the Book of Moses", "The Book of Abraham", "Joseph Smith–Matthew", "Joseph Smith–History", and "The Articles of Faith". The Book of Moses and Joseph Smith–Matthew are portions of the Book of Genesis and the Gospel of Matthew (respectively) from the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible, also known as the Inspired Version of the Bible.

The manuscripts of the unfinished Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible (JST-LDS) state that "the Song of Solomon is not inspired scripture",[106] but it is still printed in every version of the King James Bible published by the church.

The standard works are printed and distributed by the LDS Church in a single binding called a "quadruple combination" or as a set of two books, with the Bible in one binding, and the other three books in a second binding called a "triple combination". Current editions of the standard works include a bible dictionary, photographs, maps and gazetteer, topical guide, index, footnotes, cross references, excerpts from the Joseph Smith Translation of the Bible, and other study aids.

See also

- Related to the Bible

- Biblical criticism

- Canon (fiction) – a concept inspired by Biblical canon

- Canonical criticism

- Jewish apocrypha

- List of Old Testament pseudepigrapha

- Non-canonical gospels include:

- Gospel of Barnabas

- Gospel of Bartholomew

- Gospel of Basilides

- Gospel of Thomas

- Pseudepigraph

- Non-canonical books referenced in the Bible

- Canons of other religions

- Islamic holy books

- Canonization of Islamic scripture

- Avesta or Zoroastrian scriptures

- Yazidi holy texts

- Hindu scriptures

- Sikh scriptures or Adi Granth aka Guru Granth Sahib

- Tripiṭaka or Buddhist canon

- Pāli Canon

- Mahayana Canons

- Chinese classics

- Thirteen Classics or Confucian canon

- Ruzang

- Daozang or Taoist canon

Notes

- ^ For a fuller discussion of issues regarding the canonicity of Enoch, see the Reception of Enoch in antiquity.

- ^ Because of the lack of solid information on this subject, the exclusion of Lamentations from the Ethiopian Jewish canon is not a certainty. Furthermore, some uncertainty remains concerning the exclusion of various smaller deuterocanonical writings from this canon including the Prayer of Manasseh, the traditional additions to Esther, the traditional additions to Daniel, Psalm 151, and portions of Säqoqawä Eremyas.

- ^ Josephus's The Jewish War and Antiquities of the Jews are highly regarded by Christians because they provide valuable insight into 1st century Judaism and early Christianity. Moreover, in Antiquities, Josephus made two extra-Biblical references to Jesus, which have played a crucial role in establishing him as a historical figure.

- ^ The Orthodox Tewahedo broader canon in its fullest form—which includes the narrower canon in its entirety, as well as nine additional books—is not known to exist at this time as one published compilation. Some books, though considered canonical, are nonetheless difficult to locate and are not even widely available in Ethiopia. While the narrower canon has indeed been published as one compilation, there may be no real emic distinction between the broader canon and the narrower canon, especially in so far as divine inspiration and scriptural authority are concerned. The idea of two such classifications may be nothing more than etic taxonomic conjecture.

- ^ A translation of the Epistle to the Laodiceans can be accessed online at the Internet Sacred Texts Archive.

- ^ The Third Epistle to the Corinthians can be found as a section within the Acts of Paul, which has survived only in fragments. A translation of the entire remaining Acts of Paul can be accessed online at Early Christian Writings.

- ^ Various translations of the Didache can be accessed online at Early Christian Writings.

- ^ A translation of the Shepherd of Hermas can be accessed online at the Internet Sacred Texts Archive.

- ^ The LDS Church uses the King James Version (KJV) in English-speaking countries; other versions are used in non-English speaking countries.

References

Citations

- ^ Ulrich, Eugene (2002). "The Notion and Definition of Canon". In McDonald, L. M.; Sanders, J. A. (eds.). The Canon Debate. Hendrickson Publishers. pp. 29, 34. Ulrich's article defines "canon]" as follows: "...the definitive list of inspired, authoritative books which constitute the recognized and accepted body of sacred scripture of a major religious group, that definitive list being the result of inclusive and exclusive decisions after a serious deliberation". It is further defined as follows: "...the definitive, closed list of the books that constitute the authentic contents of scripture."

- ^ Ulrich (2002), p. 28. "The term is late and Christian ... though the idea is Jewish".

- ^ McDonald & Sanders 2002, Introduction, p. 13. "We should be clear, however, that the current use of the term "canon" to refer to a collection of scripture books was introduced by David Ruhnken in 1768 in his Historia critica oratorum graecorum for lists of sacred scriptures. While it is tempting to think that such usage has its origins in antiquity in reference to a closed collection of scriptures, such is not the case." The technical discussion includes Athanasius's use of "kanonizomenon=canonized" and Eusebius's use of kanon and "endiathekous biblous=encovenanted books" and the Mishnaic term Sefarim Hizonim (external books).

- ^ Athanasius. Letter 39.6.3. "Let no man add to these, neither let him take ought from these."

- ^ Ulrich (2002), pp. 30, 32–33. "But it is necessary to keep in mind Bruce Metzger's distinction between "a collection of authoritative books" and "an authoritative collection of books."

- ^ a b Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments (7 May 2001). "Liturgiam Authenticam" (in Latin and English). Vatican City. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

Canon 24. 'Furthermore, it is not permissible that the translations be produced from other translations already made into other languages; rather, the new translations must be made directly from the original texts, namely ... the Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, as the case may be, as regards the texts of Sacred Scripture.'

- ^ For the number of books of the Hebrew Bible see: Darshan, G. (2012). "The Twenty-Four Books of the Hebrew Bible and Alexandrian Scribal Methods". In Niehoff, M. R. (ed.). Homer and the Bible in the Eyes of Ancient Interpreters: Between Literary and Religious Concerns. Leiden: Brill. pp. 221–44.

- ^ McDonald & Sanders (2002), p. 4.

- ^ W. M., Christie (1925). "The Jamnia Period in Jewish History" (PDF). Journal of Theological Studies. os–XXVI (104): 347–64. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXVI.104.347.

- ^ Lewis, Jack P. (April 1964). "What Do We Mean by Jabneh?". Journal of Bible and Religion. Oxford University Press. 32 (2): 125–32. JSTOR 1460205.

- ^ Freedman, David Noel, ed. (1992). Anchor Bible Dictionary, Vol. III. New York: Doubleday. pp. 634–37.

- ^ Lewis, Jack P. (2002). "Jamnia Revisited". In McDonald, L. M.; Sanders, J. A. (eds.). The Canon Debate. Hendrickson Publishers.

- ^ McDonald & Sanders (2002), p. 5.

- ^ Cited are Neusner's Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine, pp. 128–45, and Midrash in Context: Exegesis in Formative Judaism, pp. 1–22.

- ^ Brettler, Marc Zvi (2005). How To Read The Bible. Jewish Publication Society. pp. 274–75. ISBN 978-0-8276-1001-9.

- ^ Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2002). "The Formation of the Hebrew Canon: Isaiah as a Test Case". In McDonald, L. M.; Sanders, J. A. (eds.). The Canon Debate. Hendrickson Publishers. p. 60.

- ^ Davies, Philip R. (2002). "The Jewish Scriptural Canon in Cultural Perspective". In McDonald, L. M.; Sanders, J. A. (eds.). The Canon Debate. Hendrickson Publishers. p. 50.

With many other scholars, I conclude that the fixing of a canonical list was almost certainly the achievement of the Hasmonean dynasty.

- ^ a b "Samaritans". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com. 1906.